The Background

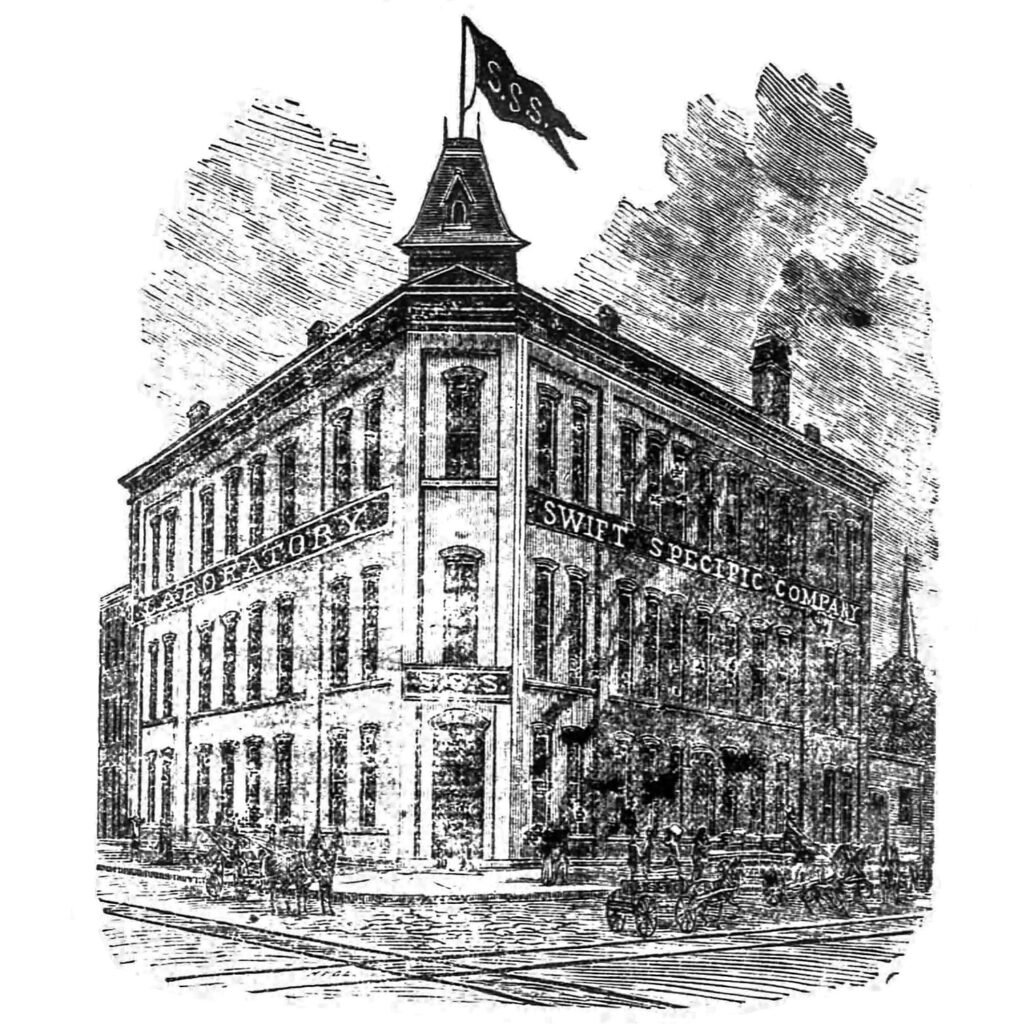

The following article was published in The Atlanta Constitution in 1883, and despite its title — “New Atlanta Buildings” — the article discusses a single structure: the laboratory of the Swift Specific Company, designed by E.G. Lind (1829-1909).

Blurring the line between news and advertisement, the article essentially served as a promotion for the Atlanta-based manufacturer of the “S.S.S.” tonic, a cure-all elixir sold across the United States and Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The company still exists, and the product is still manufactured in Atlanta, so I won’t be too disparaging. Suffice it to say, when an unregulated medicinal tonic is billed as the “Great Blood Remedy of the Age,” claiming to cure everything from sores, ulcers, and boils to eczema, rheumatism, blood diseases,2 and — oh, yes — syphilis,3 there’s room to be skeptical.

Typical of Atlanta, the tonic also has a shady and convoluted backstory. The recipe for the remedy was reportedly offered by members of the Muscogee Nation to Irwin Dennard of Perry, Georgia, in 1826. Dennard later sold the formula to Charles T. Swift, who formed a company to manufacture the product, relocating it to Atlanta in 1873.4

Humphries & Norrman were initially reported as the designers of the company’s factory in 1883,5 but all evidence indicates E.G. Lind designed the completed building. Lind’s own project list includes the factory,6 and one of the company’s directors was J.W. Rankin, a repeat client of Lind’s, and a member of the building committee for Atlanta’s Central Presbyterian Church, which Lind also designed.7

Lind’s records indicate that the project cost was $12,000,8 but the company claimed it totaled over $30,000 with machinery.9

Location of Swift Specific Company

The 3-story brick factory was built on the northeast corner of Hunter and South Butler Streets (later Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive SE and Jesse Hill, Jr. Drive SE), bordering the Georgia Railroad.

Then located on the edge of the city, the site was surrounded by a low-rent district of shanties and small factories, but was also two blocks from the central freight depot — ideal for distribution.

In advertisements from the 1880s and 1890s, the company often touted its proximity to the Georgia State Capitol, located one block west of the factory. The Fulton County Jail was later built next door to the facility, but they never mentioned that in their marketing.

Considering the company’s constant promotion in the Atlanta press, it’s surprisingly difficult to find any articles that discuss the development of its property after 1883.

At some point between 1899 and 1911, the factory appears to have doubled in size.10 11 My best guess is that the expansion took place circa 1902, after the company bought an adjoining lot on Hunter Street in 1901.12 Who the designer of the addition was is unclear — Lind left Atlanta in 1893 and retired from practice.

Later renamed the S.S.S. Company, the factory continued operating at the same location until circa 1956-57, when the entire area was acquired and cleared for the construction of the I-75/85 Downtown Connector.13 14 The site is now occupied by an exit ramp.

“New Buildings In Atlanta.”

New Laboratory Of The Swift Specific Co.

Now being erected corner Hunter and Butler streets, one block below the City Hall, one hundred feet long, eighty feet

wide–three stories and cellar.

We give a drawing of the new Laboratory of The Swift Specific Company now being built corner Hunter and Butler streets. This will be a handsome building, an ornament to that part of the city, and is not only an evidence of the thrift and growth of Atlanta, but is a most substantial proof the confidence of the proprietors of this extraordinary remedy in its merit, and the permanent business of its manufacture and sale. In fact, they know so well that their remedy is all they claim for it, they have no hesitation in investing twenty to forty thousand dollars in substantial buildings and improved machinery for its manufacture. They will have in their new Laboratory at [sic] 30-horse power engine, two boilers, ten immense steam tight percolators, a large mill for grinding the roots, a powerful press of two tons to the inch for extracting the juices, besides numerous bottle washing and bottle filling machines. Taken as a whole, it will be, when finished, one of the most complete Laboratories in America, and will be superintended by a practical Pharmacist and Chemist of 25 years experience.

Since Swift’s Specific has come into general use as a health tonic, the demand has increased so rapidly and largely that the Company have had difficulty in keeping up the supply, but now they expect to be prepared for all emergencies, as their capacity will be, after October 1st, over a million dollars a year.

Letters From the People.

A Marvelous Cure.

From the Memphis Appeal, August 1.

To the Editors of the Appeal: Noticing in your paper where S.S.S. had effected a cure in an aggravated case of scrofula, I have concluded to give My experience with the remedy mentioned. Some time ago I was afflicted with a very stubborn case of eczema; at the time I was living in Philadelphia. It got worse and worse, until my face and other portions of my body were covered with a mass of running sores. I visited my family physician, and after being under his care for a long time without any relief he turned me over to Prof. Duffing, a noted expert on skin diseases, and after swallowing a barrel of medicine prescribed by him without giving me any relief, I consulted with several other professional experts with a like success. I was miserable, and despaired of a cure. Being very skeptical in regard to the effect of patent medicines, I had as yet not tried any, but being advised by many people I commenced at the top of the list of patient remedies for eczema, ectyma, mentagra and other skin affectations, and I think I tried them all, still however, without doing me any good. I had heard of S.S.S., and although I had been repeatedly advised by my friends to try it, still as each remedy failed in producing the desired result, and as with each failure my skepticism increased, I refused to take it until in utter desperation I concluded to give it a trial as a last resort, not believing, however, it would have a beneficial effect. But to my surprise, after taking several bottles, I noticed a decided improvement, and when I had finished the fifth bottle I shouted hurrah, for my skin was without a blemish, as fair and smooth as possible. I write this in the interest of anyone that may be afflicted likewise, and now I swear by S.S.S.

DRUMMER.

P.S.–I would be pleased to correspond with anyone that is interested, and give them full details.

Address “DRUMMER,”

Care Memphis Appeal15

References

- Photo credit: Atlanta in 1890: “The Gate City”. Atlanta: The Atlanta Historical Society, Inc. (1986), p. 35. ↩︎

- “Swift’s Specific” (advertisement). The Atlanta Constitution, February 18, 1883, p. 10. ↩︎

- “Important Reduction In Price Of Swift’s S. Specific” (advertisement). The Atlanta Constitution, October 23, 1891, p. 6. ↩︎

- Company Leadership Over the Years – S.S.S. Company ↩︎

- “How We Grow.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 10, 1883, p. 3. ↩︎

- Belfoure, Charles. Edmund G. Lind: Anglo-American Architect of Baltimore and the South. Baltimore, Maryland: The Baltimore Architectural Foundation (2009), p. 180. ↩︎

- Belfoure, p. 144. ↩︎

- Belfoure, p. 180. ↩︎

- Company advertisement. The Atlanta Constitution, December 16, 1883, p. 4. ↩︎

- Insurance maps of Atlanta, Georgia, 1899 / published by the Sanborn-Perris Map Co. Limited ↩︎

- Insurance maps, Atlanta, Georgia, 1911 / published by the Sanborn Map Company ↩︎

- “Property Transfers.” The Atlanta Journal, September 9, 1901, p. 5. ↩︎

- Hamilton, Joe. “Big Change Coming In Street Network”. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, June 10, 1956, p. 1-C. ↩︎

- “Work Begins on Connector Link Sewer Project”. The Atlanta Journal, January 10, 1957, p. 25. ↩︎

- “New Buildings In Atlanta.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 5, 1883, p. 11. ↩︎