The Background

This is the second in a series of 5 articles on home decoration written by L.B. Wheeler (1854-1899), an architect who practiced in Atlanta from 1883 to 1891. The articles were published in The Atlanta Constitution in December 1885 and January 1886.

Here, Wheeler charted the origin of residential halls to Anglo-Saxon living rooms and criticized their “modern offspring” of the 19th century: “long, narrow, uncomfortable stair choked strips of passage”, which he characterized as “depressing”.

His description of a well-arranged central hall with a fireplace, stairs, and seating surrounded by a cluster of smaller rooms was the “living hall” concept introduced by McKim, Mead & White of New York in the 1870s. A fine example is their stair hall from the Metcalfe House (pictured below), on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

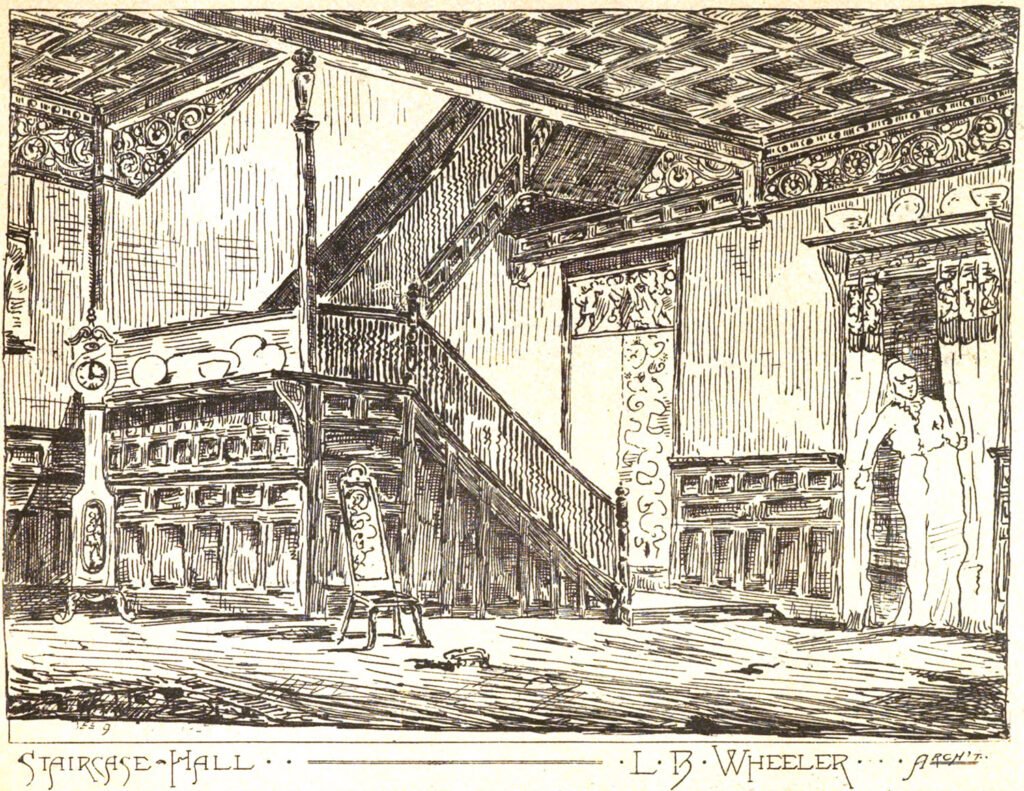

Having previously practiced in New York, Wheeler would have been very familiar with the living hall concept, as indicated by an 1882 illustration of a similar “staircase hall” he designed (pictured at top).

The concept was still quite new in Atlanta, however, likely introduced to the city by G.L. Norrman with his design for the Edward C. Peters House in 1883. By the end of the 1880s, pretty much every home of consequence in Atlanta had a large, fashionable hall as its nucleus.

In this article, Wheeler also took the opportunity to argue for the judicious use of stained glass windows, and admonished people who furnished their halls with uncomfortable seats for “errand boys and servants… suited to their condition in life…” Wheeler described such accommodations as “giving a stone when no bread was asked for…”

Spoken like a true New York radical.

Home Decoration.

Halls.

By L.B. Wheeler, Architect of the Kimball House.

December 13, 1885

The germ of our modern hall probably found its origin in the hall or living room of the Anglo Saxon. This hall was a large room with wooden walls and earthen floor in which lived, dined and caroused lord, lady, guest and serf alike, and where at night they lay down upon their straw filled sacks to sleep, arranged according to their rank. The only decorations of this room were the variously dyed and figured cloths hung upon the walls and against which, when not required for purposes of war and pillage, were frequently hung the arms and armor of its occupants.

The only furniture besides the chairs, which were for the exclusive convenience of those high in rank, were the benches, in which during the day were stored the beds used at night. The fireplace was the center of the room and the fire of logs, around which the shivering occupants gathered as the winds rattled the osier shutters and the rain beat upon the thatched roof and clay covered walls, poured forth constantly its curling wreaths of smoke which lingered loitering among the guests before ascending to the roof and taking a final leave of the dried meats and other stores, as it passed out at the gables.

Although not what would now be considered habitable the old saxon hall had an air of homeliness and hospitality about it which is seldom possessed by its modern offspring.

The hall, like the host, should greet you hospitably. What is more depressing than an introduction into one of the long, narrow, uncomfortable stair choked strips of passage, with rooms arranged in a row on either side, which, through modern courtesy is sometimes called hall, and which, whatever its width, is but a passage still? A well arranged hall is a great source of ventilation and heat, it should be a bond uniting the rooms in a complete and harmonious suite. The rooms so connected may be made much smaller than would otherwise be necessary, could not their dimensions, when occasion requires, be increased by uniting one with the other.

Halls are frequently used as sitting and reception rooms and when the floors are of hardwood are very serviceable for dancing. The furniture usually consists of a table, chairs, umbrella stand and hat rack, etc., all of which should be suited to their purposes, and not used for show. If you have no use for a piece of furniture, you may feel perfectly safe in rejecting it. Furniture is not made like pictures and statuary, to be looked at, but for use.

Hall chairs and seats should be comfortable. The necessity for this caution was suggested upon hearing a dealer in furniture explaining to one of his customers who had objected to a hall seat because it was uncomfortable. That it was for the service of errand boys and servants to whom we should offer in courtesy while awaiting our convenience a seat and temporary shelter from the inclemency of the weather and that such a seat should be suited to their condition in life and did not need to be comfortable. What kindness, what rare courtesy, that offers to the unfortunate under the guise of hospitality, aesthetic uncomfortableness, this is giving a stone when no bread was asked for. All that is necessary to make furniture comfortable and useful is a little thought expended upon its design. The staircase should be broad and ample with spacious landings, having short and easy flights leading in agreeable directions to the stories above. Upon this general arrangement of the staircase depends its effect, be it either of elegance, grandeur or inviting hospitality and no amount of unnatural twisting or torturing of rail or balusters or ludicrous imitation of massiveness or lavish display of cheap ornamentation can rectify a mistake originally made in this respect. Swans are not hatched from goose eggs; nor do lace and ribbons make an ugly form beautiful, although lace and ribbons may in their place be very attractive ornaments. The hall should be well lighted, not necessarily by stained glass windows. Nature seen through transparent plate or even crystal sheet is sometimes nearly as beautiful as stained glass. That this is not generally comprehended, is to be judged from the frequency with which we see really beautiful, natural scenery blotted out with much care and great cost by the use of those crude and violent contrasts of color so abundantly produced by some of our manufacturers. Stained glass, like jewels, should be used very sparingly, and unless, as with a picture, it is genuine art work, it had better not be used at all.

Its effects are so powerful that they challenge attention before everything else and if on inspection they fail to support their pretentions to consideration, the impression is very disappointing and likely to mold our opinion in regard to the remainder of the room and its contents. Of course it is unnecessary to state that a piece of coloring, which must necessarily be so powerful as that of stained glass, if used in any quantity, must become the key or point of cumulation of any composition in which it may be placed and should be suited to its position. It is well to assure ourselves before accepting our own judgment on these matters that we are not color blind. Many persons, who little suspect it are deficient in their perception of color and to produce an impression on them it is necessary to use some very striking combinations. The delicate and harmonies of one of Tiffany’s masterpieces, would not be perceptible to them. The eye usually requires considerable education before it is able to distinguish and appreciate delicate, refined and subtle combinations of color. The selection of stained glass should be left to a competent artist. As to the story or sentiment expressed and its fitness for its place, we may possibly be judges, but unless we have some special knowledge we had better suspend further judgment. The small sketches displayed by the agents of manufacturers are commonly no indication of the finished work. They are often made by parties who have nothing what ever to do with their execution. Stained glass, like any other art work, requires in its execution the application of the artist’s own powers.

Where it is desired in the arrangement of a suite of rooms that each should produced its proper effect upon the beholder, it is of importance that the best should be reserved for the last. The proof of the wisdom of this course may be drawn from our own personal experience.

After eating honey, sugar seems less sweet. One picture will destroy the effect of another. The skillful tradesman shows his best goods last, and after the loud rolling of thunder, even the lion’s roar seems mild.

Many people get too much thunder in their halls. Their principal idea of artistic composition being to arrange everything so that the beholder will be perfectly overcome upon his entrance into the hall; the result being that the hall overpowers and destroys the effect of every other room in the house and leaves none of those pleasant little surprises, which in a carefully studied design unfold themselves gradually to the interest and delight of the beholder.

If possible, a hall should have a fireplace–a good, generous and serviceable one–and in a pleasant and suitable position; not one of the little, narrow, useless things caged and squeezed into some remote place or corner, simply because its species are fashionable. Hall, home and fireplaces seem to be inseparable. How the very names kindle the imagination and sets memory wandering among her long forgotten stores, awakening pleasant reminiscences of long ago. An old house, moss-covered and gray, a sweep or road suddenly appearing beneath the hoary maples, guarding the decrepit gate, and as suddenly disappearing at the foot of the hill, only to be seen again in sudden flashes from behind mounds of green meadow and red and white farms, as it passes on to mingle in the gray confusion of distant meadow, farm and forest. And with it and a part of all the wind, which, sweet with the odor of the new fallen hay, flows gently up the hill and over the tangled grass of the lawn, enclosing the old house in its tender robe or coolness, penetrating every crevice, stealing in at the windows, and whispering to the lilacs and gooseberry bushes as it passes away, rustling secrets of the old hall within.

The old hall with its quaint mahogany staircase peeping out from behind the figured curtains, and leading away into the unfathomable mystery of tottling childhood. The oaken-timbered ceiling grown dark with age. The wainscoted walls, the generous fireplace, with its andirons of brass always so bright, and which in the long winter evenings were so serviceable, retaining in place the blazing forelog. The high shelf above the fireplace, and its brass candelabra, awakening with their prismatic reflectors strange fancies in the mind of imaginative youth, and over all the hospitable red chimney, which on Christmas day poured forth far above the misty gray trees its curling wreaths of welcome.3

References

- Tuthill, William B. Interiors and Interior Details. New York: William T. Comstock (1882), Plate 8. ↩︎

- McKim, Mead and White Stair Hall | The Metropolitan Museum of Art ↩︎

- Wheeler, L.B. “Home Decoration. Halls.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 13, 1885, p. 18. ↩︎