Category: Architects of Atlanta and the Southeast

-

Swift Specific Company – Atlanta (1883-1956)

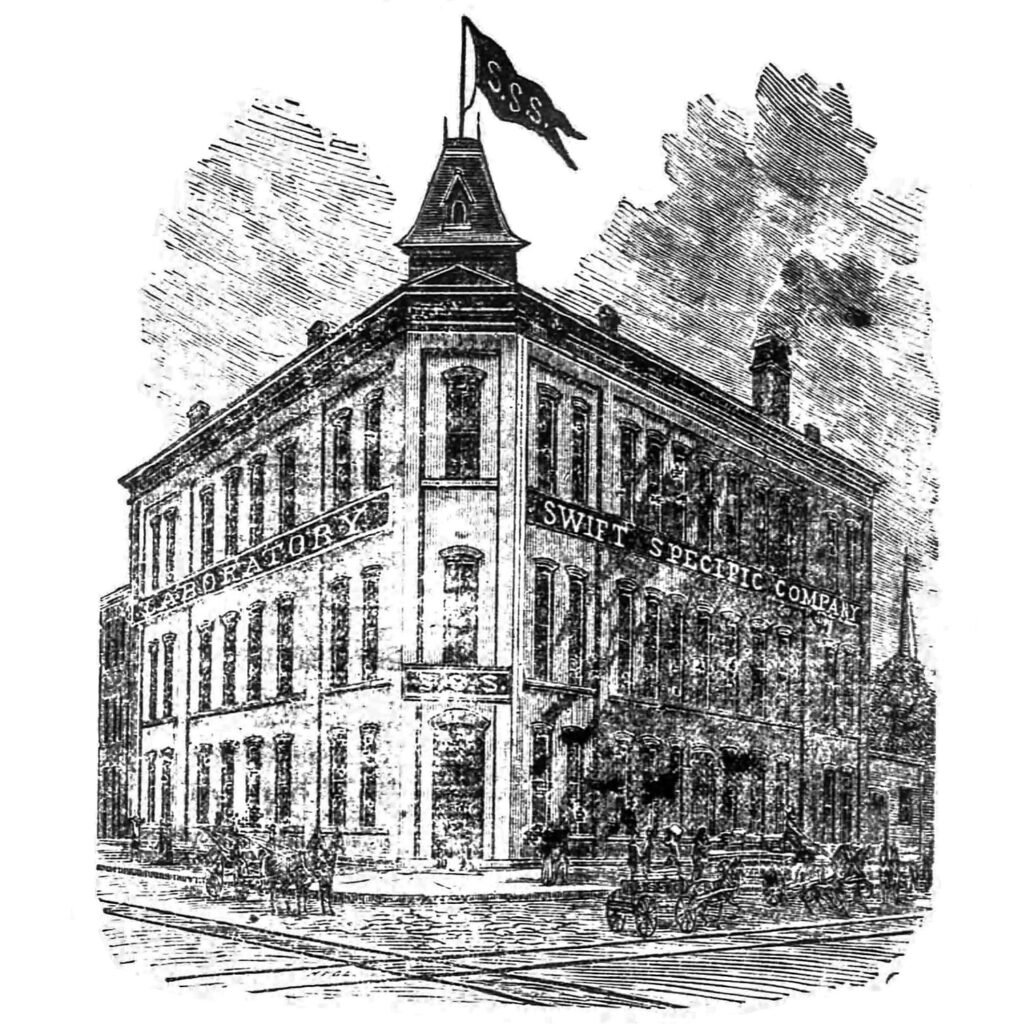

Edmund G. Lind. Swift Specific Company (1883-1956). Atlanta.1 The Background

The following article was published in The Atlanta Constitution in 1883, and despite its title — “New Atlanta Buildings” — the article discusses a single structure: the laboratory of the Swift Specific Company, designed by E.G. Lind (1829-1909).

Blurring the line between news and advertisement, the article essentially served as a promotion for the Atlanta-based manufacturer of the “S.S.S.” tonic, a cure-all elixir sold across the United States and Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The company still exists, and the product is still manufactured in Atlanta, so I won’t be too disparaging. Suffice it to say, when an unregulated medicinal tonic is billed as the “Great Blood Remedy of the Age,” claiming to cure everything from sores, ulcers, and boils to eczema, rheumatism, blood diseases,2 and — oh, yes — syphilis,3 there’s room to be skeptical.

Typical of Atlanta, the tonic also has a shady and convoluted backstory. The recipe for the remedy was reportedly offered by members of the Muscogee Nation to Irwin Dennard of Perry, Georgia, in 1826. Dennard later sold the formula to Charles T. Swift, who formed a company to manufacture the product, relocating it to Atlanta in 1873.4

Humphries & Norrman were initially reported as the designers of the company’s factory in 1883,5 but all evidence indicates E.G. Lind designed the completed building. Lind’s own project list includes the factory,6 and one of the company’s directors was J.W. Rankin, a repeat client of Lind’s, and a member of the building committee for Atlanta’s Central Presbyterian Church, which Lind also designed.7

Lind’s records indicate that the project cost was $12,000,8 but the company claimed it totaled over $30,000 with machinery.9

Location of Swift Specific Company

The 3-story brick factory was built on the northeast corner of Hunter and South Butler Streets (later Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive SE and Jesse Hill, Jr. Drive SE), bordering the Georgia Railroad.

Then located on the edge of the city, the site was surrounded by a low-rent district of shanties and small factories, but was also two blocks from the central freight depot — ideal for distribution.

In advertisements from the 1880s and 1890s, the company often touted its proximity to the Georgia State Capitol, located one block west of the factory. The Fulton County Jail was later built next door to the facility, but they never mentioned that in their marketing.

Considering the company’s constant promotion in the Atlanta press, it’s surprisingly difficult to find any articles that discuss the development of its property after 1883.

At some point between 1899 and 1911, the factory appears to have doubled in size.10 11 My best guess is that the expansion took place circa 1902, after the company bought an adjoining lot on Hunter Street in 1901.12 Who the designer of the addition was is unclear — Lind left Atlanta in 1893 and retired from practice.

Later renamed the S.S.S. Company, the factory continued operating at the same location until circa 1956-57, when the entire area was acquired and cleared for the construction of the I-75/85 Downtown Connector.13 14 The site is now occupied by an exit ramp.

“New Buildings In Atlanta.”

New Laboratory Of The Swift Specific Co.

Now being erected corner Hunter and Butler streets, one block below the City Hall, one hundred feet long, eighty feet

wide–three stories and cellar.We give a drawing of the new Laboratory of The Swift Specific Company now being built corner Hunter and Butler streets. This will be a handsome building, an ornament to that part of the city, and is not only an evidence of the thrift and growth of Atlanta, but is a most substantial proof the confidence of the proprietors of this extraordinary remedy in its merit, and the permanent business of its manufacture and sale. In fact, they know so well that their remedy is all they claim for it, they have no hesitation in investing twenty to forty thousand dollars in substantial buildings and improved machinery for its manufacture. They will have in their new Laboratory at [sic] 30-horse power engine, two boilers, ten immense steam tight percolators, a large mill for grinding the roots, a powerful press of two tons to the inch for extracting the juices, besides numerous bottle washing and bottle filling machines. Taken as a whole, it will be, when finished, one of the most complete Laboratories in America, and will be superintended by a practical Pharmacist and Chemist of 25 years experience.

Since Swift’s Specific has come into general use as a health tonic, the demand has increased so rapidly and largely that the Company have had difficulty in keeping up the supply, but now they expect to be prepared for all emergencies, as their capacity will be, after October 1st, over a million dollars a year.

Letters From the People.

A Marvelous Cure.

From the Memphis Appeal, August 1.

To the Editors of the Appeal: Noticing in your paper where S.S.S. had effected a cure in an aggravated case of scrofula, I have concluded to give My experience with the remedy mentioned. Some time ago I was afflicted with a very stubborn case of eczema; at the time I was living in Philadelphia. It got worse and worse, until my face and other portions of my body were covered with a mass of running sores. I visited my family physician, and after being under his care for a long time without any relief he turned me over to Prof. Duffing, a noted expert on skin diseases, and after swallowing a barrel of medicine prescribed by him without giving me any relief, I consulted with several other professional experts with a like success. I was miserable, and despaired of a cure. Being very skeptical in regard to the effect of patent medicines, I had as yet not tried any, but being advised by many people I commenced at the top of the list of patient remedies for eczema, ectyma, mentagra and other skin affectations, and I think I tried them all, still however, without doing me any good. I had heard of S.S.S., and although I had been repeatedly advised by my friends to try it, still as each remedy failed in producing the desired result, and as with each failure my skepticism increased, I refused to take it until in utter desperation I concluded to give it a trial as a last resort, not believing, however, it would have a beneficial effect. But to my surprise, after taking several bottles, I noticed a decided improvement, and when I had finished the fifth bottle I shouted hurrah, for my skin was without a blemish, as fair and smooth as possible. I write this in the interest of anyone that may be afflicted likewise, and now I swear by S.S.S.

DRUMMER.

P.S.–I would be pleased to correspond with anyone that is interested, and give them full details.Address “DRUMMER,”

Care Memphis Appeal15References

- Photo credit: Atlanta in 1890: “The Gate City”. Atlanta: The Atlanta Historical Society, Inc. (1986), p. 35. ↩︎

- “Swift’s Specific” (advertisement). The Atlanta Constitution, February 18, 1883, p. 10. ↩︎

- “Important Reduction In Price Of Swift’s S. Specific” (advertisement). The Atlanta Constitution, October 23, 1891, p. 6. ↩︎

- Company Leadership Over the Years – S.S.S. Company ↩︎

- “How We Grow.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 10, 1883, p. 3. ↩︎

- Belfoure, Charles. Edmund G. Lind: Anglo-American Architect of Baltimore and the South. Baltimore, Maryland: The Baltimore Architectural Foundation (2009), p. 180. ↩︎

- Belfoure, p. 144. ↩︎

- Belfoure, p. 180. ↩︎

- Company advertisement. The Atlanta Constitution, December 16, 1883, p. 4. ↩︎

- Insurance maps of Atlanta, Georgia, 1899 / published by the Sanborn-Perris Map Co. Limited ↩︎

- Insurance maps, Atlanta, Georgia, 1911 / published by the Sanborn Map Company ↩︎

- “Property Transfers.” The Atlanta Journal, September 9, 1901, p. 5. ↩︎

- Hamilton, Joe. “Big Change Coming In Street Network”. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, June 10, 1956, p. 1-C. ↩︎

- “Work Begins on Connector Link Sewer Project”. The Atlanta Journal, January 10, 1957, p. 25. ↩︎

- “New Buildings In Atlanta.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 5, 1883, p. 11. ↩︎

-

“St. Luke’s Cathedral” (1883-1906)

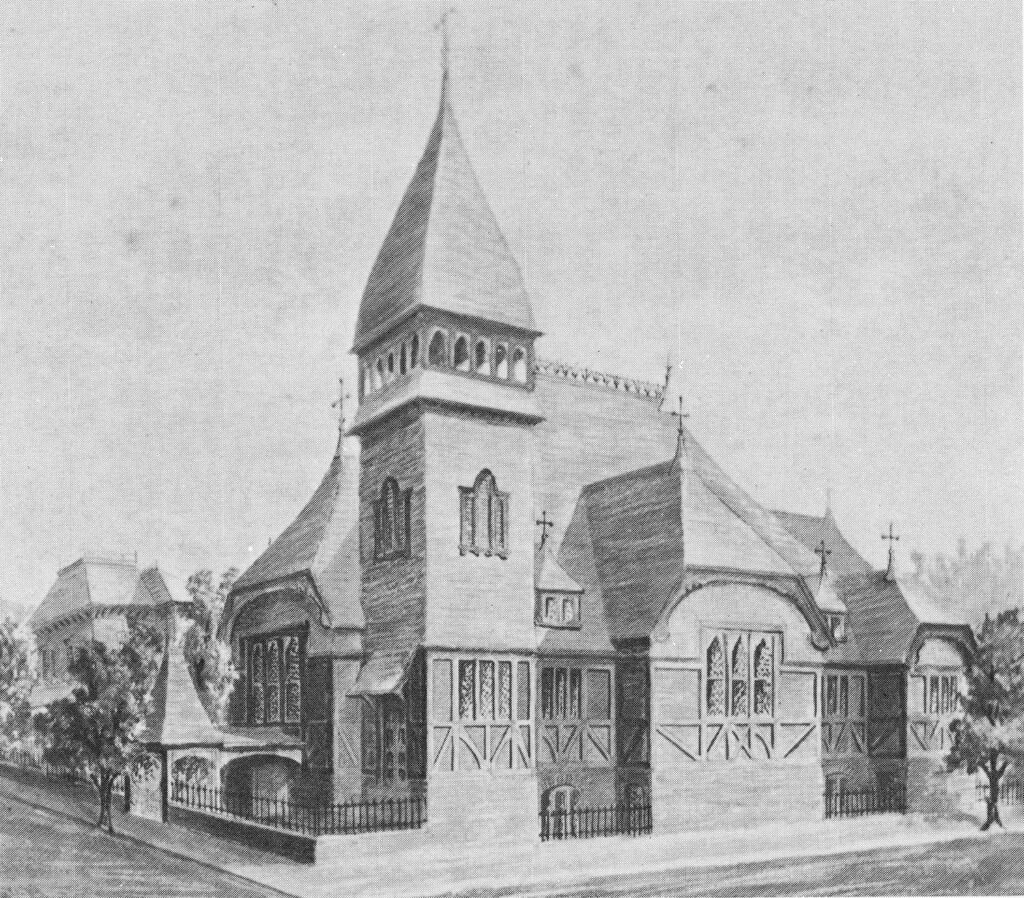

G.L. Norrman. St. Luke’s Cathedral (1883-1906). Atlanta.1 The Background

The following article was published in The Atlanta Constitution in February 1883, and celebrated the completion of one of the first major works by G.L. Norrman (1848-1909) in Atlanta: St. Luke’s Cathedral.

Although the project was credited to the firm of Humphries & Norrman, it appears Norrman was the primary designer — the illustration included with the article is even signed in his handwriting.

St. Luke’s Episcopal Church was founded in 1864, with its first building destroyed by the Union army in the burning of Atlanta.2 The church’s second structure was located at the southeast corner of Spring and Walton Streets,3 but in 1882, the congregation was forced to sell the property after it failed to pay for furnishings from a local store owner, who in turn sued the church and won.4 Pay for your pews, damn it.

Humphries & Norrman began working on plans for a new building in July 1882, although it wasn’t clear if the project would even be executed, as the church also considered moving its old structure to their new property5 at the northeast corner of Houston and Pryor Streets, just off Peachtree Street.

Location of St. Luke’s Cathedral

The plans were ultimately accepted, and construction on the sanctuary was rapid — about 4 months. Building had “begun only a few weeks ago” when the cornerstone was laid on October 21, 1882,6 and the first service was held in the church’s basement on Christmas Day 1882,7 although the interiors were completed in February 1883.

The article below describes the building’s interior in exacting detail, but doesn’t say anything about its exterior, which was clad in brick and topped with a 60-foot-high steeple.8 The final cost of the project was just $5,500.9

When the church was constructed, it was barely within the city limits and towered over the one and two-story homes around it.

Within ten years, Atlanta’s ever-expanding commercial district engulfed the building, and in 1892, when the church lost its cathedral designation to nearby St. Philip’s,10 the St. Luke’s sanctuary was overshadowed by the rise of its new next-door neighbor: DeGive’s Grand Opera House, a 7-story entertainment palace.

One year later, Atlanta’s first “flatiron” structure, the 3-story commercial Peck Building, designed by G.L. Norrman, was erected on a sliver of land across from St. Luke’s entrance, blocking the church’s exposure to Peachtree Street.

In 1906, only twenty-three years after the sanctuary’s completion, St. Luke’s sold out to DeGive,11 and the congregation moved further up Peachtree Street into a new building designed by P. Thornton Marye,12 13 which still stands.

Georgia-Pacific Center (1982), the former site of St. Luke’s Cathedral. Atlanta. The old St. Luke’s was demolished in October 1906, with materials from the structure salvaged to build a home on Gilmer Street,14 also long since destroyed. The former church property was replaced with a block of single-level stores15 and is now the site of the Georgia-Pacific Center in Downtown Atlanta.

After the sanctuary was demolished, “M.S” commented on the church’s move in the “Women and Society” column of The Atlanta Journal:

In olden times if a congregation wished to build a new church and leave the old building for the new it was looked upon by other congregations with distress and disapproval, and the next thing to giving up their religion itself. This no doubt was only sentiment; but it seems to me if we of this day would cultivate a little more of the true sentiment and love for the pure and beautiful and less of the worldlier sentimental we would live sweeter and more wholesome lives, nearer in a true sense to one another, to nature and to nature’s God.16

Bitch, please, this is Atlanta.

St. Luke’s Cathedral.

Was yesterday finished and will be opened to-day to the public, and is one of the handsomest churches in the city.

It is located on the corner of Houston and Pryor street, facing Peachtree. The plans were drawn by Messrs. Humphreys and Norman [sic], architects. Under their personal supervision it has been built and they have reason to feel proud of it. The contractors, Messrs. Oliver and Carey, and their foreman, Mr. Edward Edge, deserve much credit for the construction. It is of the old English architecture and is much admired. The interior finish in ceiling is Georgia pine left in its natural color, all other woodwork walnut, except the pews which are ash ends and poplar seats and backs, all upright walls are plastered and will be frescoed by Messrs. Sheriden & Bro.

The chancel furniture is being made the Gate City Planing company and will be finished within two weeks and will consist of the bishop’s chair with canopy, altar table with eight foot arch, credance table, two priest’s chairs, two priest’s stalls and kneeling desks, pulpit, two lectern, all walnut except the credence tables, which is made of Virginia pine from the old Blankford church, near Petersburg, Virginia, built in colonial days over one hundred fifty years ago.

The chancel will be enclosed with a brass rail now being made in New York.

The church will be lighted with gas, having one large 20 light chandelier and 12 two light brackets. The organ will be a very fine one and built by Messrs. Pilcher & Co., of Louisville, Ky. Negotiations are now progressing for its constrnction [sic]. The font will be of Tennessee marble and be located at the intersection of the aisles in the body of the church.

A cathedral is the principal church in a diocese and is where the bishop presides and has a seat is the center of his authority.

Atlanta is the residence of the bishop of Georgia and St. Luke’s has been built for the bishop as the cathedral

Space forbids a more detailed description of the new church. The following sessions will be held therein commencing this morning at seven o’clock and continue during Lent:

The Rev. Mr. Beckwith will preach to-day at 11 o’clock, and the Rev. Mr. Williams this evening at 7:30 o’clock.17

References

- Illustration credit: Lyon, Elizabeth A. Atlanta Architecture: The Victorian Heritage, 1837-1918. The Atlanta Historical Society (1976), p. 43. ↩︎

- “St. Luke’s Church Now For Sale By Owner”. The Atlanta Journal, July 29, 1906, p. 12. ↩︎

- “Auction Sale of Central Property.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 6, 1882, p. 3. ↩︎

- “A Verdict Against a Church.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 22, 1882, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Real Estate and Industrial Notes.” The Atlanta Constitution, July 28, 1882, p. 7. ↩︎

- “The Corner-Stone”. The Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 1882, p. 6. ↩︎

- “St. Luke Episcopal Church To Build At Once”. The Atlanta Journal, March 9, 1906, p. 7. ↩︎

- Atlanta, Georgia, 1886 / published by the Sanborn Map and Publishing Co Limited ↩︎

- “The Building Outlook.” The Atlanta Constitution, February 1, 1883, p. 7. ↩︎

- “St. Luke Episcopal Church To Build At Once”. The Atlanta Journal, March 9, 1906, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Big Apartment House On St. Luke’s Site”. The Atlanta Journal, August 1, 1906, p. 15. ↩︎

- “Plans Of New St. Luke Church Completed By Architect Marye”. The Atlanta Constitution, January 12, 1906, p. 3. ↩︎

- “St. Luke Episcopal Church To Build At Once”. The Atlanta Journal, March 9, 1906, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Tearing Down Old Landmark”. The Atlanta Constitution, October 12, 1906, p. 11. ↩︎

- Insurance maps, Atlanta, Georgia, 1911 / published by the Sanborn Map Company ↩︎

- M.S. “The Passing of Old St. Luke’”. The Atlanta Journal, November 11, 1906, p. 6S. ↩︎

- “St. Luke’s Cathedral”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 11, 1883, p. 9. ↩︎

-

“Atlanta Women Win Success in Business” (1913)

Henrietta C. Dozier. W.A. Turner Residence (1913). Newnan, Georgia. The Background

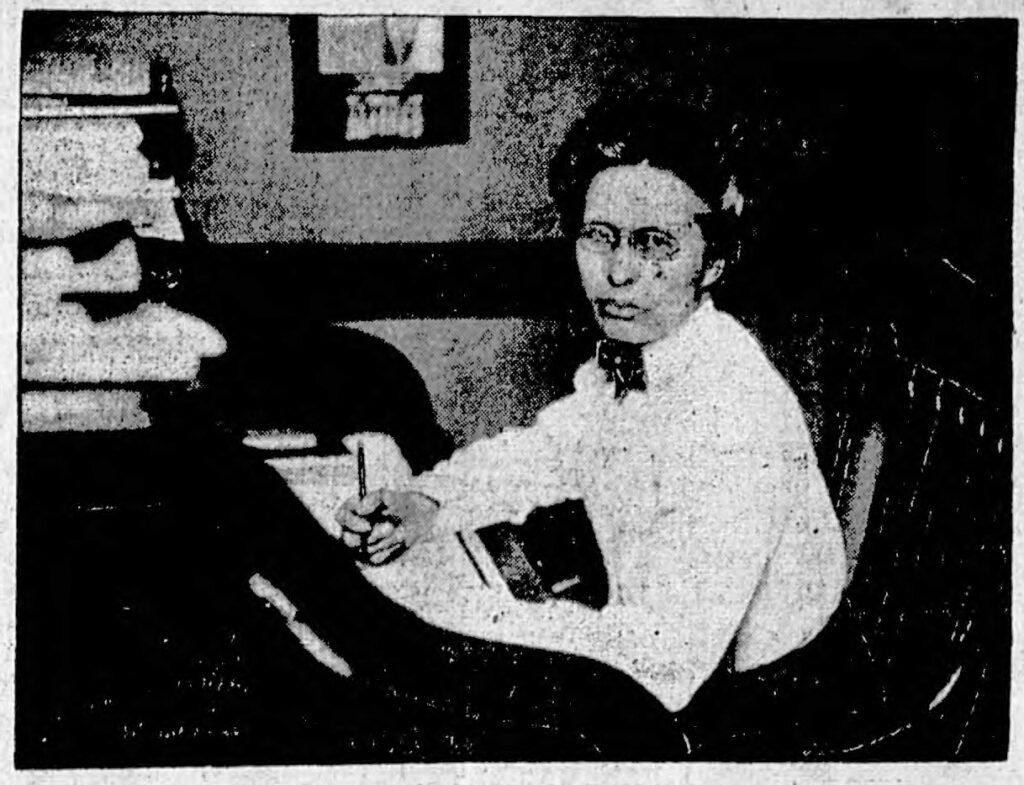

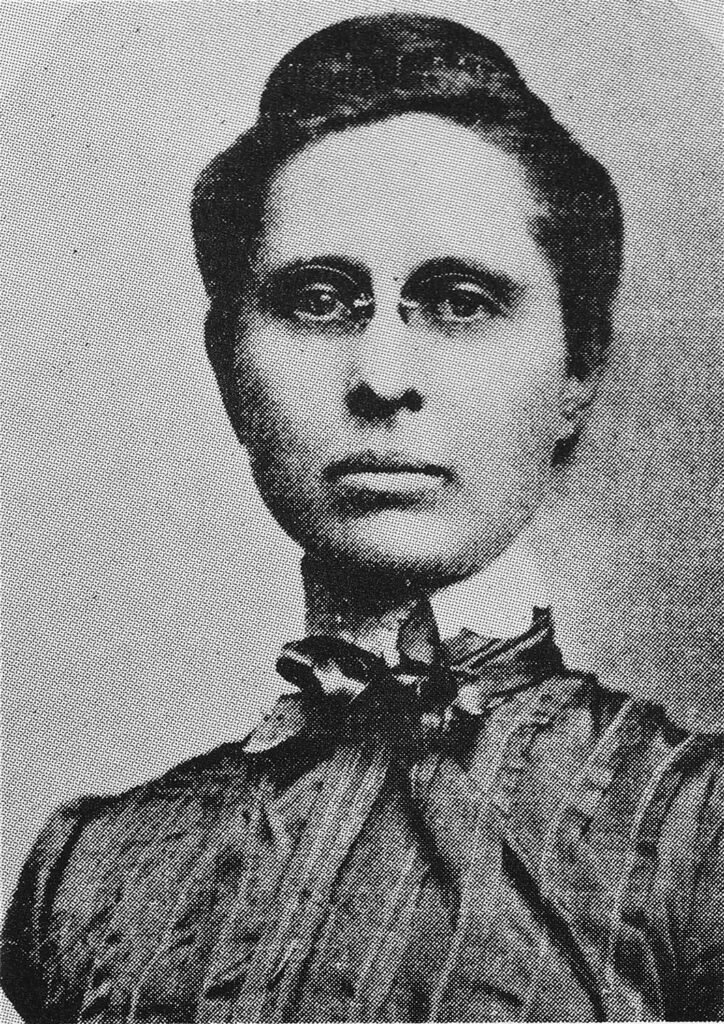

The following excerpt is from an article published in The Atlanta Journal in 1913, featuring an interview with Henrietta C. Dozier (1872-1947), the first female architect in Atlanta and the Southeastern United States.

What a difference 12 years makes. Compared to the first profile of Dozier in 1901, this article about Atlanta businesswomen is downright respectful — the male reporter even puts “weaker” in quotations when mentioning the ‘”weaker” sex.’ Progress!

Women’s suffrage was still 7 years away, but as the article notes, Atlanta women were increasingly making inroads into male-dominated professions, including photography, real estate, medicine, dentistry, and, of course, architecture.

“… it is only a question of time when there will be no typically masculine projects,” the writer opines.

As always, Dozier was characteristically forthright about the difficulties of her profession (“It is a hard life…”) and didn’t hesitate to recognize her role as a pioneer for other women — “It was left for me to open a pathway where other women shall reap success.”

This article is one of just a few that list some of Dozier’s notable projects during her time in Atlanta, making it a particularly valuable research source.

Article Excerpt:

“The old bubble that the north is a better field of business for a woman than the south has been decidedly polted.”

So speaks the woman architect of Atlanta. Another one backs her up, a woman photographer joins her voice in the assertion, a female real estate agent drives it into one ear and tries to sell you a lot through the other, a half a dozen doctors and dentists of the “weaker” sex agree with them.

They do not have to put it into words. It can be seen with half an eye. It is visible in the crowded ante-rooms of the women doctors, in the beautiful pictures in the photographer’s windows, in the scores of blue prints overflowing the architect’s table.

When a woman succeeds in a woman’s work it is not surprising. When a man succeeds in a woman’s work the world is not astonished. But the woman winning success in a business which is properly a man’s, is another matter.

It will not be long, however, before it will be impossible for women to gain distinction in a masculine project, for it is only a question of time when there will be no typically masculine projects. The women are making them their own.

SOUTHERN BUSINESS WOMEN.

In the north and east, even in the west, women have been breaking into business for the last quarter of a century. In the south, in Atlanta, a real business woman is still enough of a rarity to win the public gaze and incidentally the public patronage.

Business women who have tried their hand in Atlanta have tried their hand in the north as well, will tell you that there is no place like the south. Their slogan is an adaptation of Horace Greely‘s “Young girls, come south”.

There is Miss Henrietta Dozier, the woman architect who has had all the business she could handle for the last eleven years. She has had offices in the Peters building for eleven years, she has been in the south but eleven years, she has been successful eleven years.

Not that Miss Dozier is advising any girl to go to work.

“It is a hard life,” she says, “and if I had a daughter, I wouldn’t want her to do architectural or any other kind of work.”

Atlanta should feel proud of Miss Dozier. She is a graduate of the Girls’ High school and has made her name one of the foremost in American architectural circles.

Dozier graduated from Boston Tech, a full-fledged architect. She had accomplished the dream of her girlhood, fulfilled the ambition which was born in her when she used to build houses of A B C blocks and which clung to her all through her High school days.

First, she tried architecture in Boston, and the result is the very reason she likes Atlanta better. South she came, was in Jacksonville for eighteen months, and then reached Atlanta, where she was in the office of Walter T. Downing for another eighteen months.

PIONEER FOR WOMEN.

Eleven years ago she went into business for herself. At the time there was not another woman practicing architecture south of Mason and Dixon’s line. Miss Dozier was the pioneer who blazed the way.

“It was left for me to open a pathway where other women shall reap success,” said Miss Dozier.

Her own success has been far-reaching. Among the best work she has done is on the Nelson Hall school for girls, soon to be erected on Peachtree road; a shooting box for Mrs. Ernest Lorillard in Buford, S.C.; the Southern Ruralist building in Atlanta, an office building at Buchanan [sic], W. Va.; churches in Jacksonville, Fitzgerald, Gainesville, Barnesville; and numerous residences, among them Mr. Blackmar‘s in Columbus, Ga., Bishop Nelson‘s and Arnold Broyles‘ in Atlanta, Dr. W.A. Turner‘s in Newnan.1

References

- Greene, Ward S. “Atlanta Women Win Success In Business”. The Atlanta Journal, June 15, 1913, Women’s Section, p. 3. ↩︎

-

“The Woman Invasion?” (1910)

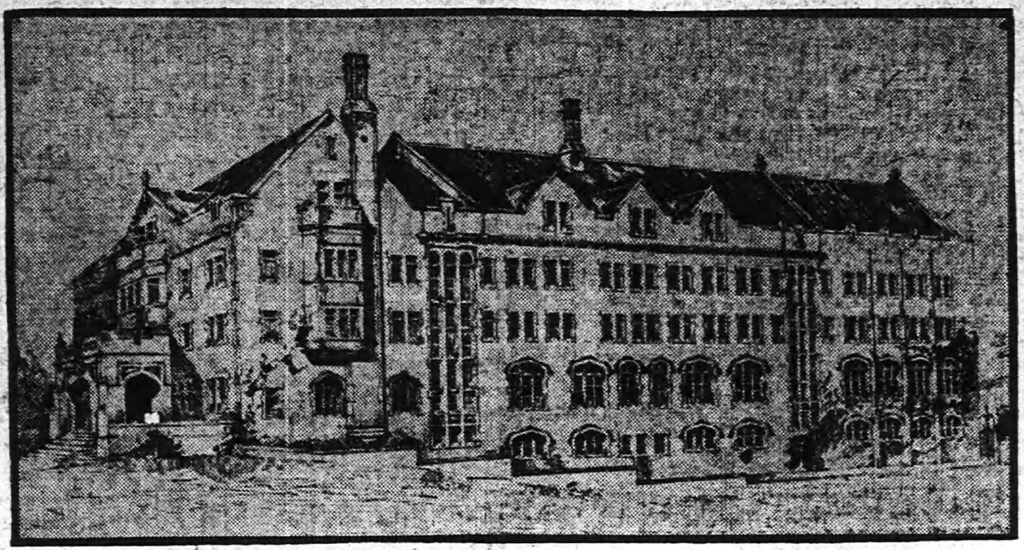

Henrietta C. Dozier. Nelson Hall (1910, unbuilt). Atlanta. Photograph by Abananza Studio of Atlanta.1 The Background

The following article appeared in The Atlanta Georgian and News in 1910, and includes a profile of Henrietta C. Dozier, the first female architect in Atlanta and the Southeastern United States.

While Dozier is the primary subject of the article, another “woman architect” of Atlanta is mentioned, Leila Ross Wilburn, as well as a feisty, anonymous attorney who apparently designed homes as a hobby.

Wilburn was a self-taught designer and unlicensed architect who started her own practice 8 years after Dozier, although she is sometimes erroneously credited as the South’s first female architect.

Her designs were unremarkable, but Wilburn found success by following the lead of architects like George F. Barber, publishing a series of pattern books for those looking to build their own homes inexpensively.

While Dozier is largely forgotten in Atlanta, Wilburn’s work is still widely touted by locals, particularly in nearby Decatur, Georgia, where many homes by her design remain. You will find no such celebration of Wilburn here.

As Dozier notes in this article, the Diocese of Georgia, headed by Bishop C.K. Nelson, commissioned her to design a project called Nelson Hall (pictured above), a 3-story school for girls on Peachtree Street in Atlanta.2 3 4 5 6

Dozier was a devout Episcopalian, and the diocese was her most faithful client in Atlanta:7 among other projects for the organization, she designed the first chapel for Atlanta’s All Saints Episcopal Church,8 9 a 2-story building known as the Southern Ruralist building (1912, demolished),10 11 12 13 14 and St. Michael’s Episcopal Church in Fitzgerald, Georgia, which still survives.

Had Nelson Hall been completed, it would have been one of the major works of Dozier’s career, but the project failed to materialize.

Henrietta C. Dozier, 1910. Photograph by Abananza Studio of Atlanta.15 The Woman Invasion? Here Are Two Women Architects in Atlanta, and They Plan Sure-Enough Houses, Too

Miss Henrietta C. Dozier Talks of Her Work–She Designs Factories and Churches and Any Sort of Building.

By Dudley Glass.

“Why, anything from a chicken coop to a church. But my favorite line? The big things with lots of money in them, of course.”

Miss Henrietta C. Dozier leaned back in her office chair and smiled in a friendly way. She seemed to think it odd that any one should be surprised at a woman’s success in architecture. But, then, women are giving their brothers a race in every line nowadays, except steeple climbing, and it wouldn’t surprise me to see one start that. Why, there’s even a woman—but that’s good enough for a story of its own, so I’ll save it.

“Why not?” asks Miss Dozier. “There’s very little difference between men and women. There’s a lot more difference between individuals. I studied architecture in college, served a long apprenticeship for practical experience and had my ups and downs in the school of practical work. Why shouldn’t I be a good architect? I don’t ask any favors because I am a woman. Can I give satisfaction? That’s the main point.“

No Fashion Plates There.

Certainly she seemed to have sunk the woman in the architect during business hours at least. Her desk, a big roll-top with a hundred pigeon-holes, was well covered with papers and plans. I took a peep at a stack of magazines on the corner and instead of fashion plates and The Ladies’ Home Journal, I found only The Architectural Record and The Engineering Review. There were no Christy sketches on the wall of her office in the Peters building, but a dozen front elevations of handsome buildings, a glimpse or two of the Parthenon and the Coliseum and, in the place of honor over the desk, a big plate of the Boston Atheneum.

No, she isn’t an imported product. Boston furnished some of the science, but Miss Dozier is of the South Southern. You couldn’t chat with her for five minutes without learning that. But she would rather talk of her work than her personality, anyway.

She’s Building Nelson Hall.

“The biggest thing I ever tackled?” repeated the woman architect after a question. “Why, that, I suppose,” pointing at a drawing on the wall. “That” was an elevation of Nelson Hall, the splendid Episcopal school for girls which is soon to be erected on Peachtree-st. by Bishop C.K. Nelson and his diocesan workers.

“That’s been keeping me pretty busy lately,” she continued. “Nice of them to give me such a fine piece of work, isn’t it. Yes, it’s Tudor architecture. It’s going to be very handsome.”

“But I’ve built all sorts of things. There were some little houses at first—you know a beginner takes what she can get—but that was a long time ago. I’ll take a contract for any character of structure, factory, church—I’ve built several churches—homes, but I like the big things best, of course.”

“Do you really get out in the weather and climb over the half-finished buildings and boss contractors and all that sort of thing?” I was wondering if this neatly groomed woman had her troubles with workmen like ordinary folk or if she did all her directing from a steam-heated office.

A Woman as a “Boss”.

“Of course,” she replied. “No, I don’t ‘boss’ anybody much. That isn’t necessary. Every contractor I have known–with one exception–has been nice to me. All I need do is show them what I want.”

Miss Dozier smiled as she recalled the exception. A contractor had used some inferior laths against her express direction. There had been a letter or two, a telephone message, an ultimatum from the architect—and those laths came off again and new ones went in their place. The recollection seemed to amuse her.

“Sometimes they think a woman doesn’t know,” resumed the architect. “I drew plans for a big factory not long ago and had the weights all supported by—” (here she gave a brief but graphic description of her plans.) “The owners insisted that the idea wouldn’t do. No mill had ever been built that way, therefore it wasn’t the right way. And now, right in that late magazine, I find a big factory of the same kind using exactly the same idea I proposed. I’m glad to be vindicated—tho I knew I was right all the time.

“Women clients? No, they are no more trouble than the men. No, I can’t say that women are any more disposed to give another woman work than are the men. You remember I told you men and women were mightily alike. I’ve done lots of work for both.“

And then Miss Dozier begged me to excuse her a moment while she stopped for an animated discussion with a contractor whom she had summoned by phone. The cataract of technical terms that overflowed from the inner office while they bent over plans and blueprints gave me a feeling that I’d been trying to talk a strange language, and I slipped away.

She’s Not the Only One.

But Miss Dozier isn’t the only woman architect in Atlanta, even tho she is perhaps the best known, a natural consequence of her seven years’ service here and her degree from the American Institute of Architects. Just below her in the same building on the third floor, is the office of Miss Leila Ross Wilburn, a young woman who was too busy with pencil and compass when I entered to give much more than a pleasant smile and a promise of a talk some other time. Miss Wilburn, who lives in Decatur, has graduated from drafting for other architects into a nice business of her own, and has pluck and energy enough to accomplish wonders. She did the Goldsmith apartments on Peachtree and Eleventh-sts., the fine gymnasium at the Georgia Military academy and the academy’s Y.M.C.A. chapel and recreation halls, and has successfully completed a number of Atlanta buildings.

And there’s still another–a woman who draws plans and builds houses for herself. I met her in Inman Park, where she was making a hard-headed carpenter hang a door according to her ideas instead of his own.

“Are you an architect?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “I’m a lawyer, and if you write me up in the paper I’ll sue you.”

She wasn’t deceiving me. She really is a full-fledged lawyer, and builds houses merely because she likes the work and the results. But remembering her threat, I’m not going to write her up, not even give you her name.16

References

- “Nelson Hall, The New Episcopal School”. The Atlanta Constitution, March 19, 1910, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Bishop Nelson Will Head School For Young Women”. The Atlanta Journal, July 13, 1909, p. 3. ↩︎

- ‘”Nelson Hall” Charter Granted By Court’. The Atlanta Constitution, July 14, 1909, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Will Open New College For Girls September, 1910”. The Atlanta Georgian and News, July 14, 1909, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Nelson Hall, The New Episcopal School”. The Atlanta Constitution, March 19, 1910, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Miss Stewart Here To Represent Nelson Hall”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 5, 1911, p. 5. ↩︎

- Spotlight: Henrietta Dozier – Jacksonville History Center ↩︎

- “History of All Saints’ Parish and Church Just Complete”. The Atlanta Constitution, April 8, 1906, p. 2. ↩︎

- “All Saints’ Episcopal Church Will Be Formally Opened This Morning With Beautiful And Impressive Service”. The Atlanta Journal, April 8, 1906, p. S1. ↩︎

- “Church Asks Permit To Erect $23,00 Building.” The Atlanta Georgian, July 3, 1912, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Episcopalians May Erect Big Building”. The Atlanta Journal, July 3, 1912, p. 2. ↩︎

- “The Real Estate Field”. The Atlanta Journal, July 8, 1912, p. 19. ↩︎

- “The Real Estate Field”. The Atlanta Journal, August 1, 1012, p. 19. ↩︎

- “Wanted–Female Help.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 15, 1912, p. 5. ↩︎

- Glass, Dudley. “The Woman Invasion? Here Are Two Women Architects In Atlanta, And They Plan Sure-Enough Houses, Too.” The Atlanta Georgian and News, February 19, 1910, p. 1. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

-

“Miss Henrietta C. Dozier, Architect, Talks of Congress in Vienna” (1908)

Henrietta C. Dozier. John Blackmar Residence (circa 1910 renovation and expansion). Columbus, Georgia.1 2 3 The Background

The following article was published in The Atlanta Journal in 1908, featuring an interview with Henrietta C. Dozier (1872-1947), the first female architect in Atlanta and the Southeastern United States.

In 1908, Dozier was chosen by the Atlanta chapter of the American Institute of Architects as its delegate to the International Congress of Architects in Vienna, prompting her to spend 4 weeks in Paris before attending the conference, followed by visits to Venice, Florence, Rome, Naples,4 5 6 and other destinations.

A European excursion was an obligatory rite of passage for any American architect of the era — at least, those who were serious about the profession. The United States was then in the throes of the Beaux-Arts movement, and architects were expected to examine the works of their European forebears for inspiration.

“Strange to say, the architecture of Europe did not particularly interest me,” Dozier later recalled in a 1939 interview, which mirrored her remarks here.

The writer of this article (also a woman) wanted an architect’s impressions of Europe, and she got them — Dozier found Vienna “disappointing” and Brussels “not very interesting”. On the flip side, she thought Antwerp was “perfectly fascinating” and enjoyed the fashions of the “chic Parisiennes”, although she barely mentioned Paris’ architecture. Priorities.

Dozier inserted some interesting observations about American indifference toward architecture, and she pointedly criticized the preferential treatment given to her male colleagues at the conference: “I don’t mind adding that the men had altogether the best of it when it came to getting particular good from the congress, as on especial meetings the women were packed off on some excursion…”

Given her unorthodox character, it seems entirely fitting that Dozier broke away from those excursions (“I did my own sight-seeing in my own way…”), and that she got “forbidden snapshots” with her Kodak camera “in spite of the signs and guards”. My kind of woman.

Miss Henrietta C. Dozier, Architect, Talks of Congress in Vienna

“I have been interviewed several times and I don’t think the interviewer ever got what he wanted from me.”

This from Henrietta Dozier, architect, in answer to a question regarding her recent trip abroad.

[Reporter:] “Perhaps I am not as hard to please as those others; I only want to know something about the purpose of your journey.”

[Dozier:] “I was a delegate to the National Congress of Architects which met in Vienna, a congress representing Italy, France, Germany, Russia, England and America. There were about five hundred delegates, several hundred of them women. I don’t mind adding that the men had altogether the best of it when it came to getting particular good from the congress, as on especial meetings the women were packed off on some excursion about the town or its environments. None of that for me, however. I did my own sight-seeing in my own way and got a world of good out of my half loaf of travel. As for the purpose of the congress it is primarily to arouse greater interest on the part of the different governments for a purer architecture to appoint a commission by the government to make laws whereby it will be impossible for an unsightly building to be built by one ranking in the thousands; to have some rules so that in time each country will show not only a few perfect buildings but that there will be a harmony in the whole. It seems a gigantic undertaking but in Europe architects have an important share in the making of the cities and in the brighter and more hopeful interest taken in civic improvement it may not be long before they will come into their own in America.”.

“What do I think of Vienna? I found it disappointing. It is all so new—the best of their buildings are modeled from the classic—there is nothing original in them. The best thing except for St. Stephens‘, are the new parliament buildings, but they are distinctly similar to the new university at Athens, and Greece has accomplished nothing better than the ancients and know enough to cling to their ideals. St. Stephens’ is delightful and quite, to my mind, the best thing in Vienna. The rest of the city I found German,” (which, parenthetically, would arouse the ire of both Austrians and Germans could they hear it.)

Dormer and cornice on John Blackmar Residence Miss Dozier, builder though she is, in brick and stone, is not above a weakness for the creations in less lasting fabrics, and confesses to a keen admiration for the chic Parisiennes and fashions of the Rue de la Paix, Paris.

But in Paris she found the best in architecture.

“They are clever, those Frenchmen, nobody is their equal in planning and proportion. One of the finest things I have ever seen in my life is Napoleon’s tomb, and it took a Frenchman to do it—that marvelous management of lighting, the effect of moonlight gained by the use of pale yellow and blue glass there is nothing like it in the world. It is only in their detail that they overdo. I don’t understand why they do it. Planned and proportioned perfectly they will stick a lot of silly detail on that will come near to ruining their entire piece of work.”

“Perhaps that is as characteristic as the stolidness you find in German architecture.”

“Perhaps it is the super adornment, the ornateness, the extra trimming both in manner and building, but oh, they are so clever.

“I saw an architectural exhibit in the Salon and there was nothing like it for beauty of outline or plan.”

“No the Salon was not particularly interesting. Of course there were some good things, but I was surprised at the acceptance of some of the pictures; they were far below the usual standard.”

[Reporter:] “That wouldn’t be if all artists had the ideals of Monet.”

“No, indeed, it must have taken nerve to destroy £20,000 worth of pictures without taking into consideration the time and effort he must have put into them. Coming back to architecture, it hurts so to see the prevailing indifference of America to what architecture really means, so little realization of what a telling criticism a building of stone is on generations of the past. How ignorance endures in stone and how, when well done, what a monument to knowledge and culture.

Corinithian capital on John Blackmar Residence [Reporter:] “Don’t you think, architecturally speaking, that the south has deteriorated since the [Civil] war instead of growing?”

“Oh, no; not at all, the people as a whole, are building better and more harmonious homes than ever before.

“Of course in the ante-bellum south the homes were modeled, many of them, from places already old when America was young. Built by men who wanted to bring with them the atmosphere of England to the new world—cultured students—men who knew the difference between cornices and capitals and who knew better than to confuse Gothic with Doric. A great deal of trouble comes from magazines. Not that I wish to underrate the undeniable good that magazines do, for they do a great deal in bringing to the people a broader, better view on homes and home surroundings. If the readers were only educated enough to differentiate between the bad and the good. But a little knowledge is as dangerous in architecture as it is in most things and people who have not made it a study and who wish to build would do well to leave it some one who has made it a specialty. Atlanta has made a great stride forward in the appointment of a civic improvement commission and we can hope for a more beautiful, a more harmonious Atlanta.

“And it is along these lines that the commission of the International Congress is working.

Enclosed porch on John Blackmar Residence “The meeting in Vienna was the eighth which has been held and there were delightful social features in connection with the more interesting business ones. A reception at which Frances Joseph [sic] entertained the delegates, another charming one at Sehonbrun [sic], the summer palace, carriage drives on the Ringstrasse [sic] and out into the Danube valley and a number of formal affairs at private homes.

“About the rest of my trip? There was the landing and a stay of several days at Antwerp that I found perfectly fascinating. Antwerp is a place you could stay and long time in and not get tired of it. Then from there to Brussels which is not very interesting to me, and I only stayed for a short time on the way to Paris, where I spent three weeks, and to where I am going back at my first opportunity. Basle was attractive and I had a delightful stay in Salzburg and Munich, then Linz, where I took the boat for Vienna on the Danube. From Vienna I went to Venice, Rome and Naples from which point I sailed. It was a nice half-loaf, but it made me hungry for the other half, and the next time I go I hope to stay longer and see more.”

Miss Dozier took a number of interesting kodak pictures and in spite of the signs and guards, got views of San Angelo, interior details of St. Peter’s and a series of forbidden snapshots in the French capital.

MABEL DRAKE.7

References

- “Personal and Incidental.” The Columbus Enquirer-Sun (Columbus, Georgia), October 17, 1909, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Wanted–Driver and Butler.” (classified advertisement) The Columbus Ledger (Columbus, Georgia), September 25, 1910, p. 2. ↩︎

- “Mrs. Blackmon’s Bridge Party”. The Columbus Enquirer-Sun (Columbus, Georgia), March 5, 1911, p. 2. ↩︎

- “Miss Dozier Goes Abroad.” The Atlanta Constitution, April 5, 1908, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Miss Dozier Sails On European Trip”. The Atlanta Journal, April 5, 1908, p. 24. ↩︎

- “Some Personal Mention”. The Atlanta Journal, April 5, 1908, p. 39. ↩︎

- Drake, Mabel. “Miss Henrietta C. Dozier, Architect, Talks of Congress in Vienna” The Atlanta Journal, June 19, 1908, p. 13. ↩︎

-

“This Georgia Woman Stands High In Her Profession” (1902)

Henrietta C. Dozier (attributed). G.W. Gignilliat Residence. Seneca, South Carolina.1 The Background

Henrietta Cuttino Dozier (1872-1947), professionally known as Henrietta C. Dozier, was the first female architect in the Southeastern United States, practicing in Atlanta from 1901 to 1914, and then in Jacksonville, Florida, for the remainder of her life and career.

The United States had 22 female architects by 1895,2 which increased to over 200 by 1920.3 Beginning in the 1890s, the slow but steady rise of women in male-dominated professions, including architecture, spurred a flurry of press articles, with claims of a “woman invasion” stoking fierce public reaction — keep in mind, women weren’t even allowed to vote until 1920.

Atlantans’ first exposure to a “lady architect” came during the development of the Cotton States and International Exposition in 1894, when plans for the Women’s Building were solicited exclusively from female designers — a radical proposal at the time.

Upon seeing the submitted plans, T. H. Morgan of Bruce & Morgan reportedly remarked: “Why, these buildings are bold enough to have been drawn by men.”4

Elise Mercur of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, secured the commission for the women’s building, winning over 12 other submissions, including one by Dozier, who was then studying at the Pratt Institute in New York.5 6 Dozier entered Pratt as its only female student, ranking second in her class.7

Dozier (pictured here8) was born in Fernandina Beach, Florida, but raised in Atlanta by her single mother — her father died 4 months before she was born.9 She attended the Atlanta public schools before heading north, where she studied at Pratt and later the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), graduating in 1899 with a B.S. in Architecture10 — one of just three women in a class of 176 students.11

An unconventional woman for her era, Dozier never married, reportedly dressed in men’s clothing, and was known to her friends and family as “Harry” and “Uncle Harry”12 13 14 — draw your own conclusions.

In 1893, The Atlanta Journal described “Harry Dozier” as “a young girl of unusual force and mental determination. She is quite young, and quite handsome…”15

Dozier learned to fly airplanes in her 60s,16 and following her death, her relatives were surprised to discover a manuscript she had written for an unpublished romance novella. Sample text:

“Men do not get what they deserve in life, they get what they go after,” said Elizabeth. “So? My dear, I think women do a lot of going after what they want also … At least, you know how to get what you want.”17

Only one of Dozier’s known works survives in Atlanta: a residence she designed for Mrs. O.K. Slifer on 10th Avenue overlooking Piedmont Park. The structure now serves as a school building and has been altered.

Henrietta C. Dozier. O.K. Slifer Residence (1912, altered). Atlanta.18 19 Although Dozier often downplayed her professional difficulties in interviews, there is ample evidence that she faced severe discrimination in a field that largely remains an old boys’ club. As one article noted in 1903: “It is only recently that the men in the profession began to regard women architects as other than a huge joke.”20

Dozier wasn’t a spectacular designer by any means, but she also wasn’t given nearly as many opportunities to refine her skills as her male counterparts, securing few large-scale commissions throughout her career. In a 1939 interview, she noted: “…in the last few years, I have done nothing but small residential homes.”

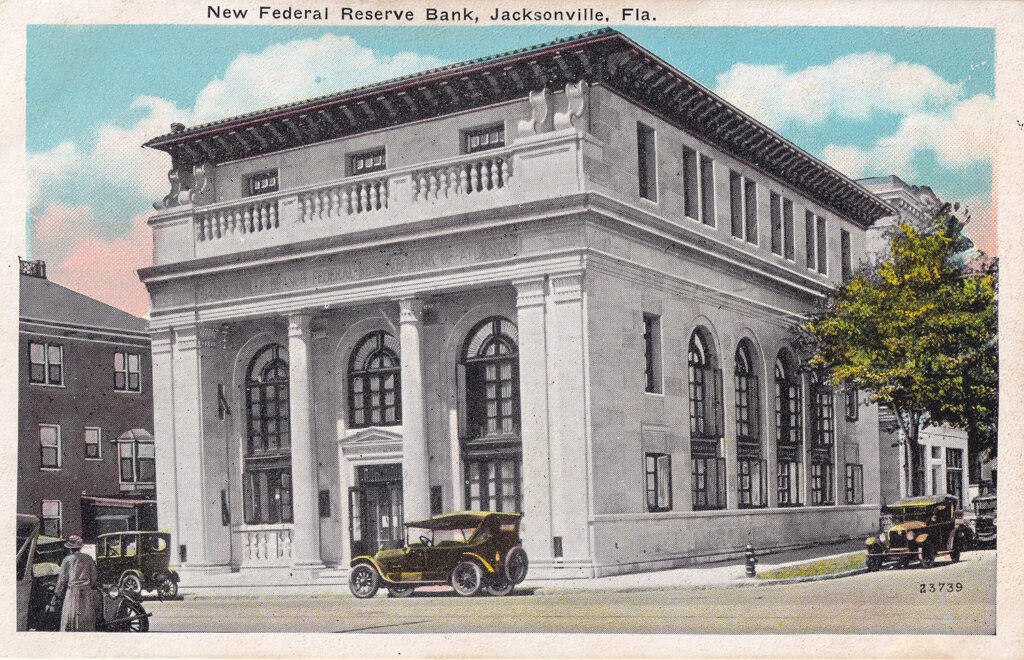

Dozier said she was “always very proud” of her work on the Jacksonville branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta,21 which can easily be considered her finest effort. She was officially credited as supervising architect for the project, working under A. Ten Eyck Brown of Atlanta. However, Brown often claimed credit for projects he had little to no hand in designing, and it appears Dozier did most of the work.

A. Ten Eyck Brown with Henrietta C. Dozier. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Jacksonville Branch (1924), Jacksonville, Florida.22 Photograph from an undated postcard. In 1905, Dozier was elected an Associate of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), only the third woman to be accepted into the organization.23 Dozier’s election directly led to the establishment of the Atlanta chapter of the AIA,24 which later became AIA Georgia.

As T.H. Morgan recounted, a minimum of five AIA associates were required to form an AIA chapter, and Dozier, along with Harry Leslie Walker, became the fifth and sixth architects in the city elected as associates, prompting the chapter’s organization.25

During her life, Dozier’s work was barely acknowledged by the press — in either Atlanta or Jacksonville. The handful of news stories written about her often conveyed a tone of curious skepticism, if not outright ridicule.

The following article, published in The Atlanta Constitution in 1902, is the first of just a few that were written about Dozier during her time in Atlanta, and it’s as sexist and condescending as it gets.

Dozier had been in practice less than 2 years, and the reporter (obviously male) depicted her interest in architecture as some girlish lark before settling into marriage, claiming that she “makes plans for a future fair with promise, where she may realize a woman’s dreams of ease and mental and domestic pleasure, surrounded by the friends she loves—nature and children and dumb things.”

Maybe that’s what Dozier told the reporter to keep him happy, but she clearly had other ideas for herself.

This Georgia Woman Stands High in Profession of Architecture

“Of all the branches of work into which women are entering there is none which shows so small a percentage of the really successful as that of architecture, and this is particularly true in the south. Two reasons deter the young woman casting about for something upon which to settle. In the first place, it is hard work; in the second, there is the probability of marriage—the state few on the sunny side of twenty-five or thirty could be brought to regard as anything but the ultima thule to which woman existence tends. And when one there is who from choice enters seriously upon a real profession the world might as well see at once, what sooner or later it will have to see, that she will succeed.

When Miss Henrietta C. Dozier entered as apprentice in an architect’s office she set herself to work as a man does—not simply to bridge over a year or two until the time when she would marry—she began at the beginning and held on to the finish. A year of apprenticeship was followed by two at Pratt Institute; then after some months in New York she went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, remaining four years. Coming south, she opened an office in Jacksonville, Fla., where she was in business six months, but in compliance with solicitations from friends in Atlanta decided to remove to this place, where she is permanently located and established, doing business with a man’s understanding and knowledge and a woman’s thoroughness and regard for detail.

Architecture is peculiarly suited to woman from the fact that her ideas on the requirements of a house are more practical than those of a man. Too, if she has first an all-round knowledge of mechanics her artistic instinct will serve her well. Miss Dozier, realizing what a woman wants and knowing how to go about having it, has built her own house—a unique and picturesque cottage, modern and complete, and meeting her needs as nobody else could have planned for her.

Here, in her hours of recreation, she enjoys with her mother and sister the sweetness of home, and makes plans for a future fair with promise, where she may realize a woman’s dreams of ease and mental and domestic pleasure, surrounded by the friends she loves—nature and children and dumb things.

Miss Dozier, like Dorothy Manners, has “the generations” back of her. Her forbear, Thomas Smith, of South Carolina, was landgrave in 1663, or there abouts, and a long line of ancestors have bequeathed to this young woman the intrepid spirit which no mere circumstance can daunt, and placed in her slender hand the key which unlocks every door—a will that brooks no thwarting.

As an architect she is a success; she has mastered her profession and she makes it pay.26

References

- Wells, John E. and Dalton, Robert E. The South Carolina Architects, 1885-1935: A Biographical Dictionary. Richmond, Virginia: New South Architectural Press (1992), p. 42. ↩︎

- “Uncle Sam And The New Woman.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 30, 1895, p. 32. ↩︎

- Allaback, Sarah. The First Women Architects. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press (2008), p. 2. ↩︎

- “Current Events From A Woman’s Point Of View.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 2, 1894, p. 6. ↩︎

- “Plans By Fair Hands”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 28, 1894, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Tiffany Will Be Here.” The Atlanta Journal, November 28, 1894, p. 6. ↩︎

- “Society”. The Atlanta Journal, March 18, 1893, p. 2. ↩︎

- Photo credit: Wood, Wayne W. Jacksonville’s Architectural Heritage: Landmarks for the Future. Jacksonville, Florida: University of North Florida Press (1989), p. 9. ↩︎

- Spotlight: Henrietta Dozier – Jacksonville History Center ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Atlanta Girl Is Lionized.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 8, 1899, p. ↩︎

- “Society”. The Atlanta Journal, March 18, 1893, p. 2. ↩︎

- Parks, Cynthia. “‘Cousin Harry’ Practiced What She Built”. The Florida Times-Union (Jacksonville, Florida), July 18, 1976, p. G-2. ↩︎

- Weightman, Sharon. “They called her Harry”. The Florida Times-Union (Jacksonville, Florida), July 10, 1994. p. D-4. ↩︎

- “Society”. The Atlanta Journal, March 18, 1893, p. 2. ↩︎

- ↩︎

- Weightman, Sharon. “They called her Harry”. The Florida Times-Union (Jacksonville, Florida), July 10, 1994. p. D-4. ↩︎

- “The Real Estate Field”. The Atlanta Journal, October 31, 1911, p. 19. ↩︎

- “Some Personal Mention”. The Atlanta Journal, January 28, 1912, p. L5. ↩︎

- Chapman, Josephine Wright. “Do Women Architects Underchage?” The Atlanta Journal, November 14, 1903, p. 15. ↩︎

- Spotlight: Henrietta Dozier – Jacksonville History Center ↩︎

- “New Federal Reserve Bank Home”. The Sunday Times-Union (Jacksonville, Florida), June 1, 1924, p. 19. ↩︎

- Weightman, Sharon. “They called her Harry”. The Florida Times-Union (Jacksonville, Florida), July 10, 1994. p. D-4. ↩︎

- Morgan, Thomas H. “The Georgia Chapter of The American Institute of Architects”. The Atlanta Historical Bulletin, Volume 7, No. 28 (September 1943): pp. 89-90. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “This Georgia Woman Stands High In Profession of Architecture”. The Atlanta Constitution, October 12, 1902, p. 6. ↩︎

-

Greenville County Courthouse (1918) – Greenville, South Carolina

P. Thornton Marye. Greenville County Courthouse (1918). Greenville, South Carolina.1 2 3 References

- “Atlanta Architect Honored.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 13, 1915, p. 12 B. ↩︎

- “Invitation For Proposals.” The Greenville Daily News (Greenville, South Carolina), November 21, 1915, p. 6. ↩︎

- “First Court In New Court House”. The Greenville Daily News (Greenville, South Carolina), March 26, 1918, p. 5. ↩︎

-

The Priest’s House (1884) – Atlanta

E.G. Lind. The Priest’s House at Catholic Shrine of the Immaculate Conception (1884). Atlanta.1 2 3 4 5 References

- Belfoure, Charles. Edmund G. Lind: Anglo-American Architect of Baltimore and the South. Baltimore, Maryland: The Baltimore Architectural Foundation (2009). ↩︎

- “Notice to Builders & Contractors”. The Atlanta Constitution, June 25, 1884, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Building Bits.” The Atlanta Constitution, May 30, 1884, p. 7. ↩︎

- “The Priest’s House”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 9, 1884, p. 9. ↩︎

- “A Brilliant Occasion.” The Atlanta Constitution, November 12, 1884, p. 7. ↩︎

-

W.W. Goodrich on Henry W. Grady (1891)

Alexander Doyle. Henry. W. Grady Monument (1891). Atlanta. The Background

Henry W. Grady (1850-1889) was the editor of The Atlanta Constitution in the 1880s, as well as the originator and chief proselytizer of “The New South” mythology that Atlanta still clings to as gospel.

If anyone in post-Civil War America was unaware of Grady’s conception of the New South, he considered it his life’s mission to indoctrinate them, criss-crossing the United States and preaching his message of a resurgent South in a series of public speeches.

Grady’s big idea was to decrease the Southeast’s economic reliance on agriculture and attract industry to the region with cheap labor, envisioning Atlanta as its epicenter.

The city and mythology soon became synonymous, and Atlanta developed a reputation as a progressive, “wide-awake” metropolis in a region that had long been viewed as backward and rural.

The vision of the New South was anything but progressive, however, and Grady was simply regurgitating the stale promises of capitalism with a Southern twang.

He was also an avowed white supremacist who lamented the region’s “Negro problem,” which is to say, that Black people existed at all. Among some of Grady’s choice remarks on the subject is this subtle proclamation:

But the supremacy of the white race of the South must be maintained forever, and the domination of the negro race resisted at all points and at all hazards, because the white race is the superior race.1

In other words, the New South was to be built on the same old bullshit as the Old South.

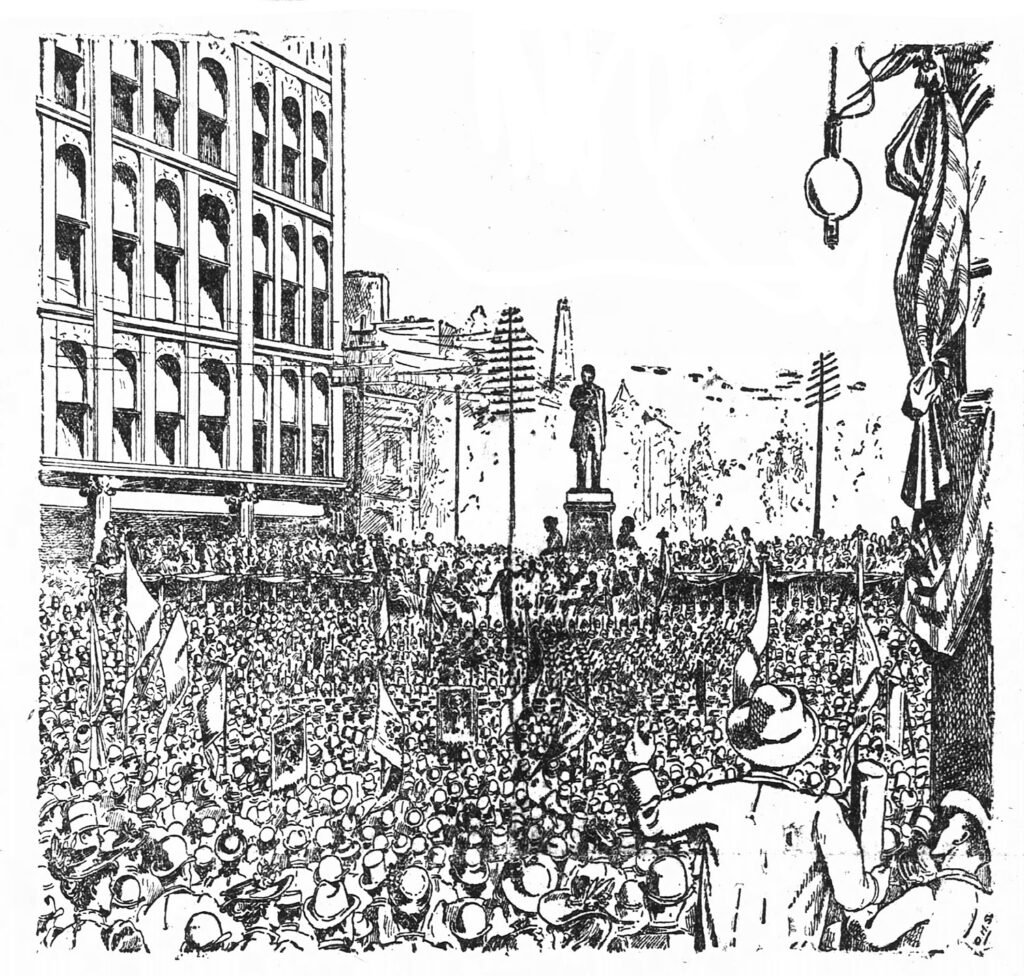

Illustration of the unveiling of the Henry W. Grady Monument, October 21, 18912 Americans love to deify racist orators, and when Grady suddenly died in December 1889, he was immediately beatified by white Atlantans as some patron saint of the city. A movement quickly grew to erect a monument to him, and in March 1890, a local committee accepted the design for a bronze statue sculpted by Alexander Doyle.3

The Henry Grady monument was unveiled in a lavish public ceremony on October 21, 1891,4 which the Constitution predictably covered as if it were the event of the century, claiming that crowds in attendance ranged from 25,000 to 50,000 people,5 no doubt greatly exaggerated since the city’s population was less than 70,000 at the time.6

A monument to Grady wasn’t enough, however, and for decades the city slapped his name on various streets and buildings, including Grady Memorial Hospital and Grady High School in Midtown. The high school finally dropped his name in 2021,7 but the hospital remains “Grady”, and it’s hard to imagine a world in which Atlantans would ever call it anything else.

The Grady monument was erected at the intersection of Marietta and Forsyth Streets, and during the 1906 Atlanta race massacre, it served as an altar for the bodies of three Black men murdered by an angry white mob.

As the Constitution told the story:

One of the worst battles of the night was that which took place around the postoffice. Here the mob, yelling for blood, rushed upon a negro barber shop just across from the federal building.

“Get ’em. Get ’em all.” With this for their slogan, the crowd, armed with heavy clubs, canes, revolvers, several rifles, stones and weapons of every description, made a rush upon the negro barber shop. Those in the first line of the crowd made known their coming by throwing bricks and stones that went crashing through the windows and glass doors.

Hard upon these missiles rushed such a sea of angry men and boys as swept everything before them.

The two negro barbers working at their chairs made no effort to meet the mob. One man held up both his hands. A brick caught him in the face, and at the same time shots were fired. Both men fell to the floor. Still unsatisfied, the mob rushed into the barber shop, leaving the place a mass of ruins.

The bodies of both barbers were first kicked and then dragged from the place. Grabbing at their clothing, this was soon torn from them, many of the crowd taking these rags of shirts and clothing home as souvenirs or waving them above their heads to invite to further riot.

When dragged into the street, the faces of both barbers were terribly mutilated, while the floor of the shop was met with puddles of blood. On and on these bodies were dragged across the street to where the new building of the electric and gas company stands. In the alleyway leading by the side of this building the bodies were thrown together and left there.

At about this time another portion of the mob busied itself with one negro caught upon the streets. He was summarily treated. Felled with a single blow, shots were fired at the body until the crowd for its own safety called for a halt on this method, and yelled “Beat ’em up. Beat ’em up. You’ll kill good white men by shooting.”

By way of reply, the mob began beating the body of the negro, which was already far beyond any possibility of struggle or pain. Satisfied that the negro was dead, his body was thrown by the side of the two negro barbers and left there, the pile of three making a ghastly monument to the work of the night, and almost within the shadow of the monument of Henry W. Grady.

So much for the city too busy to hate.

The Grady statue still stands at the intersection of Marietta and Forsyth Streets in Downtown Atlanta, but it’s easy to overlook. In June 1996, it was moved 10 feet from its original spot for greater visibility,8 but it remains surrounded on both sides by a canyon of glass and steel buildings that casts the monument in near-constant shadow — that’s probably for the best.

When the statue was unveiled in 1891, W.W. Goodrich felt the need to offer his thoughts on the subject — because of course he did — with remarks to the Constitution that should be viewed with great skepticism, given his well-noted propensity for lying.

In the following article excerpt, Goodrich claims to have had “several conversations” with Grady — “in his sanctum,” no less –and acts as if the two men were intimate friends.

Let’s do some quick math here: Goodrich came to Atlanta in September 1889,9 and Grady died on December 23, 1889, after a month-long bout of pneumonia, during which time he also took extended trips to New York and Boston.10

Would a no-name newcomer from California have been able to engage in “several conversations” with Grady in under 3 months? I have serious doubts.

Here, Goodrich also compares Grady to Abraham Lincoln, with whom he was apparently quite enamored [see also: “The President and the Bootblack“], sharing an apocryphal tale about Lincoln that he undoubtedly pulled straight from his ass.

And on that note, we won’t be hearing much more of Goodrich’s bullshit for a while. Thank God.

Article Excerpt:

All during the day, and away into every night, there is a group around the Grady statue. Yesterday it was surrounded all day by men, women and children, who were studying the bronze figure. As late as 10 o’clock last night there were at least twenty people in front of the statue, gazing at it.

Mr. W.W. Goodrich, the architect, says:

Looking upon that face in living bronze, studying its points of character, the many thoughts of the several conversations I had with him pass in review before my memory. Shortly after making Atlanta my home, I called upon Mr. Grady in his sanctum. Always courteous, cordial, and painstaking in a marked degree, to make a stranger at home, in his beloved city, was he to every one. He never referred to the past, but that he predicted from out of it would arise in the south, in this favored region, the grandest lives of our future republic. He predicted that the mighty forces of science would hereabout establish those appliances of labor that would elevate the new south above her most rosy anticipations.

“And why not,” said Mr. Grady to me once, “about us all are the minerals, inexhaustible, that are used in manufacturing enterprises. Our fields give us the raw material for our spindles to manipulate, our firesides are aglow with fuel from nearabout, our food products can all be raised here, our climate cannot be excelled, our transportation facilities place us speedily in all the markets of the world. Again, the active hands behind all this are young men who were boys after the surrender. From bank presidents down to humble vocations, our young men are the leading spirits.”

And whilst I listened to the speeches of Mr. Clark Howell and his co-laborers, at the unveiling ceremonies last Wednesday, I could not help but think of Mr. Grady’s remarks: “Our young men are back of it all, and are the active hands in the forwarding of all this remarkable prosperity and progress.”

Atlanta is peculiarly a city of young men. Their influence is felt on every hand, in every vocation, trade or profession. The brainy young men are back of it all, of all this wonderful and real prosperity, of all this great progress, and the future greatness of our city can be ascribed to the young men. And Mr. Grady was a young man. His addresses show the fire of youth with the mannered culture of experience. The young men of the new south are her bone and sinew, the coming giants in the political arena. The star of empire, for solid practical government, that government of the people, for the people, and by the people, that government of genuine Americans for Americans, is here in the south. From my observation, I verily believe there is more Americanism in the south than in all the rest of the country put together; and more love of American institutions for what they have been, for what they are and for what they will be in the future.

Mr. Grady admired the character of Lincoln, and with emotion remarked that the south lost her best friend when Mr. Lincoln died. He stated that Washington and Lincoln were the two greatest men of the world. And Governor Hill, in his remarkable eulogy of Mr. Grady, at the unveiling ceremonies, likened Washington, Lincoln and Grady as the three greatest men of our country.

Having occasion to visit Philadelphia during the early part of the war, Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward were in a car with several distinguished confederate soldiers on parole. These gentlemen were personally known to Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward, and as they chatted together in a most cordial manner, one of the confederate officers said: “Mr. President, what think you of the war?” Grasping the subject instantly, Mr. Lincoln asked:

“General, what do you think of the old flag?” The general’s color instantly turned and he did, not answer. Rising from his seat across the aisle he paced up the car and back to Mr. Lincoln’s seat and finally replied: “Right there was the south’s mistake.” “Yes,” said Mr. Lincoln, “had the south come north with the old flag, there would have been no war.”

I asked Mr. Grady is he had ever heard of the above conversation. He said that he had from one of the generals who was with Mr. Lincoln at that time. He stated the general’s name, and this same general was a very prominent man in the confederacy, and also stated that Mr. Lincoln’s remark about the old flag, was the truth.

Referring to this conversation, at a subsequent interview, Mr. Grady said: “There as one distinct thought that occurs to me, and that is this, Mr. Lincoln was peculiarly a man of the masses, and not of the classes.” Mr. Grady was a man of the masses, and not of the classes, and therein he was like Mr. Lincoln. His strong position with the masses made his paper, The Constitution, to be read by untold thousands all over the country, who saw in the new south that future of prosperity and progress that was typical in Mr. Grady’s greatness of heart, and of which he was the prime mover and its unflinching champion.11

References

- Life and Labors of Henry W. Grady. Atlanta: H.C. Hudgins & Co. (1890), p. 186. ↩︎

- The Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 1891, p. 1. ↩︎

- “The Grady Monument”. The Atlanta Constitution, March 6, 1890, p. 3. ↩︎

- “In Living Bronze.” The Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 1891, pp. 1-2. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Biggest Cities in Georgia – 1890 Census Data ↩︎

- Midtown High School (Atlanta) – Wikipedia ↩︎

- “Grady Moved By Olympics”. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 14, 1996, p. E1. ↩︎

- “Comes Here to Live.” The Atlanta Constitution, September 18, 1889, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Henry Grady Dead!” The Atlanta Constitution, December 23, 1889, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Etched And Sketched.” The Atlanta Constitution, October 26, 1891, p. 4. ↩︎