The Background

This is the final installment in a series of articles published by The Atlanta Journal in 1898 featuring illustrations and floor plans of residences designed by Atlanta architects — or, in this case, a contractor.

The Journal was clearly scraping the bottom of the barrel here, unless the intent was to caution readers against hiring an illegitimate architect. The article highlighted the J.B. Hightower Residence, located at 55 Hurt Street1 in Atlanta’s Inman Park neighborhood, and “done” by a local contractor, E.T. Gibbs.

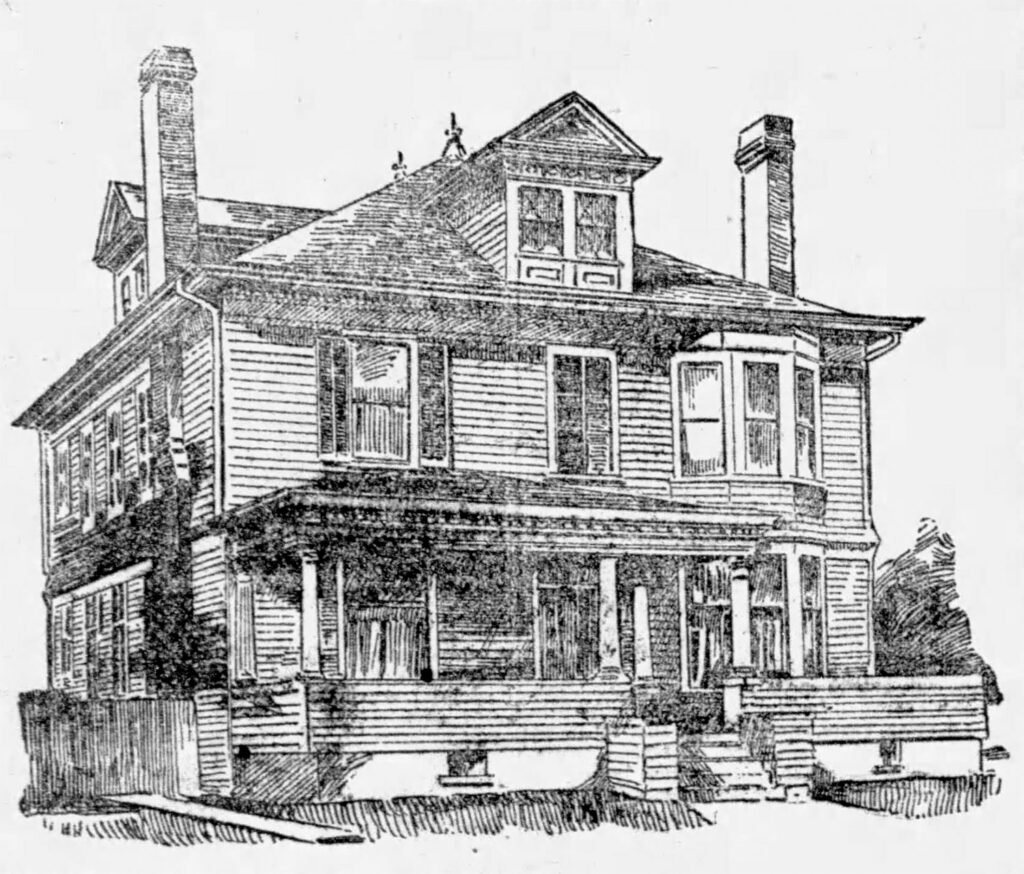

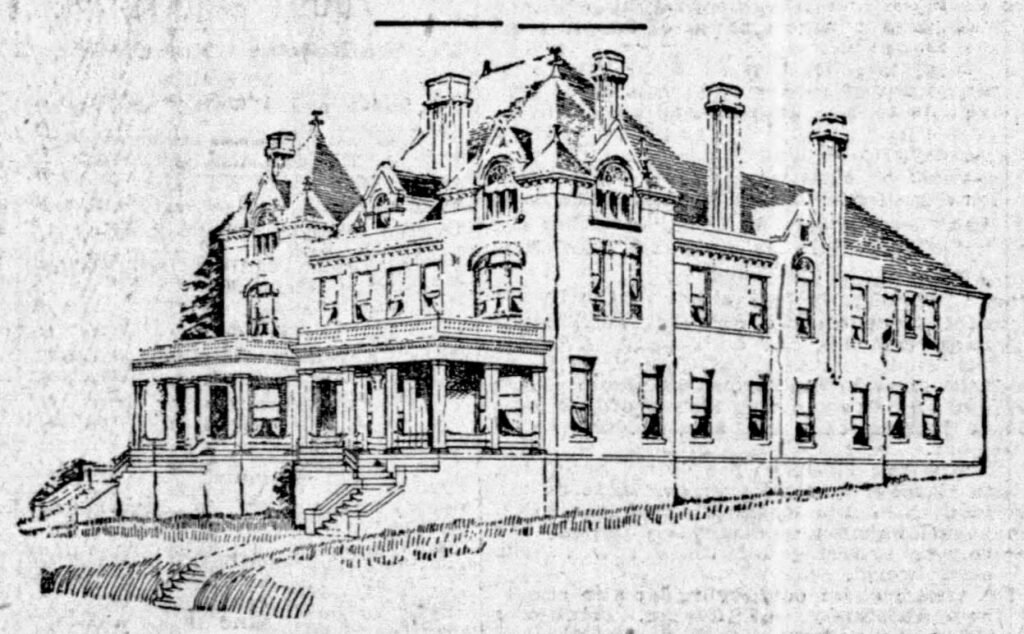

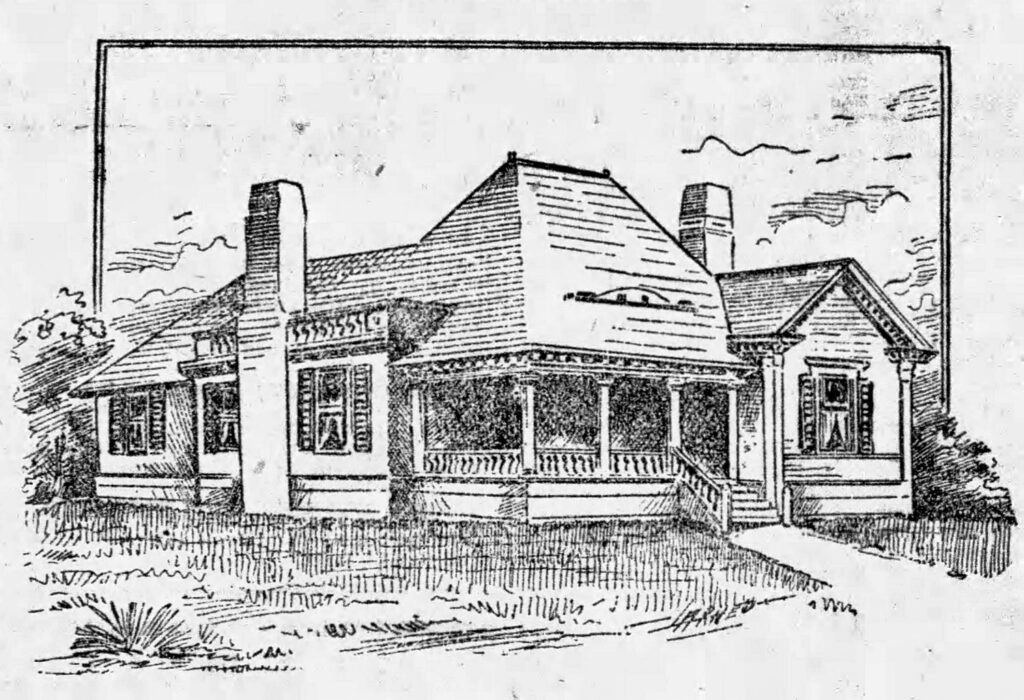

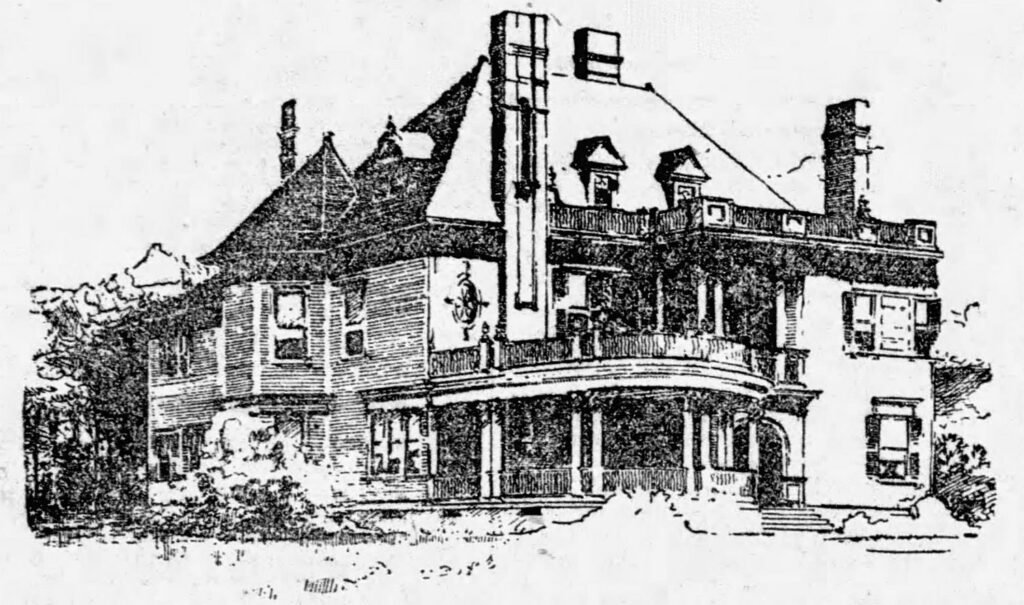

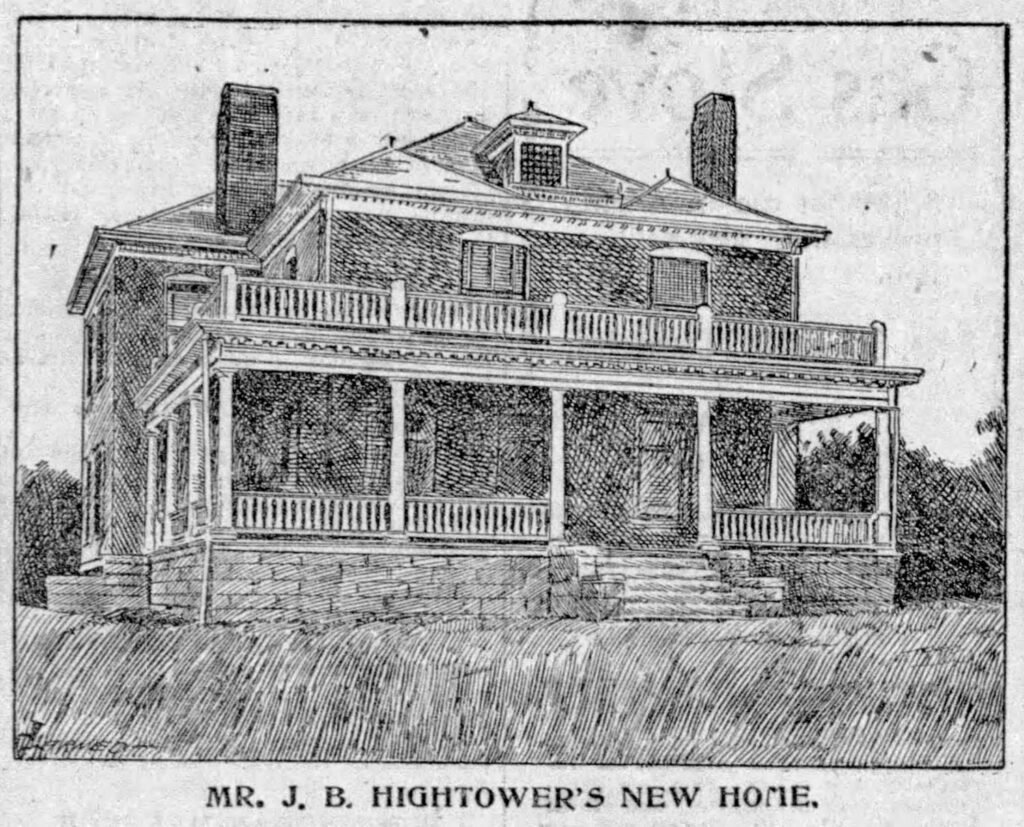

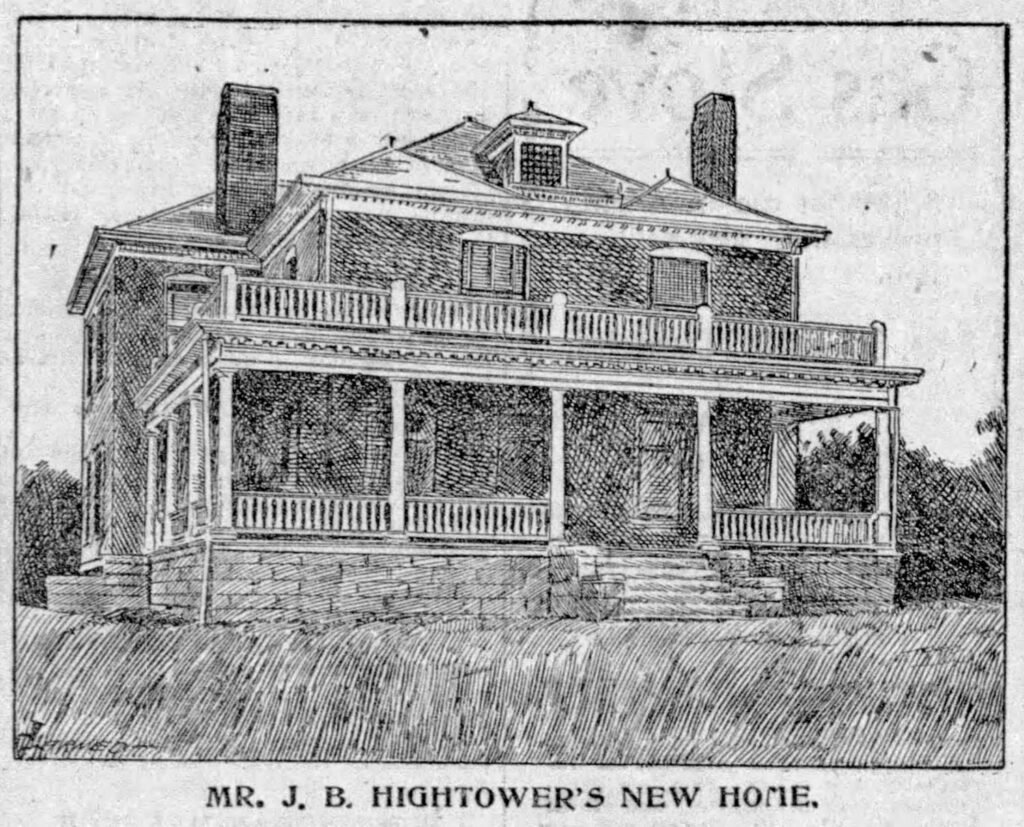

Based on the illustration (pictured above), the home’s exterior was an artless mess: plain, boxy, and brick veneered with crude Colonial ornamentation tacked on, misaligned doors and windows on the front, and a mismatched roof topped by 3 tented peaks and an undersized dormer.

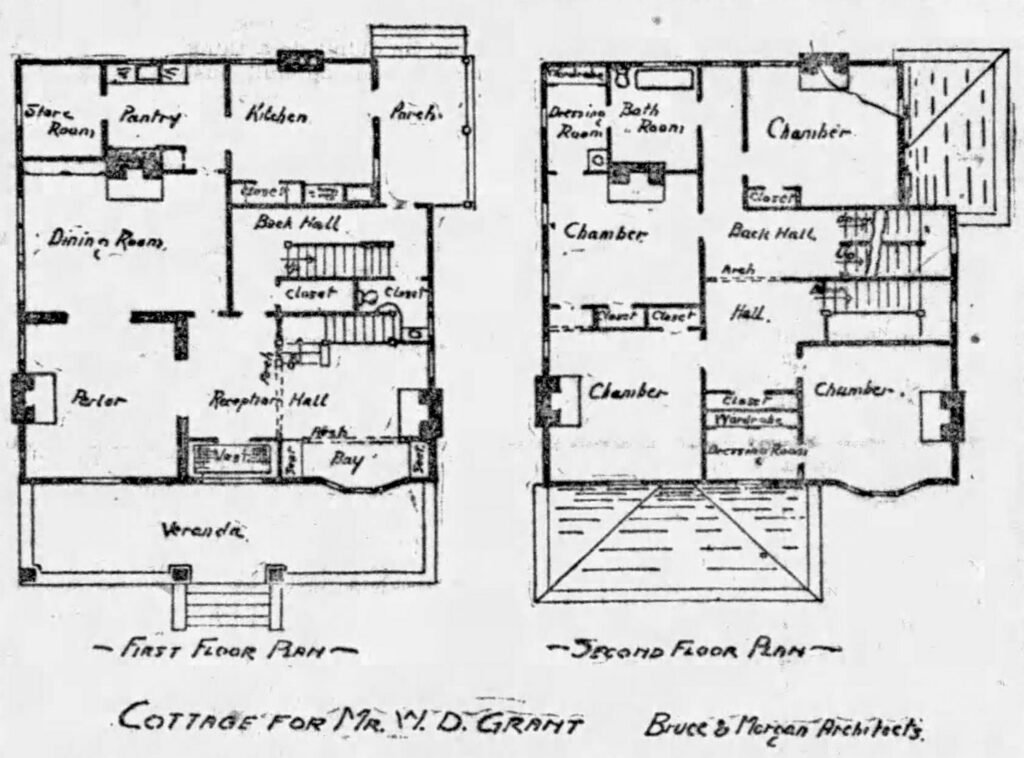

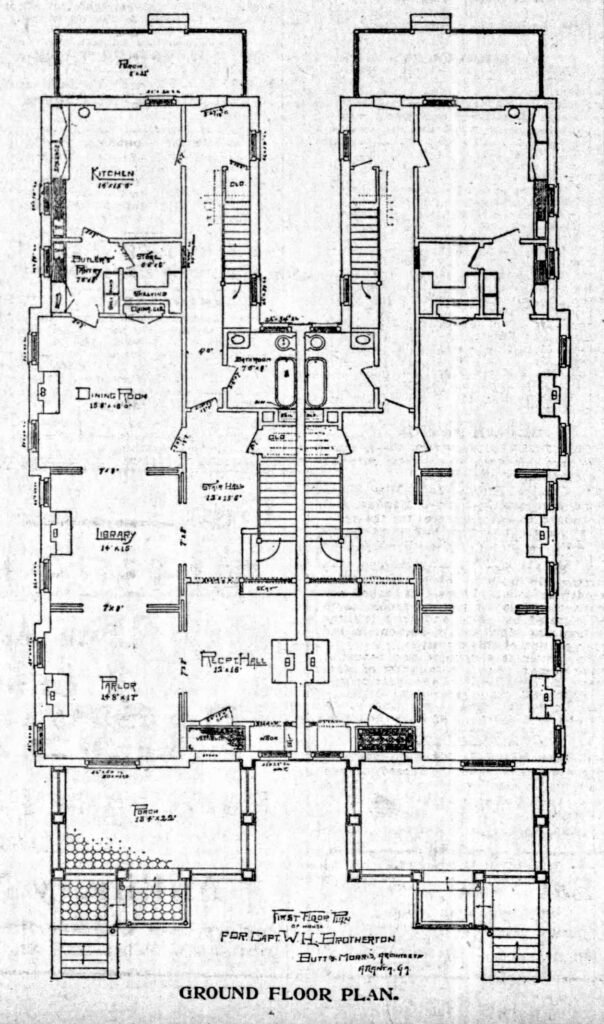

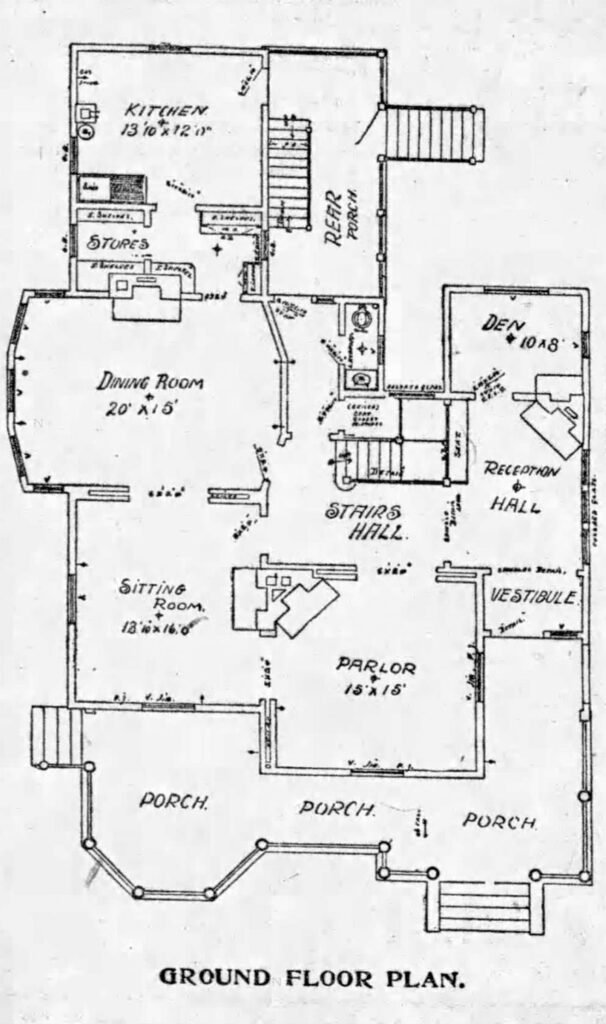

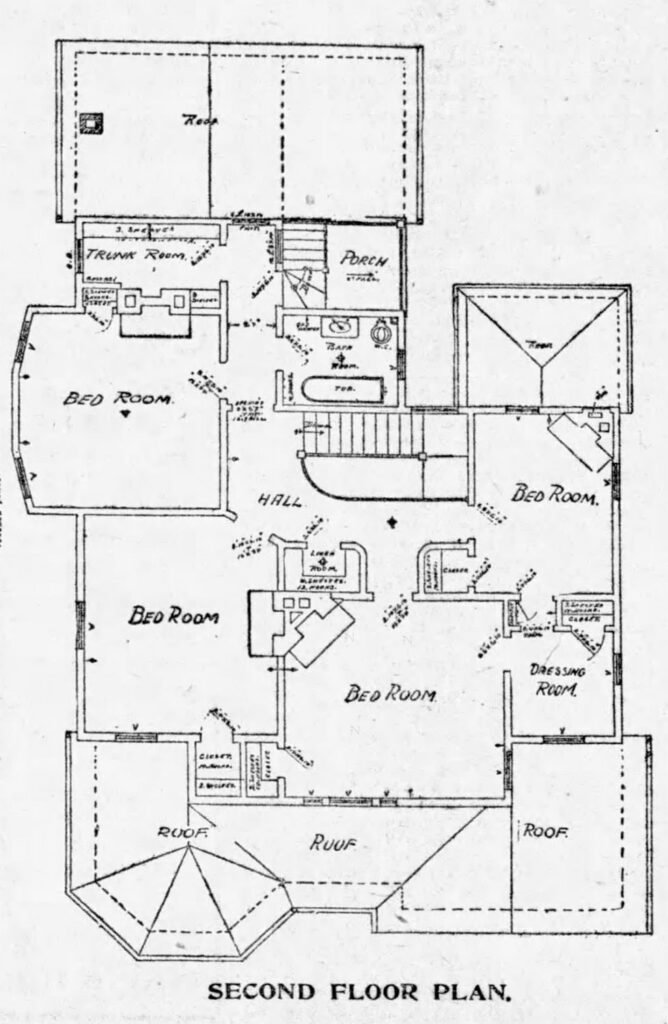

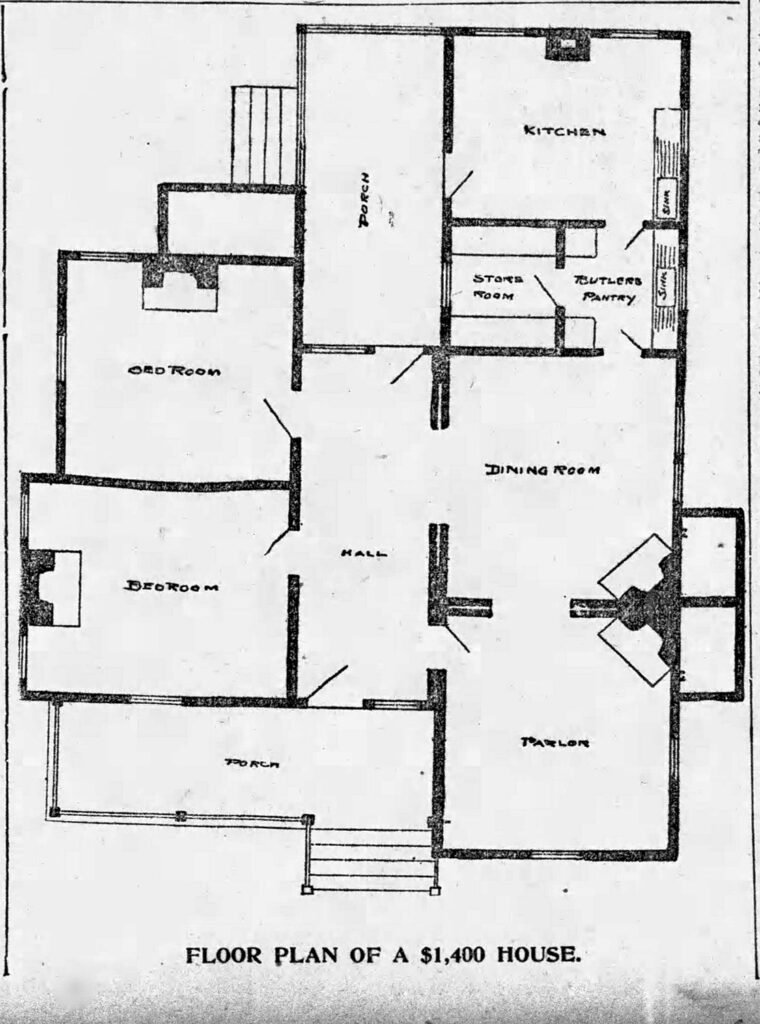

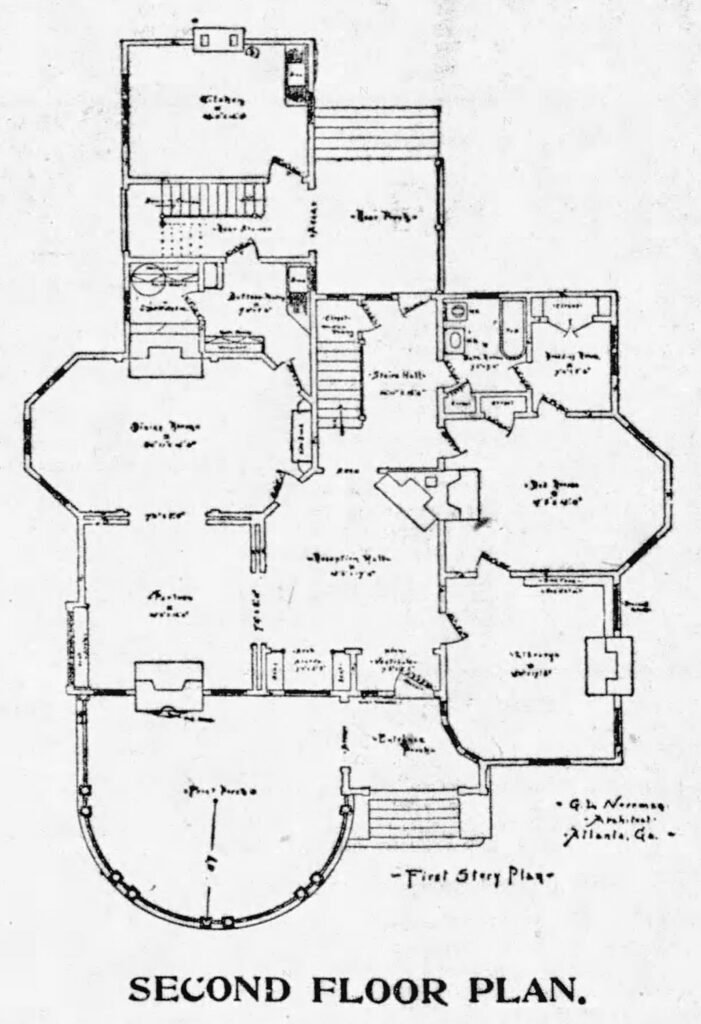

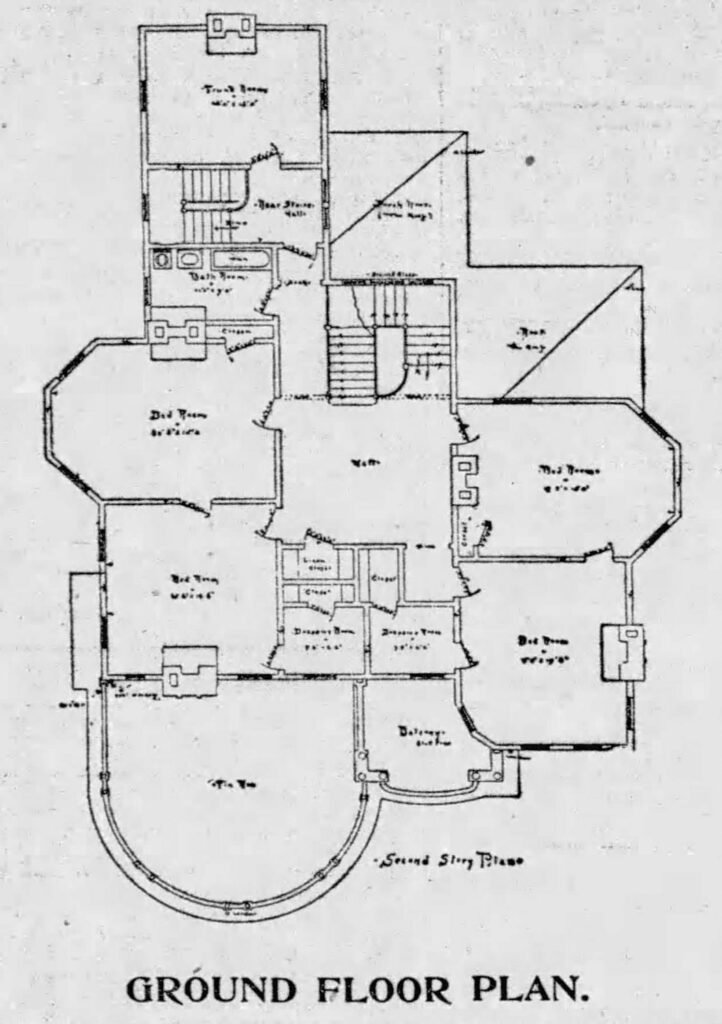

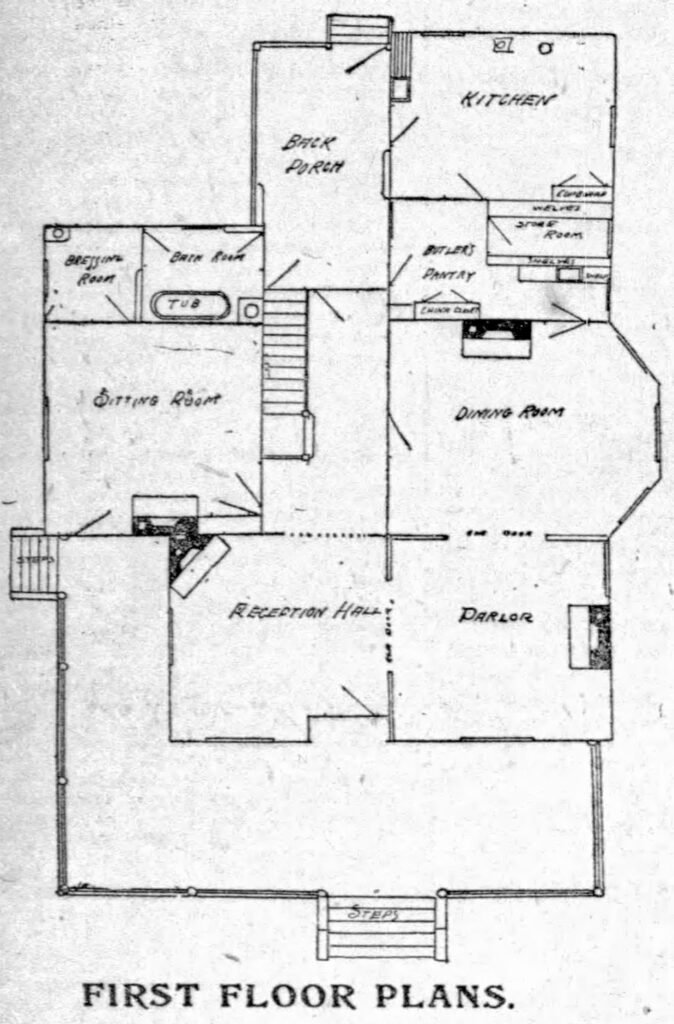

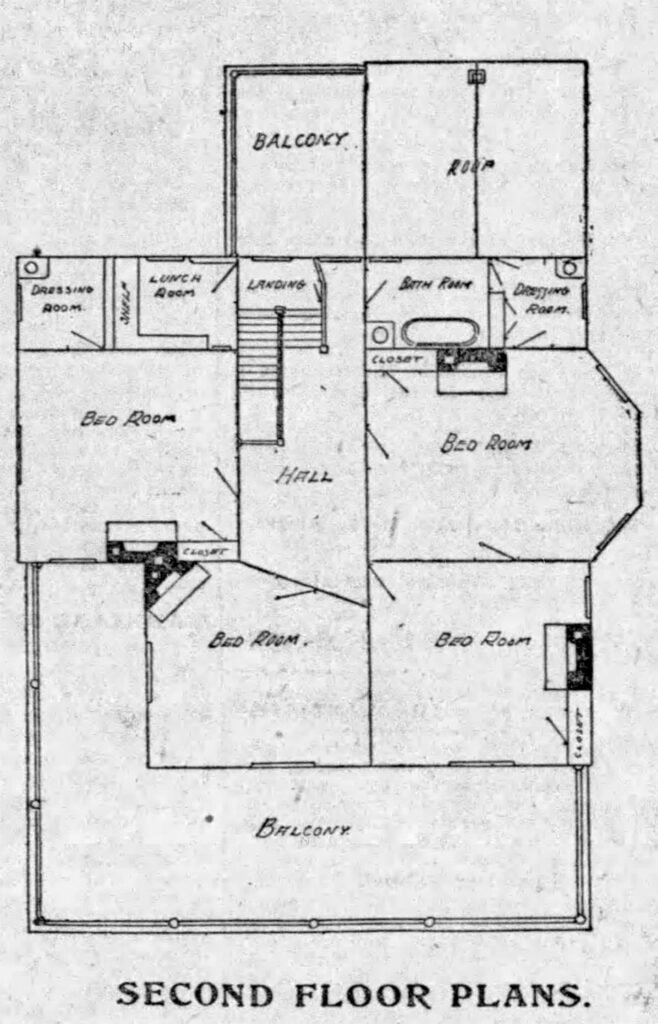

The crudely drawn floor plans (pictured below) are equally baffling and raise multiple questions about the home’s design.

Why, for instance, did the downstairs bathroom have a door to the back porch? Was it really necessary to give the upstairs hall and front left bedroom such awkward shapes to accommodate entry to the front right bedroom? And what the hell was the tiny “lunch room” sandwiched between the 2 floors?

Gibbs was no architect, and it’s likely that he simply swiped a plan from some pattern book and modified it (badly). He was also a notorious asshole.

In November 1909, Gibbs was arrested for assaulting his 17-year-old son in the street, with both of his sons testifying in court that he was “insane”. The trial revealed that Gibbs’s sons objected to his recent marriage to a much younger woman, 10 years after he separated from his first wife.2

Two months later, Gibbs’ young wife sued him for disorderly conduct,3 4 then filed for divorce, citing “his constant threatening, his striking her and his threats to strike her again”.5 6 Among the allegations, the newspapers focused on one in particular: that Gibbs had locked his wife out of their bedroom for placing her cold feet against him, forcing her to sleep in the servant’s room.7 8 9

Mrs. Gibbs said of her husband in a public statement: “He charges me with a great many things, and none of them are true, except that sometimes my feet are cold at night. I do not think this is a crime.”10 She was granted the divorce in April 1910 and awarded $25 per month for alimony.11

In July 1911, Gibbs was sued by his neighbor, Mrs. J. N. Norris, for threatening to “beat her in the face until she couldn’t bat her eyes.”12 Later that year, Gibbs began building an 18-foot-high “spite fence” between their 2 houses, prompting another lawsuit and a court injunction.13 14

During the trial in April 1912, Gibbs — who fired his lawyer and represented himself– was jailed 5 days for contempt of court after declaring all lawyers as “liars, rascals and thieves” and telling the judge: “I don’t give a damn what you do.”15 16

In late 1914, Gibbs was married to his third wife when he bought a pair of shoes from his estranged son’s shoe store, charging them to his son. When his son refused to accept the charge, Gibbs went to the store and angrily confronted him, throwing the shoes at his head.17

In court, Gibbs launched into a tirade on the witness stand, threatening violence against his entire family, and shaking his fist at an attorney, telling him: “I’ll knock you down in a minute if you call me a liar.”18

The spectacle landed Gibbs in jail again,19 20 with a trial held later that month to determine if he was insane.21 The jury determined he was “mentally normal”, based on the testimony of “a number of women” who cited his “honesty in business and personal dealings”.22

Based on the plans here, I can also testify: Gibbs was an honestly terrible excuse for an architect.

In 1901, the house at 55 Hurt Street (later 161 Hurt Street NE) was already occupied by a different owner, Robert K. King,23 24 and by 1927, it was being marketed as (what else?) a boarding house.25 It appears to have been demolished for a 4-story educational building for Inman Park Baptist Church, which completed construction at the address in 1955.26 27

The church sold its property to the state of Georgia in 196728 for the construction of the planned I-485 freeway, with all structures on the east side of Hurt Street demolished for the project. The proposed interstate was officially killed in 1975 after widespread local protest and opposition from the mayor and city council.29 Today, the land is part of Freedom Park.

Journal Model Houses; Mr. J.B. Hightower’s New Home

Mr. J.B. Hightower has just completed a $4,000 residence in Inman Park, and it is one of the most attractive homes in the city. The house is a good type of a combination wood and brick residence. It is claimed that is construction is better in some ways than walls entirely of brick, though it costs less.

The foundation is of stone in front and brick elsewhere. The veranda is 12 feet wide, with an ample vestibule. The reception hall, parlor and diningroom [sic] are furnished in oak, and the other rooms in oiled pine, excepting the kitchen and pantry, which are grained to represent oak. The principal rooms have plate glass windows and the walls are finished with neat picture mold. The plumbing and electrical connections are first class and adjusted in the most convenient manner.

The premises are provided with a barn, carriage house and servants’ quarters, and everything is completed in good style, with first class workmanship. The work was done by Mr. E.T. Gibbs, contractor and architect.30

References

- ↩︎

- “Father Was Fined For Striking Son”. The Atlanta Journal, November 15, 1909, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Contractor E.T. Gibbs Accused By His Wife”. The Atlanta Journal, January 29, 1910, p. 4 L. ↩︎

- “Says Drink And Novels Made Home Very Unhappy”. The Atlanta Journal, January 31, 1910, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Wife Files Divorce Against E.T. Gibbs”. The Atlanta Journal, February 5, 1910, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Mrs. Gibbs Brings Suit For Divorce”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 6, 1910, p. 6. ↩︎

- “Says Drink And Novels Made Home Very Unhappy”. The Atlanta Journal, January 31, 1910, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Not A Crime To Have Cold Feet, Says Woman”. The Atlanta Journal, February 1, 1910, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Read Novels At Night Until She Got Cold Feet”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 1, 1910, p. 4. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Wife Gets Divorce And Small Alimony”. The Atlanta Journal, April 9, 1910, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Rebuked By Neighbor For Punishing Child”. The Atlanta Constitution, July 16, 1911, p. 3. ↩︎

- ‘”Spite” Fence 18 Feet High Causes Suit For Injunction’. The Atlanta Constitution, December 21, 1911, p. 8. ↩︎

- ‘Seeks To Stop “Spite” Fence’. The Atlanta Constitution, December 22, 1911, p. 13. ↩︎

- “Acting As Attorney, Gibbs Abuses Lawyers”. The Atlanta Journal, April 30, 1912, p. 28. ↩︎

- “Kicks Up Rumpus In Court, Is Sent To Jail”. The Macon Telegraph (Macon, Georgia), May 1, 1912, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Contractor In Court, Hurls Abuse At Family”. The Atlanta Journal, November 5, 1914, p. 1. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Father Sent To Jail At Instance Of Son”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 6, 1914, p. 10. ↩︎

- “Is Contractor Crazy?” The Columbus Ledger (Columbus, Georgia), November 24, 1914, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Man’s Honesty Is Proof Of Mental Soundness”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 24, 1914, p. 4. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1901) ↩︎

- “C.S. King Dies Suddenly Today Of Heart Failure”. The Atlanta Journal, June 17, 1902, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Rentals”. The Atlanta Journal, August 24, 1927, p. 29. ↩︎

- “Inman Park Pastor Ending Third Year”. The Atlanta Journal, April 9, 1955, p. 4. ↩︎

- Barre, Laura. “Inman Park Baptists To Dedicate Building”. The Atlanta Journal, December 10, 1955, p. 10. ↩︎

- “Inman Park Baptists Will Hold Homecoming”. The Atlanta Journal, August 12, 1967, p. 6. ↩︎

- Nordan, David. “FHA Sounds Death Knell For Ballhooed I-485”. The Atlanta Journal, April 22, 1975, p. 6-A. ↩︎

- “Journal Model Houses; Mr. J.B. Hightower’s New Home”. The Atlanta Journal, June 11, 1898, p. 8. ↩︎