The Background

This is the third in a series of articles published by The Atlanta Journal in 1898 featuring illustrations and floor plans of residences designed by Atlanta architects.

The article was published in January 1898 and presented the Susie Wells Residence, designed by Butt & Morris, an architectural duo consisting of James W. Butt and Marshall F. Morris. Butt established his practice in Atlanta in 1893,1 and Morris apparently joined in 1896.2

Scant information is available about either Butt or Morris, and little of the firm’s work survives in Atlanta. While they appeared to enjoy some success in the late 1890s and early 1900s, their last newspaper mention was in 1905,3 and the partnership seems to have disbanded around 1909.4 5

There’s also nothing to indicate that Butt & Morris were good designers: city building permits reveal that most of their work consisted of modest, inexpensive homes and buildings, and illustrations and plans of their designs suggest a distinct lack of talent.

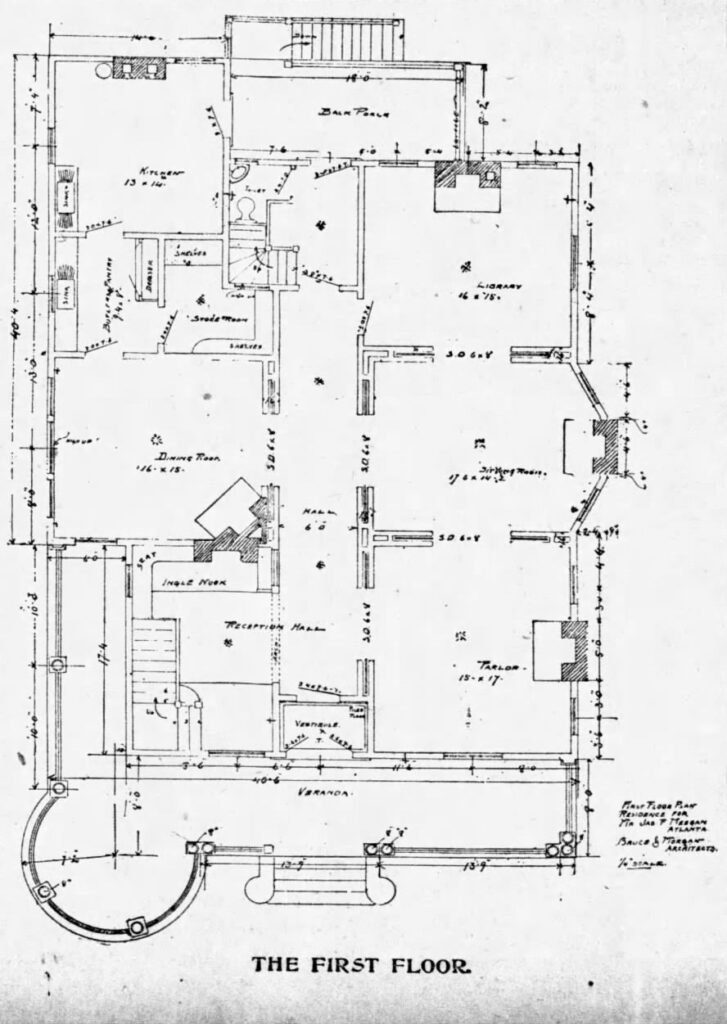

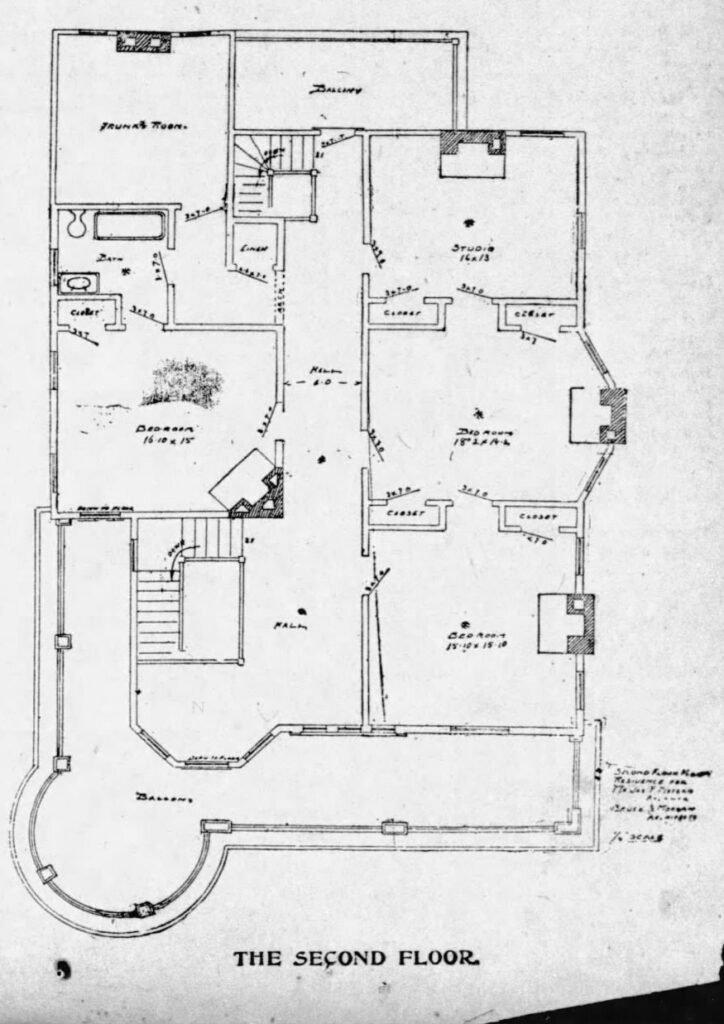

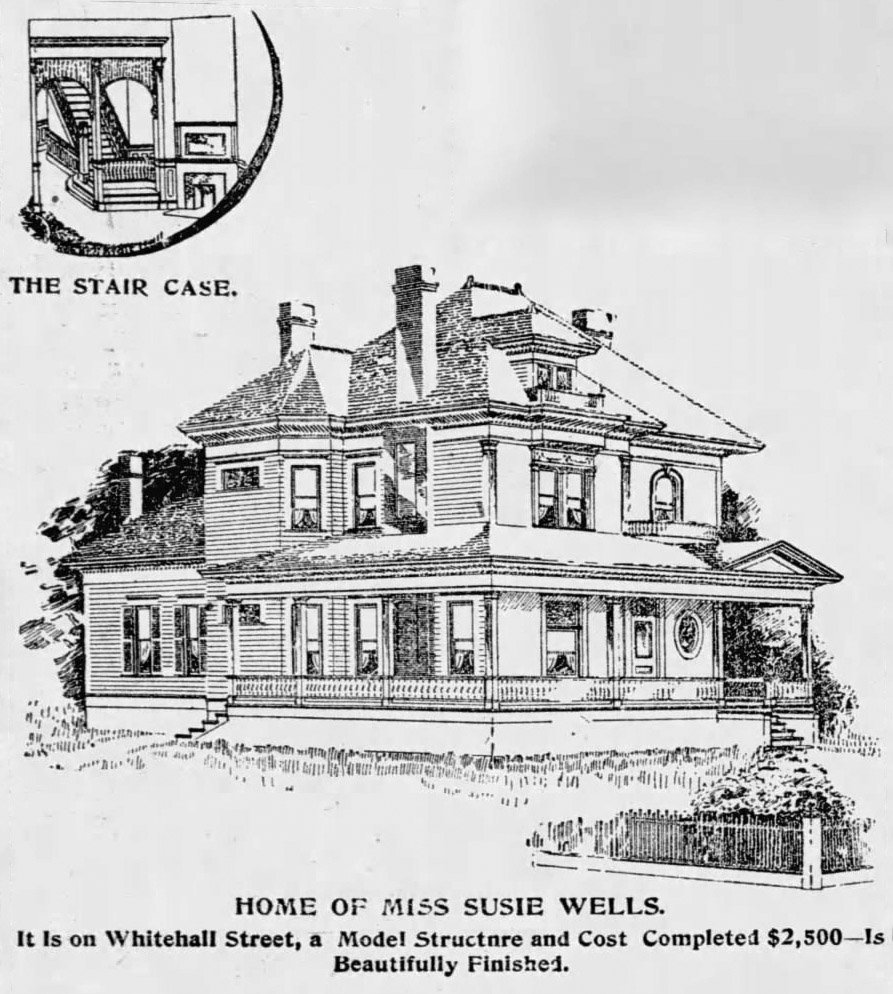

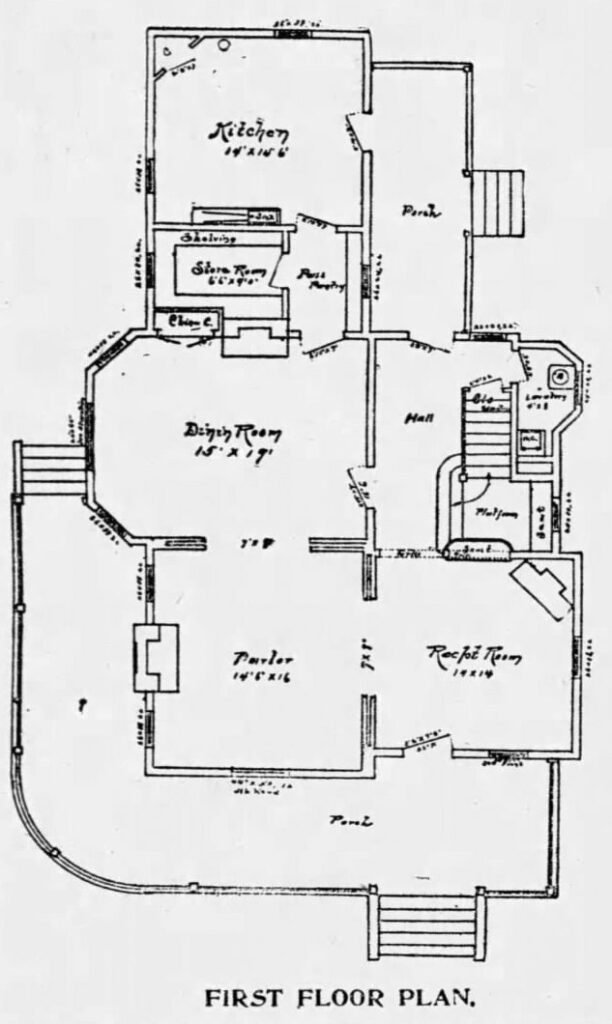

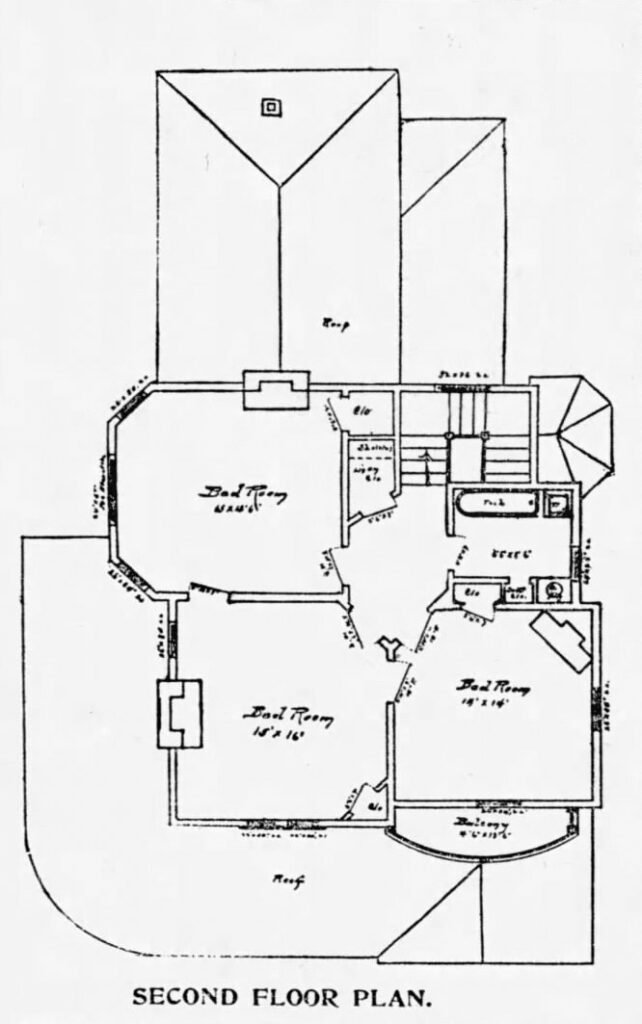

Consider the plans here, which include an awkwardly shaped lavatory tacked on to the first floor, a baffling hall design on the second floor, and oddly-shaped closets shoved into the corners of the bedrooms, among other poor choices.

Located at the southwest corner of Whitehall and McDaniel Street in what is now Atlanta’s Mechanicsville neighborhood, the Wells home didn’t survive 15 years. Wells rented out the house following the death of her mother in January 19066 7 and then sold it in early 1913,8 when it was replaced by a one-story brick auto garage.9 10

Journal Model Homes; Residence of Miss Susie Wells

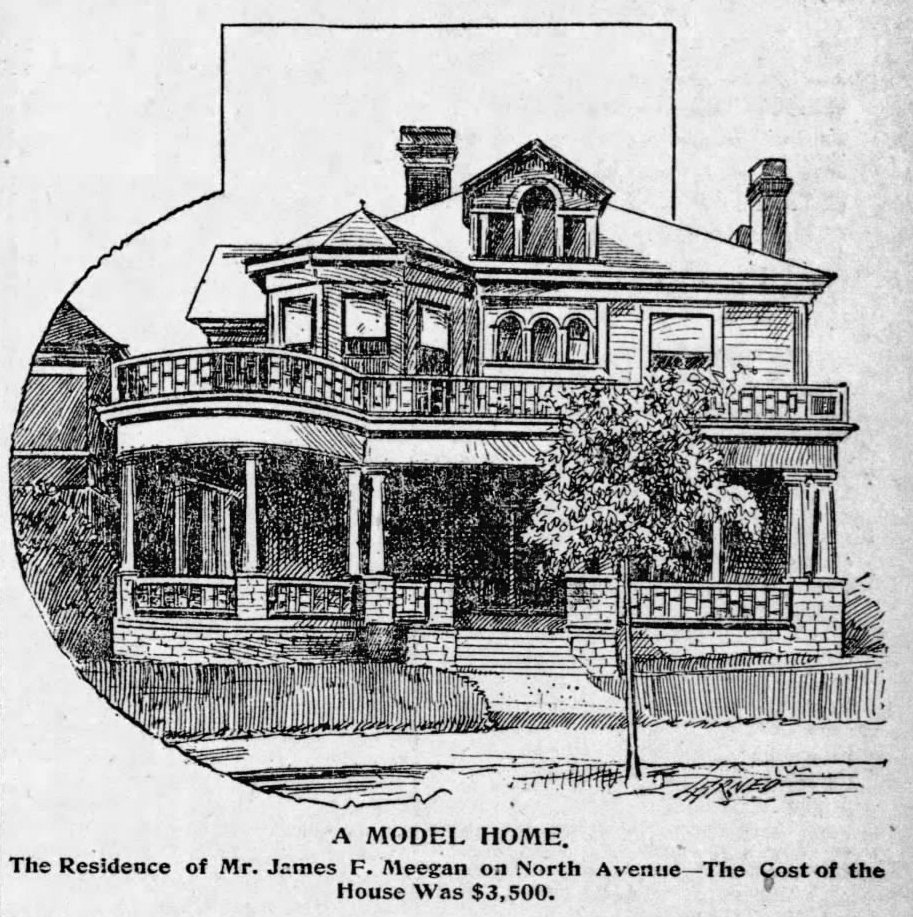

The accompanying cuts represent one of the handsomest seven-room houses in the city. It was built for Miss Susie Walters at 446 Whitehall Street last summer, and was completed in the early fall at an actual cost of $2,500. It is in design and finish one of the most attractive houses ever built in Atlanta at this price, and the arrangement is exceedingly convenient.

The foundation is a solid brick wall, and the chimneys are of ample size and well built. The timber is select pine and sized to make even walls. The roof is of shingles, painted black, and has the appearance of a slate roof. The floors are double and storm-sheeting underlies the weather-boarding. The interior finish is select pine of natural color in hard oil.

The arrangement of the reception hall, parlor and dining room is exceedingly convenient and attractive, and a very pretty grill work separates the reception hall from the stair hall, as will be seen in the illustration. The doors are select pine veneered, showing no joints, and between the reception hall and dining room there are sliding doors.

The fire places on the lower floor are furnished with club-house grates, tile hearths, and cabinet oak mantels.

Upstairs the finish is the same with the exception of mirrors above the mantels. Down stairs, in addition to the halls, dining room, parlor and kitchen, there is an ample pantry, conveniently fitted up with bins and shelves, and a well arranged butler’s pantry with sink. There is a lavoratory [sic] down stairs and up stairs a complete bath room with porcelain-lined bath tub. The plumbing is of the best quality, both in material and workmanship. The three chambers up stairs are connected and each has an ample closet.

At the end of the upper hall there is a large linen closet. The ascent from the first to the second story is by very pretty stairs with a graceful landing divided from the front hall by grill work, as indicated.

The hardware is of fine quality, all the way through, and the finish is old copper. The gas fixtures are furnished with electric lighting apparatus and a complete system of electric bells extends through the house.

The painting is three coat work outside and in, and is first class in material and workmanship. The outside is painted in canary, trimmed in white, a very pretty combination. The house is situated on a large lot, at the corner of Whitehall and McDaniel streets, and has attracted much attention.

The perspective view is taken from the northwest, and shows a very pretty veranda in front of the house. The first and second story floor plans, also represented by illustrations, fully explain themselves.

The house was designed for Miss Wells by Butt & Morris, of Atlanta.11

References

- “Removal.” The Atlanta Constitution, September 10, 1893, p. 16. ↩︎

- “Butt & Morris, Architects”. (advertisement), The Atlanta Journal, May 30, 1896, p. 10. ↩︎

- “Advertisement for Bids for Construction of Stable at the Dumping Grounds.” The Atlanta Constitution, May 16, 1905, p. 15. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1908) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1909) ↩︎

- “Mrs. Eleanor M. Wells Dies Monday Morning”. The Atlanta Journal, January 8, 1906, p. 9. ↩︎

- “For Rent–Houses.” The Atlanta Constitution, January 17, 1906, p. 12. ↩︎

- “Property Transfers.” The Atlanta Constitution, February 2, 1913, p. 8. ↩︎

- “Building Permits”. The Atlanta Journal, November 5, 1912, p. 17. ↩︎

- “Atlanta’s Strides From Day To Day”. The Atlanta Constitution, December 17, 1913, p. 13. ↩︎

- “Journal Model Homes; Residence of Miss Susie Wells” The Atlanta Journal, January 22, 1898, p. 11. ↩︎