The Background

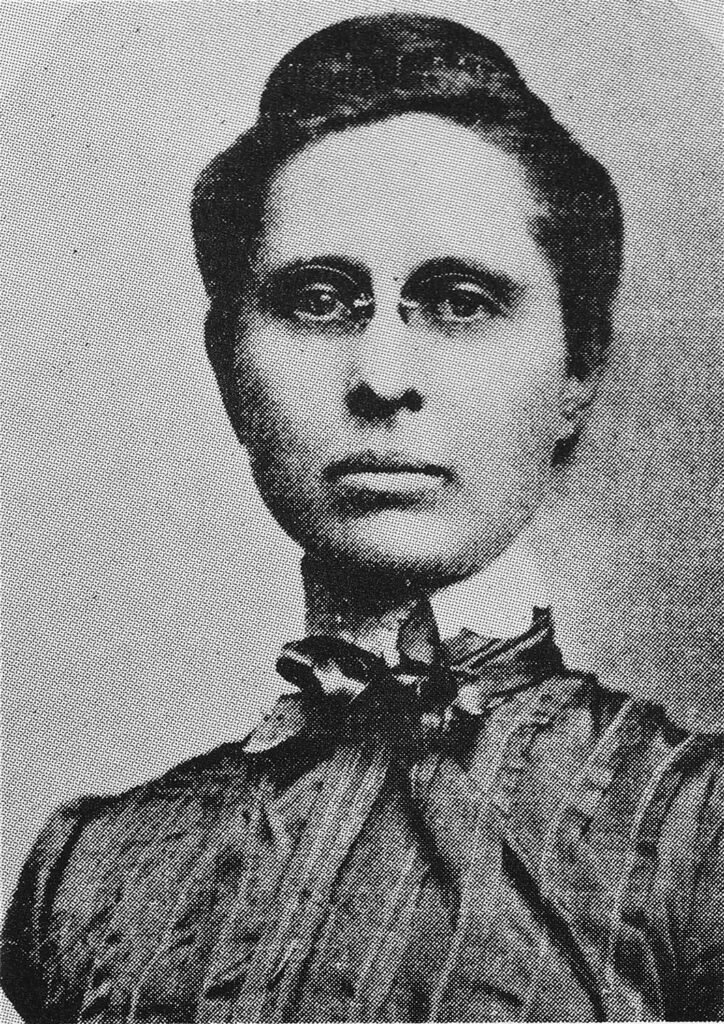

Henrietta Cuttino Dozier (1872-1947), professionally known as Henrietta C. Dozier, was the first female architect in the Southeastern United States, practicing in Atlanta from 1901 to 1914, and then in Jacksonville, Florida, for the remainder of her life and career.

The United States had 22 female architects by 1895,2 which increased to over 200 by 1920.3 Beginning in the 1890s, the slow but steady rise of women in male-dominated professions, including architecture, spurred a flurry of press articles, with claims of a “woman invasion” stoking fierce public reaction — keep in mind, women weren’t even allowed to vote until 1920.

Atlantans’ first exposure to a “lady architect” came during the development of the Cotton States and International Exposition in 1894, when plans for the Women’s Building were solicited exclusively from female designers — a radical proposal at the time.

Upon seeing the submitted plans, T. H. Morgan of Bruce & Morgan reportedly remarked: “Why, these buildings are bold enough to have been drawn by men.”4

Elise Mercur of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, secured the commission for the women’s building, winning over 12 other submissions, including one by Dozier, who was then studying at the Pratt Institute in New York.5 6 Dozier entered Pratt as its only female student, ranking second in her class.7

Dozier (pictured here8) was born in Fernandina Beach, Florida, but raised in Atlanta by her single mother — her father died 4 months before she was born.9 She attended the Atlanta public schools before heading north, where she studied at Pratt and later the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), graduating in 1899 with a B.S. in Architecture10 — one of just three women in a class of 176 students.11

An unconventional woman for her era, Dozier never married, reportedly dressed in men’s clothing, and was known to her friends and family as “Harry” and “Uncle Harry”12 13 14 — draw your own conclusions.

In 1893, The Atlanta Journal described “Harry Dozier” as “a young girl of unusual force and mental determination. She is quite young, and quite handsome…”15

Dozier learned to fly airplanes in her 60s,16 and following her death, her relatives were surprised to discover a manuscript she had written for an unpublished romance novella. Sample text:

“Men do not get what they deserve in life, they get what they go after,” said Elizabeth. “So? My dear, I think women do a lot of going after what they want also … At least, you know how to get what you want.”17

Only one of Dozier’s known works survives in Atlanta: a residence she designed for Mrs. O.K. Slifer on 10th Avenue overlooking Piedmont Park. The structure now serves as a school building and has been altered.

Although Dozier often downplayed her professional difficulties in interviews, there is ample evidence that she faced severe discrimination in a field that largely remains an old boys’ club. As one article noted in 1903: “It is only recently that the men in the profession began to regard women architects as other than a huge joke.”20

Dozier wasn’t a spectacular designer by any means, but she also wasn’t given nearly as many opportunities to refine her skills as her male counterparts, securing few large-scale commissions throughout her career. In a 1939 interview, she noted: “…in the last few years, I have done nothing but small residential homes.”

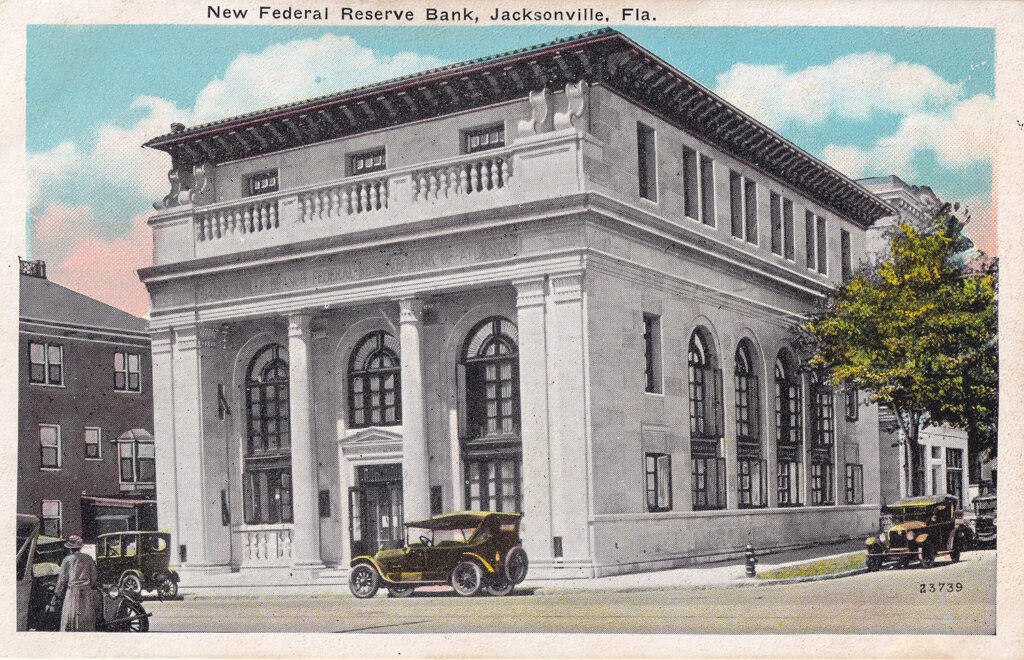

Dozier said she was “always very proud” of her work on the Jacksonville branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta,21 which can easily be considered her finest effort. She was officially credited as supervising architect for the project, working under A. Ten Eyck Brown of Atlanta. However, Brown often claimed credit for projects he had little to no hand in designing, and it appears Dozier did most of the work.

In 1905, Dozier was elected an Associate of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), only the third woman to be accepted into the organization.23 Dozier’s election directly led to the establishment of the Atlanta chapter of the AIA,24 which later became AIA Georgia.

As T.H. Morgan recounted, a minimum of five AIA associates were required to form an AIA chapter, and Dozier, along with Harry Leslie Walker, became the fifth and sixth architects in the city elected as associates, prompting the chapter’s organization.25

During her life, Dozier’s work was barely acknowledged by the press — in either Atlanta or Jacksonville. The handful of news stories written about her often conveyed a tone of curious skepticism, if not outright ridicule.

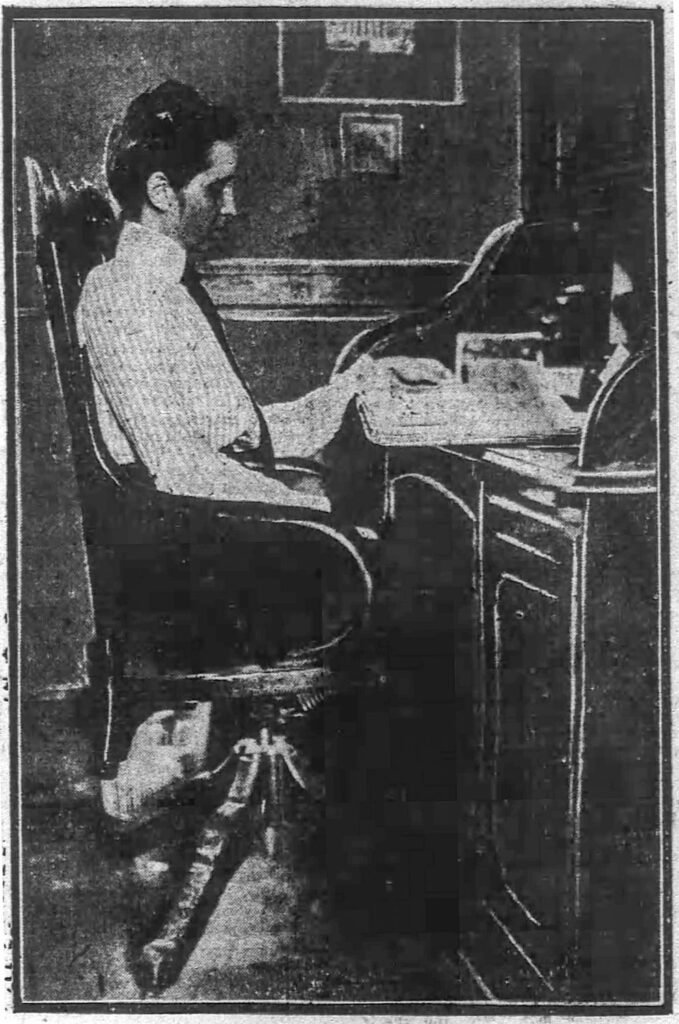

The following article, published in The Atlanta Constitution in 1902, is the first of just a few that were written about Dozier during her time in Atlanta, and it’s as sexist and condescending as it gets.

Dozier had been in practice less than 2 years, and the reporter (obviously male) depicted her interest in architecture as some girlish lark before settling into marriage, claiming that she “makes plans for a future fair with promise, where she may realize a woman’s dreams of ease and mental and domestic pleasure, surrounded by the friends she loves—nature and children and dumb things.”

Maybe that’s what Dozier told the reporter to keep him happy, but she clearly had other ideas for herself.

This Georgia Woman Stands High in Profession of Architecture

“Of all the branches of work into which women are entering there is none which shows so small a percentage of the really successful as that of architecture, and this is particularly true in the south. Two reasons deter the young woman casting about for something upon which to settle. In the first place, it is hard work; in the second, there is the probability of marriage—the state few on the sunny side of twenty-five or thirty could be brought to regard as anything but the ultima thule to which woman existence tends. And when one there is who from choice enters seriously upon a real profession the world might as well see at once, what sooner or later it will have to see, that she will succeed.

When Miss Henrietta C. Dozier entered as apprentice in an architect’s office she set herself to work as a man does—not simply to bridge over a year or two until the time when she would marry—she began at the beginning and held on to the finish. A year of apprenticeship was followed by two at Pratt Institute; then after some months in New York she went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, remaining four years. Coming south, she opened an office in Jacksonville, Fla., where she was in business six months, but in compliance with solicitations from friends in Atlanta decided to remove to this place, where she is permanently located and established, doing business with a man’s understanding and knowledge and a woman’s thoroughness and regard for detail.

Architecture is peculiarly suited to woman from the fact that her ideas on the requirements of a house are more practical than those of a man. Too, if she has first an all-round knowledge of mechanics her artistic instinct will serve her well. Miss Dozier, realizing what a woman wants and knowing how to go about having it, has built her own house—a unique and picturesque cottage, modern and complete, and meeting her needs as nobody else could have planned for her.

Here, in her hours of recreation, she enjoys with her mother and sister the sweetness of home, and makes plans for a future fair with promise, where she may realize a woman’s dreams of ease and mental and domestic pleasure, surrounded by the friends she loves—nature and children and dumb things.

Miss Dozier, like Dorothy Manners, has “the generations” back of her. Her forbear, Thomas Smith, of South Carolina, was landgrave in 1663, or there abouts, and a long line of ancestors have bequeathed to this young woman the intrepid spirit which no mere circumstance can daunt, and placed in her slender hand the key which unlocks every door—a will that brooks no thwarting.

As an architect she is a success; she has mastered her profession and she makes it pay.26

References

- Wells, John E. and Dalton, Robert E. The South Carolina Architects, 1885-1935: A Biographical Dictionary. Richmond, Virginia: New South Architectural Press (1992), p. 42. ↩︎

- “Uncle Sam And The New Woman.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 30, 1895, p. 32. ↩︎

- Allaback, Sarah. The First Women Architects. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press (2008), p. 2. ↩︎

- “Current Events From A Woman’s Point Of View.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 2, 1894, p. 6. ↩︎

- “Plans By Fair Hands”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 28, 1894, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Tiffany Will Be Here.” The Atlanta Journal, November 28, 1894, p. 6. ↩︎

- “Society”. The Atlanta Journal, March 18, 1893, p. 2. ↩︎

- Photo credit: Wood, Wayne W. Jacksonville’s Architectural Heritage: Landmarks for the Future. Jacksonville, Florida: University of North Florida Press (1989), p. 9. ↩︎

- Spotlight: Henrietta Dozier – Jacksonville History Center ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Atlanta Girl Is Lionized.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 8, 1899, p. ↩︎

- “Society”. The Atlanta Journal, March 18, 1893, p. 2. ↩︎

- Parks, Cynthia. “‘Cousin Harry’ Practiced What She Built”. The Florida Times-Union (Jacksonville, Florida), July 18, 1976, p. G-2. ↩︎

- Weightman, Sharon. “They called her Harry”. The Florida Times-Union (Jacksonville, Florida), July 10, 1994. p. D-4. ↩︎

- “Society”. The Atlanta Journal, March 18, 1893, p. 2. ↩︎

- ↩︎

- Weightman, Sharon. “They called her Harry”. The Florida Times-Union (Jacksonville, Florida), July 10, 1994. p. D-4. ↩︎

- “The Real Estate Field”. The Atlanta Journal, October 31, 1911, p. 19. ↩︎

- “Some Personal Mention”. The Atlanta Journal, January 28, 1912, p. L5. ↩︎

- Chapman, Josephine Wright. “Do Women Architects Underchage?” The Atlanta Journal, November 14, 1903, p. 15. ↩︎

- Spotlight: Henrietta Dozier – Jacksonville History Center ↩︎

- “New Federal Reserve Bank Home”. The Sunday Times-Union (Jacksonville, Florida), June 1, 1924, p. 19. ↩︎

- Weightman, Sharon. “They called her Harry”. The Florida Times-Union (Jacksonville, Florida), July 10, 1994. p. D-4. ↩︎

- Morgan, Thomas H. “The Georgia Chapter of The American Institute of Architects”. The Atlanta Historical Bulletin, Volume 7, No. 28 (September 1943): pp. 89-90. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “This Georgia Woman Stands High In Profession of Architecture”. The Atlanta Constitution, October 12, 1902, p. 6. ↩︎