The Background

The following article was published in The Southern Architect in 1893 and written by W.W. Goodrich, an architect who practiced in Atlanta between 1889 and 1895.

The Southern Architect was a monthly trade journal conceived and initially published by Thomas H. Morgan of Bruce & Morgan, patterned after national architectural publications like The American Architect, which gave scant coverage to work in the Southeast, likely because the region’s architecture was — on the whole — terrible.

Speaking to an audience of his peers, Goodrich echoes many familiar complaints shared by professional architects in the late 1800s, when the industry was almost entirely unregulated, and any builder, carpenter, or cabinet-maker could call themselves an architect, copy a building plan from a pattern book, and pass it off as their own.

In a region as vainglorious as the Deep South, where the appearance of wealth and the illusion of status have long been valued over character and substance, the grotesque and excessive designs of substandard architects in the 19th century were not only admired but prized.

Here, Goodrich places the blame for bad architecture squarely on the clients, mocking the poor taste and ludicrous sense of entitlement that have always defined the newly monied. And although he specifically avoids mention of Atlanta (“Every city is cursed with it”, he notes), surely his chief inspiration was the city’s insufferable nouveau riche — and really, there is no other riche in Atlanta.

At the time of this article’s publication, Goodrich’s practice in Atlanta was waning, and he’d no doubt experienced his fill of the city’s empty boasting and repellent arrogance — although he was pretty full of shit himself.

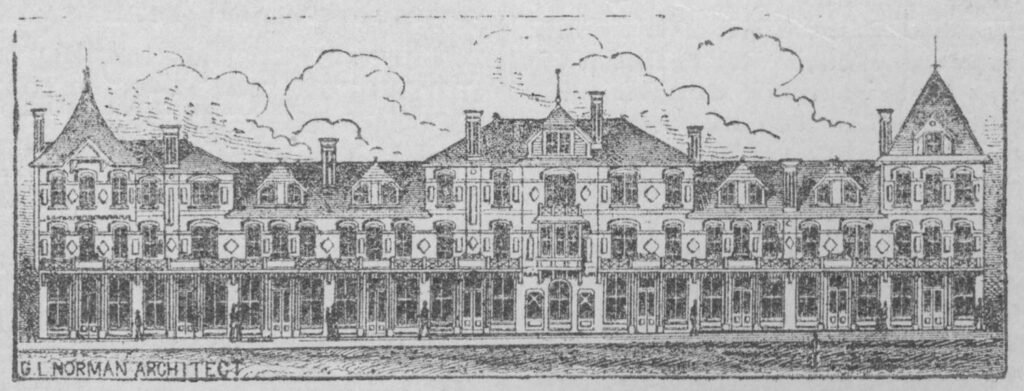

Goodrich’s acerbic, cutting language in this article contrasts sharply with the facile, fawning tone he affected in earlier articles for The Atlanta Journal, more closely resembling the embittered words of another Atlanta architect, G.L. Norrman.

Indeed, the picture painted by Goodrich is bleak: The legitimate architect is resigned to tossing his ideas in the trash, while “Mr. Newrich” demands “another incongruous architectural absurdity that the architect is not responsible for, and should not be blamed for.”

And thus is Atlanta architecture in a nutshell.

Incongruities of Modern Architecture.

There are no incongruities in the designs of modern architects, no fallacious fancies. In writing about modern architects I mean those only who are genuine members of the profession; “Educated for the Profession.” I do not include any one in the noble profession of architecture who is an architect and builder – or one who furnishes designs from books and periodicals.

That there are incongruities in the designs and in the buildings of the so-called “architects and builders” goes without question.

Shameful examples are on every hand of the “architect and builder’s” botch work.

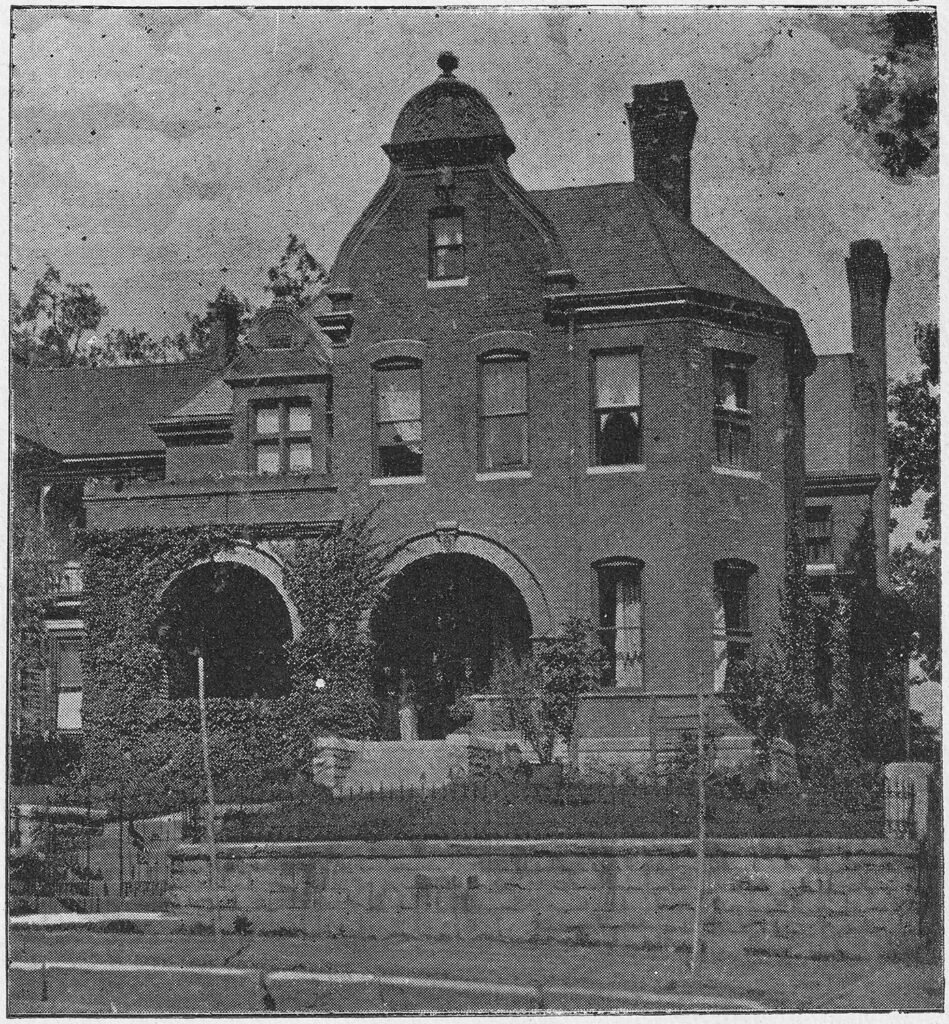

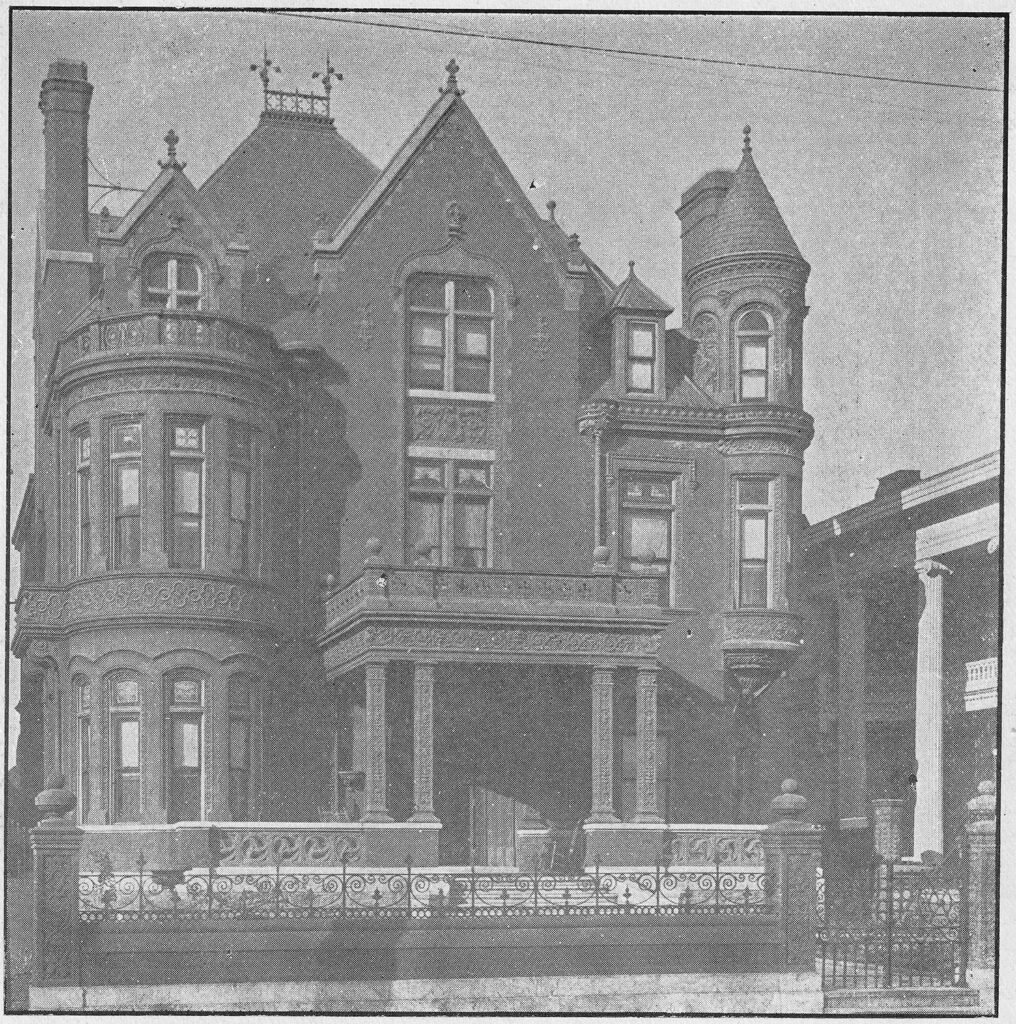

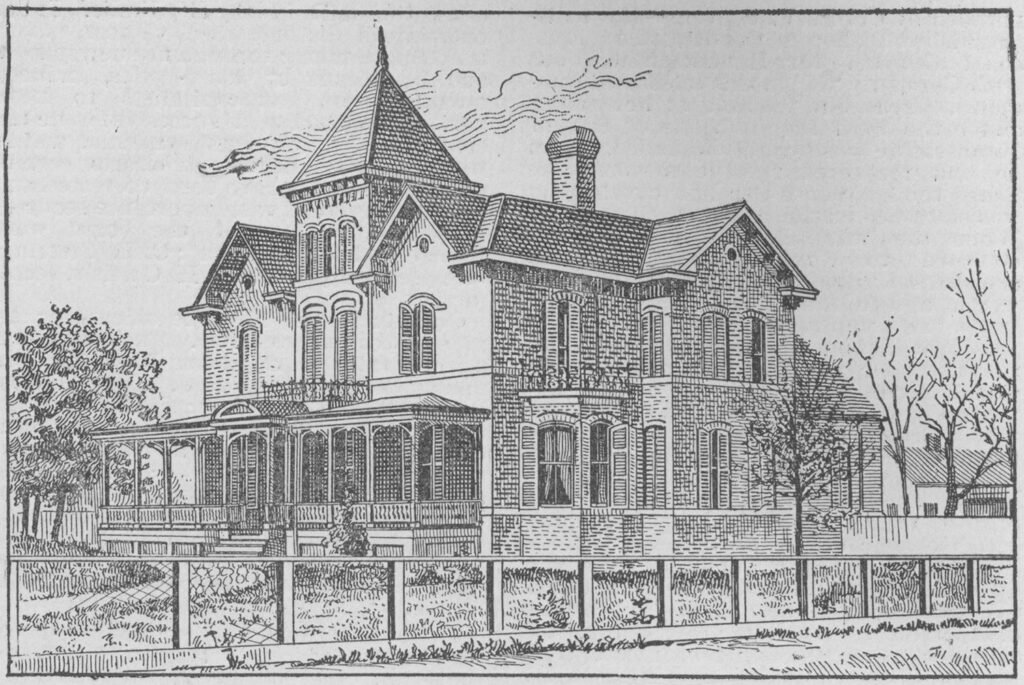

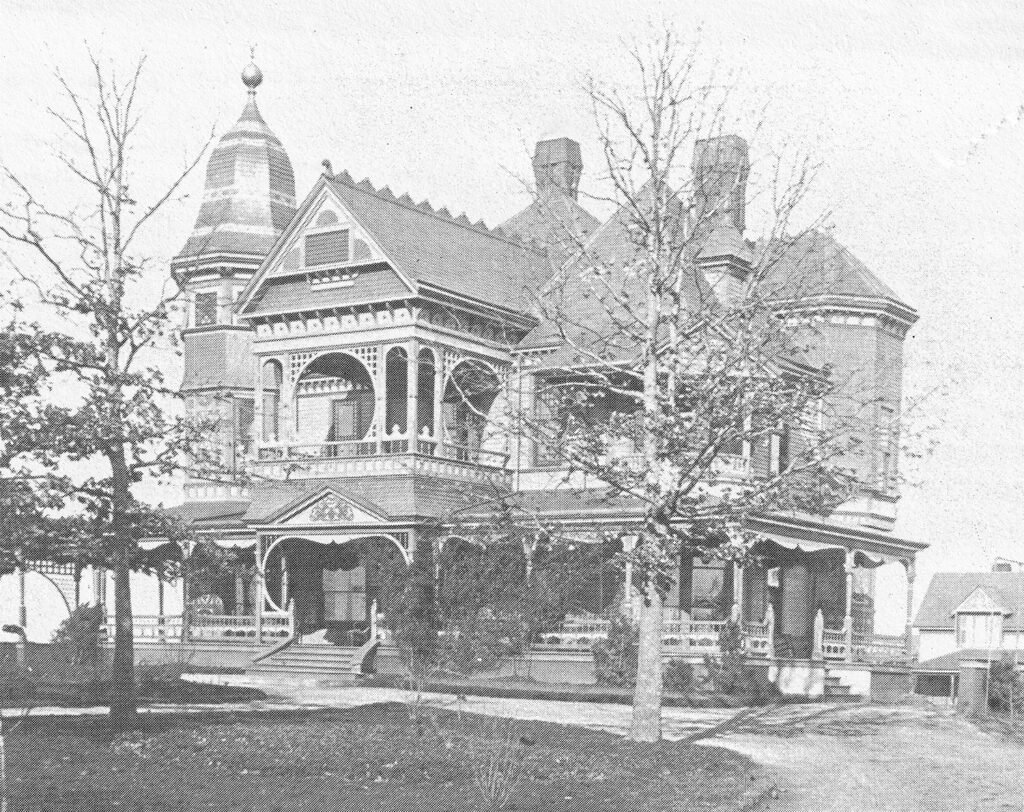

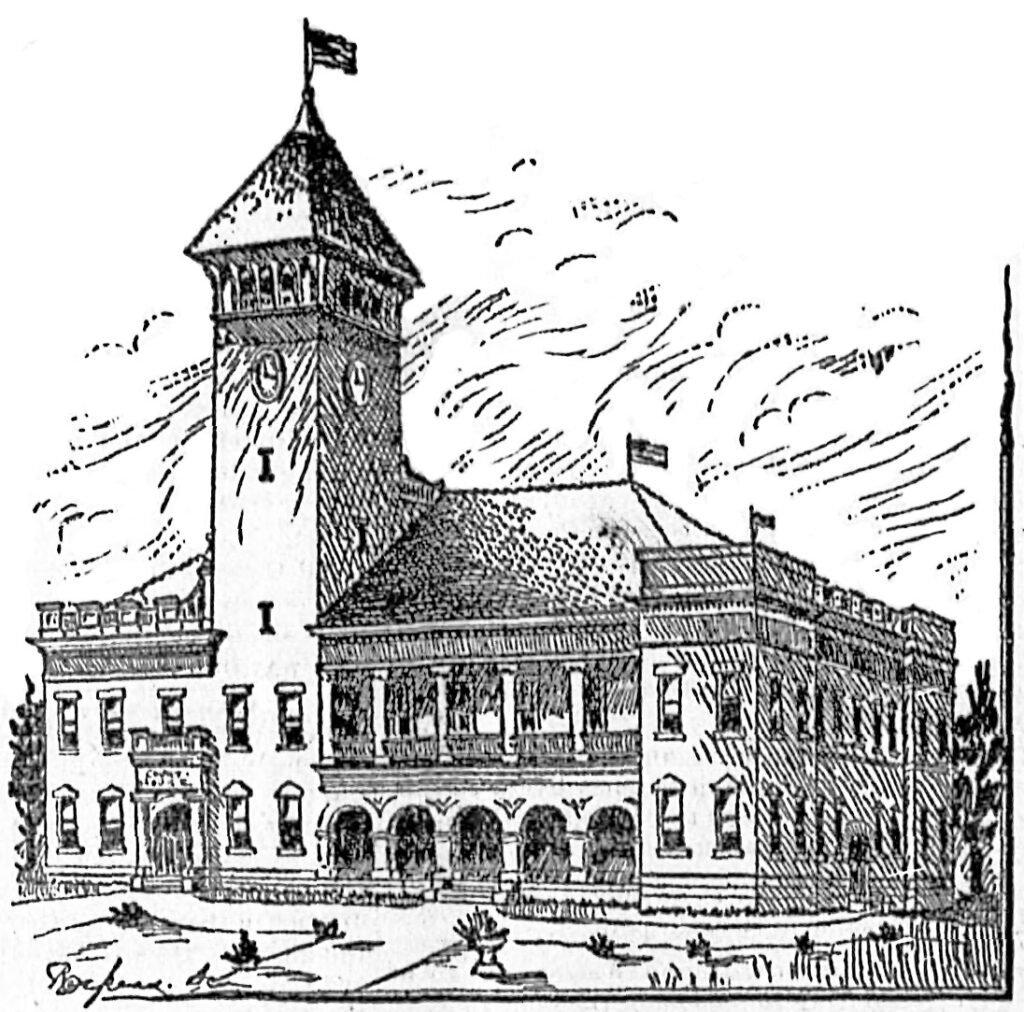

Every city is cursed with it, glaring at the observer at every turn. Any one can detect the carpenter or mason architect. The carpenter architect puts on his facades all the turned work, all the scroll work, all the ornamental work, so-called, that he can possibly get on, i.e., gingerbread work. He will put on domes in unheard of places, towers that look like pigeon houses or children’s playhouses perched upon a roof, straddle of a ridge, or perched in a valley, and in out of the way places.

Any ornamentation that his untutored mind imagines is to him a work of art, and readily finds a resting place on his buildings. An utter lack of harmony, of symmetry and of sympathy is in all his work from cellar to attic, while the real architect is blamed for the unprofessional hideousness of the wood butcher.

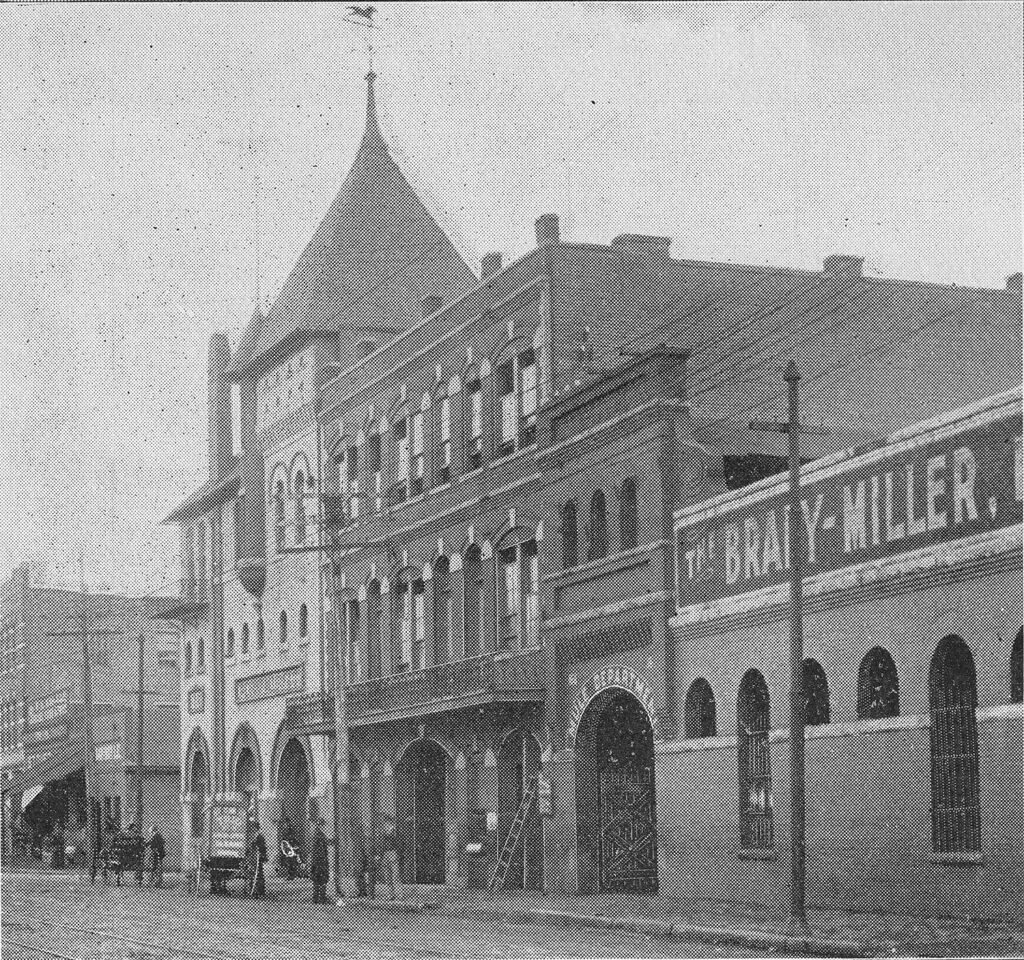

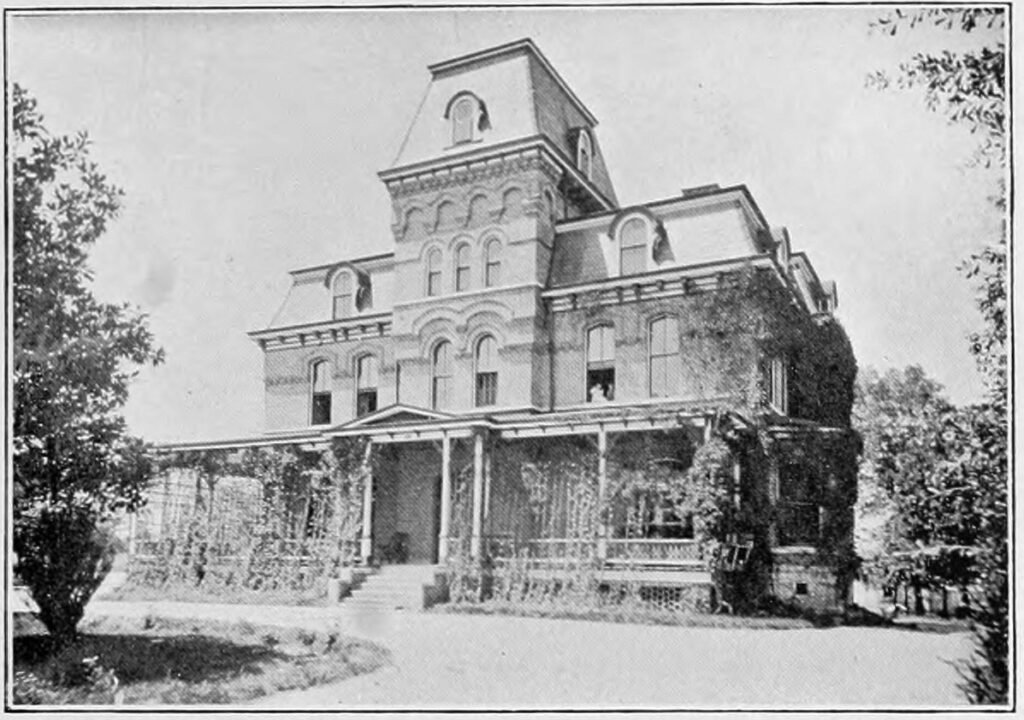

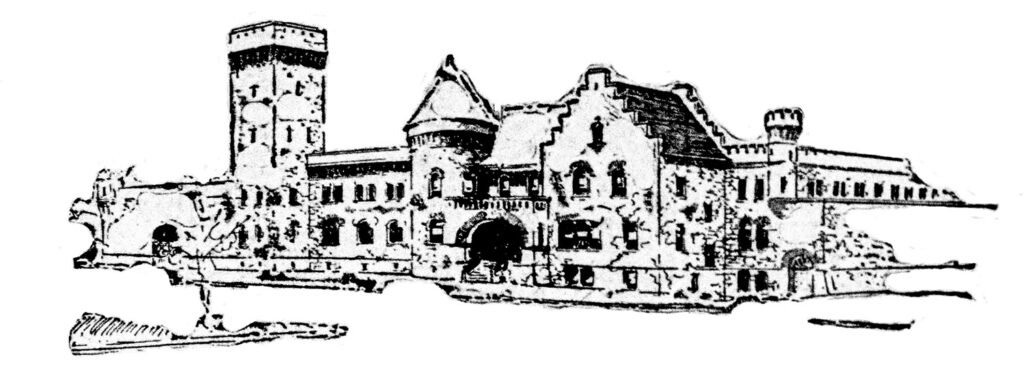

The mason architect runs riot on arches that will not carry the load and the thrust flattens them so that they fall by their own weight; arches that gravitate to the ground.

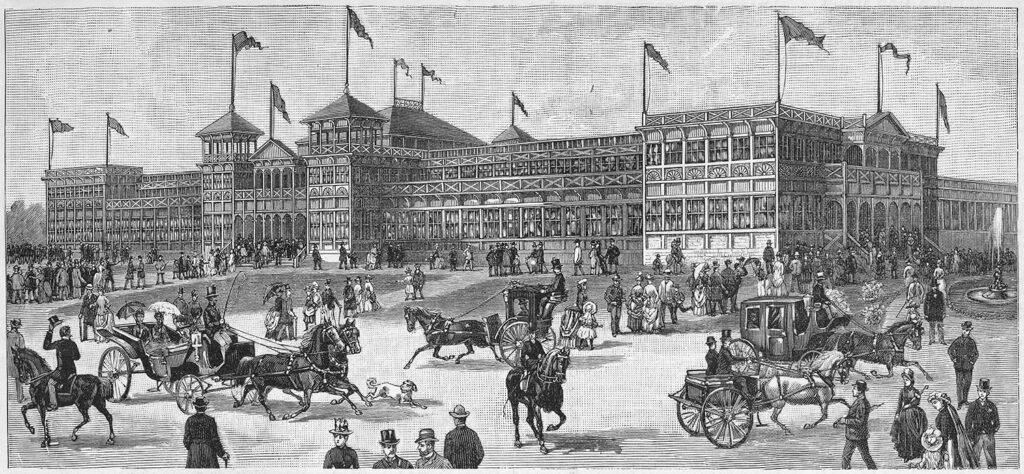

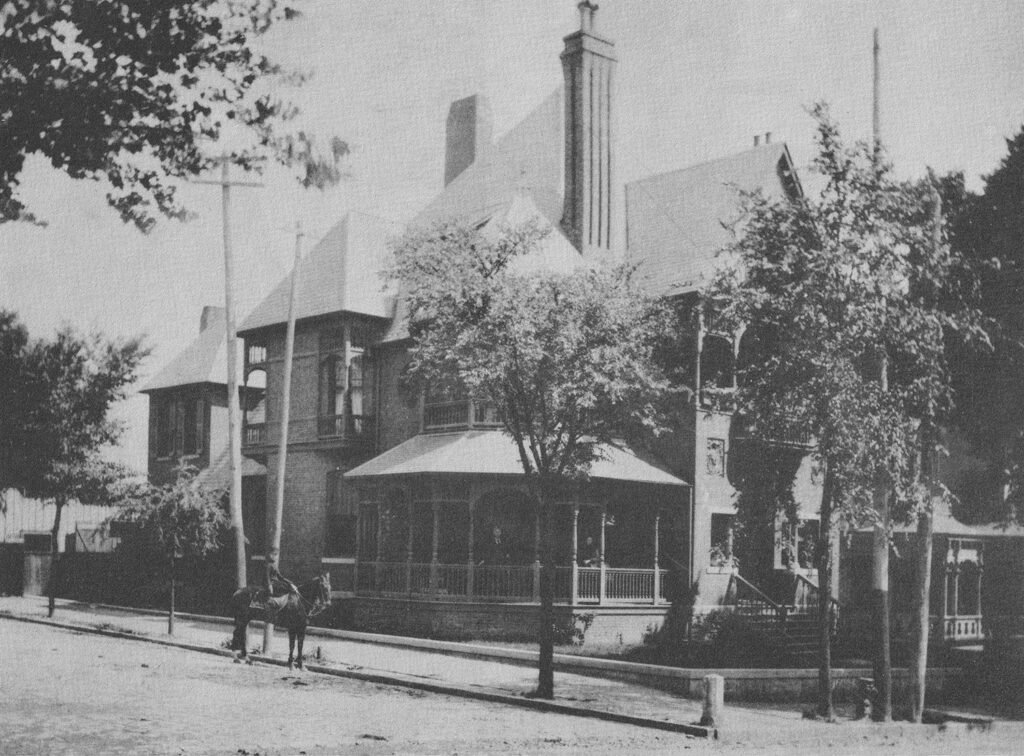

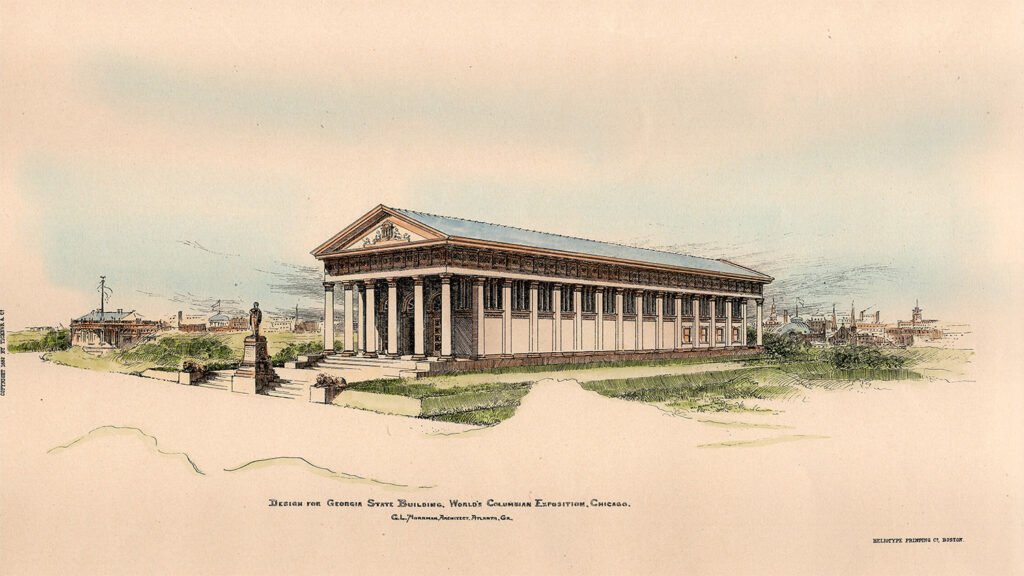

Then there is the civil engineer who sets himself up as an architect without any architectural study whatever. His designs and buildings look like railroad roundhouses or car shops, massive as the pyramids.

I admit the foundation of architecture, “the science of construction,” is engineering, but I do not admit that the ornamental, the harmony of detail, the grouping of mass, the blending of the line between earth and sky is engineering. “It is the music of the soul,” that infinite inspiration of the imagination, that looks in and through all that is beautiful and weaves the warp and woof of the soul’s fancy into a creation; that compels all to know that a master brain has left the imprints of a genius, of a glorious creation, that is a monument for all time to come. To inspiration this creation is simplicity itself, quiet dignity in material, color, form and construction. “A babe can comprehend it.” The simple vine, the color of the lily, the structural construction of canes, the grouping of mass, where weight is required to be sustained, these are the interesting points of the study of the architect.

He does not look after false effects to incorporate them into his building. He avoids them, he shuns them. His whole ambition is to blend his material that the effect shall be an architectural symphony at once attractive but not false, in the which the object is subservient to the client’s demand and the cash account used to the best advantage, so that there shall be no waste.

Clients are solely to blame for all the incongruities of modern architecture, in nearly every instance.

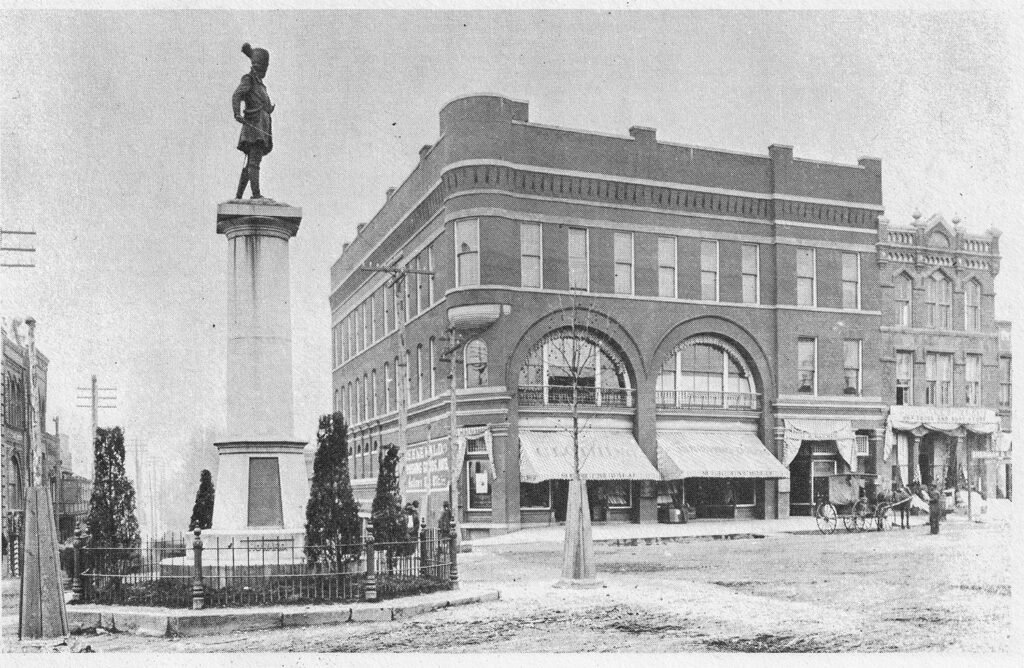

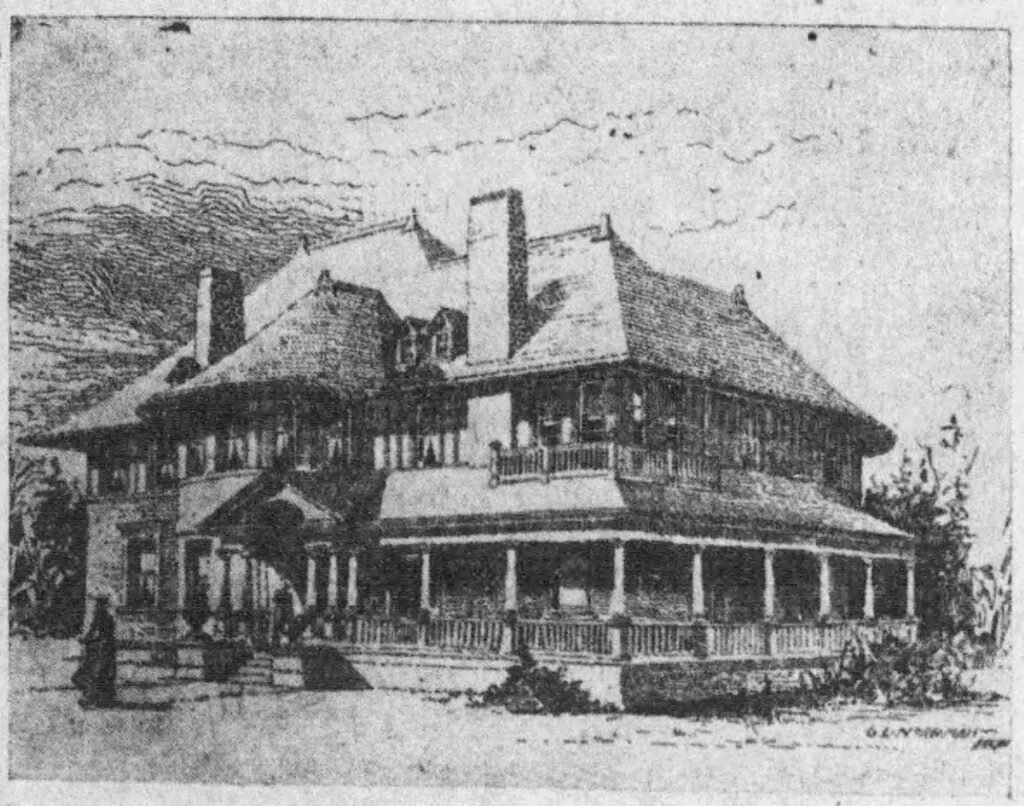

Mr. Newrich or Mrs. Struckile wants a home. It must excel in sublimity the palaces of the world; it must be the most picturesque and distinguished home in the city; the most exquisite charm of the avenue. Mr. T. Square is called upon for designs. He is recognized as an expert and a gentleman of large experience, thoroughly up in his profession. His charges are the regular institute ones, “which all gentlemen should adhere to” without exception.

The newly rich client says: I want so and so – it is my taste; I want my plan like this; at which Mr. T. Square, with his keen discernment of men and things from long practice with an extensive clientele, and with an eye to the etiquette of his most noble calling, says, such and such things won’t work out, won’t harmonize, are not in good taste, are of bad form, and won’t make a pleasing whole, and will be exceedingly incongruous. And he shows the client the utter lack of sense in the client’s demands and wishes, “of course in a gentlemanly way.”

“But, Mr. T. Square, it is my money that pays for what I want, and if you won’t work up my ideas and build as I want, I can get some one that will.”

Poor Mr. T. Square; his professional standing conflicts with his bread and butter; he hates to create a botch, yet his family must have bread; either lose the job, or do work that his very sensitive soul shrinks from touching because he knows that he is and will be held responsible for an incongruous blemish on his architectural escutcheon.

His ability is unquestioned, his record is proof against all vilification, but if he erects the building he will be held responsible for an architectural monstrosity, an incongruous mass. Alas! Others will do it if he won’t, and he quietly puts his views in the wastebasket and is dictated to by Mr. Newrich, and the consequences are another incongruous architectural absurdity that the architect is not responsible for, and should not be blamed for.

W.W. Goodrich2

References

- “Kennesaw Mountain.” The Atlanta Journal, February 4, 1892, p. 5. ↩︎

- Goodrich, W.W. The Southern Architect , Vol. 4, no. 11 (September 1983), p. 317. ↩︎