The Background

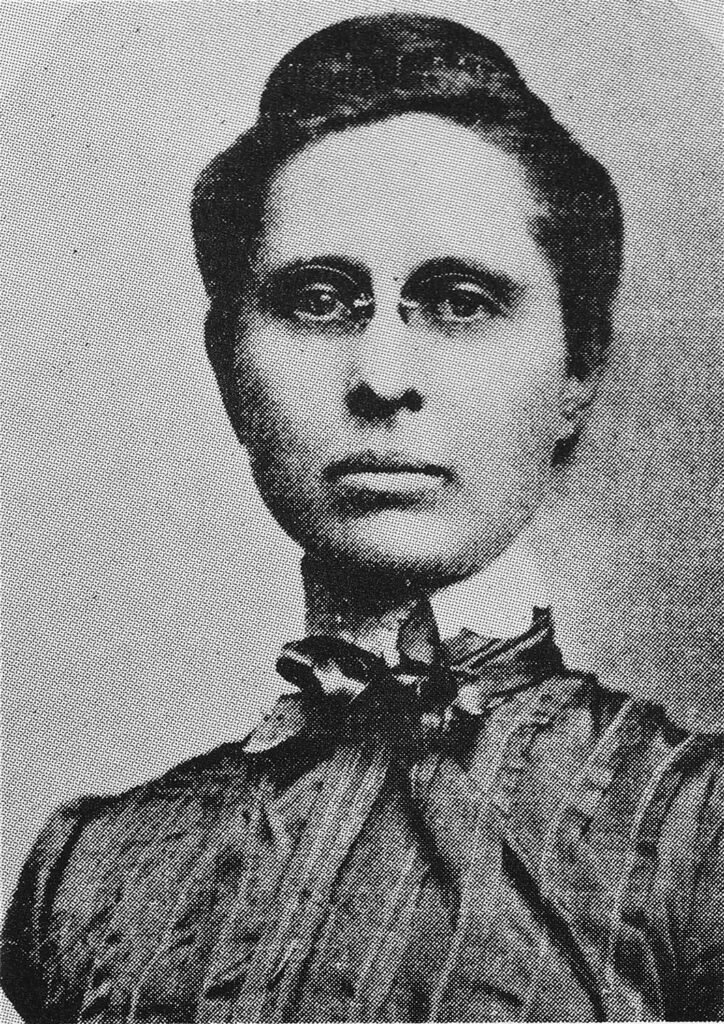

The following article appeared in The Atlanta Georgian and News in 1910, and includes a profile of Henrietta C. Dozier, the first female architect in Atlanta and the Southeastern United States.

While Dozier is the primary subject of the article, another “woman architect” of Atlanta is mentioned, Leila Ross Wilburn, as well as a feisty, anonymous attorney who apparently designed homes as a hobby.

Wilburn was a self-taught designer and unlicensed architect who started her own practice 8 years after Dozier, although she is sometimes erroneously credited as the South’s first female architect.

Her designs were unremarkable, but Wilburn found success by following the lead of architects like George F. Barber, publishing a series of pattern books for those looking to build their own homes inexpensively.

While Dozier is largely forgotten in Atlanta, Wilburn’s work is still widely touted by locals, particularly in nearby Decatur, Georgia, where many homes by her design remain. You will find no such celebration of Wilburn here.

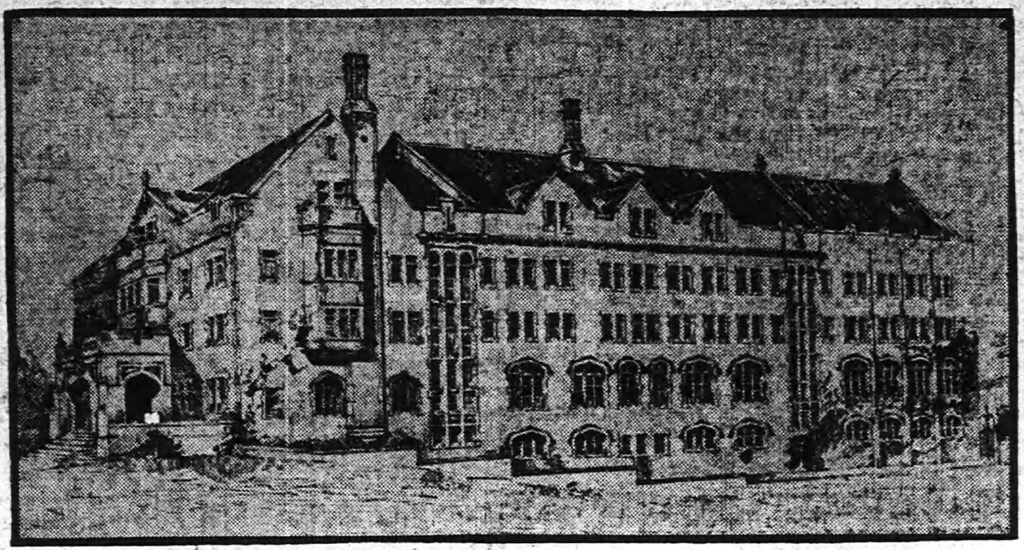

As Dozier notes in this article, the Diocese of Georgia, headed by Bishop C.K. Nelson, commissioned her to design a project called Nelson Hall (pictured above), a 3-story school for girls on Peachtree Street in Atlanta.2 3 4 5 6

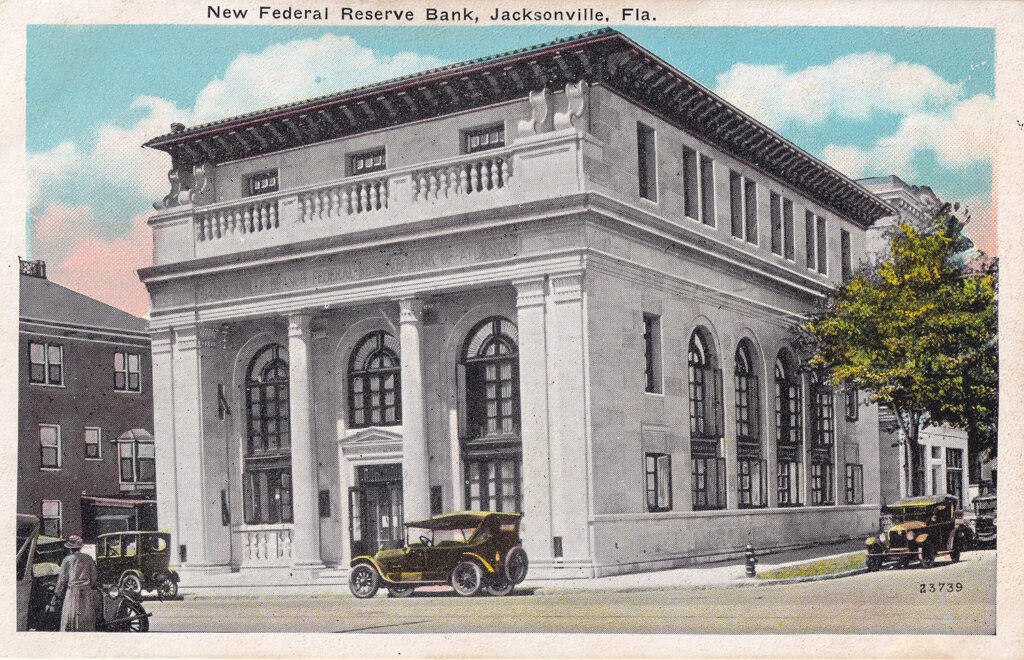

Dozier was a devout Episcopalian, and the diocese was her most faithful client in Atlanta:7 among other projects for the organization, she designed the first chapel for Atlanta’s All Saints Episcopal Church,8 9 a 2-story building known as the Southern Ruralist building (1912, demolished),10 11 12 13 14 and St. Michael’s Episcopal Church in Fitzgerald, Georgia, which still survives.

Had Nelson Hall been completed, it would have been one of the major works of Dozier’s career, but the project failed to materialize.

The Woman Invasion? Here Are Two Women Architects in Atlanta, and They Plan Sure-Enough Houses, Too

Miss Henrietta C. Dozier Talks of Her Work–She Designs Factories and Churches and Any Sort of Building.

By Dudley Glass.

“Why, anything from a chicken coop to a church. But my favorite line? The big things with lots of money in them, of course.”

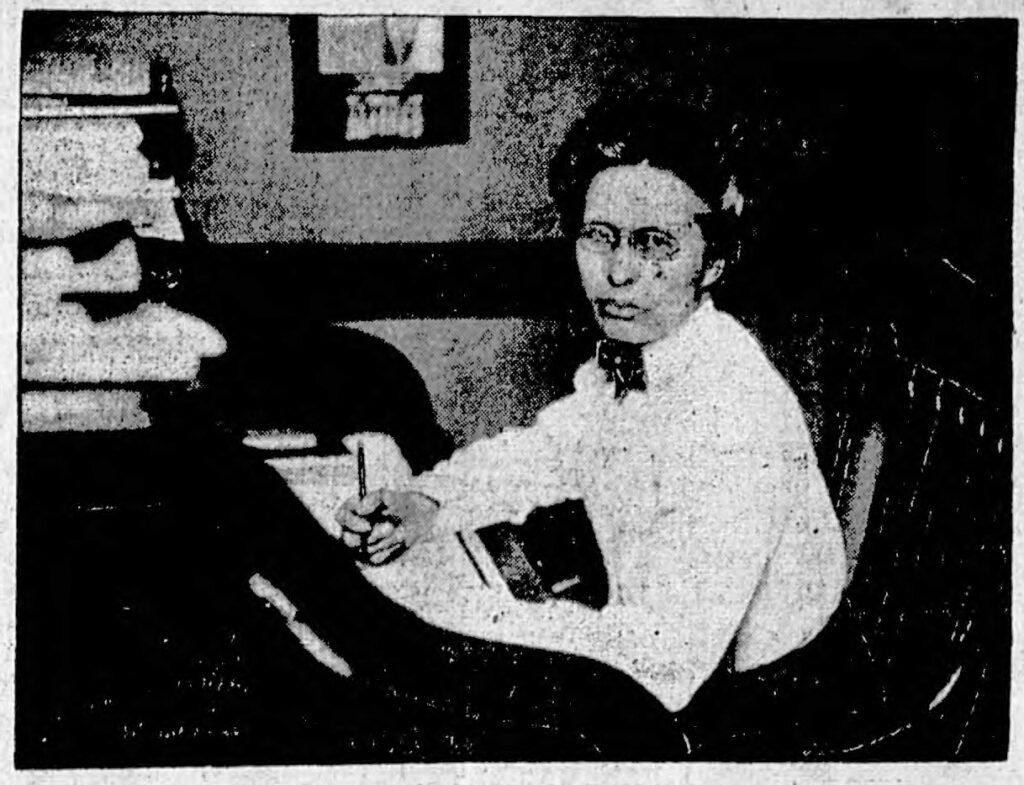

Miss Henrietta C. Dozier leaned back in her office chair and smiled in a friendly way. She seemed to think it odd that any one should be surprised at a woman’s success in architecture. But, then, women are giving their brothers a race in every line nowadays, except steeple climbing, and it wouldn’t surprise me to see one start that. Why, there’s even a woman—but that’s good enough for a story of its own, so I’ll save it.

“Why not?” asks Miss Dozier. “There’s very little difference between men and women. There’s a lot more difference between individuals. I studied architecture in college, served a long apprenticeship for practical experience and had my ups and downs in the school of practical work. Why shouldn’t I be a good architect? I don’t ask any favors because I am a woman. Can I give satisfaction? That’s the main point.“

No Fashion Plates There.

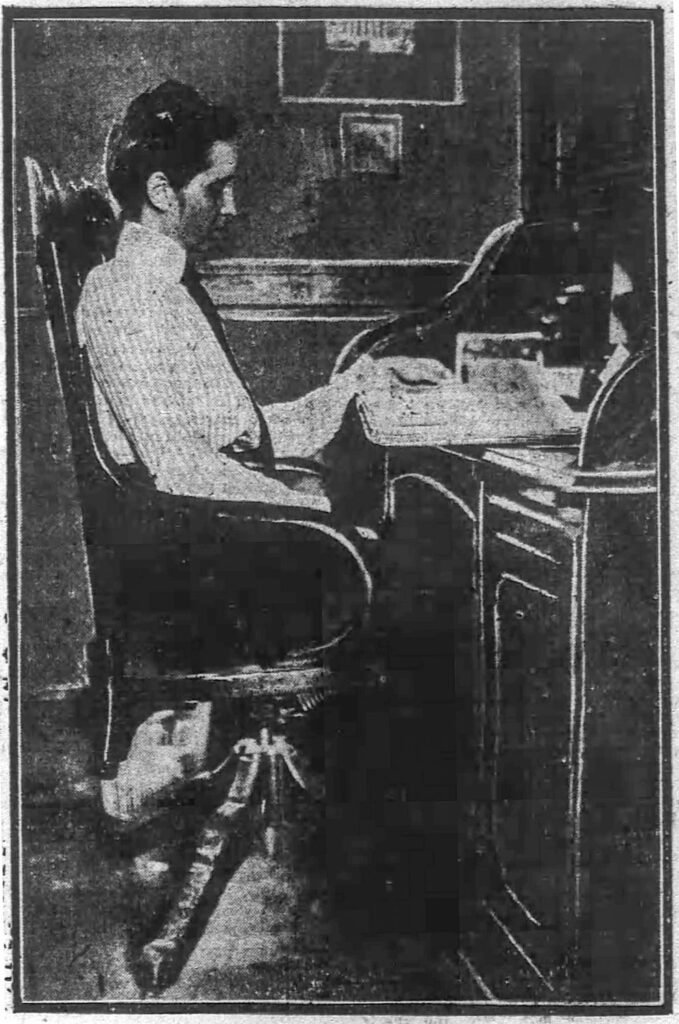

Certainly she seemed to have sunk the woman in the architect during business hours at least. Her desk, a big roll-top with a hundred pigeon-holes, was well covered with papers and plans. I took a peep at a stack of magazines on the corner and instead of fashion plates and The Ladies’ Home Journal, I found only The Architectural Record and The Engineering Review. There were no Christy sketches on the wall of her office in the Peters building, but a dozen front elevations of handsome buildings, a glimpse or two of the Parthenon and the Coliseum and, in the place of honor over the desk, a big plate of the Boston Atheneum.

No, she isn’t an imported product. Boston furnished some of the science, but Miss Dozier is of the South Southern. You couldn’t chat with her for five minutes without learning that. But she would rather talk of her work than her personality, anyway.

She’s Building Nelson Hall.

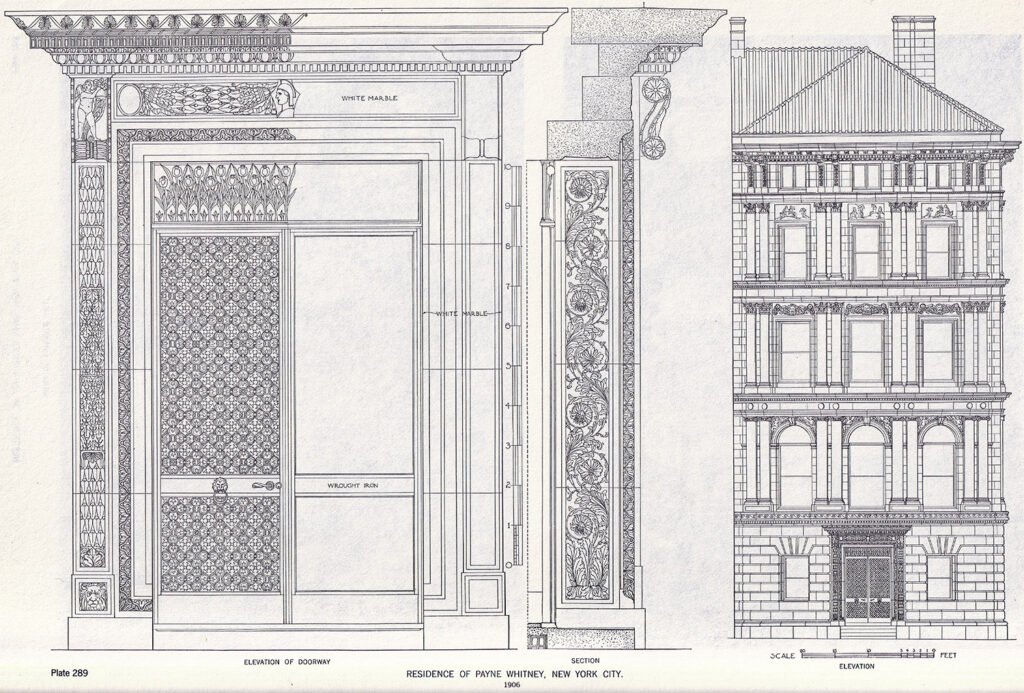

“The biggest thing I ever tackled?” repeated the woman architect after a question. “Why, that, I suppose,” pointing at a drawing on the wall. “That” was an elevation of Nelson Hall, the splendid Episcopal school for girls which is soon to be erected on Peachtree-st. by Bishop C.K. Nelson and his diocesan workers.

“That’s been keeping me pretty busy lately,” she continued. “Nice of them to give me such a fine piece of work, isn’t it. Yes, it’s Tudor architecture. It’s going to be very handsome.”

“But I’ve built all sorts of things. There were some little houses at first—you know a beginner takes what she can get—but that was a long time ago. I’ll take a contract for any character of structure, factory, church—I’ve built several churches—homes, but I like the big things best, of course.”

“Do you really get out in the weather and climb over the half-finished buildings and boss contractors and all that sort of thing?” I was wondering if this neatly groomed woman had her troubles with workmen like ordinary folk or if she did all her directing from a steam-heated office.

A Woman as a “Boss”.

“Of course,” she replied. “No, I don’t ‘boss’ anybody much. That isn’t necessary. Every contractor I have known–with one exception–has been nice to me. All I need do is show them what I want.”

Miss Dozier smiled as she recalled the exception. A contractor had used some inferior laths against her express direction. There had been a letter or two, a telephone message, an ultimatum from the architect—and those laths came off again and new ones went in their place. The recollection seemed to amuse her.

“Sometimes they think a woman doesn’t know,” resumed the architect. “I drew plans for a big factory not long ago and had the weights all supported by—” (here she gave a brief but graphic description of her plans.) “The owners insisted that the idea wouldn’t do. No mill had ever been built that way, therefore it wasn’t the right way. And now, right in that late magazine, I find a big factory of the same kind using exactly the same idea I proposed. I’m glad to be vindicated—tho I knew I was right all the time.

“Women clients? No, they are no more trouble than the men. No, I can’t say that women are any more disposed to give another woman work than are the men. You remember I told you men and women were mightily alike. I’ve done lots of work for both.“

And then Miss Dozier begged me to excuse her a moment while she stopped for an animated discussion with a contractor whom she had summoned by phone. The cataract of technical terms that overflowed from the inner office while they bent over plans and blueprints gave me a feeling that I’d been trying to talk a strange language, and I slipped away.

She’s Not the Only One.

But Miss Dozier isn’t the only woman architect in Atlanta, even tho she is perhaps the best known, a natural consequence of her seven years’ service here and her degree from the American Institute of Architects. Just below her in the same building on the third floor, is the office of Miss Leila Ross Wilburn, a young woman who was too busy with pencil and compass when I entered to give much more than a pleasant smile and a promise of a talk some other time. Miss Wilburn, who lives in Decatur, has graduated from drafting for other architects into a nice business of her own, and has pluck and energy enough to accomplish wonders. She did the Goldsmith apartments on Peachtree and Eleventh-sts., the fine gymnasium at the Georgia Military academy and the academy’s Y.M.C.A. chapel and recreation halls, and has successfully completed a number of Atlanta buildings.

And there’s still another–a woman who draws plans and builds houses for herself. I met her in Inman Park, where she was making a hard-headed carpenter hang a door according to her ideas instead of his own.

“Are you an architect?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “I’m a lawyer, and if you write me up in the paper I’ll sue you.”

She wasn’t deceiving me. She really is a full-fledged lawyer, and builds houses merely because she likes the work and the results. But remembering her threat, I’m not going to write her up, not even give you her name.16

References

- “Nelson Hall, The New Episcopal School”. The Atlanta Constitution, March 19, 1910, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Bishop Nelson Will Head School For Young Women”. The Atlanta Journal, July 13, 1909, p. 3. ↩︎

- ‘”Nelson Hall” Charter Granted By Court’. The Atlanta Constitution, July 14, 1909, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Will Open New College For Girls September, 1910”. The Atlanta Georgian and News, July 14, 1909, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Nelson Hall, The New Episcopal School”. The Atlanta Constitution, March 19, 1910, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Miss Stewart Here To Represent Nelson Hall”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 5, 1911, p. 5. ↩︎

- Spotlight: Henrietta Dozier – Jacksonville History Center ↩︎

- “History of All Saints’ Parish and Church Just Complete”. The Atlanta Constitution, April 8, 1906, p. 2. ↩︎

- “All Saints’ Episcopal Church Will Be Formally Opened This Morning With Beautiful And Impressive Service”. The Atlanta Journal, April 8, 1906, p. S1. ↩︎

- “Church Asks Permit To Erect $23,00 Building.” The Atlanta Georgian, July 3, 1912, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Episcopalians May Erect Big Building”. The Atlanta Journal, July 3, 1912, p. 2. ↩︎

- “The Real Estate Field”. The Atlanta Journal, July 8, 1912, p. 19. ↩︎

- “The Real Estate Field”. The Atlanta Journal, August 1, 1012, p. 19. ↩︎

- “Wanted–Female Help.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 15, 1912, p. 5. ↩︎

- Glass, Dudley. “The Woman Invasion? Here Are Two Women Architects In Atlanta, And They Plan Sure-Enough Houses, Too.” The Atlanta Georgian and News, February 19, 1910, p. 1. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎