The Background

Henry W. Grady (1850-1889) was the editor of The Atlanta Constitution in the 1880s, as well as the originator and chief proselytizer of “The New South” mythology that Atlanta still clings to as gospel.

If anyone in post-Civil War America was unaware of Grady’s conception of the New South, he considered it his life’s mission to indoctrinate them, criss-crossing the United States and preaching his message of a resurgent South in a series of public speeches.

Grady’s big idea was to decrease the Southeast’s economic reliance on agriculture and attract industry to the region with cheap labor, envisioning Atlanta as its epicenter.

The city and mythology soon became synonymous, and Atlanta developed a reputation as a progressive, “wide-awake” metropolis in a region that had long been viewed as backward and rural.

The vision of the New South was anything but progressive, however, and Grady was simply regurgitating the stale promises of capitalism with a Southern twang.

He was also an avowed white supremacist who lamented the region’s “Negro problem,” which is to say, that Black people existed at all. Among some of Grady’s choice remarks on the subject is this subtle proclamation:

But the supremacy of the white race of the South must be maintained forever, and the domination of the negro race resisted at all points and at all hazards, because the white race is the superior race.1

In other words, the New South was to be built on the same old bullshit as the Old South.

Americans love to deify racist orators, and when Grady suddenly died in December 1889, he was immediately beatified by white Atlantans as some patron saint of the city. A movement quickly grew to erect a monument to him, and in March 1890, a local committee accepted the design for a bronze statue sculpted by Alexander Doyle.3

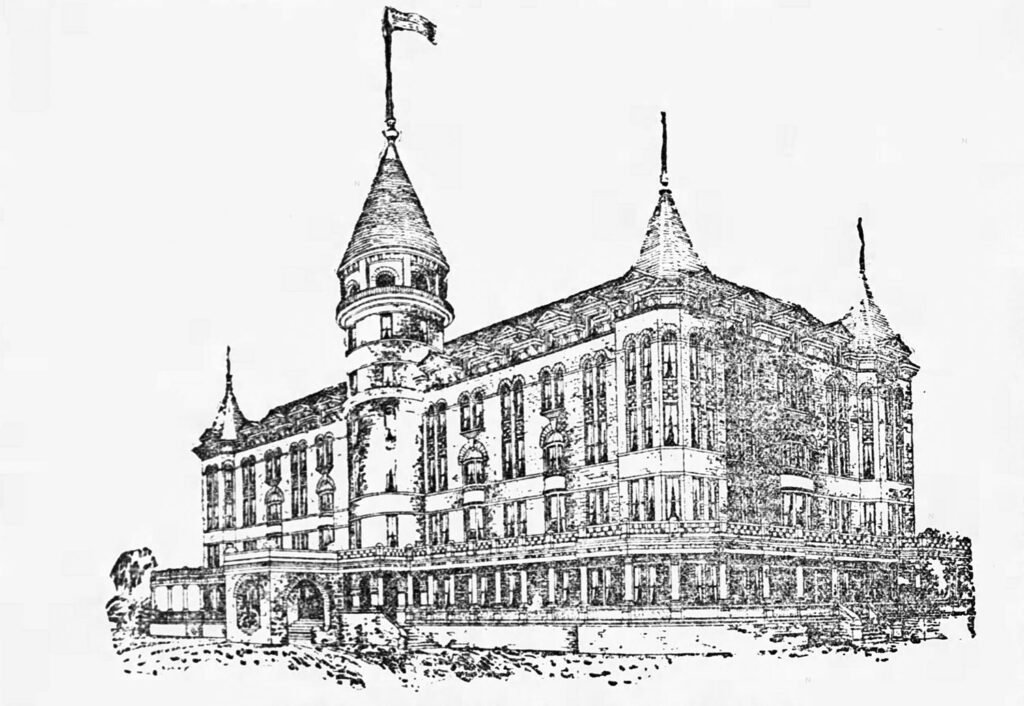

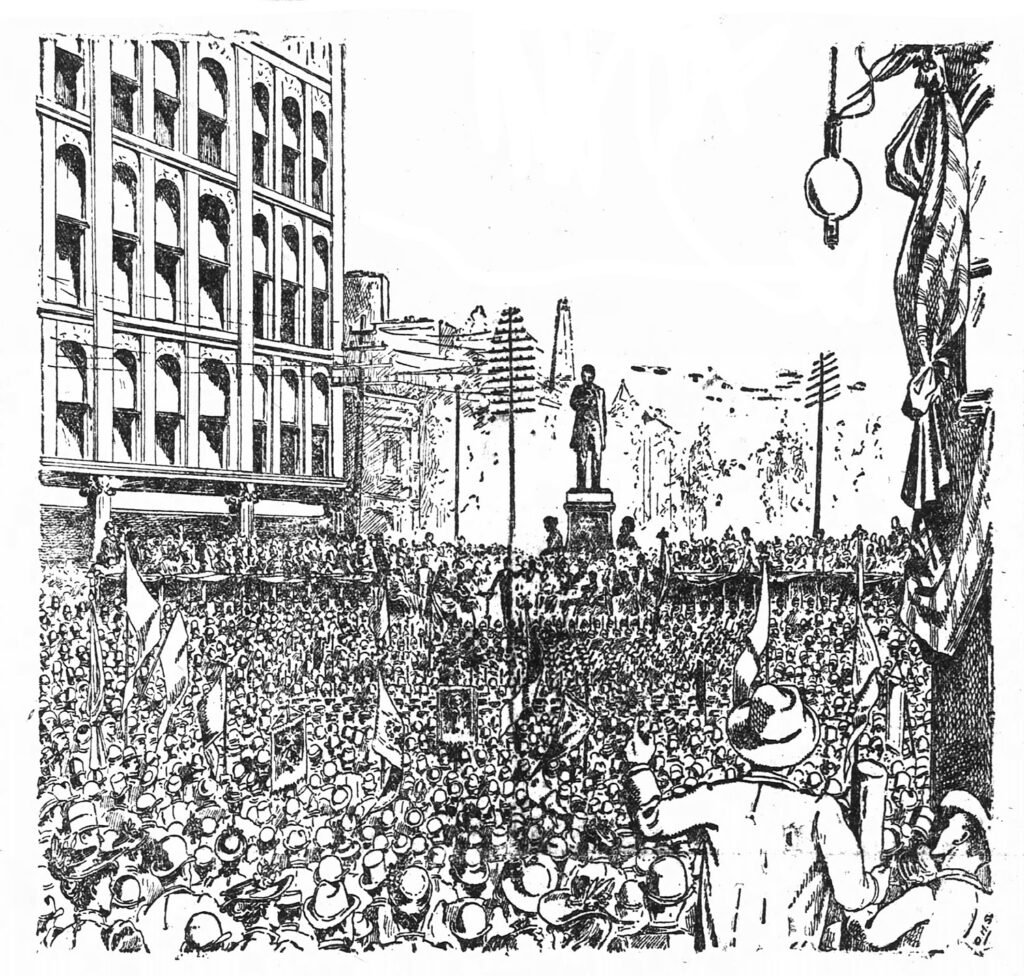

The Henry Grady monument was unveiled in a lavish public ceremony on October 21, 1891,4 which the Constitution predictably covered as if it were the event of the century, claiming that crowds in attendance ranged from 25,000 to 50,000 people,5 no doubt greatly exaggerated since the city’s population was less than 70,000 at the time.6

A monument to Grady wasn’t enough, however, and for decades the city slapped his name on various streets and buildings, including Grady Memorial Hospital and Grady High School in Midtown. The high school finally dropped his name in 2021,7 but the hospital remains “Grady”, and it’s hard to imagine a world in which Atlantans would ever call it anything else.

The Grady monument was erected at the intersection of Marietta and Forsyth Streets, and during the 1906 Atlanta race massacre, it served as an altar for the bodies of three Black men murdered by an angry white mob.

As the Constitution told the story:

One of the worst battles of the night was that which took place around the postoffice. Here the mob, yelling for blood, rushed upon a negro barber shop just across from the federal building.

“Get ’em. Get ’em all.” With this for their slogan, the crowd, armed with heavy clubs, canes, revolvers, several rifles, stones and weapons of every description, made a rush upon the negro barber shop. Those in the first line of the crowd made known their coming by throwing bricks and stones that went crashing through the windows and glass doors.

Hard upon these missiles rushed such a sea of angry men and boys as swept everything before them.

The two negro barbers working at their chairs made no effort to meet the mob. One man held up both his hands. A brick caught him in the face, and at the same time shots were fired. Both men fell to the floor. Still unsatisfied, the mob rushed into the barber shop, leaving the place a mass of ruins.

The bodies of both barbers were first kicked and then dragged from the place. Grabbing at their clothing, this was soon torn from them, many of the crowd taking these rags of shirts and clothing home as souvenirs or waving them above their heads to invite to further riot.

When dragged into the street, the faces of both barbers were terribly mutilated, while the floor of the shop was met with puddles of blood. On and on these bodies were dragged across the street to where the new building of the electric and gas company stands. In the alleyway leading by the side of this building the bodies were thrown together and left there.

At about this time another portion of the mob busied itself with one negro caught upon the streets. He was summarily treated. Felled with a single blow, shots were fired at the body until the crowd for its own safety called for a halt on this method, and yelled “Beat ’em up. Beat ’em up. You’ll kill good white men by shooting.”

By way of reply, the mob began beating the body of the negro, which was already far beyond any possibility of struggle or pain. Satisfied that the negro was dead, his body was thrown by the side of the two negro barbers and left there, the pile of three making a ghastly monument to the work of the night, and almost within the shadow of the monument of Henry W. Grady.

So much for the city too busy to hate.

The Grady statue still stands at the intersection of Marietta and Forsyth Streets in Downtown Atlanta, but it’s easy to overlook. In June 1996, it was moved 10 feet from its original spot for greater visibility,8 but it remains surrounded on both sides by a canyon of glass and steel buildings that casts the monument in near-constant shadow — that’s probably for the best.

When the statue was unveiled in 1891, W.W. Goodrich felt the need to offer his thoughts on the subject — because of course he did — with remarks to the Constitution that should be viewed with great skepticism, given his well-noted propensity for lying.

In the following article excerpt, Goodrich claims to have had “several conversations” with Grady — “in his sanctum,” no less –and acts as if the two men were intimate friends.

Let’s do some quick math here: Goodrich came to Atlanta in September 1889,9 and Grady died on December 23, 1889, after a month-long bout of pneumonia, during which time he also took extended trips to New York and Boston.10

Would a no-name newcomer from California have been able to engage in “several conversations” with Grady in under 3 months? I have serious doubts.

Here, Goodrich also compares Grady to Abraham Lincoln, with whom he was apparently quite enamored [see also: “The President and the Bootblack“], sharing an apocryphal tale about Lincoln that he undoubtedly pulled straight from his ass.

And on that note, we won’t be hearing much more of Goodrich’s bullshit for a while. Thank God.

Article Excerpt:

All during the day, and away into every night, there is a group around the Grady statue. Yesterday it was surrounded all day by men, women and children, who were studying the bronze figure. As late as 10 o’clock last night there were at least twenty people in front of the statue, gazing at it.

Mr. W.W. Goodrich, the architect, says:

Looking upon that face in living bronze, studying its points of character, the many thoughts of the several conversations I had with him pass in review before my memory. Shortly after making Atlanta my home, I called upon Mr. Grady in his sanctum. Always courteous, cordial, and painstaking in a marked degree, to make a stranger at home, in his beloved city, was he to every one. He never referred to the past, but that he predicted from out of it would arise in the south, in this favored region, the grandest lives of our future republic. He predicted that the mighty forces of science would hereabout establish those appliances of labor that would elevate the new south above her most rosy anticipations.

“And why not,” said Mr. Grady to me once, “about us all are the minerals, inexhaustible, that are used in manufacturing enterprises. Our fields give us the raw material for our spindles to manipulate, our firesides are aglow with fuel from nearabout, our food products can all be raised here, our climate cannot be excelled, our transportation facilities place us speedily in all the markets of the world. Again, the active hands behind all this are young men who were boys after the surrender. From bank presidents down to humble vocations, our young men are the leading spirits.”

And whilst I listened to the speeches of Mr. Clark Howell and his co-laborers, at the unveiling ceremonies last Wednesday, I could not help but think of Mr. Grady’s remarks: “Our young men are back of it all, and are the active hands in the forwarding of all this remarkable prosperity and progress.”

Atlanta is peculiarly a city of young men. Their influence is felt on every hand, in every vocation, trade or profession. The brainy young men are back of it all, of all this wonderful and real prosperity, of all this great progress, and the future greatness of our city can be ascribed to the young men. And Mr. Grady was a young man. His addresses show the fire of youth with the mannered culture of experience. The young men of the new south are her bone and sinew, the coming giants in the political arena. The star of empire, for solid practical government, that government of the people, for the people, and by the people, that government of genuine Americans for Americans, is here in the south. From my observation, I verily believe there is more Americanism in the south than in all the rest of the country put together; and more love of American institutions for what they have been, for what they are and for what they will be in the future.

Mr. Grady admired the character of Lincoln, and with emotion remarked that the south lost her best friend when Mr. Lincoln died. He stated that Washington and Lincoln were the two greatest men of the world. And Governor Hill, in his remarkable eulogy of Mr. Grady, at the unveiling ceremonies, likened Washington, Lincoln and Grady as the three greatest men of our country.

Having occasion to visit Philadelphia during the early part of the war, Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward were in a car with several distinguished confederate soldiers on parole. These gentlemen were personally known to Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward, and as they chatted together in a most cordial manner, one of the confederate officers said: “Mr. President, what think you of the war?” Grasping the subject instantly, Mr. Lincoln asked:

“General, what do you think of the old flag?” The general’s color instantly turned and he did, not answer. Rising from his seat across the aisle he paced up the car and back to Mr. Lincoln’s seat and finally replied: “Right there was the south’s mistake.” “Yes,” said Mr. Lincoln, “had the south come north with the old flag, there would have been no war.”

I asked Mr. Grady is he had ever heard of the above conversation. He said that he had from one of the generals who was with Mr. Lincoln at that time. He stated the general’s name, and this same general was a very prominent man in the confederacy, and also stated that Mr. Lincoln’s remark about the old flag, was the truth.

Referring to this conversation, at a subsequent interview, Mr. Grady said: “There as one distinct thought that occurs to me, and that is this, Mr. Lincoln was peculiarly a man of the masses, and not of the classes.” Mr. Grady was a man of the masses, and not of the classes, and therein he was like Mr. Lincoln. His strong position with the masses made his paper, The Constitution, to be read by untold thousands all over the country, who saw in the new south that future of prosperity and progress that was typical in Mr. Grady’s greatness of heart, and of which he was the prime mover and its unflinching champion.11

References

- Life and Labors of Henry W. Grady. Atlanta: H.C. Hudgins & Co. (1890), p. 186. ↩︎

- The Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 1891, p. 1. ↩︎

- “The Grady Monument”. The Atlanta Constitution, March 6, 1890, p. 3. ↩︎

- “In Living Bronze.” The Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 1891, pp. 1-2. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Biggest Cities in Georgia – 1890 Census Data ↩︎

- Midtown High School (Atlanta) – Wikipedia ↩︎

- “Grady Moved By Olympics”. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 14, 1996, p. E1. ↩︎

- “Comes Here to Live.” The Atlanta Constitution, September 18, 1889, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Henry Grady Dead!” The Atlanta Constitution, December 23, 1889, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Etched And Sketched.” The Atlanta Constitution, October 26, 1891, p. 4. ↩︎