The Background

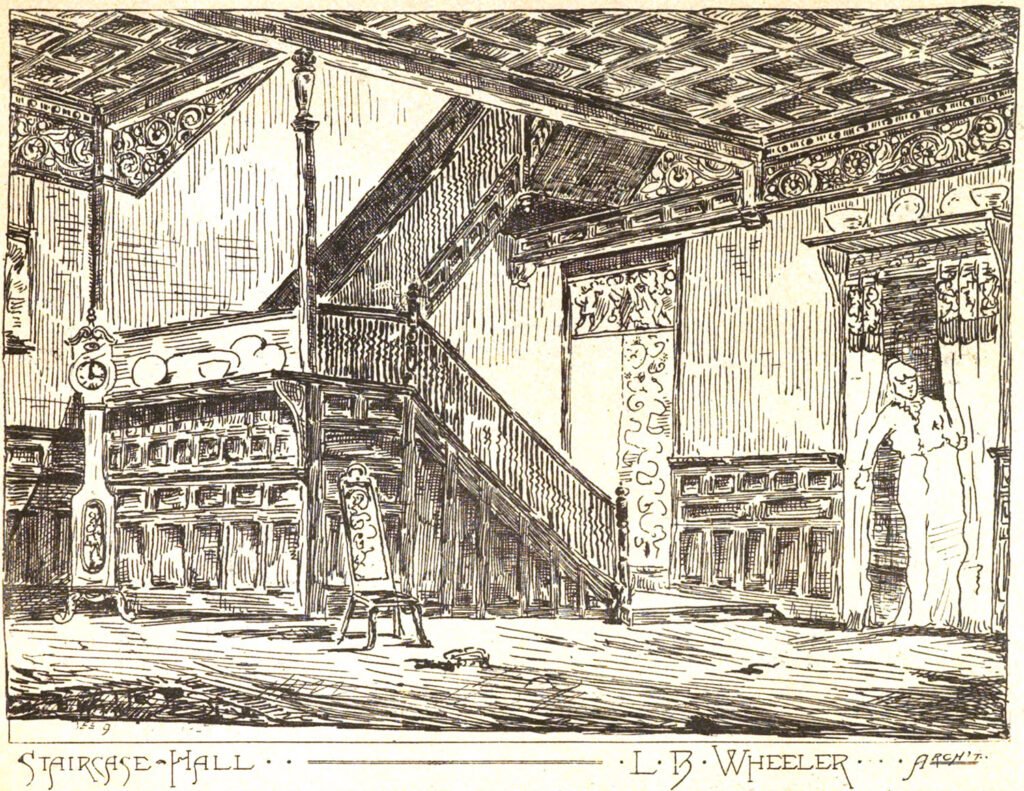

This is the third in a series of 5 articles on home decoration written by L.B. Wheeler (1854-1899), an architect who practiced in Atlanta from 1883 to 1891. The articles were published in The Atlanta Constitution in December 1885 and January 1886.

Here, Wheeler spoke in harsh terms of fickle fashionistas who fretted over building their homes in the latest style, imploring his readers to consider “the length of the period for which we expect to build, which shall, in all probability, be for the remainder of our lives”.

That advice would have fallen on deaf ears in 1880s Atlanta, where the nouveau riche changed houses like their soggy underwear (from the humidity, of course), hopping from one new residence to the next every few years, each one inevitably more overwrought and gaudy than the last.

Atlanta has always been a parade of bullshit and spectacle, and Wheeler could have only had the houses of Peachtree Street in mind when he spoke of “a museum in which we store all sorts of unnatural curiosities and uninteresting bric-a-brac…overloaded with superficial ornaments in strained and unnatural attitudes, posed with a smirk before the audience like a ballet dancer awaiting applause.”

Wheeler mourned for the “lack of character, simplicity, refinement…” and other timeless attributes missing in late 19th-century architecture, a sentiment echoed by other Atlanta architects of the era — notably, G.L. Norrman, who later shared his own acerbic remarks about the city’s homes, although Wheeler was even more caustic here.

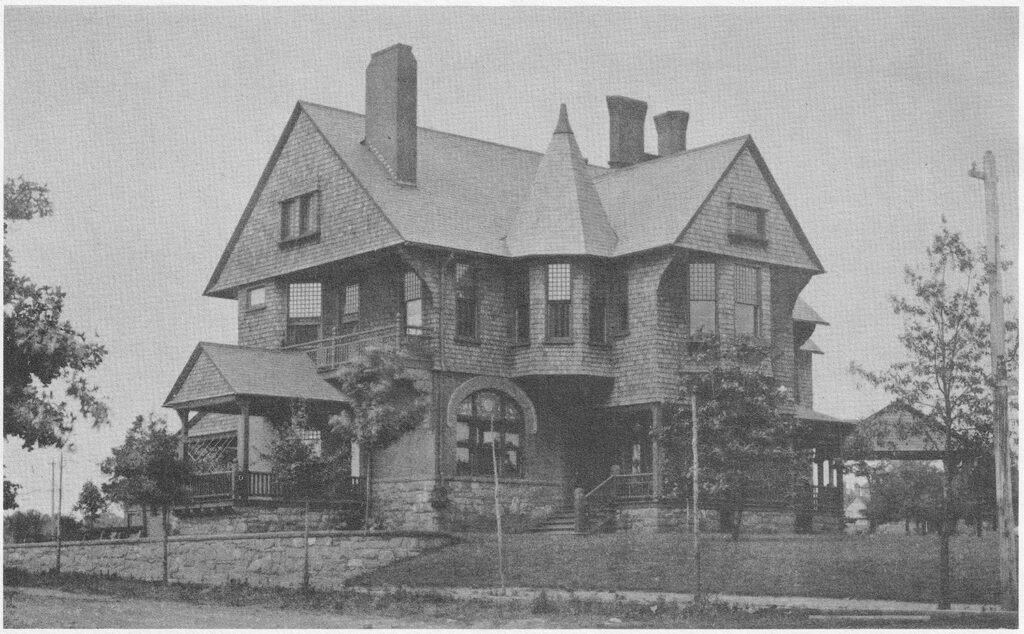

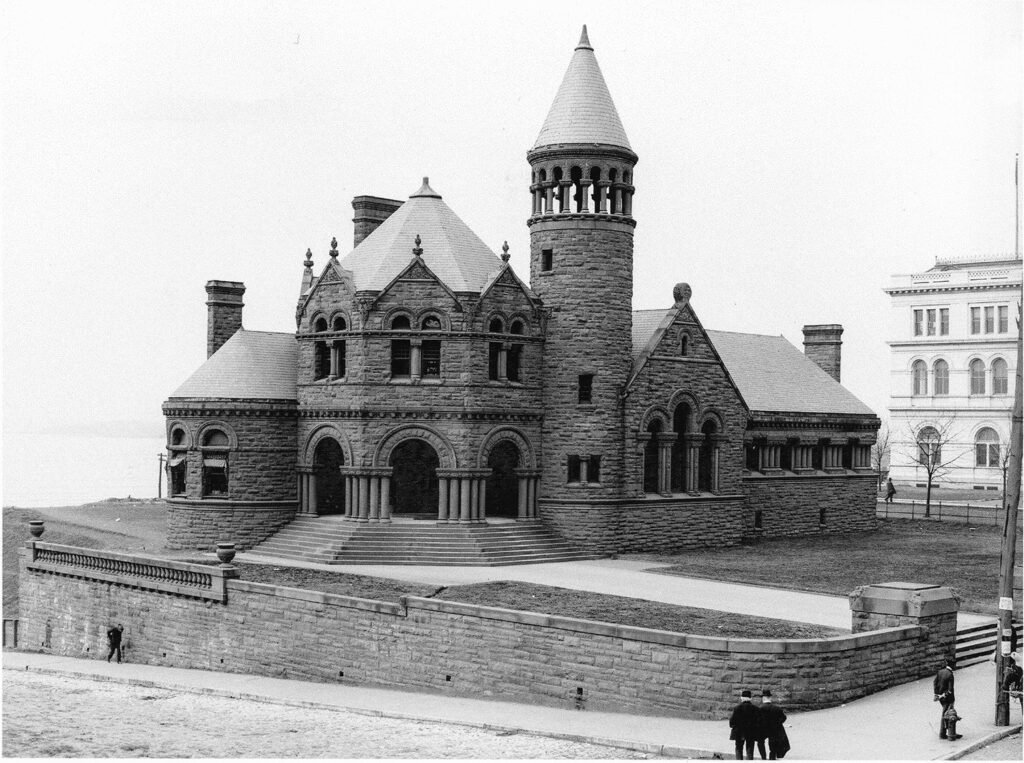

The irony is that Wheeler proved himself quite willing to satiate the whims of Atlanta’s elite. Photographic evidence abounds of the many ostentatious residences of his design, a legacy continued by his protege, W.T. Downing, who spent years littering the city with garish mansions, most of them mercifully destroyed in the 20th century.

It was as true then as it is today: If you have to be wealthy, for God’s sake, develop a little taste to relieve us of your affliction.

Style and Fashion

By L.B. Wheeler, Architect of the New H.L. Kimball House.

December 27, 1885

The prevailing style of architecture and the probable length of its fashionable existence, is to those contemplating the building of a home, often a question of serious disturbance. If we will think for a moment of the length of the period for which we expect to build, which shall, in all probability, be for the remainder of our lives, it would seem that the folly of following the dictation of an unreasoning fashion, which is constantly changing, would be apparent. If you are sure the style of your house is sanctioned by judgment and reason, you need have no fear in violating fashion’s decrees.

There is a prevailing impression that an architectural style consists of a set of forms–a sort of architectural clothing–to be used as fancy dictates. But the forms of a style, apart from its principles, which are its soul and life, are no more a style than the wooden image in front of a cigar store is a man. Taste, climate, materials, social conditions, wealth and various other circumstances, have given rise, in different countries and at different periods of time, to certain methods and principles of design, the application of which, in the erection of the monuments and buildings of those countries and periods have created certain architectural forms, which have been systematized and called styles. The frequency with which we see buildings dressed in these various styles without any regard to applicability, scattered along our thoroughfares like a great international masquerade, in which, by the way, some of the costumes are very curious, shows there must either be very great differences in the climate, social conditions and the nature and duties of materials on adjoining lots, or else there is a lamentable state of education in regard to the fitness of things.

Have you ever realized the possibilities of beauty to which our modern streets are susceptible? The great picture galleries that might be made of them! What charming pictures of social and domestic life could be arranged along their sides!

In the pictures of the artist the hills and foliage, the green meadows and even the sky are of paint: in ours they may be living, breathing realities possessing thousands of beauties inimitable. With such materials, what ought we not to accomplish, and what have we done?

Instead of making of our cities living pictures, expressing refinement, purity and nobility, we make of them a museum in which we store all sorts of unnatural curiosities and uninteresting bric-a-brac. The great faults of our modern architecture are lack of character, simplicity, refinement, delicacy, tenderness, beauty, grandeur, picturesqueness, homeliness, and sentiments, the expression of some one of which has been the endeavor of every good work erected by man. The designer’s highest purpose seems to be the representation of prettiness, novelty, and the demonstration of wealth, and even in this he fails–without any perception of the laws governing composition of the artistic susceptibilities of the materials used. His attempts to impart prettiness result in fantastic buildings, overloaded with superficial ornaments in strained and unnatural attitudes, posed with a smirk before the audience like a ballet dancer awaiting applause. Novelty which could formerly have been obtained by designing something more absurd than ever had been done before, would have been quite in his line and easy of accomplishment. If the field had not been so well filled by his contemporaries, that now a thing to be novel must necessarily be good–something quite beyond his powers. To demonstrate the possession of wealth he loads his building with starring ornaments, breaks everything up and fills every blank space with an inappropriate ornament. His universal recipe for producing repose, breadth and refinement in his composition, attaches his building to a tower of much grandeur, and no use whatever, and completes a building which, if it were not too large, would make a very good toy savings bank–a nice one with a tower handle. The exterior of a building should be the simple and natural clothing of the interior, and should express its character and purpose above all things. Truth is essential and means the correspondence of the representation with the facts. There should be no shams about the building. Nothing is as vulgar as the imitation by a cheap material of one more valuable. It deceives no one and creates on discovery an impression similar to that produced by the use of paste diamonds and bogus jewelry. The humblest materials used honestly, in positions suited to their functions, may be made beautiful, and in certain places their services are indispensable. It is by the arrangement of the materials and not their value that a house is made attractive. You might build a house of gold with diamond windows which would be very ugly and perfectly useless.

There should be no unnecessary towers, dormers, gables, windows, or other features which, by their presence, imply that they are there for a practical purpose which they do not fulfill. Features used in this way are not ornaments; they are architectural lies. What would you think of a man who covered himself with glass eyes and wax roses to make himself beautiful? They would not be more ridiculous than are some of the excrescences which are put upon many of our buildings and not unlike them in effect. Some people are blind to beauty, as others are to color. It is a defect in their natures like the want of a musical ear. These with many others who from fear of criticism, thoughtlessness, indolence, ignorance, and a meek desire to follow, however distantly, in the footsteps of wealth, are guided in matters of taste almost exclusively by the dictates of fashion; and even in their devotion to so sordid a government they are often imposed upon, receiving some very bitter doses, sweetened with a few of the detail of a prevailing style which, to their unsophisticated palate, has the flavor of the genuine article. If the motives in which fashion has its origin and the sources from which it springs were thoroughly understood it would have numerous less worshipers than now. Nature’s fashions never change. The leaves of the trees come in spring with the summer winds and gay troops of young flowers and in the autumn put on their gorgeous mourning as they have ever done. It would puzzle the oldest inhabitant to remember a change in the fashion of man, still our fashions are changing constantly. It must be either because there is no beauty in them or we fail to discover or appreciate it. We should learn to understand beautiful things and love them for their inherent beauties and not bondage our likes and dislikes to popular fancy. There would be no objections to the edicts of fashion if they were good and right; but the fact that a thing to be fashionable must be sanctioned by the majority is when we think that on matters requiring special knowledge, the majority are never right, almost enough to condemn it without further evidence. Fashion is a common bait thrown by the tradesmen to allure the wary dollars from our pockets. What could be expected from such a motive? A high standard of merit endeavoring to elevate and purify the public taste? No. The fisher with such a bait would go hungry for dollars. He must throw something more palatable to the multitude. So he fits up something nice, new and bright, calls it the latest style and fills his basket with dollars. This latest style is a very popular bait. The later it is the better. “There are no old masters now.” In this advertising age of ours every lecture-play-musical composition and every product of the manufacturer is an improvement upon its predecessor, and he who waits for perfection “is like the rustic who waited for the river to run by.”5

References

- “Eight Millions More.” The Atlanta Constitution, April 13, 1890, p. 7. ↩︎

- “A Handsome Residence”. The Atlanta Constitution, April 19, 1890, p. 4. ↩︎

- Furniss, Jim. “New York Firm Plans Store Here”. The Atlanta Constitution, August 21, 1946, p. 1. ↩︎

- Atlanta Homes: Attractiveness of Residences in the South’s Chief City. Atlanta: Atlanta Presbyterian Publishing Company. ↩︎

- Wheeler, L.B. “Style and Fashion.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 27, 1885, p. 4. ↩︎