Don’t let Atlanta historians fool you: A. Ten Eyck Brown (1878-1940) likely had little to do with the design of this monumental structure, which ranks among the most exquisite buildings in the city.

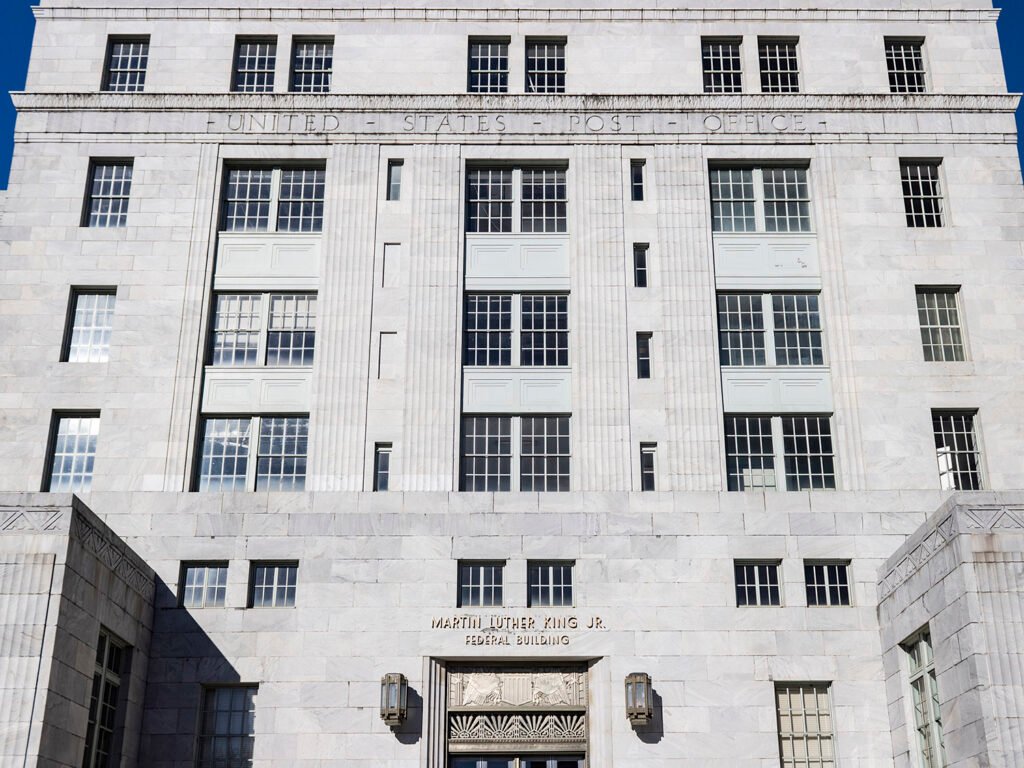

Opened in December 19331 as the United States Post Office, it appears the project was primarily designed by Brown’s associate architects, Alfredo Barili, Jr., and J. Wharton Humphreys, who established their own firm a few years later.2

Compare the later works credited to Brown with those of his early years, and it’s clear that his own skills were inadequate for the more sophisticated designs that emerged from his firm in the 1920s onwards — this project is no exception.

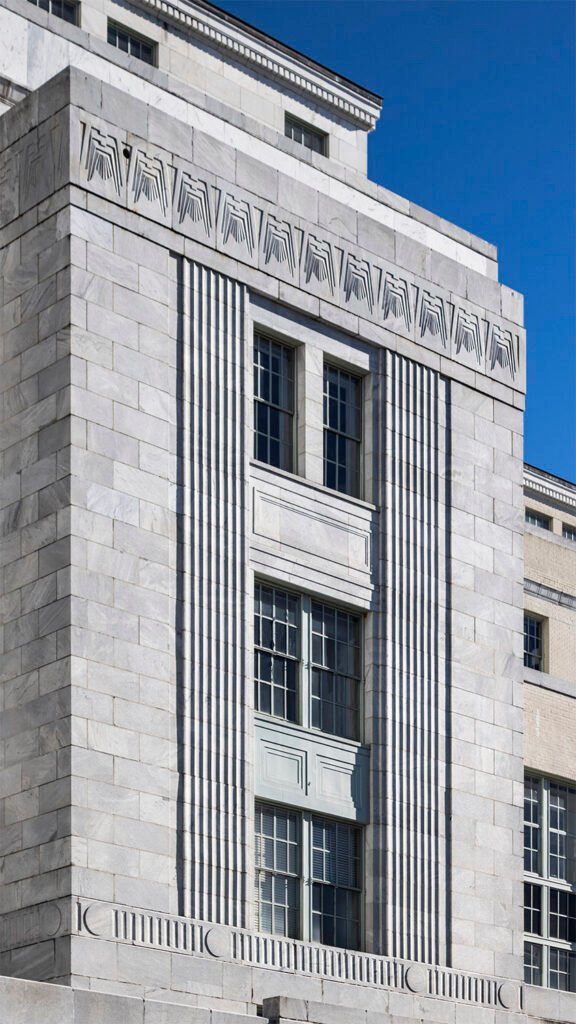

Designed in the Classical Moderne style, the building sits atop a base of Stone Mountain granite and is sleekly clad in Georgia marble.3

The structure’s otherwise smooth facades on the east and west are punctuated by a trio of slightly recessed bays that recall Brown’s earlier design for the Fulton County Courthouse, but the effect is much more successful here.

Indeed, the courthouse design is a joyless mess: the building’s facade is cluttered with windows of varying sizes, and the deeply-recessed center bay, supported by six multi-story columns, resembles a giant jail grating.

In this design, the variation of the bays is much more subtle, and the windows are given space to breathe, providing enough contrast and visual balance for a pleasing and cohesive composition.

This building also shines in its incorporation of fine textural detail, trimmed with pilasters, friezes, and stringcourses in stark geometric patterns, many of pre-Columbian inspiration. Emphasizing the structure’s bold ziggurat form, the design evokes the image of some ancient American temple dropped into a modern metropolis.

The project was completed for the princely sum of $3 million,4 and the volume of materials used in its construction is staggering: the structure is composed of 12,222 pieces of marble totalling 4,798,404 pounds, with the largest block weighing 8,400 pounds.5

Atlanta, of course, never pays for quality architecture, and this bulwark of a building exists only because it was bankrolled by the United States government.

At the time, federal building projects were supervised by the U.S. Treasury, and Brown was a natural choice to pick as the lead architect, since he began his career in the office of the supervising architect of the Treasury.6 7

Brown was approaching the end of his life and career in the 1930s and was well-respected in Atlanta and the Southeast. Known as “Tony” to his friends,8 he became one of the city’s wealthiest architects in the early 20th century, with his firm designing dozens of large-scale public buildings across multiple states, although it appears his fortunes were greatly reduced during the Depression.

Preston Stevens of Stevens & Wilkinson described him as “debonair and attractive,” and recalled a claim by another architect, Francis P. Smith, who said that ‘”Tony” could almost hypnotize his clients by sitting across the table from them and sketching designs upside down.’9

I can’t criticize Brown too much for claiming primary credit on this project, as most architects of the era did the same. The myth of the lone designer had long become untenable, and by the turn of the 20th century, every Atlanta architect managed a team of design assistants.

As building projects grew increasingly larger, costlier, and more complex to manage, most prominent architects effectively became figureheads, promoting their businesses and securing commissions while delegating actual design work to their employees.

It’s well documented that numerous projects credited to Atlanta architects of the time, like W.T. Downing, Morgan & Dillon, W.A. Edwards, and Hentz, Reid & Adler — to name a few — were designed by assistants, many of whom went on to establish their own firms.

Brown at least had the decency to share credit with the actual designers of his projects — often listing them as associate architects or supervising architects — a practice he began in 1922, when he was appointed the supervising architect for more than twenty public school buildings in Atlanta,10 11 nearly all of which were designed by other architects.12 13

Contrast his approach with, say, G. Lloyd Preacher, who claimed credit for every work produced by his firm, although it’s abundantly obvious which projects weren’t his own. The most striking example is Atlanta’s fine neo-Gothic city hall, credited to Preacher but designed by one of his employees, George H. Bond,14 who was an infinitely more talented designer.

Questions of credit aside, the former United States Post Office (later renamed the Martin Luther King, Jr. Federal Building) is one of the few structures in the city with any actual design caliber, and its quality of craftsmanship and attention to detail are unknown to modern architecture, in Atlanta or elsewhere.

References

- Hamilton, Tom J., Jr. “Leaders Laud Administration Policies at Dedication of Atlanta’s New $3,000,000 Post Office Building”. The Atlanta Journal, December 3, 1933, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Barili & Humphries Architectural Firm Is Announced Here”. The Atlanta Journal, February 21, 1937, p. 6-D. ↩︎

- “New Post Office Is Dedicated And Accepted By City”. The Atlanta Journal, February 19, 1933, p. 1-B. ↩︎

- Hamilton, Tom J., Jr. “Leaders Laud Administration Policies at Dedication of Atlanta’s New $3,000,000 Post Office Building”. The Atlanta Journal, December 3, 1933, p. 1. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “New P.O. Building Praised”. The Atlanta Constitution, March 27, 1931, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Noted Architect Succumbs Here At Age of 62”. The Atlanta Constitution, June 9, 1940, p. 1. ↩︎

- Stevens, Preston. Building a Firm: The Story of Stevens & Wilkinson Architects, Engineers, Planners Inc. Atlanta (1979), p. 67. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “A. Ten Eyck Brown Made Supervising School Architect”. The Atlanta Constitution, January 21, 1922, p. 1. ↩︎

- “May Start Building Of 30 New Schools In Near Future”. The Atlanta Journal, January 22, 1922, p. 1. ↩︎

- “School Building Program Adopted By Board Friday”. The Atlanta Constitution, March 25, 1922, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Architect To Split School Plan Work”. The Atlanta Journal, March 25, 1922, p. 9. ↩︎

- Stevens, Preston. Building a Firm: The Story of Stevens & Wilkinson Architects, Engineers, Planners Inc. Atlanta (1979), p. 70. ↩︎