Category: Architecture

-

725 Ponce (2019) – Atlanta

S9 Architecture and Cooper Carry. 725 Ponce (2019). Poncey-Highland, Atlanta.1 -

Anniston Inn Kitchen and Dining Hall (1885) – Anniston, Alabama

George T. Pearson. Kitchen and dining hall from Anniston Inn (1885). Anniston, Alabama.1 2 3 References

- National Register of Historic Places Inventory — Nomination Form: Anniston Inn Kitchen ↩︎

- “The Anniston Inn.”Anniston Hot Blast (Anniston, Alabama), May 24, 1884, p. 1. ↩︎

- “The Anniston Inn.” Montgomery Daily Advertiser (Montgomery, Alabama), May 8, 1885, p. 4. ↩︎

-

125 Edgewood Avenue (1889) – Atlanta

G.L. Norrman (attributed). 125 Edgewood Avenue (1889). Atlanta. This small commercial building on the southeast corner of Edgewood Avenue and Courtland Street in Downtown Atlanta would have been demolished long ago if it hadn’t served briefly as the first Coca-Cola bottling plant in the city. For that reason, the structure was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1983.1

Located at 125 Edgewood Avenue SE, the property is rare in Atlanta for maintaining the same numeric address for its entire existence. Local historians have long claimed the building was constructed in either 1890, 1891, or 1892. However, it’s well documented that the structure was built in 1889 and occupied in January 18902 3 — Atlanta is appallingly ignorant of its own history.

The building consists of two floors over a full basement,4 5 and is eclectically styled, incorporating Romanesque and Queen Anne elements. The exterior is covered in red brick with light granite trim, and the interior encompasses less than 6,000 square feet. While the architect is not officially known, all evidence indicates that G.L. Norrman was the designer.

The Design

Anyone with an eye for his work would quickly observe that the overall design and massing of 125 Edgewood Avenue are characteristic of Norrman, and many specific elements also suggest his involvement:

- The oval window in the north gable was used by Norrman in multiple projects around the same time, including the Samuel McGowan House (1889) in Abbeville, South Carolina; the Atlanta & Edgewood Street Railway Shed (1889) and 897 Edgewood Avenue (1890) in Inman Park, and most notably, the nearby Exchange Building (1889, pictured below).

- Chimneys with tapered tops were a trademark element of Norrman’s in the 1880s and 1890s, and the same chimney designs were used in his 1889 plan for the H.M. Potts House (demolished) in Atlanta’s West End.

- The central chimneystack on the north side of the building serves as a focal point to visually balance the elevation’s two incongruent halves — this was a common technique used by Norrman in his compositions.

- A terracotta scroll bracket on the central chimneystack is of the same design as those used in Norrman’s designs for the Windsor Hotel (1892) in Americus, Georgia, and the Edgewood Avenue Grammar School (1892) in Atlanta.

- The stepped gables on the north and west sides of the building were incorporated in Norrman’s design for the nearby Exchange Building and later used on the Windsor Hotel.

- The Romanesque granite column on the northwest corner of the ground floor is a smaller version of one used in Norrman’s design for the Printup Hotel (1888) in Gadsden, Alabama.

- The porch on the west side of the building uses the same posts with curved brackets seen in Norrman’s design for the E.A. Hawkins House (1890) in Americus, Georgia, and the house at 897 Edgewood Avenue in Inman Park.

- The fish-scale shingles used in both the turret and balcony were incorporated into Norrman’s designs for the McGowan House, and the T.P. Ivy House (1895) in Atlanta, among others.

- The most obvious design clue is the square turret on the building’s northwest corner, which is a duplicate of one Norrman used in the H.M. Potts House the same year.6

G.L. Norrman. H.M. Potts House (1889, demolished). West End, Atlanta.7 The Background

The building at 125 Edgewood Avenue was one of at least three commercial spec structures built along Edgewood Avenue by Joel Hurt‘s East Atlanta Land Company — it appears Norrman designed all of them.

Norrman was a preferred architect for Hurt in the late 1880s and early 1890s, with four confirmed projects for Hurt’s companies and family, and four additional structures that can be attributed to him. He was also one of the opening-day tenants in Hurt’s Equitable Building (completed in 1892 and demolished in 1971), occupying a suite of offices on the top floor.8

The full list of Norrman’s completed projects for the Hurt companies and family follows:

- Exchange Building, completed 18899 and demolished 193910 11 – intersection of Edgewood Avenue and Gilmer Street, Atlanta [Map]

- 125 Edgewood Avenue, completed 1889 [Map] – design attributed to Norrman

- Commercial building, completed 1892 and demolished 1939 – 161-165 Edgewood Avenue, SW corner of Edgewood and Piedmont Avenues, Atlanta [Map] – design attributed to Norrman

- Three spec houses for the East Atlanta Land Company

- Atlanta & Edgewood Street Railway Shed, completed 1889 – 963 Edgewood Avenue NE; Inman Park, Atlanta [Map] – design attributed to Norrman

- C. D. Hurt House, completed 1893 – 36 Delta Place; Inman Park, Atlanta [Map] – design attributed to Norrman

G.L. Norrman. Exchange Building (1889, demolished 1938). Atlanta.12 The Beginning of Edgewood Avenue

The East Atlanta Land Company created Edgewood Avenue to serve as the main artery from Atlanta’s commercial district to the company’s suburban residential development, Inman Park.13

Joel Hurt was, by all accounts, a miserable bastard. He was also filthy rich, so of course, he felt entitled to receive whatever he wanted, running to the local press — often his sympathetic friends at The Atlanta Constitution — to whine petulantly when local leaders didn’t bow to his incessant demands.

In 1886, Hurt and his associates began pestering the city council to widen and extend an existing road called Foster Street,14 15 16 17 18 which ran from Atlanta’s Calhoun Street (later Piedmont Avenue) to the foot of Hurt’s 75-acre property near the Air-Line Railroad (later Belt Line Railroad).

Hurt also wanted the city to extend Foster Street from Calhoun Street westward to Ivy Street (later Peachtree Center Avenue), connecting it with another thoroughfare called Line Street (later Hurt Plaza), ending at the Five Points intersection in the center of the city.

Part of what made the scheme so contentious was that Hurt demanded the city of Atlanta use eminent domain to remove homes and buildings along the route.

The city council initially rebuffed Hurt’s proposal in June 1886,19 but mysteriously reversed course and approved it in August 1886.20 21 Hurt formed the East Atlanta Land Company the following year, with the expressed intention of developing his 75-acre estate and “building a street car line down Foster Street to the Boulevard and on through this suburban property.”22

Hurt’s demands for the project kept growing, and following nearly two years of discussion and revisions, the City of Atlanta and the East Atlanta Land Company finally settled on a deal, the details of which are too tedious to elaborate on.

Ultimately, both parties funded the construction of the street, while Hurt agreed to give ownership to the city, which, in turn, agreed to condemn any property or building along the route that Hurt’s company couldn’t purchase or remove through its own negotiations with property owners.23 24 25 26 27 28

As the project was underway, Foster Street was renamed Edgewood Avenue, which the Constitution described as “A Pretty Street with a Pretty Name…And the Men Who Made It Are Also Very Pretty, Etc. Etc.”29 So much for objective journalism.

Vintage photograph of Joel Hurt30 It should come as no surprise that the area cleared for Edgewood Avenue was largely inhabited by poor and Black residents, a foreshadowing of Atlanta’s widespread clearance of low-income areas for freeways in the 1950s and 60s, the largest act of wholesale destruction in the city’s history (no, it wasn’t Sherman).

For their part, local newspapers had nothing but praise for Hurt’s project. In 1888, the Constitution predictably gushed:

“The objectionable houses that stood on Line Street have been torn down and now Edgewood avenue runs over the very spot where they once stood. The tearing down of these old houses and removing them from the heart of the city is an act the city should thank the company for.”31

“Objectionable houses,” incidentally, was a polite euphemism for brothels.

The Macon Telegraph was a little more explicit, explaining that the brick houses on Line Street “were once notorious resorts”, and that “the inmates [have] been required to move on to Collins Street” (later Courtland Street),32 which became Atlanta’s red-light district.

In a speech from September 1888, Hurt revealed the extent of the clearance:

“We have conducted negotiations with one hundred and thirty two property owners … it has been necessary to condemn the properties of about thirty parties. It has been necessary to move ninety buildings…We have destroyed $70,000 worth of brick and stone buildings alone.”33

Buried in the same speech was the following note:

“There are four properties of private individuals and one of the Atlanta street railroad company, extending slightly in the street, and at these points work has been delayed because of legal difficulties.”34

If Hurt’s description feels conveniently sanitized, a lawsuit filed by a property owner on Edgewood Avenue hints at the true contentious nature of the project.

In September 1888, Dennis F. O’Sullivan sued the East Atlanta Land Company for its seizure and destruction of his property on Edgewood Avenue.35 O’Sullivan alleged that the company “took forcible possession of [his] premises, moved two of his houses a considerable distance…and then filled in a strip of land…making it higher than the other part of his property, so that water collects there as in a basin.”

O’Sullivan additionally sued the City of Atlanta, because he claimed that he was “prevented by interfering from the police.” Cops defending monied interests? Shocker.

By the time Edgewood Avenue formally opened on September 26, 1888,36 the East Atlanta Land Company owned most of the property along the 2-mile route, which was accurately described as “the only perfectly straight street of any length in the city,”37 running from Five Points to Inman Park.

Hurt’s Atlanta & Edgewood Street Railroad Company (better known as the A&E) became the first electric street railway in Georgia when it debuted on August 22, 1889.38 Running on double tracks, the “new-fangled street car”39 glided at a cool 18 miles per hour40 along Edgewood Avenue, which city workers finished paving with Belgian block just four days earlier.41

North elevation of 125 Edgewood Avenue Construction and History

Two weeks before the trolley’s debut, the building permit for 125 Edgewood Avenue was issued in early August 1889, with construction supervised by B.R. Padgett,42 a prolific contractor who in later years marketed himself as an architect (he wasn’t). Construction on the project was swift, with only four months from the date the permit was issued to the building’s opening.

Joel Hurt regularly employed convict labor in his civic projects, and chain gangs loaned by Fulton County were used in the construction of Edgewood Avenue.43 However, Hurt’s nearby Exchange Building was built with paid day labor,44 and 125 Edgewood was likely completed in the same manner.

Even if convicts didn’t work on the building, its distinctive red-clay bricks were almost certainly manufactured by the Chattahoochee Brick Company near Atlanta, which also ran on forced prison labor.45

Open House

Hanye Grocery Company was 125 Edgewood’s first tenant, opening on the ground floor in January 1890. Advertising itself as “The Prettiest Store and most Complete Grocery House in the South”, and “the finest this side of Baltimore, without any exaggeration”, the store purportedly offered “the finest fancy and domestic goods”.46

The store’s owner was R.M. Hanye, who moved his grocery business from a smaller space on Decatur Street. “I cordially invite the ladies to visit my grocery in the magnificent new brick building…”, Hanye proclaimed in newspaper ads.47

The new store was described as “palatial” by The Atlanta Journal, which noted the “three handsome double entrances” and marveled that “A person can enter the door at one end of the store and walk to the other end, taking a good view of the entire stock, and come out at the further entrance on the same street (Edgewood avenue.)”48

Unique for Atlanta, the building was designed so that the business proprietor could reside in the residential space above the store, accessed from Courtland Street by the porch built halfway between the first and second floors.

The concept even received national attention: An 1890 article in Architecture and Building mentioned Norrman’s similar design for the nearby Exchange Building, reporting, “A novel scheme for utilizing a triangular corner lot was evolved by Mr. Norrman, giving two residences over a store.”49

In 125 Edgewood, it appears the second-floor living space consisted of two large rooms and a bathroom, which were quickly divided into one-room apartments, based on a description in a 1896 advertisement.50 According to city directories from 1890 and 1891, Hanye both lived and worked in the building,51 52 although future tenants in the retail space lived off-site.

The Hanye Grocery Company was officially incorporated in July 1890,53 with Joel Hurt listed as one of the owners.54 A hand-painted sign advertising the grocery is still faintly visible on the east side of the building, although it has long outlasted the business.

R.M. Hanye sign on the east elevation of 125 Edgewood Avenue In 1891, the Hanye Grocery Company reincorporated itself — without Hanye or Hurt — as the Atlanta Grocery Company,55 which closed by 1893, replaced by Hosch & Son grocers.56 In 1894, the space was occupied by yet another grocery, operated by Mrs. F.A. Holleran.57

From 1895 to 1898, 125 Edgewood Avenue housed Star Grocery, operated by John M. Waddill,58 59 60 and in 1895, the building also briefly contained a photography studio operated by Hugh Schmidt.61 62 In 1899, the building was vacant.63

The essential problem with the building’s location was already apparent in 1890, when Hanye’s ads stressed that his store was “Only three minutes’ ride on the Atlanta and Edgewood electric cars.”64 It was simply too far from the heart of Atlanta’s commercial district, primarily centered 3 blocks west at the intersection of Whitehall, Decatur, and Marietta Streets.

The East Atlanta Land Company clearly hoped that the building’s tenants would capture the business of trolley riders shuttling to and from Inman Park, yet, despite a wide-scale promotional blitz, early home sales in Inman Park were anemic.

Many of the giant spec houses planned by Atlanta’s leading architects sat empty for years or were rented out before Inman Park was swallowed up by the encroaching city and filled with smaller, cheaper homes in the early 20th century.

Peachtree Street remained the preferred address of the city’s elite for at least 20 years after Inman Park’s opening, and for the old-money families of Atlanta (whatever that meant in a 53-year-old city), the suburb could only have been viewed as a gauche, far-out enclave for the nouveau riche.

Stepped gable on the north elevation of 125 Edgewood Avenue The Coca-Cola Year

Beginning circa April 1900,65 the Dixie Coca-Cola Bottling Company occupied 125 Edgewood for about 8 months, a tenancy so short-lived that the company’s presence isn’t even listed in city directories from the time, although newspaper classified ads confirm it.

One such ad requested: “Three boys about 17 to do rough light work; must be hustlers and willing to work cheap.”66 No comment necessary.

Typical of most Atlanta enterprises, Coca-Cola’s origins are shady and convoluted, but the product first debuted in 1886 as a medicinal tonic at Jacobs’ Pharmacy on Marietta Street, and steadily gained regional and national popularity as an alternative to alcohol when Atlanta and other cities began dabbling in prohibition. “The proper use of it will make a drunken man sober,” the ever-truthful Constitution claimed.67

In 1898, Coca-Cola opened new headquarters one block east of 125 Edgewood Avenue at the intersection of Edgewood and College Street (later named Coca-Cola Place), with a 3-story brick building designed by Bruce & Morgan and owned by the East Atlanta Land Company. 68 69 70 71

An important distinction to make is that it wasn’t the Coca-Cola Company that operated from 125 Edgewood Avenue, but an entirely separate bottling company licensed to distribute Coca-Cola’s product in the Southeast.72

Contrary to Coke’s corporate mythmaking, the company has long been a stodgy, insular, and conservative entity with a flair for empty self-promotion — not unlike Atlanta itself. In Coca-Cola’s early years, the beverage could only be purchased at soda fountains, and the company’s president, Asa G. Candler, didn’t see the value in bottling his product.

In 1899, Candler reluctantly agreed to grant bottling rights to J.B. Whitehead and B.F. Thomas, who subsequently established the Dixie Coca-Cola Bottling Company to distribute the soda throughout the Southeast. Starting their first bottling plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, the men then opened a second plant at 125 Edgewood in Atlanta.73

In 1900, Coca-Cola reportedly sold 51,147 gallons in Atlanta 74 — that appears to be separate from the product bottled at 125 Edgewood, and it’s unclear how much was distributed from the building, but it couldn’t have been substantial. The plant’s output was limited by the size of its marketing territory, which was reportedly measured by how far a mule team could travel in a day.75

By January 1901, the Dixie Coca-Cola plant vacated 125 Edgewood and moved to 35 Ivy Street.76

In truth, Coke’s connection with 125 Edgewood is barely worth noting, but Atlanta has destroyed so much of its history that it has to cling to whatever remnants it can to pretend it has a cultural legacy beyond hype, moneymaking, and oppression.

After Coca-Cola

It’s also unclear when the East Atlanta Land Company sold 125 Edgewood, but with the failure of Inman Park and other projects, coupled with the severe financial depression of the mid-to-late 1890s, the company shed its assets in multiple auctions over the next decade.

Hurt seemingly lost interest in the company as he threw his energy and attention into the management of the Atlanta Consolidated Street Railway Company, formed in 1891 by the merger of the A&E and 5 other street railway companies,77 78 as well as the establishment that same year of the bank that would become the Trust Company of Georgia.79

The East Atlanta Land Company auctioned off the bulk of its Edgewood Avenue commercial property in 1903 80 81 82 83— including its property on Exchange Place and the Coca-Cola headquarters84 — followed by a final sale of its remaining assets in 1906.85 86 87 88 89 It appears that 125 Edgewood was likely sold in 1903, as the property wasn’t listed in the 1906 auction.90

Looking at 125 Edgewood Avenue from the northeast For the next 20 years, 125 Edgewood hosted a revolving door of short-lived businesses:

- In December 1901, a grocery store operated by a man named Charles with the last name of either Charalambedis, Charalambitis,91 or Charalampe92 declared bankruptcy, selling a “stock of groceries and fixtures…including counters, show cases, and two soda founts…”93

- In May 1902, an entirely different grocery store, operated by I. Goldberg, also declared bankruptcy, selling its stock of “staple and fancy groceries fresh and in good condition, show cases, computing scales, coffee mill and other fixtures usually belonging to such business”.94

- In 1903, the space was occupied by L.C. Johnson and Company, described as “retail grocers and restaurant”.95

- In 1904, a cigar business owned by Henry I. Palmer was listed at the address.96

- In October 1904, a drug store at the location went into receivership, selling off “one stock of drugs and fixtures, stock bottles and show cases, one soda fount and all attachments; also one carbonator, filler, and Crown machine, almost new”. The store was advertised as “A splendid opportunity for a live young man.”97

- A drug store operated by George C. Mizell operated at the address in 1905.98

- In 1906, the ground floor of the building was occupied by Central Pharmacy, with Virgil A. Jones, a barber, on the second floor.99 In January 1906, a “12-syrup soda fount, A1 condition, cheap, if sold at once”, was advertised at the address.100

- Central Pharmacy was still in business in 1907, operated by Henry F. Askam, although the barber shop was replaced by a “pressing club” operated by John R. Thomason.101

- By 1908, Central Pharmacy had become the Askam & Alford pharmacy, operated by Askam with N.E. Alford.102 The business was again called Central Pharmacy in 1909.103

- In 1909, J.B. Peyton applied for a transfer of a near-beer license at the address from J. Bigler.104 Georgia enacted Prohibition in 1907, so saloons at the time only served non-alcoholic beverages. Ahem.

- Peyton’s saloon was still in operation in 1910, occupying the ground floor,105 but Peyton transferred the license to George N. Weekes in December 1910.106 That year, the top-floor apartment was occupied by two men: James Lindsey and William T. Culbreath.107

- In 1911, the structure was owned by the Adair family’s local real estate empire, and a building permit was issued for $220 in fire damage repair.108

- In 1912, the building housed another saloon, operated by William T. Murray.109

- From 1913 to 1916, a saloon and pool room operated by Louis Silverman was located in the building,110 111 112 113

- In 1917, the Turman & Calhoun real estate company advertised the building’s “clean storeroom”, noting it was “within three minutes of Peachtree”.114

- Directories from 1918 list the building space as vacant,115 but by August of that year, the building housed the Atlanta Screen and Cabinet Works, owned by J.W. Biggers.116

- In 1920 and 1921, the space was occupied by a dry goods store operated by Harris Roughlin.117 118

- In 1922, the Mazliah & Cohen dry goods store operated in the space,119 and by 1923, it had been replaced with a dry goods store owned by Joe Horwitz.120

- In 1924, a “well-established millinery business” at the address was listed for sale.121

Ground floor window on the northeast corner of 125 Edgewood Avenue The Briscoe-Morgan Murder-Suicide

The ground-floor space at 125 Edgewood was occupied by B. and B. Clothing Company122 — a store owned by J.W. Biggers of Atlanta Screen and Cabinet Works fame — when it was the scene of a murder-suicide in 1924.123 124

On August 7, 1924, Fannie Briscoe, a 36-year-old saleswoman at the business, was shot to death by W.R.L. Morgan, a 52-year-old insurance salesman who had reportedly been in a relationship with Briscoe. Immediately after killing her, Morgan turned the pistol around and shot himself in the head, “falling dead at Mrs. Briscoe’s feet.”125

The scene was witnessed by a man repairing his tire outside the store, who reported that Briscoe screamed “Don’t do that! Don’t do that” in the moments before she was killed.126

Newspapers at the time described a typical Atlanta romance: Briscoe had divorced her first husband and was separated from her second when she began a relationship with Morgan. The two “became infatuated with each other” and lived together in an apartment on Pryor Street, but had recently broken up.127

A police investigator explained that “Morgan’s mind seemed to have become somewhat unbalanced following this separation and he became deeply depressed at times.”128

Three letters found in Morgan’s pocket addressed various aspects of post-mortem business, with such tedious and clichéd phrasing as: “I am tired of life. The world has gone back on me.”

Apparently fond of morose prose, Morgan left another letter in his apartment, in which he moaned: “Fannie Briscoe is the cause of it all. I can’t stand the way she has done me. That’s all. Good by to all.”129

Even in death, Atlantans are narcissistic and boring.

Stepped gable on the west elevation of 125 Edgewood Avenue Crime and Seediness

Early claims that Edgewood Avenue would “attract the rich and fashionable to live upon it”130 were pure Atlanta bullshit, and while never a prestige address, it’s clear that 125 Edgewood quickly became just as seedy and crime-ridden as the properties demolished for the street’s construction a few years earlier.

Recall that in 1889, the “inmates” of the former Line Street had simply been pushed over to Courtland Street, so of course, the location was destined to draw an unsavory element.

In October 1906, the building’s second floor was raided by police for housing an illegal gambling establishment. Twelve men were arrested during a game of poker,131 in which “it was found necessary to break in one or two doors”, according to the Journal, which added: “it is said that Sergeant Lanford swung a sledge hammer like a veteran blacksmith.”132

In 1916, Louis Silverman, the proprietor of a pool room and saloon in the building, was ordered to appear in court for allowing minors to play,133 apparently leading to the closure of the business.

In 1924, less than a month after the murder-suicide, the B. and B. Clothing Company was robbed of a satin dress.134

In 1925, the space housed a store operated by Morris Jackson, which was robbed in an overnight burglary that resulted in the loss of 15 dozen pairs of hosiery, 13 shirts, 12 pairs of suspenders, and 23 necklaces.135

In September 1928, the building was occupied by the Atlas Dry Goods Store when it was robbed again — this time of 20 dresses. 136 Three months later, the store’s “show window” was smashed in during an overnight robbery attempt.137

One 1982 article from the Constitution said of the property: “There is even evidence to suggest that, at one down-at-the-heels juncture in its past, the second story was a house of ill repute disguised as a boarding home.”138 The mind boggles.

Squared corner turret on 125 Edgewood Avenue Occupants in the Mid-20th Century

Following the 1924 murder-suicide, 125 Edgewood hosted a few more short-lived businesses, although occupancy at the location stabilized through mid-century:

- In October 1925, a “candy kitchen, fully equipped” was auctioned off at the location.139

- In December 1925, a restaurant owned by O.G. Hughes operated from the building, where his 2-year old son was severely scalded by a pot of boiling water.140 141

- The Warner Heating and Plumbing Company operated from the building, circa 1930-1936.142 143

- A shop selling “sandwiches and drinks, doing nice business” with “low rent” was advertised in the Business Opportunities section of theConstitution classifieds in 1935.144

- The Shepard Decorating Company was owned by Virgil W. Shepard, who bought the building from the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company in 1939145 and operated the business at the location until 1951.146 147 148

- Brown Radio Sales & Service, a Philco dealership, operated at 125 Edgewood from 1952 to 1969.149 150

Ground floor window on the north side of 125 Edgewood Avenue Reassessment

After years of neglect, in 1966,151 the Atlanta Baptist Association purchased 125 Edgewood with plans to demolish it, but when Georgia State University identified the property as one it intended to include in its campus expansion plans, the organization instead kept the building to sell to the university.152

While it waited for Georgia State to purchase the property, in 1969, the association opened the Baptist Student Union at 125 Edgewood.153 You gotta stash the kids somewhere, right? What started as a temporary tenancy became the building’s longest occupancy.

Georgia State abandoned its plan to purchase 125 Edgewood circa 1976, when the building was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places.154

In 1978, the building was additionally nominated as a National Historic Landmark. The Historic Preservation Section of Georgia’s Department of Natural Resources submitted the nomination,155 citing the building’s connection to Coca-Cola, although the company’s executives — esconced in their dreary concrete fortress on North Avenue — apparently wanted nothing to do with it.

“The Coca-Cola people weren’t overjoyed by the nomination,” recalled a historian from the DNR, adding: “Perhaps they didn’t want such a tacky little building representing them.”156

A Coca-Cola spokesperson responded with bland corporate diplomacy: “I don’t think we would object to it being on the list, but I don’t think we would have pushed it either.”157 Is it any wonder Atlanta never saves a damn thing?

Second-story windows on the north elevation of 125 Edgewood Avenue Constricted by the building’s new historic designations, the Atlanta Baptist Association decided to renovate 125 Edgewood, which by the early 1980s was in a visible state of disrepair but described as “extremely sound.”158

Photographs from 1976 reveal the many alterations that occurred over the years: the building’s brick facade had been painted, the corner windows on the ground floor were boarded over, and the original porch and balcony had been removed.

“One of the things about the building is that it looks like it’s not occupied,” explained one of the student union’s leaders. “You can walk by and think no one’s here.”159

A renovation and expansion plan was completed in 1980 by Cavender/Kordys Associates Inc.,160 a small architectural firm from nearby East Point, Georgia.161 The firm estimated the project would cost $475,000, and the association began a fundraising campaign to pay for it.162

By 1987, the renovation had yet to begin, and the building’s structural integrity had so deteriorated that it was reported to the United States Congress as a Threatened National Historic Landmark.163

Renovation and Addition

Renovation on 125 Edgewood finally proceeded in 1989,164 165 including a reconstruction of the porch and a shortened version of the second-floor balcony, using a 1893 photograph of the building as a design reference.166

The building’s windows were replaced with recreations of the originals, the paint was removed from the brick, and the broken chimneystack on the north side was rebuilt.

For the modern addition, a small, unobtrusive wing was attached to the south side of the building, designed with matching brick and granite stringcourses to complement the historic structure while providing the student union with extra space.

The project restored the building’s outer shell, but no attempt was made to restore the interior to its former appearance — the original stairwells were ripped out, walls were removed to create open meeting space, and the ceilings were covered in standard 1980s acoustic tile.

A 2003 update to the building’s landmark nomination form explained that the renovation, combined with 100 years of previous interior changes, had “altered the original floor plan to where it is virtually indiscernible.”167

Reconstructed porch on the west elevation of 125 Edgewood Avenue Return to Dilapidation

Atlanta abhors maintaining its historic buildings — or anything, for that matter — and in the early 21st century, 125 Edgewood again shows signs of long-term neglect.

Visible issues in 2025 included a broken window in the corner turret covered with a flimsy tarp, rotting wood on the porch and balcony, missing shingles, and a mysterious dark stain running down the side of the porch. Images from the same year revealed the interior’s dilapidated state, including major flooding in the basement.168

Nearly 60 years after it moved into the building, in December 2024, the BCM at Georgia State (formerly the Baptist Student Union) vacated 125 Edgewood,169 and the property was placed for sale, marketed as ‘one of the last “true” relatively untouched Victorian mansions left downtown’,170 an erroneous statement in every conceivable fashion. The building is currently abandoned.

An Uncertain Future

As of 2026, the future of 125 Edgewood Avenue is anything but certain.

The building’s National Historic Landmark status doesn’t amount to much, as proven by Atlanta University Center’s Stone Hall (1882), also designed by Norrman and designated as a National Historic Landmark. Abandoned in 2003, Stone Hall has been heavily vandalized and in a state of rapid deterioration for years, with no meaningful funding or plans to return it to viable use.

Because 125 Edgewood is designated as a City of Atlanta Landmark, the structure is well protected from demolition,171 but it’s unclear how the building could be suitably repurposed, as it’s too small and poorly positioned for a public-facing business.

Parking at the location is also limited, and Atlantans value their vehicles more than their lives, so if a business isn’t within feet of cheap, abundant parking, it has no chance of survival.

The building appropriately sits on the route for the revived Atlanta Streetcar, although that, too, doesn’t count for much. Atlanta’s streetcar is an absolute failure of a vanity project that’s barely used by anyone — that is, if it’s even running at all.

The one certainty about the property is this: despite its unique design and historic significance, 125 Edgewood has never been a good place for a business.

Looking at 125 Edgewood Avenue from the west References

- National Historic Landmark Nomination: Dixie Coca-Cola Bottling Company Plant ↩︎

- “The City Council.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 6, 1889, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Georgia’s Prettiest”. The Atlanta Journal, January 14, 1890, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Miscellaneous.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 28, 1895, p. 9. ↩︎

- National Historic Landmark Nomination: Dixie Coca-Cola Bottling Company Plant ↩︎

- “Society Gossip.” The Atlanta Constitution, October 9, 1889, p. 4. ↩︎

- “West End.” The Atlanta Constitution, April 27, 1890, p. 21. ↩︎

- “In the Equitable.” The Atlanta Constitution, May 31, 1892, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Home Building.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 20, 1889, p. 8. ↩︎

- “Old City Hall Site Exchange Effective April 15”. The Atlanta Journal, April 10, 1939, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Mayor Requests $25,000 Gifts For Auditorium Park”. The Atlanta Constitution, August 30, 1939, p. 9. ↩︎

- Carson, O.E. The Trolley Titans: A Mobile History of Atlanta. Glendale, California: Interurban Press (1981). ↩︎

- “Building a Suburb”, The Atlanta Constitution, November 6, 1887, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Important Petition.” The Atlanta Journal, February 1, 1886, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Opening a New Street.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 24, 1886, p. 7. ↩︎

- “To Meet Tomorrow.” The Atlanta Constitution, April 21, 1886, p. 7. ↩︎

- “The Aldermanic Board.” The Atlanta Journal, May 6, 1886, p. 1. ↩︎

- “The Board of Aldermen.” The Atlanta Constitution, May 7, 1886, p. 7. ↩︎

- “The Foster Street Extension.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 8, 1886, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Our City Legislature.” The Atlanta Journal, August 3, 1886, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Aldermanic Board.” The Atlanta Journal, August 5, 1886, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Another Grand Enterprise.” The Atlanta Journal, May 9, 1887, p. 4. ↩︎

- “A Liberal Offer.” The Atlanta Constitution, February 7, 1888, p. 8. ↩︎

- “The Foster Street Extension.” The Atlanta Constitution, February 17, 1888, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Foster Street.” The Atlanta Constitution, February 18, 1888, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Foster Street.” The Atlanta Constitution, February 19, 1888, p. 14. ↩︎

- “Whisky and Streets”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 21, 1888, p. 5. ↩︎

- “They All Like It.” The Atlanta Constitution, February 22, 1888, p. 5. ↩︎

- “The New Avenue”. The Atlanta Constitution, September 5, 1888, p. 5. ↩︎

- Marr, Christine V. and Sharon Foster Jones. Inman Park. Arcadia Publishing: Charleston, South Carolina, 2008. ↩︎

- “Building.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 16, 1888, p. 22. ↩︎

- “Clearing Away Houses.” The Macon Telegraph, August 2, 1888, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Building.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 16, 1888, p. 22. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “About the Steps.” The Atlanta Constitution, September 6, 1888, p. 5. ↩︎

- “The New Street.” The Atlanta Constitution, September 27, 1888, p. 7. ↩︎

- “We, Us and Co.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 14, 1887, p. 4. ↩︎

- Carson, O.E. The Trolley Titans: A Mobile History of Atlanta. Glendale, California: Interurban Press (1981), p. 12. ↩︎

- “For Inman Park.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 21, 1889, p. 8. ↩︎

- “Electric Street Cars.” The Atlanta Journal, April 13, 1889, p. 2. ↩︎

- “Changing Atlanta.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 18, 1889, p. 16. ↩︎

- “The City Council.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 6, 1889, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Through the City”. The Atlanta Constitution, April 30, 1888, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Home Building.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 20, 1889, p. 8. ↩︎

- “The City Council.” The Atlanta Constitution, April 20, 1886, p. 5. ↩︎

- “The Grocery” (advertisement). The Atlanta Journal, January 23, 1890, p. 3. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Georgia’s Prettiest”. The Atlanta Journal, January 14, 1890, p. 7. ↩︎

- Boorman, T.H. “Through Georgia.” Architecture and Building, Volume 13, No. 1 (July 5, 1890), p. 8. ↩︎

- “ROOMS — Furnished or Unfurnished.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 27, 1896, p. 23. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1890) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1891) ↩︎

- “The Hanye Company.” The Atlanta Constitution, July 1, 1890, p. 2. ↩︎

- Legal notice. The Atlanta Journal, June 4, 1890, p. 7. ↩︎

- “In the Courts.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 10, 1891, p. 8. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1893) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1894) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1896) ↩︎

- “Miscellaneous.” (advertisement) The Atlanta Constitution, March 28, 1895, p. 9. ↩︎

- “Red Trading Stamps.” (advertisement) The Atlanta Journal, June 17, 1898, p. 11. ↩︎

- “Wanted — Help — Female.” (advertisement) The Atlanta Journal, August 17, 1895, p. 11. ↩︎

- “Instruction.” (advertisement) The Atlanta Constitution, September 15, 1895, p. 22. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1899) ↩︎

- “The Grocery” (advertisement). The Atlanta Journal, January 23, 1890, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Coca-Cola Carbonated.” The Atlanta Constitution, April 8, 1900, p. 9. ↩︎

- “HELP Wanted–Male.” (advertisement) The Atlanta Constitution, July 6, 1900, p. 9. ↩︎

- “The Story of Coca-Cola”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 20, 1901, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Lights and Shades.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 9, 1898, p. 9. ↩︎

- “Coca Cola Company Begins New Building”. The Atlanta Journal, March 18, 1898, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Many Visitors Present.”The Atlanta Constitution, December 14, 1898, p. 11. ↩︎

- “Coco-Cola Building Has Been Opened”. The Atlanta Journal, December 15, 1898, p. 12. ↩︎

- National Historic Landmark Nomination: Dixie Coca-Cola Bottling Company Plant ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “The Story of Coca-Cola”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 20, 1901, p. 4. ↩︎

- Walker, Tom. “Coca-Cola Bottling: 75

Refreshing Years”. The Atlanta Journal, July 25, 1975, p. 3-C. ↩︎ - “Lost.” (advertisement) The Atlanta Constitution, January 5, 1901, p. 6. ↩︎

- “The Deal Closed.” The Atlanta Constitution, March 15, 1891, p. 20. ↩︎

- “Articles of Incorporation”. The Atlanta Journal, April 10, 1891, p. 3. ↩︎

- Carson, O.E. The Trolley Titans: A Mobile History of Atlanta. Glendale, California: Interurban Press (1981). ↩︎

- “Central Lots Will Be Sold”. The Atlanta Constitution, April 6, 1903, p. 2. ↩︎

- “Big Real Estate Sale”. The Atlanta Journal, April 10, 1903, p. 14. ↩︎

- “Central Lots Bring High Figures”. The Atlanta Journal, April 21, 1903, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Edgewood Avenue Lots Bring Good Prices”. The Atlanta Journal, April 22, 1903, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Over Seven Acres Central Property At Auction Tuesday”. The Atlanta Journal, April 19, 1903, p. 9. ↩︎

- “Forrest and George Adair Edgewood Avenue Property For Sale” (advertisement). The Atlanta Journal, April 15, 1906, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Edgewood Avenue Property” (advertisement). The Atlanta Constitution, May 26, 1906, p. 12. ↩︎

- “Real Estate For Sale By Adair.” (advertisement) The Atlanta Constitution, June 3, 1906, p. 5. ↩︎

- “For Sale–Real Estate.” The Atlanta Journal, June 7, 1906, p. 14. ↩︎

- “Real Estate For Sale By Adair”. The Atlanta Constitution, June 10, 1906, p. 10. ↩︎

- “Forrest & George Adair–Auctioneers” (advertisement). The Atlanta Constitution, June 10, 1906, p. 8. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1902) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1900) ↩︎

- “Bankrupt Sale”. (advertisement) The Atlanta Journal, December 28, 1901, p. 11. ↩︎

- Legal notice. (advertisement)The Atlanta Journal, May 9, 1902, p. 11. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1903) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1904) ↩︎

- “Receiver’s Sale”. (advertisement) The Atlanta Journal, October 15, 1904, p. 13. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1905) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1906) ↩︎

- “For Sale–Miscellaneous” (advertisement). The Atlanta Journal, January 25, 1906, p. 17. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1907) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1908) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1909) ↩︎

- “Miscellaneous” (advertisement).The Atlanta Journal, December 14, 1909, p. 18. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1910) ↩︎

- “Miscellaneous” (advertisement).The Atlanta Journal, December 16, 1910, p. 21. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1910) ↩︎

- “Building Permits.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 2, 1911, p. 15. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1912) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1913) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1914) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1915) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1916) ↩︎

- “For Rent–Stores” (advertisement).The Atlanta Journal, October 1, 1917, p. 14. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1918) ↩︎

- “Carpenter Shop.” (advertisement)The Atlanta Constitution, August 1, 1918, p. 11. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1920) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1921) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1922) ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1923) ↩︎

- “Business Opportunities” (advertisement). The Atlanta Journal, May 23, 1924, p. 34. ↩︎

- “Shoots Woman And Then Kills Self In Atlanta Store”. The Atlanta Journal, August 7, 1924, p. 1. ↩︎

- “W.R.L. Morgan Fatally Wounds Woman He Loved”. The Atlanta Constitution, August 8, 1924, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Atlantian Shoots Woman to Death and Kills Himself”. The Atlanta Journal, August 9, 1924, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Funeral Services Today for Victims of Double Killing”. The Atlanta Constitution, August 9, 1924, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Hunt for Double Motive In Killing Dropped By Police”. The Atlanta Journal, August 8, 1924, p. 12. ↩︎

- “Funeral Services Today for Victims of Double Killing”. The Atlanta Constitution, August 9, 1924, p. 4. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Hunt for Double Motive In Killing Dropped By Police”. The Atlanta Journal, August 8, 1924, p. 12. ↩︎

- “H.L. Wilson, — Auctioneer” (advertisement). The Atlanta Constitution, May 13, 1888, p. 20. ↩︎

- “Is Atlanta Again to Open Doors to the Professional Gamblers Using Queer Cards and Dice?” The Atlanta Constitution, October 21, 1906, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Gaming House Is Raided By Police”. The Atlanta Journal, October 16, 1906, p. 1. ↩︎

- Police Plan to Ban All Minors From Pool Rooms”. The Atlanta Journal, July 2, 1916, p. 12. ↩︎

- “Gems Worth $1,500 Taken From Jeweler’s Home in Druid Hills”. The Atlanta Journal, September 3, 1924, p. 11. ↩︎

- “Burglars Reap Rich Harvest in Clothing; Tire Thieves Flourish”. The Atlanta Journal, March 13, 1925, p. 38. ↩︎

- “Atlanta Burglars Get Tough Breaks On Decatur Street”. The Atlanta Journal, September 19, 1928, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Radio Set Is Taken In Burglary at Home”. The Atlanta Journal, December 26, 1928, p. 16. ↩︎

- Bailey, Sharon. “GSU Baptist students have hopes to restore 1891 Victorian structure.” The Atlanta Journal, December 19, 1982, p. 43. ↩︎

- “Financial” (advertisement). The Atlanta Journal, October 18, 1925, p. F3. ↩︎

- “Small Boy Scalded By Boiling Water”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 26, 1925, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Boy, 2, Badly Scalded”. The Atlanta Journal, November 26, 1925, p. 2. ↩︎

- Advertisement. The Atlanta Journal, May 1, 1930, p. 4. ↩︎

- Advertisement. The Atlanta Journal, August 16, 1936, p. 41. ↩︎

- “Business Opportunities”. The Atlanta Constitution, April 7, 1935, p. 23. ↩︎

- “Sales of $70,959 for Adams-Cates”. The Atlanta Constitution, April 16, 1939, p. 12. ↩︎

- “Employment” (advertisement). The Atlanta Constitution, March 30, 1943, p. 18. ↩︎

- “Household Goods”. The Atlanta Journal, May 29, 1947, p. 26. ↩︎

- Shepard Decorators, Inc. advertisement. The Atlanta Journal, August 30, 1951, p. 33. ↩︎

- Brown Radio Service & Sales advertisement. The Atlanta Journal, October 29, 1952, p. 15. ↩︎

- Advertisement. The Atlanta Constitution, March 14, 1969, p. 14. ↩︎

- National Historic Landmark Nomination: Dixie Coca-Cola Bottling Company Plant ↩︎

- Bailey, Sharon. “GSU Baptist students have hopes to restore 1891 Victorian structure.” The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, December 19, 1982. ↩︎

- Patereau, Alan. “43 Georgia sites are in elite group.” The Atlanta Journal, August 25, 1987, p. 21. ↩︎

- Bailey, Sharon. “GSU Baptist students have hopes to restore 1891 Victorian structure.” The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, December 19, 1982. ↩︎

- Patereau, Alan. “43 Georgia sites are in elite group.” The Atlanta Journal, August 25, 1987, p. 21. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Bailey, Sharon. “GSU Baptist students have hopes to restore 1891 Victorian structure.” The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, December 19, 1982. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Gov. Harris to dedicate new South Fulton chamber building in Union City”. The Atlanta Journal, August 16, 1984, South Fulton Extra, p. 1K. ↩︎

- Bailey, Sharon. “GSU Baptist students have hopes to restore 1891 Victorian structure.” The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, December 19, 1982. ↩︎

- National Historic Landmark Nomination: Dixie Coca-Cola Bottling Company Plant ↩︎

- Fox, Catherine. “Born-Again Buildings”. The Atlanta Journal, December 11, 1989, p. 27. ↩︎

- National Historic Landmark Nomination: Dixie Coca-Cola Bottling Company Plant ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- National Historic Landmark Nomination: Dixie Coca-Cola Bottling Company Plant ↩︎

- Green, Josh. “1890s downtown ATL landmark up for grabs. Any big ideas?“, Urbanize Atlanta. ↩︎

- About Us — BCM at Georgia State ↩︎

- 125 Edgewood – Atlanta – Property for Sale | PL | JLL ↩︎

- Auchmutey, Jim. “Staying the Wrecking Ball”. The Atlanta Journal, August 24, 1988, p. 1D. ↩︎

-

Cummins Corporate Office (1984) – Columbus, Indiana

-

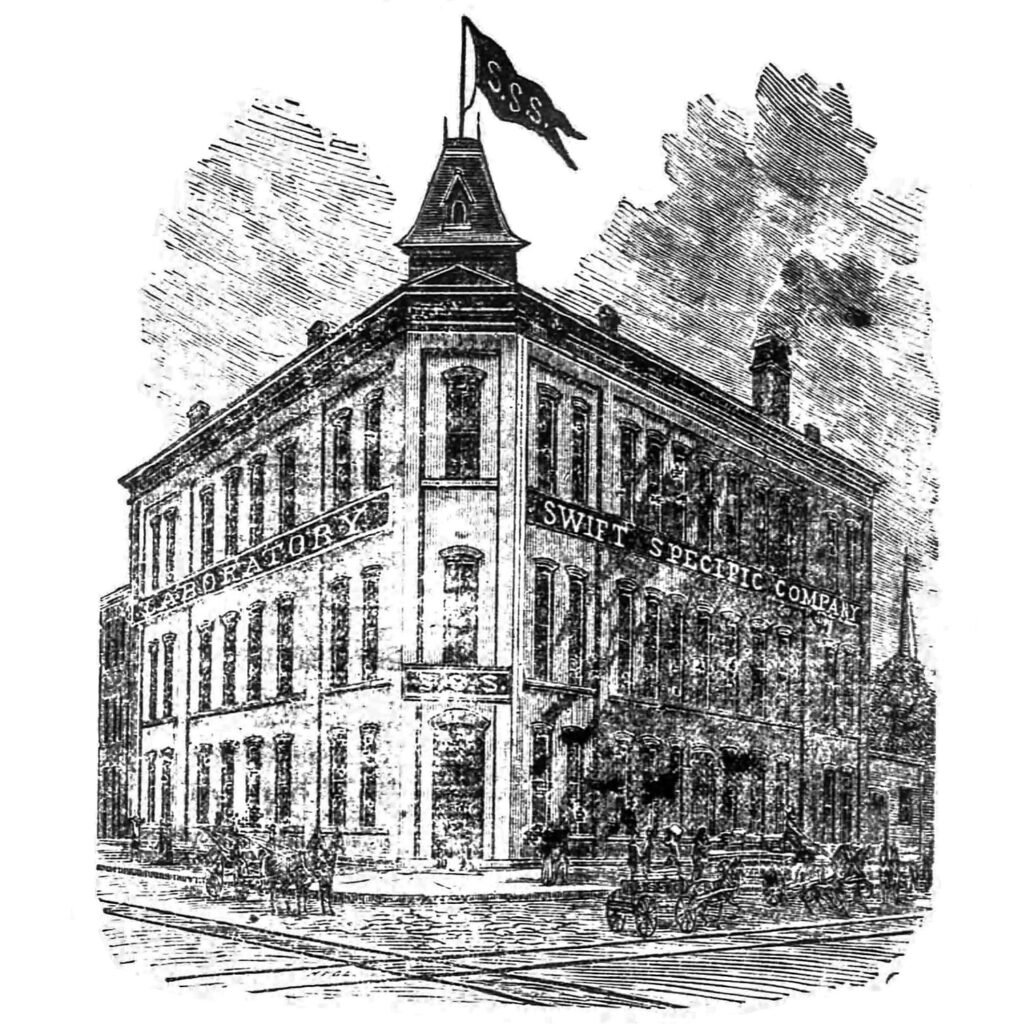

Swift Specific Company – Atlanta (1883-1956)

Edmund G. Lind. Swift Specific Company (1883-1956). Atlanta.1 The Background

The following article was published in The Atlanta Constitution in 1883, and despite its title — “New Atlanta Buildings” — the article discusses a single structure: the laboratory of the Swift Specific Company, designed by E.G. Lind (1829-1909).

Blurring the line between news and advertisement, the article essentially served as a promotion for the Atlanta-based manufacturer of the “S.S.S.” tonic, a cure-all elixir sold across the United States and Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The company still exists, and the product is still manufactured in Atlanta, so I won’t be too disparaging. Suffice it to say, when an unregulated medicinal tonic is billed as the “Great Blood Remedy of the Age,” claiming to cure everything from sores, ulcers, and boils to eczema, rheumatism, blood diseases,2 and — oh, yes — syphilis,3 there’s room to be skeptical.

Typical of Atlanta, the tonic also has a shady and convoluted backstory. The recipe for the remedy was reportedly offered by members of the Muscogee Nation to Irwin Dennard of Perry, Georgia, in 1826. Dennard later sold the formula to Charles T. Swift, who formed a company to manufacture the product, relocating it to Atlanta in 1873.4

Humphries & Norrman were initially reported as the designers of the company’s factory in 1883,5 but all evidence indicates E.G. Lind designed the completed building. Lind’s own project list includes the factory,6 and one of the company’s directors was J.W. Rankin, a repeat client of Lind’s, and a member of the building committee for Atlanta’s Central Presbyterian Church, which Lind also designed.7

Lind’s records indicate that the project cost was $12,000,8 but the company claimed it totaled over $30,000 with machinery.9

Location of Swift Specific Company

The 3-story brick factory was built on the northeast corner of Hunter and South Butler Streets (later Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive SE and Jesse Hill, Jr. Drive SE), bordering the Georgia Railroad.

Then located on the edge of the city, the site was surrounded by a low-rent district of shanties and small factories, but was also two blocks from the central freight depot — ideal for distribution.

In advertisements from the 1880s and 1890s, the company often touted its proximity to the Georgia State Capitol, located one block west of the factory. The Fulton County Jail was later built next door to the facility, but they never mentioned that in their marketing.

Considering the company’s constant promotion in the Atlanta press, it’s surprisingly difficult to find any articles that discuss the development of its property after 1883.

At some point between 1899 and 1911, the factory appears to have doubled in size.10 11 My best guess is that the expansion took place circa 1902, after the company bought an adjoining lot on Hunter Street in 1901.12 Who the designer of the addition was is unclear — Lind left Atlanta in 1893 and retired from practice.

Later renamed the S.S.S. Company, the factory continued operating at the same location until circa 1956-57, when the entire area was acquired and cleared for the construction of the I-75/85 Downtown Connector.13 14 The site is now occupied by an exit ramp.

“New Buildings In Atlanta.”

New Laboratory Of The Swift Specific Co.

Now being erected corner Hunter and Butler streets, one block below the City Hall, one hundred feet long, eighty feet

wide–three stories and cellar.We give a drawing of the new Laboratory of The Swift Specific Company now being built corner Hunter and Butler streets. This will be a handsome building, an ornament to that part of the city, and is not only an evidence of the thrift and growth of Atlanta, but is a most substantial proof the confidence of the proprietors of this extraordinary remedy in its merit, and the permanent business of its manufacture and sale. In fact, they know so well that their remedy is all they claim for it, they have no hesitation in investing twenty to forty thousand dollars in substantial buildings and improved machinery for its manufacture. They will have in their new Laboratory at [sic] 30-horse power engine, two boilers, ten immense steam tight percolators, a large mill for grinding the roots, a powerful press of two tons to the inch for extracting the juices, besides numerous bottle washing and bottle filling machines. Taken as a whole, it will be, when finished, one of the most complete Laboratories in America, and will be superintended by a practical Pharmacist and Chemist of 25 years experience.

Since Swift’s Specific has come into general use as a health tonic, the demand has increased so rapidly and largely that the Company have had difficulty in keeping up the supply, but now they expect to be prepared for all emergencies, as their capacity will be, after October 1st, over a million dollars a year.

Letters From the People.

A Marvelous Cure.

From the Memphis Appeal, August 1.

To the Editors of the Appeal: Noticing in your paper where S.S.S. had effected a cure in an aggravated case of scrofula, I have concluded to give My experience with the remedy mentioned. Some time ago I was afflicted with a very stubborn case of eczema; at the time I was living in Philadelphia. It got worse and worse, until my face and other portions of my body were covered with a mass of running sores. I visited my family physician, and after being under his care for a long time without any relief he turned me over to Prof. Duffing, a noted expert on skin diseases, and after swallowing a barrel of medicine prescribed by him without giving me any relief, I consulted with several other professional experts with a like success. I was miserable, and despaired of a cure. Being very skeptical in regard to the effect of patent medicines, I had as yet not tried any, but being advised by many people I commenced at the top of the list of patient remedies for eczema, ectyma, mentagra and other skin affectations, and I think I tried them all, still however, without doing me any good. I had heard of S.S.S., and although I had been repeatedly advised by my friends to try it, still as each remedy failed in producing the desired result, and as with each failure my skepticism increased, I refused to take it until in utter desperation I concluded to give it a trial as a last resort, not believing, however, it would have a beneficial effect. But to my surprise, after taking several bottles, I noticed a decided improvement, and when I had finished the fifth bottle I shouted hurrah, for my skin was without a blemish, as fair and smooth as possible. I write this in the interest of anyone that may be afflicted likewise, and now I swear by S.S.S.

DRUMMER.

P.S.–I would be pleased to correspond with anyone that is interested, and give them full details.Address “DRUMMER,”

Care Memphis Appeal15References

- Photo credit: Atlanta in 1890: “The Gate City”. Atlanta: The Atlanta Historical Society, Inc. (1986), p. 35. ↩︎

- “Swift’s Specific” (advertisement). The Atlanta Constitution, February 18, 1883, p. 10. ↩︎

- “Important Reduction In Price Of Swift’s S. Specific” (advertisement). The Atlanta Constitution, October 23, 1891, p. 6. ↩︎

- Company Leadership Over the Years – S.S.S. Company ↩︎

- “How We Grow.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 10, 1883, p. 3. ↩︎

- Belfoure, Charles. Edmund G. Lind: Anglo-American Architect of Baltimore and the South. Baltimore, Maryland: The Baltimore Architectural Foundation (2009), p. 180. ↩︎

- Belfoure, p. 144. ↩︎

- Belfoure, p. 180. ↩︎

- Company advertisement. The Atlanta Constitution, December 16, 1883, p. 4. ↩︎

- Insurance maps of Atlanta, Georgia, 1899 / published by the Sanborn-Perris Map Co. Limited ↩︎

- Insurance maps, Atlanta, Georgia, 1911 / published by the Sanborn Map Company ↩︎

- “Property Transfers.” The Atlanta Journal, September 9, 1901, p. 5. ↩︎

- Hamilton, Joe. “Big Change Coming In Street Network”. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, June 10, 1956, p. 1-C. ↩︎

- “Work Begins on Connector Link Sewer Project”. The Atlanta Journal, January 10, 1957, p. 25. ↩︎

- “New Buildings In Atlanta.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 5, 1883, p. 11. ↩︎

-

First Federal Savings and Loan Building (1964) – Atlanta

-

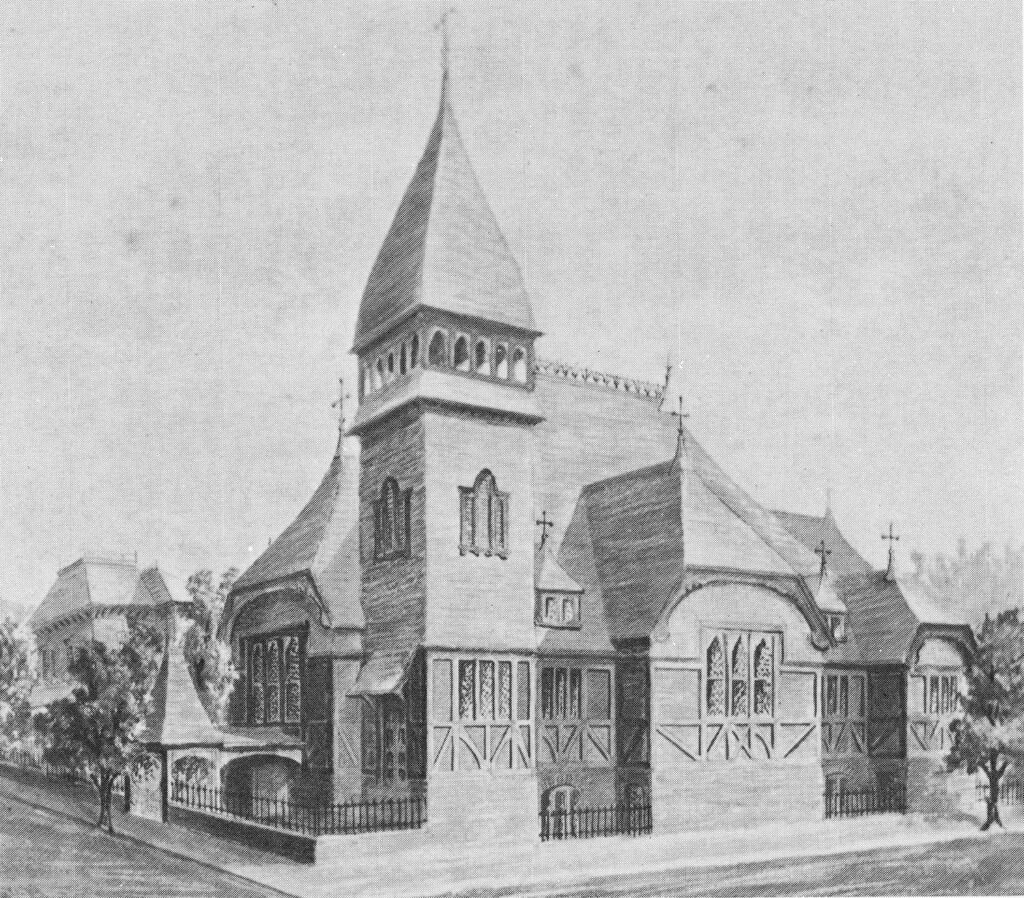

“St. Luke’s Cathedral” (1883-1906)

G.L. Norrman. St. Luke’s Cathedral (1883-1906). Atlanta.1 The Background

The following article was published in The Atlanta Constitution in February 1883, and celebrated the completion of one of the first major works by G.L. Norrman (1848-1909) in Atlanta: St. Luke’s Cathedral.

Although the project was credited to the firm of Humphries & Norrman, it appears Norrman was the primary designer — the illustration included with the article is even signed in his handwriting.

St. Luke’s Episcopal Church was founded in 1864, with its first building destroyed by the Union army in the burning of Atlanta.2 The church’s second structure was located at the southeast corner of Spring and Walton Streets,3 but in 1882, the congregation was forced to sell the property after it failed to pay for furnishings from a local store owner, who in turn sued the church and won.4 Pay for your pews, damn it.

Humphries & Norrman began working on plans for a new building in July 1882, although it wasn’t clear if the project would even be executed, as the church also considered moving its old structure to their new property5 at the northeast corner of Houston and Pryor Streets, just off Peachtree Street.

Location of St. Luke’s Cathedral

The plans were ultimately accepted, and construction on the sanctuary was rapid — about 4 months. Building had “begun only a few weeks ago” when the cornerstone was laid on October 21, 1882,6 and the first service was held in the church’s basement on Christmas Day 1882,7 although the interiors were completed in February 1883.

The article below describes the building’s interior in exacting detail, but doesn’t say anything about its exterior, which was clad in brick and topped with a 60-foot-high steeple.8 The final cost of the project was just $5,500.9

When the church was constructed, it was barely within the city limits and towered over the one and two-story homes around it.

Within ten years, Atlanta’s ever-expanding commercial district engulfed the building, and in 1892, when the church lost its cathedral designation to nearby St. Philip’s,10 the St. Luke’s sanctuary was overshadowed by the rise of its new next-door neighbor: DeGive’s Grand Opera House, a 7-story entertainment palace.

One year later, Atlanta’s first “flatiron” structure, the 3-story commercial Peck Building, designed by G.L. Norrman, was erected on a sliver of land across from St. Luke’s entrance, blocking the church’s exposure to Peachtree Street.

In 1906, only twenty-three years after the sanctuary’s completion, St. Luke’s sold out to DeGive,11 and the congregation moved further up Peachtree Street into a new building designed by P. Thornton Marye,12 13 which still stands.

Georgia-Pacific Center (1982), the former site of St. Luke’s Cathedral. Atlanta. The old St. Luke’s was demolished in October 1906, with materials from the structure salvaged to build a home on Gilmer Street,14 also long since destroyed. The former church property was replaced with a block of single-level stores15 and is now the site of the Georgia-Pacific Center in Downtown Atlanta.

After the sanctuary was demolished, “M.S” commented on the church’s move in the “Women and Society” column of The Atlanta Journal:

In olden times if a congregation wished to build a new church and leave the old building for the new it was looked upon by other congregations with distress and disapproval, and the next thing to giving up their religion itself. This no doubt was only sentiment; but it seems to me if we of this day would cultivate a little more of the true sentiment and love for the pure and beautiful and less of the worldlier sentimental we would live sweeter and more wholesome lives, nearer in a true sense to one another, to nature and to nature’s God.16

Bitch, please, this is Atlanta.

St. Luke’s Cathedral.

Was yesterday finished and will be opened to-day to the public, and is one of the handsomest churches in the city.

It is located on the corner of Houston and Pryor street, facing Peachtree. The plans were drawn by Messrs. Humphreys and Norman [sic], architects. Under their personal supervision it has been built and they have reason to feel proud of it. The contractors, Messrs. Oliver and Carey, and their foreman, Mr. Edward Edge, deserve much credit for the construction. It is of the old English architecture and is much admired. The interior finish in ceiling is Georgia pine left in its natural color, all other woodwork walnut, except the pews which are ash ends and poplar seats and backs, all upright walls are plastered and will be frescoed by Messrs. Sheriden & Bro.

The chancel furniture is being made the Gate City Planing company and will be finished within two weeks and will consist of the bishop’s chair with canopy, altar table with eight foot arch, credance table, two priest’s chairs, two priest’s stalls and kneeling desks, pulpit, two lectern, all walnut except the credence tables, which is made of Virginia pine from the old Blankford church, near Petersburg, Virginia, built in colonial days over one hundred fifty years ago.

The chancel will be enclosed with a brass rail now being made in New York.

The church will be lighted with gas, having one large 20 light chandelier and 12 two light brackets. The organ will be a very fine one and built by Messrs. Pilcher & Co., of Louisville, Ky. Negotiations are now progressing for its constrnction [sic]. The font will be of Tennessee marble and be located at the intersection of the aisles in the body of the church.

A cathedral is the principal church in a diocese and is where the bishop presides and has a seat is the center of his authority.

Atlanta is the residence of the bishop of Georgia and St. Luke’s has been built for the bishop as the cathedral

Space forbids a more detailed description of the new church. The following sessions will be held therein commencing this morning at seven o’clock and continue during Lent:

The Rev. Mr. Beckwith will preach to-day at 11 o’clock, and the Rev. Mr. Williams this evening at 7:30 o’clock.17

References

- Illustration credit: Lyon, Elizabeth A. Atlanta Architecture: The Victorian Heritage, 1837-1918. The Atlanta Historical Society (1976), p. 43. ↩︎

- “St. Luke’s Church Now For Sale By Owner”. The Atlanta Journal, July 29, 1906, p. 12. ↩︎

- “Auction Sale of Central Property.” The Atlanta Constitution, August 6, 1882, p. 3. ↩︎

- “A Verdict Against a Church.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 22, 1882, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Real Estate and Industrial Notes.” The Atlanta Constitution, July 28, 1882, p. 7. ↩︎

- “The Corner-Stone”. The Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 1882, p. 6. ↩︎

- “St. Luke Episcopal Church To Build At Once”. The Atlanta Journal, March 9, 1906, p. 7. ↩︎

- Atlanta, Georgia, 1886 / published by the Sanborn Map and Publishing Co Limited ↩︎

- “The Building Outlook.” The Atlanta Constitution, February 1, 1883, p. 7. ↩︎

- “St. Luke Episcopal Church To Build At Once”. The Atlanta Journal, March 9, 1906, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Big Apartment House On St. Luke’s Site”. The Atlanta Journal, August 1, 1906, p. 15. ↩︎

- “Plans Of New St. Luke Church Completed By Architect Marye”. The Atlanta Constitution, January 12, 1906, p. 3. ↩︎

- “St. Luke Episcopal Church To Build At Once”. The Atlanta Journal, March 9, 1906, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Tearing Down Old Landmark”. The Atlanta Constitution, October 12, 1906, p. 11. ↩︎

- Insurance maps, Atlanta, Georgia, 1911 / published by the Sanborn Map Company ↩︎

- M.S. “The Passing of Old St. Luke’”. The Atlanta Journal, November 11, 1906, p. 6S. ↩︎

- “St. Luke’s Cathedral”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 11, 1883, p. 9. ↩︎

-

“Atlanta Women Win Success in Business” (1913)

Henrietta C. Dozier. W.A. Turner Residence (1913). Newnan, Georgia. The Background

The following excerpt is from an article published in The Atlanta Journal in 1913, featuring an interview with Henrietta C. Dozier (1872-1947), the first female architect in Atlanta and the Southeastern United States.

What a difference 12 years makes. Compared to the first profile of Dozier in 1901, this article about Atlanta businesswomen is downright respectful — the male reporter even puts “weaker” in quotations when mentioning the ‘”weaker” sex.’ Progress!

Women’s suffrage was still 7 years away, but as the article notes, Atlanta women were increasingly making inroads into male-dominated professions, including photography, real estate, medicine, dentistry, and, of course, architecture.

“… it is only a question of time when there will be no typically masculine projects,” the writer opines.

As always, Dozier was characteristically forthright about the difficulties of her profession (“It is a hard life…”) and didn’t hesitate to recognize her role as a pioneer for other women — “It was left for me to open a pathway where other women shall reap success.”

This article is one of just a few that list some of Dozier’s notable projects during her time in Atlanta, making it a particularly valuable research source.

Article Excerpt:

“The old bubble that the north is a better field of business for a woman than the south has been decidedly polted.”

So speaks the woman architect of Atlanta. Another one backs her up, a woman photographer joins her voice in the assertion, a female real estate agent drives it into one ear and tries to sell you a lot through the other, a half a dozen doctors and dentists of the “weaker” sex agree with them.

They do not have to put it into words. It can be seen with half an eye. It is visible in the crowded ante-rooms of the women doctors, in the beautiful pictures in the photographer’s windows, in the scores of blue prints overflowing the architect’s table.

When a woman succeeds in a woman’s work it is not surprising. When a man succeeds in a woman’s work the world is not astonished. But the woman winning success in a business which is properly a man’s, is another matter.

It will not be long, however, before it will be impossible for women to gain distinction in a masculine project, for it is only a question of time when there will be no typically masculine projects. The women are making them their own.

SOUTHERN BUSINESS WOMEN.

In the north and east, even in the west, women have been breaking into business for the last quarter of a century. In the south, in Atlanta, a real business woman is still enough of a rarity to win the public gaze and incidentally the public patronage.

Business women who have tried their hand in Atlanta have tried their hand in the north as well, will tell you that there is no place like the south. Their slogan is an adaptation of Horace Greely‘s “Young girls, come south”.

There is Miss Henrietta Dozier, the woman architect who has had all the business she could handle for the last eleven years. She has had offices in the Peters building for eleven years, she has been in the south but eleven years, she has been successful eleven years.

Not that Miss Dozier is advising any girl to go to work.

“It is a hard life,” she says, “and if I had a daughter, I wouldn’t want her to do architectural or any other kind of work.”

Atlanta should feel proud of Miss Dozier. She is a graduate of the Girls’ High school and has made her name one of the foremost in American architectural circles.

Dozier graduated from Boston Tech, a full-fledged architect. She had accomplished the dream of her girlhood, fulfilled the ambition which was born in her when she used to build houses of A B C blocks and which clung to her all through her High school days.

First, she tried architecture in Boston, and the result is the very reason she likes Atlanta better. South she came, was in Jacksonville for eighteen months, and then reached Atlanta, where she was in the office of Walter T. Downing for another eighteen months.

PIONEER FOR WOMEN.

Eleven years ago she went into business for herself. At the time there was not another woman practicing architecture south of Mason and Dixon’s line. Miss Dozier was the pioneer who blazed the way.

“It was left for me to open a pathway where other women shall reap success,” said Miss Dozier.

Her own success has been far-reaching. Among the best work she has done is on the Nelson Hall school for girls, soon to be erected on Peachtree road; a shooting box for Mrs. Ernest Lorillard in Buford, S.C.; the Southern Ruralist building in Atlanta, an office building at Buchanan [sic], W. Va.; churches in Jacksonville, Fitzgerald, Gainesville, Barnesville; and numerous residences, among them Mr. Blackmar‘s in Columbus, Ga., Bishop Nelson‘s and Arnold Broyles‘ in Atlanta, Dr. W.A. Turner‘s in Newnan.1

References

- Greene, Ward S. “Atlanta Women Win Success In Business”. The Atlanta Journal, June 15, 1913, Women’s Section, p. 3. ↩︎

-

Walton Jackson Building – Gainesville, Georgia (1936)

Walton Jackson Building (1936). Gainesville, Georgia.1 We’ll go with 1936 as the date for this fine building in Gainesville, Georgia, designed in the Classic Moderne style and elegantly clad in marble.

I suspect the structure was designed by Daniel & Beutell of Atlanta, who profited handsomely after Gainesville’s commercial district was substantially destroyed by a tornado in April 1936.2 3

Daniel & Beutell designed the nearby Hall County Courthouse and Gainesville City Hall — both are similar in style and appearance to this building. The firm also designed another project for Walton Jackson in 1936.4

- “Gainesville Lot Sold For $37,500”. The Atlanta Journal, April 29, 1936, p. 14. ↩︎

- “43 Known Dead, Others Feared Lost In Debris, Hundreds Are Injured In Gainesville Tornado”. The Atlanta Journal, April 6, 1936, p. 1. ↩︎

- “150 Are Known Dead At Gainesville; Fires Ravaging City Are Controlled”. The Atlanta Constitution, April 7, 1936, p. 1. ↩︎

- Manufacturer’s Record Daily Construction Bulletin, Volume 77 (1936). ↩︎