A masterpiece of the Brutalist style, the Whitney Museum of Art (1966) in New York was designed by Marcel Breuer (1902-1981), an American modernist architect of the 20th century.

Like so many architects of his era, Breuer’s legacy has been rapidly forgotten in the 21st century, with many of his buildings now under threat or destroyed.

Born in Hungary to a Jewish family, Breuer (pronounced Broy-er) was both a student and teacher at the Bauhaus in Germany, where he became known for his cutting-edge furniture designs, most famously the Wassily chair.

With the rise of the Nazi regime, Breuer moved to England in 1935, then immigrated to the United States in 1937 with his mentor, Walter Gropius, becoming a member of the influential Harvard Five group of architects.

Between 1938 and 1941, Gropius and Breuer designed several residential projects together before Breuer broke off and began his solo practice. One of their joint works is the Weizenblatt Duplex (1941) in Asheville, North Carolina, for which Breuer is credited as the primary designer.

Breuer’s architectural career is neatly bifurcated into 2 distinct periods that couldn’t be any less alike.

In the 1940s and 50s, he was chiefly a small-scale designer and specialized in the creation of light, airy International style residences that were much praised for their innovative floor plans and use of materials and building techniques.

In the 1960s and 70s, Breuer abruptly switched gears and almost exclusively produced larger and more lucrative corporate and civic projects in the forceful and imposing Brutalist style, using concrete as his primary material.

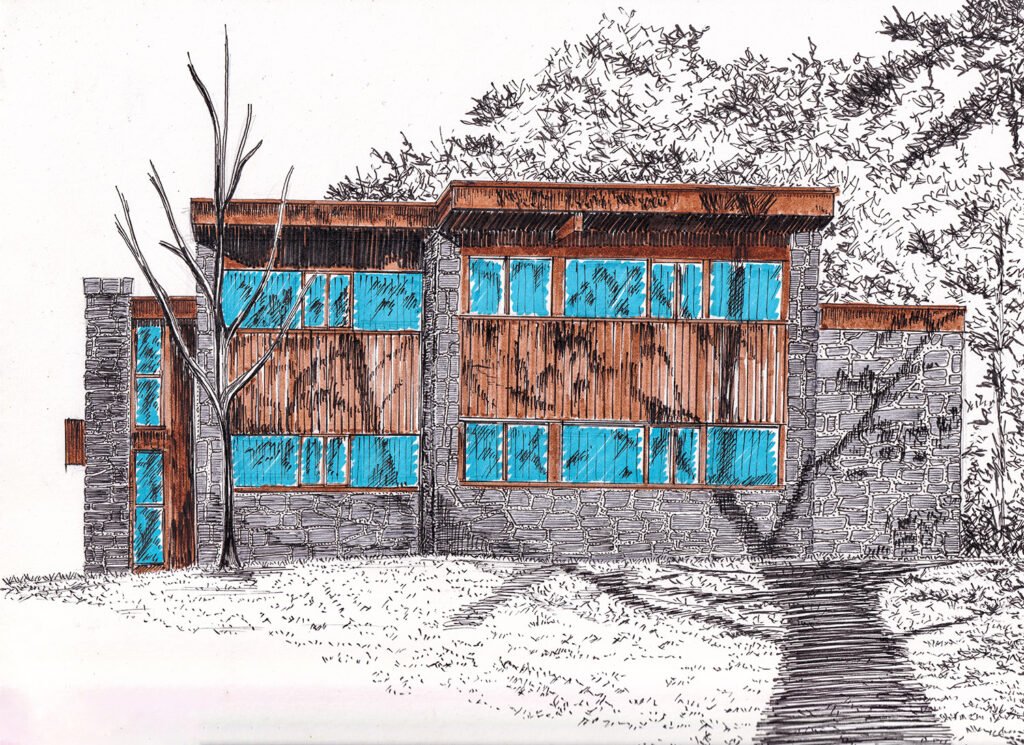

A typical design of Breuer’s residential period, the Snower House (1954) is also one of his least-known projects, occupying a large corner lot in the Mission Hills suburb of Kansas City.

The design is essentially a 1,800-square-foot rectangular box cantilevered on a concrete block base and was reportedly modeled after Breuer’s first home in New Canaan, Connecticut2, although most of his houses from the era had a similar look.

Breuer’s work was heavily concentrated in New England and the East Coast, and together with a house in Aspen, Colorado, the Snower house is one of only 2 completed residential projects he designed west of the Mississippi River3 — he never even visited the property.4

No one would claim the Snower house is one of Breuer’s better works, but it still has all the trademarks of his early residential designs. Notably, the home utilizes Breuer’s “bi-nuclear” floor plan, with living spaces placed on one side and sleeping areas on the other.

You can also clearly identify Breuer’s attention to form and creative use of materials: large windows on every side of the home blur the boundary between exterior and interior, tiny windows punctuate walls patterned in cedar strips, and brightly-colored asbestos panels add much-needed visual contrast.

The home has remained remarkably true to its initial design and, at the time of a 2015 article, had retained many of its original furnishings, including living and dining furniture designed or specified by Breuer, the original kitchen cabinets, and a built-in bookcase in the living room.

As of 2015, the interior still included the original cedar plank ceilings and walnut flooring, and the owners had restored the original orange, blue, and gold interior color scheme.5

The Snower house was built as a country residence, but is now surrounded by a sprawling maze of cookie-cutter homes. The structure spends most of the year concealed by trees, and with its cantilevered design, it almost appears to float among the greenery.

It’s a home that takes a certain amount of architectural knowledge to appreciate: while groundbreaking when it was constructed, today an uninformed observer could easily misjudge it as a holdover from a high-end trailer park.

Twelve years after the Snower house was built, Breuer’s design for the Whitney Museum of Art was completed at 945 Madison Avenue in New York’s Upper East Side.

Anyone unfamiliar with Breuer’s work would never guess the two projects were by the same architect, but look closely, and you’ll note that both buildings give the same suggestion of floating, and both show the same attention to form and materials.

Looking something like an inverted ziggurat, the 7-story, 76,830 square foot structure — now also known as the Breuer Building — was designed by Breuer with his longtime associate Hamilton P. Smith.

The building’s exterior is defined by cantilevered floors that progressively extend toward the street, covered in dark granite tiles over reinforced concrete. The ground floor entrance is set back from the street, accessed by a bridge spanning a moat-like sunken courtyard.

The facade presents a nearly blank face to Madison Avenue, apart from a large trapezoidal window, an element that became one of Breuer’s signatures. The north side of the building facing East 75th Street is punctuated by 6 smaller windows, similar to Breuer’s use of tiny windows in the Snower residence.

The building’s interior showcases Breuer’s ability to masterfully blend textures and patterns, particularly in the lobby and stairwells.

Smooth concave dome lights in the lobby contrast against the dark ceiling and roughly textured walls, created with vertical board-formed concrete. Floors throughout the building are covered in bluestone slab tile, and the walls in the stairwells are formed with bush-hammered concrete.

Sleek bronze railing on the stairs recalls Breuer’s earlier furniture designs, and the abundance of built-in seating thoughtfully incorporated throughout the building is an obvious byproduct of his residential period.

I visited 945 Madison in January 2024, when the building was about to end its 3-year run as the temporary home of the Frick Collection.

The Frick was a grim and joyless experience, and, for whatever reason, the museum’s management prohibited photography in the galleries — it’s not like any of their boring art was worth a picture. I dodged the leering security guards and snapped a photo anyway, because fuck that Nazi-inspired nonsense.

The Frick had covered Breuer’s signature windows with giant scrims, so there wasn’t much to admire in the building’s galleries. In the image below, you can still see some of the coffered ceilings, bluestone tiles, and built-in seating.

Breuer’s creative output arguably peaked with the Whitney and became increasingly repetitive and self-referential through the late 1960s.

In 1968, the same year he was awarded the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects, Breuer also faced severe backlash for his proposed Grand Central Tower, which called for the demolition of New York’s landmark train station, only a few years after the destruction of the original Penn Station ignited widespread protest.

New Yorkers aren’t known for forgiveness, and at Breuer’s death, Paul Goldberger, then the architecture critic for The New York Times, stated in his obituary for Breuer that the architect was “most likely to be remembered for things that are very small — things that are not buildings at all.”6

That observation was catty but dead on, as Breuer’s contributions to architecture are essentially unknown to the public today. And why is that?

Societal taste in architecture is always fickle, but the backlash against Brutalism has been especially swift and severe. What was initially embraced in the 1960s as a universal, egalitarian, and essentially optimistic style was, by the 21st century, widely viewed as hostile, oppressive, and just plain ugly.

It doesn’t help that concrete ages poorly: it cracks, it stains, and if it isn’t regularly power-washed (and it never is) it just looks drab and dirty. Slapping white paint on old concrete buildings has become popular in recent years, but it’s a cheap trick that never succeeds.

Breuer’s output was also wildly inconsistent in the second half of his career. While he had a few outstanding gems like the Whitney, his firm also produced a large number of banal and uninspired projects in the 1960s and 70s, with a clear prioritization for commissions over creativity.

Thus, Breuer’s name is associated with such dreary designs as the Department of Housing and Urban Development (1968) in Washington, D.C., or the downright hideous building for the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (1977) in the same city.

Later projects like the Strom Thurmond Office Building and Federal Courthouse (1979) in Columbia, South Carolina, shouldn’t even be mentioned in the same breath as Breuer, since he obviously had nothing to do with their design.

Breuer’s disappearance from public consciousness is also hardly unique: most people today are unfamiliar with his contemporaries like Philip Johnson, Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, or I.M. Pei, and the average person’s assessment of any of those designers’ best works would likely be unfavorable.

Breuer is still a favorite of architectural historians and preservationists, however, and they were outraged when Breuer’s first bi-nuclear residential design was demolished in January 2022 for the construction of a tennis court.

At the same time, Breuer’s own summer home (1949) in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, was also threatened with demolition but was spared with its purchase by a local historic trust.

In June 2025, the Department of Housing and Urban Development announced the departure from its Breuer-designed facility, and the future of that complex — which lacks historic protections — is anyone’s guess.

Some of Breuer’s projects have found new uses: in 2003, part of Breuer’s landmark design for the Armstrong Rubber Company (1966) in New Haven, Connecticut, was demolished for the construction of an IKEA store, but the remaining portion of the structure has since been converted to a boutique hotel.

Atlanta’s Central Library (1980) was the last project credited to Breuer, and it too faced possible destruction until it was spared by a controversial renovation completed in 2021. That story will be forthcoming.

References

- McCarter, Robert. Breuer. New York: Phaidon Press Limited (2016). ↩︎

- Billhartz Gregorian, Cynthia. “An original vision with an attention to detail”. The Kansas City Star, October 18, 2015, p. 20G. ↩︎

- McCarter, Robert. Breuer. New York: Phaidon Press Limited (2016). ↩︎

- Paul, Steve. “Architecture A to Z”. The Kansas City Star Magazine, April 18, 2010, p. 15. ↩︎

- Billhartz Gregorian, Cynthia. “An original vision with an attention to detail”. The Kansas City Star, October 18, 2015, p. 20G. ↩︎

- Burnett, W.C. “Architect Marcel Breuer’s influence memorialized in Atlanta Public Library”. The Atlanta Journal, July 8, 1981, p. 3-B. ↩︎