It’s astounding that I’m still discovering works designed by G. L. Norrman, decades after I first began looking for them. Just this week, another one revealed itself, bringing my total count of Norrman’s projects to about 425.

In an article from the February 6, 1927, issue of The Spartanburg Herald, the author recounted the history of the Kennedy Free Library in Spartanburg, South Carolina. The library’s first building was completed in 1885 — “Norman was the architect“, the writer casually notes.2

As Norrman practiced in Spartanburg between 1878 and 1881, and continued to return there for work throughout his career, “Norman” undoubtedly refers to him.

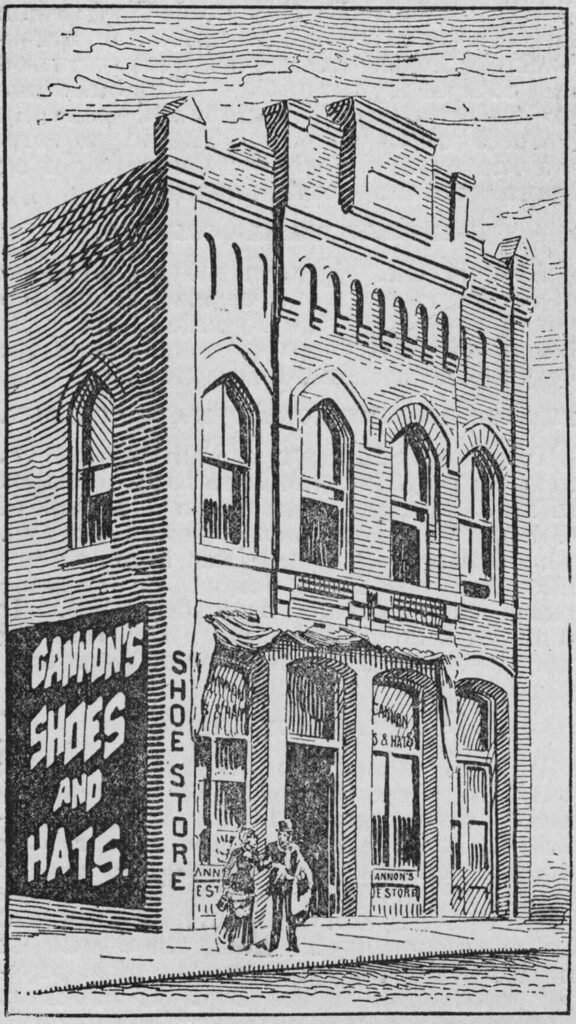

The above illustration shows the 2-story building, which was located just off the northeast corner of Spartanburg’s public square on a short street initially named Kennedy Place, and later Dunbar Street.

A Sanborn fire insurance map from 1888 indicates that the library was housed on the second floor, with retail space on the first,3 confirmed by the shoe store advertised in the illustration.

The building intrigues me for several reasons:

- It’s a rare example of Norrman incorporating Gothic styling in one of his designs, which it appears he largely disfavored, even for churches and school buildings. In a 1892 interview, he stated: “I prefer the classic for libraries…”

- The building’s cornerstone was laid in June 1883, a full 2 years after Norrman relocated from Spartanburg to Atlanta in April 1881,4 5 allegedly because he was upset by the “cheap construction” of his Spartan Inn project.6 Although Norrman owed the bulk of his professional success to Atlanta, I suspect his heart always belonged to Spartanburg: he maintained lifelong friendships in the town, and it was there where he became a United States citizen (his naturalization papers were still held there in 1909).7 Norrman must have visited South Carolina in 1882, when the Newberry Opera House was completed, and there were multiple residences in Spartanburg built between 1882 and 1884 (all demolished) that appear to have been his designs. This discovery adds further evidence that Norrman never entirely abandoned the Upcountry.

- Norrman didn’t truly come into his own as a designer until his 1886 plan for the W.W. Duncan Residence — fittingly, also located in Spartanburg. Anything from what I consider Norrman’s juvenilia period (1876-1885) is interesting because very little of it is immediately recognizable as his work, unlike most of his projects from the late 1880s onwards. I’ve seen the library illustration many times before, but never considered that he designed the building.

- The library’s appearance shared some similarities with another building in Spartanburg that I have long suspected may be of Norrman’s design, although I can’t find conclusive proof. The building at 154-156 West Main Street (pictured below) was built in 18828 and is notable for the quirky little Second Empire-style cupola on its roof. It’s just a hunch.

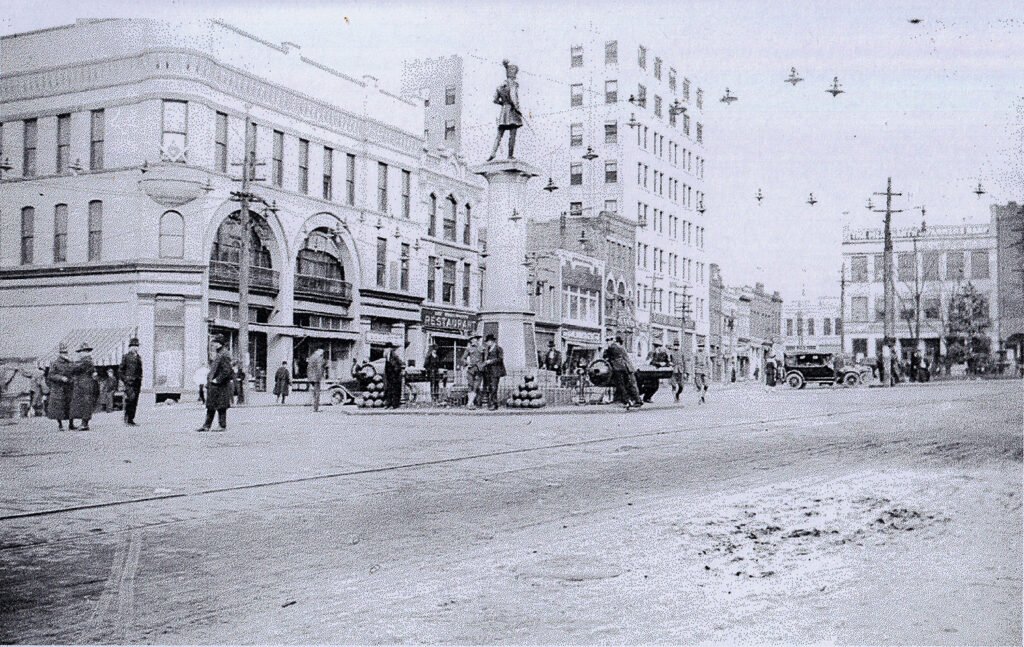

As it stands, the only extant store building in Spartanburg that I feel confident attributing to Norrman is the unremarkable structure at 101 East Main Street (pictured below).

The building was originally one-half of a block of 2 adjoining storerooms and is likely a project designed by Norrman for A.G. Owens of Mississippi in 1879.9 The neighboring space was later gutted by fire, although its facade (not original) is intact, and the remaining half has been significantly altered.

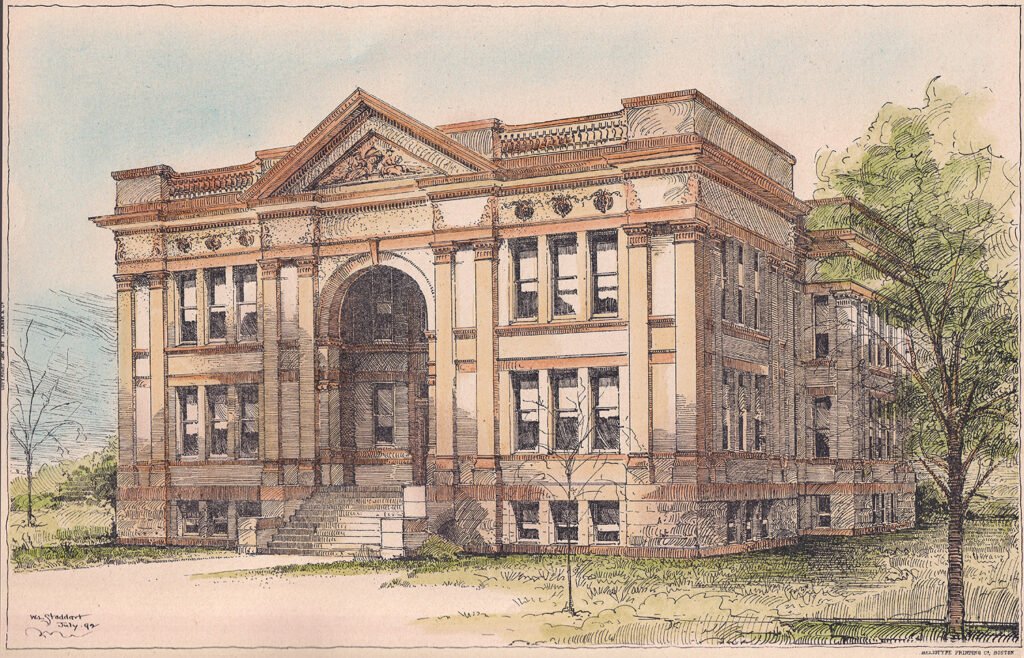

It appears the 1885 building that housed the Kennedy Free Library was demolished in 1974 for the widening of Dunbar Street,10 11 12 one year before the demolition of the nearby Duncan Building13 (pictured below), which Norrman designed14 in 1891.15

Both structures were victims of Spartanburg’s attempt to convert its downtown into a “mall”, following a plan by Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill that called for the creation of one-way streets and the wholesale demolition of historic buildings to lure savvy shoppers back to a modernized central core.16

As with the hundreds of other U.S. cities that “malled” their downtowns in the 1970s, Spartanburg’s effort was an abject failure,17 and a planned 15-story hotel and civic center complex that was to be built on the “Opportunity Block” that included both the library and Duncan Building failed to materialize.18

And thus does America continue to destroy itself: through arrogant plans and empty promises.

References

- Illustration credit: A Story of Spartan Push: The Greatest Manufacturing Centre in the South. Spartanburg, South Carolina, and its Resources. Spartanburg, South Carolina: The News and Courier (July 28, 1890), p. 52. ↩︎

- Mims, Julius. “Kennedy Library Improves Present Cataloging System”. The Spartanburg Herald (Spartanburg, South Carolina), February 6, 1927, p. 17. ↩︎

- Spartanburg, 1888 January – Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of South Carolina ↩︎

- “Messrs. Norrman & Weed.” The Atlanta Constitution, April 12, 1881, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Various and all About.” The Newberry Herald (Newberry, South Carolina), May 4, 1881, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Converse To Show Fruits Of Recent Funds Campaign”. Spartanburg Herald-Journal, October 6, 1957, p. A4. ↩︎

- “Prominent Architect Here.” The Spartanburg Herald, September 30, 1909, p. 8. ↩︎

- National Register of Historic Places — Nomination Form: Spartanburg Historic District ↩︎

- “More Improvements Contemplated.” The Spartanburg Herald, January 29, 1879, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Dunbar Street Demolition Is Next In Mall Progress”. The Spartanburg Herald, June 12, 1974, p. B1. ↩︎

- “Another Move In City Redevelopment”. The Spartanburg Herald, July 30, 1974, p. A9. ↩︎

- “This View From On Top Shows The Shape Of Things To Come”. Spartanburg Herald-Journal, August 3, 1974, p. B1. ↩︎

- Dalhouse, Debbie. “Opportunity Block Demolition Begins”. The Spartanburg Herald (Spartanburg, South Carolina), September 16, 1975, p. A1. ↩︎

- “Former Spartan Commits Suicide”. The Journal (Spartanburg, South Carolina), November 17, 1909, p. 1. ↩︎

- Racine, Philip N. Spartanburg County: A Pictorial History. Virginia Beach, Virginia: The Donning Company/Publishers (1980), p. 62. ↩︎

- “Spartanburg’s Downtown Mall”. The Spartanburg Herald-Journal (Spartanburg, South Carolina), March 2, 1974, p. C1. ↩︎

- Shook, Lynn. “Main Street Mall May See Traffic Again.” Spartanburg Herald-Journal (Spartanburg, South Carolina), August 30, 1984, p. A1. ↩︎

- Smith, Adam C. “Spartanburg back at drawing board”. Spartanburg Herald-Journal, July 28, 1991. p. B1. ↩︎