Americans are a bored and petulant lot of children who insist on living in an apocalyptic fever dream, always conjuring up some new monster to lash out at in dramatic spectacle, lest — God forbid — we attend to the darkness of our own souls.

Desperate to make a dollar, the news industry has long been willing to capitalize on our collective catastrophizing, constantly looking for the next shiny object to spin into a lightning rod for controversy. It’s not always successful, though.

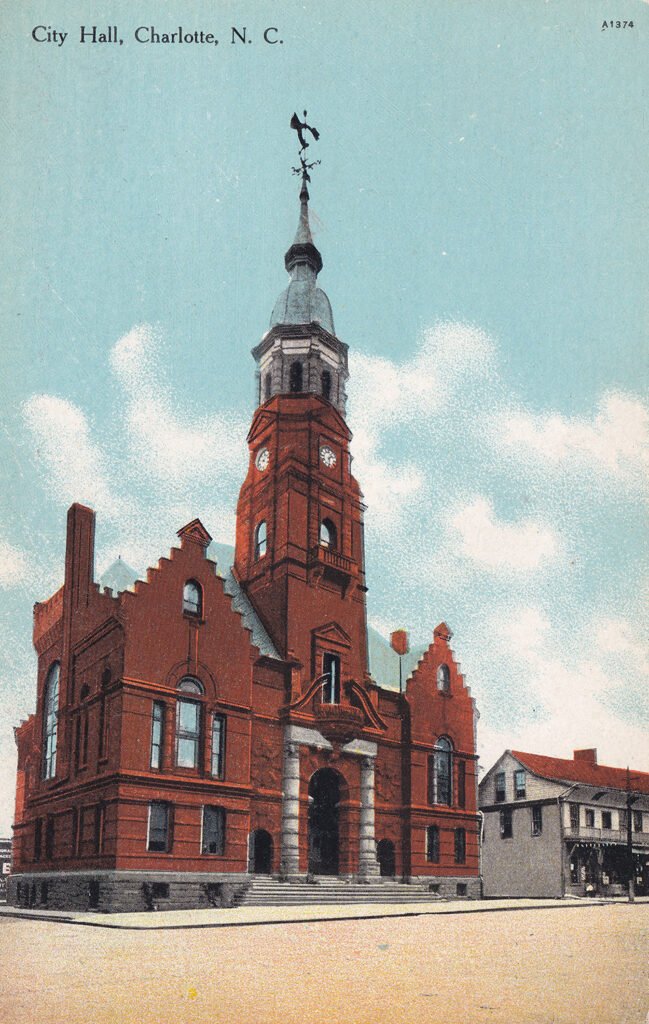

Such was the case in Charlotte, North Carolina, in 1892 and 1893, when the local press attempted to stir the public’s ire over a weather vane atop the new city hall, designed by G.L. Norrman.

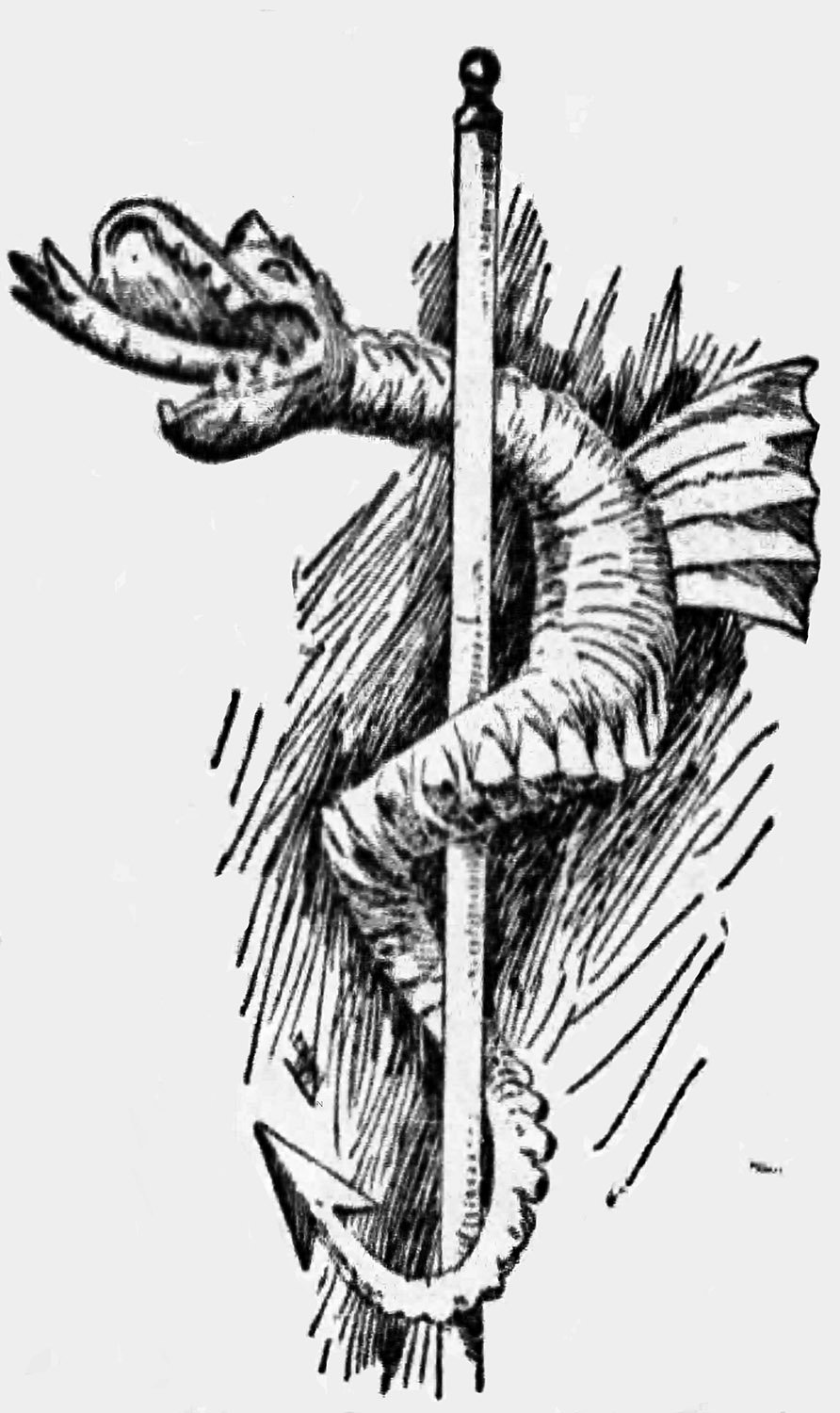

When construction on the building topped out in October 1892, it was festooned with a large tin weather vane shaped like a slithering mythical dragon.2 3

The Charlotte Observer was scathing in its assessment of the dragon, opining that “it may be classic, but not even its maker can say it’s pretty.”4 The paper added:

Yesterday afternoon after the monstrosity was placed, the universal query was “Why did they put such a looking thing up there?” The only answer that could be gotten was, “because the architect said so.” The mayor, nor any of the aldermen will own it; each declares he didn’t select it. But there’s no use in disapproving, the dragon has come to stay; may be it will improve on acquaintance.5

The dragon was designed by John Osborne, a Charlotte tinsmith, and Norrman reportedly pronounced it as “a work of genius”, claiming Osborne could get a position with him in Atlanta whenever he wanted. “It is hoped that this invitation includes the dragon,” the Observer cattily quipped.6

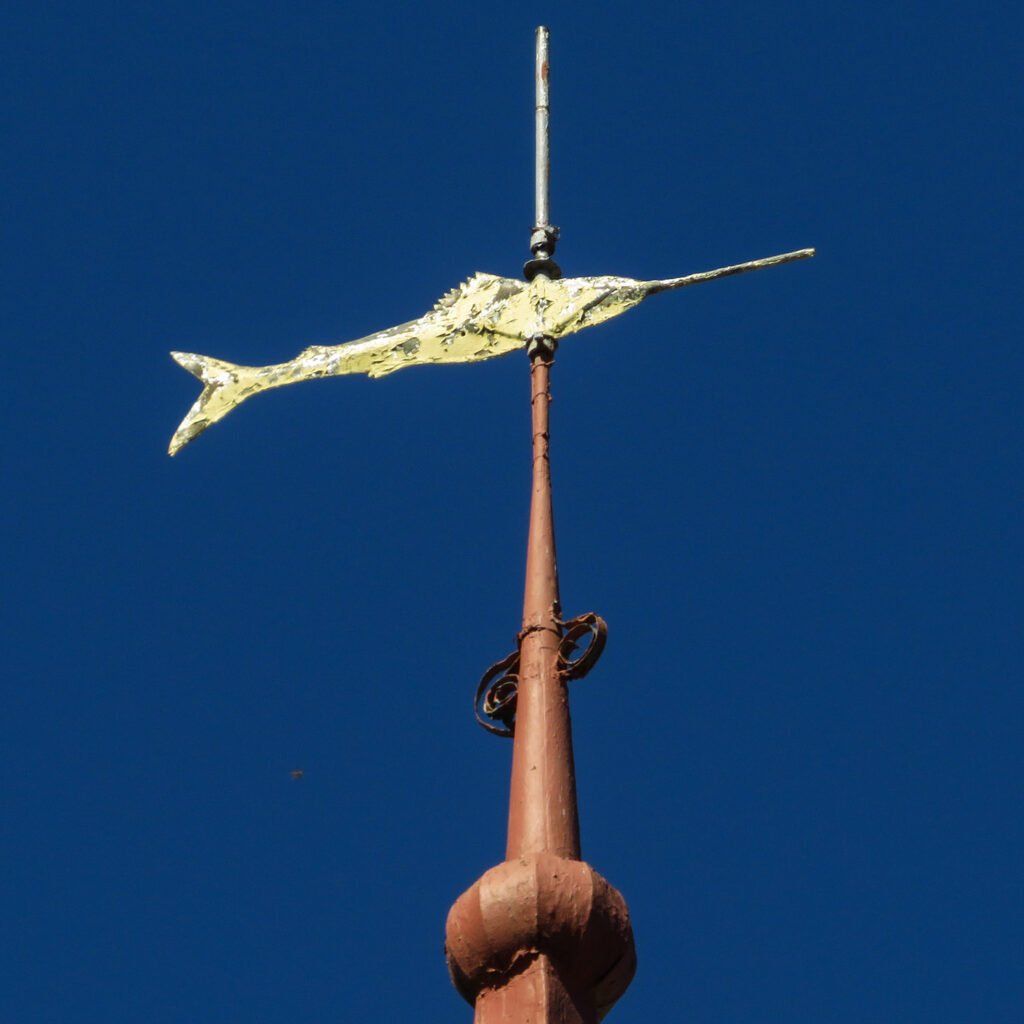

Norrman’s selection of the dragon no doubt stemmed from his fascination with Norse mythology, but he also had a history of adding mirthful creatures to his buildings. On the City Hall and Opera House in Newberry, South Carolina, for example, he topped the central tower with a weather vane in the shape of a garfish.

“Why this primordial and repulsive fish was chosen is not known”, a local historian later huffed — a touch overdramatic, I’d say.7 It’s also not known why local historians are so pompous and humorless, but that’s a discussion for another time.

A week after the dragon was placed on Charlotte’s city hall, a “Constant Reader” of the Observer anonymously wrote the following letter:

Can you kindly enlighten the public as to what the fiery dragon on top of the new city hall steeple is emblematic of? About the only reference the writer can find in regard to the dragon is found in the 20th chapter of Revelation and judging from what we read there it is not at all complimentary to the good people of Charlotte to be guarded over by a beast of that description. Why wouldn’t an American eagle or a hornets’ nest, for instance, be good enough for the Queen City?8

The newspaper responded: “The Observer‘s only answer to “Constant Reader’s” first interrogatory is that the design on top of the steeple is emblematic only of the way the work on the hall has drag(ged) on. Bang!”

It was a fair point: construction on Charlotte’s city hall began in December 18909 and was supposed to end in December 1891.10 However, the project was plagued by delays and was finally completed in April 1893.11

The Observer‘s campaign against the dragon was on a roll, and when Norrman visited Charlotte in November 1892 to check on the building’s progress, the newspaper couldn’t help but be disparaging:

Mr. Normann [sic], architect of the city hall, is here. He met with a cordial reception from the dragon–for he is its only friend. Mr. Normann says he is willing to take the dragon down if the people would prefer something else; but perhaps the dragon is a good safety valve; everyone can cuss it as much as he pleases, without fear of retaliation, and it is best for it to remain on high.12

Norrman’s offer to remove the dragon was unusually deferential and seemingly diffused the newspaper’s criticism, as it didn’t make another peep about the matter for weeks.

In December 1892, the Observer had apparently warmed to the dragon’s appearance, reporting: “The city hall tower shows up well from any direction around about the city–even the dragon looks handsome.”13

By March 1893, the Observer was clearly resigned to the dragon’s existence. In an article championing the work of the city’s mayor, R.J. Brevard, the writer proclaimed: ‘We can stand upon our city hall, beneath “that dragon” without fear, but pride, for we can say the hall and ‘dragon” are paid for…’14

In December 1893, the dragon was threatened by a zealous objector, although The Observer had nothing to say about the matter. Instead, The Charlotte News reported on the following incident from the annual conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church South that had just concluded in the city:

“…one large portly member sprung to the aisle and said: “It is time something were done. Even here in the city of Charlotte, the dragon, the image of the old devil himself sweeps around ‘with every wind that blows,’ from the top of the city hall. The country is on a gallop to the devil and let’s head it off.“15

The newspaper added: “It cannot be denied–the brother is right. The devil overlooks Charlotte.“16 Sensationalist much?

It seems nothing came of the impassioned threat, and the dragon remained on the city hall until the building was demolished in 1926 — the only Southern city that has destroyed its historic fabric more than Atlanta is Charlotte.

The exact date of the dragon’s demise was February 2, 1926, with The Charlotte News documenting its final dramatic moments:

The giant dragon, which once proudly flaunted its head to every whim of the weather, was a mass of twisted metal and steel at the foot of the tower. Piles of brick and stone were falling upon it in utter disregard of its former proud station high above the street.17

And thus ended the saga of Charlotte’s dastardly dragon, buried in a heap of rubble after 33 years.

References

- “The Dragon in Conference.” The Charlotte News (Charlotte, North Carolina), December 5, 1893, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Local Briefs.” The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), October 5, 1892, p. 4. ↩︎

- “The Dragon–It May Be Classic, But Is Not Pretty.” The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), October 7, 1892, p. 4. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “No restoration in foreseeable future for opera house”. The Index-Journal (Greenwood, South Carolina), February 10, 1983, p. 8. ↩︎

- “The Observer Has Solved the Riddle.” The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), October 15, 1892, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Local Ripples.” The Charlotte News (Charlotte, North Carolina), December 4, 1890, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Our New City Hall.” Charlotte Chronicle (Charlotte, North Carolina), November 29, 1890, p. 4. ↩︎

- The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), April 8, 1893, p. 4. ↩︎

- “A Pretty Little Theatre Could Be Made in the City Hall.” The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), November 1, 1892, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Local Briefs.” The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), December 2, 1892, p. 4. ↩︎

- “The Coming Municipal Election.” The Charlotte Observer (Charlotte, North Carolina), March 25, 1893, p. 4. ↩︎

- “The Dragon in Conference.” The Charlotte News (Charlotte, North Carolina), December 5, 1893, p. 1. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Falling Bricks at Old City Hall Menace Traffic”. The Charlotte News (Charlotte, North Carolina), February 2, 1926, p. 14. ↩︎