Category: Architecture

-

FMC Tower (2016) – Philadelphia

Pelli Clarke & Partners with BLT Architects. FMC Tower (2016). Philadelphia.1 -

Prayer for the New Year

Pickard Chilton with HKS. Norfolk Southern Headquarters (2022). Atlanta.1 May the darkness of fear and illusion dissipate;

May the light of grace and truth shine through.

References

-

W.W. Goodrich on Henry W. Grady (1891)

Alexander Doyle. Henry. W. Grady Monument (1891). Atlanta. The Background

Henry W. Grady (1850-1889) was the editor of The Atlanta Constitution in the 1880s, as well as the originator and chief proselytizer of “The New South” mythology that Atlanta still clings to as gospel.

If anyone in post-Civil War America was unaware of Grady’s conception of the New South, he considered it his life’s mission to indoctrinate them, criss-crossing the United States and preaching his message of a resurgent South in a series of public speeches.

Grady’s big idea was to decrease the Southeast’s economic reliance on agriculture and attract industry to the region with cheap labor, envisioning Atlanta as its epicenter.

The city and mythology soon became synonymous, and Atlanta developed a reputation as a progressive, “wide-awake” metropolis in a region that had long been viewed as backward and rural.

The vision of the New South was anything but progressive, however, and Grady was simply regurgitating the stale promises of capitalism with a Southern twang.

He was also an avowed white supremacist who lamented the region’s “Negro problem,” which is to say, that Black people existed at all. Among some of Grady’s choice remarks on the subject is this subtle proclamation:

But the supremacy of the white race of the South must be maintained forever, and the domination of the negro race resisted at all points and at all hazards, because the white race is the superior race.1

In other words, the New South was to be built on the same old bullshit as the Old South.

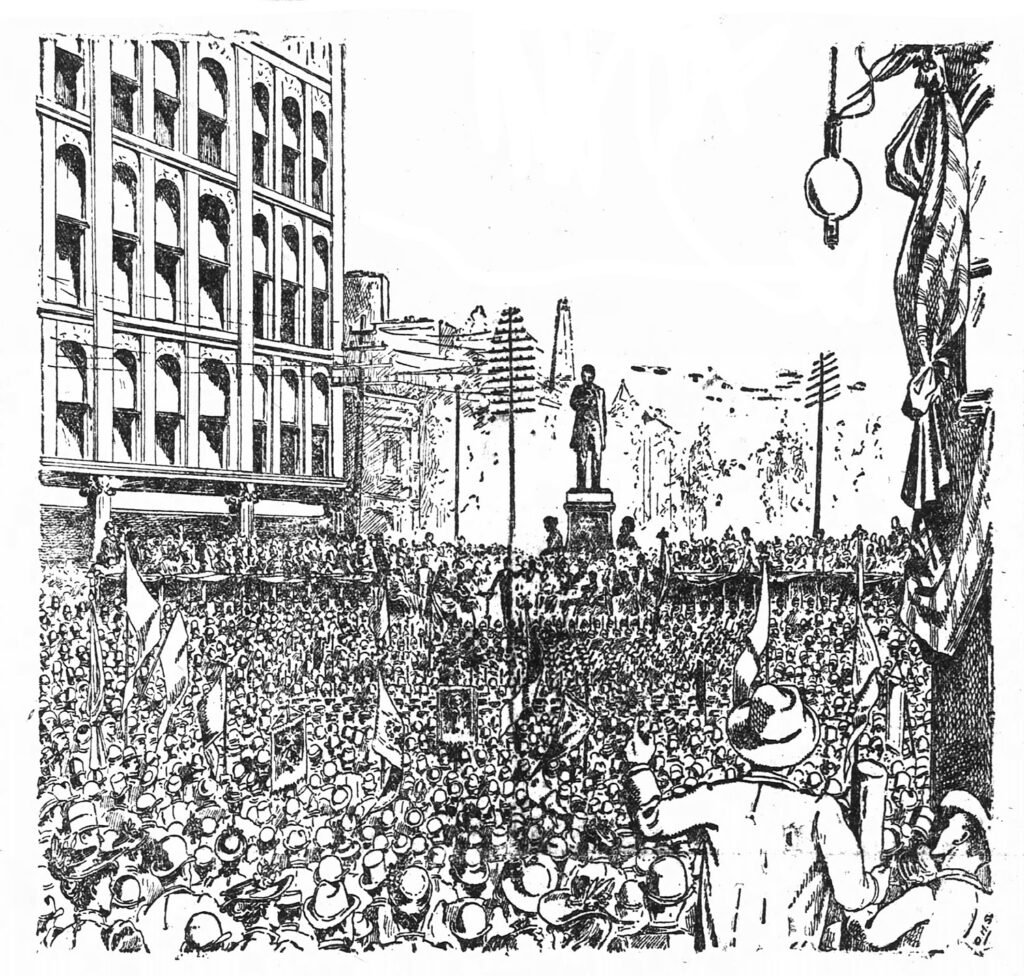

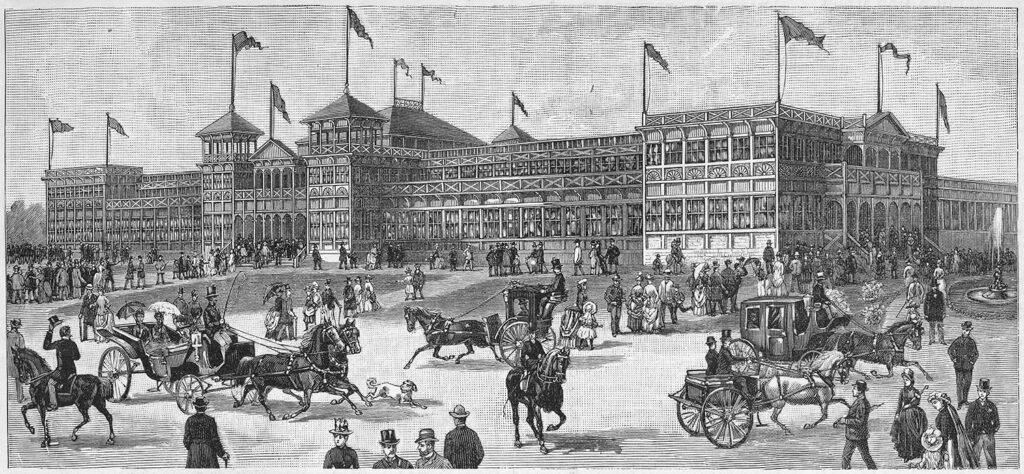

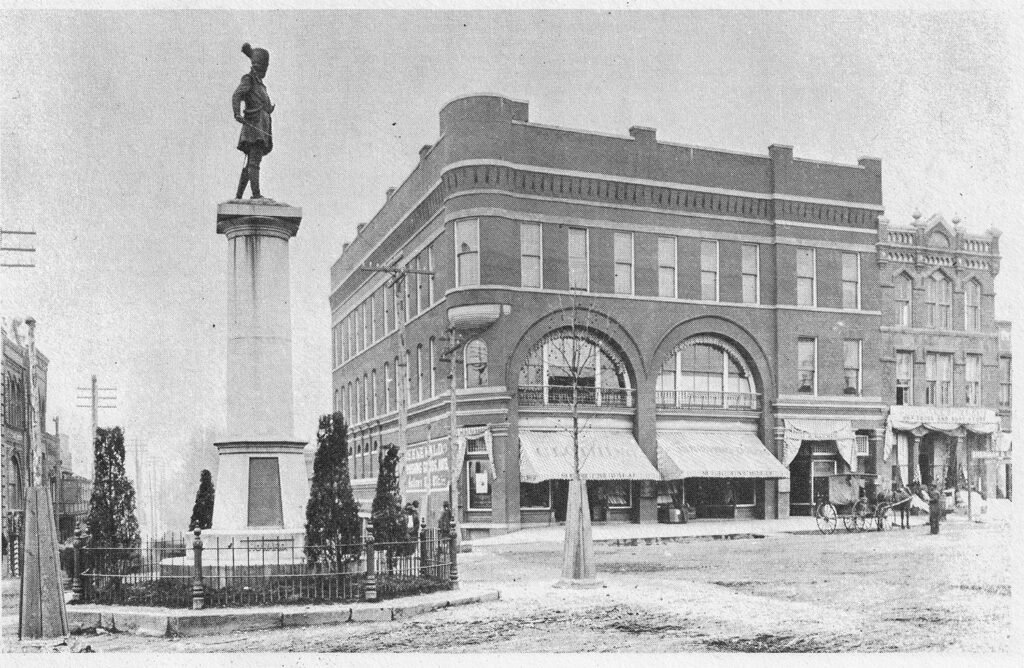

Illustration of the unveiling of the Henry W. Grady Monument, October 21, 18912 Americans love to deify racist orators, and when Grady suddenly died in December 1889, he was immediately beatified by white Atlantans as some patron saint of the city. A movement quickly grew to erect a monument to him, and in March 1890, a local committee accepted the design for a bronze statue sculpted by Alexander Doyle.3

The Henry Grady monument was unveiled in a lavish public ceremony on October 21, 1891,4 which the Constitution predictably covered as if it were the event of the century, claiming that crowds in attendance ranged from 25,000 to 50,000 people,5 no doubt greatly exaggerated since the city’s population was less than 70,000 at the time.6

A monument to Grady wasn’t enough, however, and for decades the city slapped his name on various streets and buildings, including Grady Memorial Hospital and Grady High School in Midtown. The high school finally dropped his name in 2021,7 but the hospital remains “Grady”, and it’s hard to imagine a world in which Atlantans would ever call it anything else.

The Grady monument was erected at the intersection of Marietta and Forsyth Streets, and during the 1906 Atlanta race massacre, it served as an altar for the bodies of three Black men murdered by an angry white mob.

As the Constitution told the story:

One of the worst battles of the night was that which took place around the postoffice. Here the mob, yelling for blood, rushed upon a negro barber shop just across from the federal building.

“Get ’em. Get ’em all.” With this for their slogan, the crowd, armed with heavy clubs, canes, revolvers, several rifles, stones and weapons of every description, made a rush upon the negro barber shop. Those in the first line of the crowd made known their coming by throwing bricks and stones that went crashing through the windows and glass doors.

Hard upon these missiles rushed such a sea of angry men and boys as swept everything before them.

The two negro barbers working at their chairs made no effort to meet the mob. One man held up both his hands. A brick caught him in the face, and at the same time shots were fired. Both men fell to the floor. Still unsatisfied, the mob rushed into the barber shop, leaving the place a mass of ruins.

The bodies of both barbers were first kicked and then dragged from the place. Grabbing at their clothing, this was soon torn from them, many of the crowd taking these rags of shirts and clothing home as souvenirs or waving them above their heads to invite to further riot.

When dragged into the street, the faces of both barbers were terribly mutilated, while the floor of the shop was met with puddles of blood. On and on these bodies were dragged across the street to where the new building of the electric and gas company stands. In the alleyway leading by the side of this building the bodies were thrown together and left there.

At about this time another portion of the mob busied itself with one negro caught upon the streets. He was summarily treated. Felled with a single blow, shots were fired at the body until the crowd for its own safety called for a halt on this method, and yelled “Beat ’em up. Beat ’em up. You’ll kill good white men by shooting.”

By way of reply, the mob began beating the body of the negro, which was already far beyond any possibility of struggle or pain. Satisfied that the negro was dead, his body was thrown by the side of the two negro barbers and left there, the pile of three making a ghastly monument to the work of the night, and almost within the shadow of the monument of Henry W. Grady.

So much for the city too busy to hate.

The Grady statue still stands at the intersection of Marietta and Forsyth Streets in Downtown Atlanta, but it’s easy to overlook. In June 1996, it was moved 10 feet from its original spot for greater visibility,8 but it remains surrounded on both sides by a canyon of glass and steel buildings that casts the monument in near-constant shadow — that’s probably for the best.

When the statue was unveiled in 1891, W.W. Goodrich felt the need to offer his thoughts on the subject — because of course he did — with remarks to the Constitution that should be viewed with great skepticism, given his well-noted propensity for lying.

In the following article excerpt, Goodrich claims to have had “several conversations” with Grady — “in his sanctum,” no less –and acts as if the two men were intimate friends.

Let’s do some quick math here: Goodrich came to Atlanta in September 1889,9 and Grady died on December 23, 1889, after a month-long bout of pneumonia, during which time he also took extended trips to New York and Boston.10

Would a no-name newcomer from California have been able to engage in “several conversations” with Grady in under 3 months? I have serious doubts.

Here, Goodrich also compares Grady to Abraham Lincoln, with whom he was apparently quite enamored [see also: “The President and the Bootblack“], sharing an apocryphal tale about Lincoln that he undoubtedly pulled straight from his ass.

And on that note, we won’t be hearing much more of Goodrich’s bullshit for a while. Thank God.

Article Excerpt:

All during the day, and away into every night, there is a group around the Grady statue. Yesterday it was surrounded all day by men, women and children, who were studying the bronze figure. As late as 10 o’clock last night there were at least twenty people in front of the statue, gazing at it.

Mr. W.W. Goodrich, the architect, says:

Looking upon that face in living bronze, studying its points of character, the many thoughts of the several conversations I had with him pass in review before my memory. Shortly after making Atlanta my home, I called upon Mr. Grady in his sanctum. Always courteous, cordial, and painstaking in a marked degree, to make a stranger at home, in his beloved city, was he to every one. He never referred to the past, but that he predicted from out of it would arise in the south, in this favored region, the grandest lives of our future republic. He predicted that the mighty forces of science would hereabout establish those appliances of labor that would elevate the new south above her most rosy anticipations.

“And why not,” said Mr. Grady to me once, “about us all are the minerals, inexhaustible, that are used in manufacturing enterprises. Our fields give us the raw material for our spindles to manipulate, our firesides are aglow with fuel from nearabout, our food products can all be raised here, our climate cannot be excelled, our transportation facilities place us speedily in all the markets of the world. Again, the active hands behind all this are young men who were boys after the surrender. From bank presidents down to humble vocations, our young men are the leading spirits.”

And whilst I listened to the speeches of Mr. Clark Howell and his co-laborers, at the unveiling ceremonies last Wednesday, I could not help but think of Mr. Grady’s remarks: “Our young men are back of it all, and are the active hands in the forwarding of all this remarkable prosperity and progress.”

Atlanta is peculiarly a city of young men. Their influence is felt on every hand, in every vocation, trade or profession. The brainy young men are back of it all, of all this wonderful and real prosperity, of all this great progress, and the future greatness of our city can be ascribed to the young men. And Mr. Grady was a young man. His addresses show the fire of youth with the mannered culture of experience. The young men of the new south are her bone and sinew, the coming giants in the political arena. The star of empire, for solid practical government, that government of the people, for the people, and by the people, that government of genuine Americans for Americans, is here in the south. From my observation, I verily believe there is more Americanism in the south than in all the rest of the country put together; and more love of American institutions for what they have been, for what they are and for what they will be in the future.

Mr. Grady admired the character of Lincoln, and with emotion remarked that the south lost her best friend when Mr. Lincoln died. He stated that Washington and Lincoln were the two greatest men of the world. And Governor Hill, in his remarkable eulogy of Mr. Grady, at the unveiling ceremonies, likened Washington, Lincoln and Grady as the three greatest men of our country.

Having occasion to visit Philadelphia during the early part of the war, Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward were in a car with several distinguished confederate soldiers on parole. These gentlemen were personally known to Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward, and as they chatted together in a most cordial manner, one of the confederate officers said: “Mr. President, what think you of the war?” Grasping the subject instantly, Mr. Lincoln asked:

“General, what do you think of the old flag?” The general’s color instantly turned and he did, not answer. Rising from his seat across the aisle he paced up the car and back to Mr. Lincoln’s seat and finally replied: “Right there was the south’s mistake.” “Yes,” said Mr. Lincoln, “had the south come north with the old flag, there would have been no war.”

I asked Mr. Grady is he had ever heard of the above conversation. He said that he had from one of the generals who was with Mr. Lincoln at that time. He stated the general’s name, and this same general was a very prominent man in the confederacy, and also stated that Mr. Lincoln’s remark about the old flag, was the truth.

Referring to this conversation, at a subsequent interview, Mr. Grady said: “There as one distinct thought that occurs to me, and that is this, Mr. Lincoln was peculiarly a man of the masses, and not of the classes.” Mr. Grady was a man of the masses, and not of the classes, and therein he was like Mr. Lincoln. His strong position with the masses made his paper, The Constitution, to be read by untold thousands all over the country, who saw in the new south that future of prosperity and progress that was typical in Mr. Grady’s greatness of heart, and of which he was the prime mover and its unflinching champion.11

References

- Life and Labors of Henry W. Grady. Atlanta: H.C. Hudgins & Co. (1890), p. 186. ↩︎

- The Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 1891, p. 1. ↩︎

- “The Grady Monument”. The Atlanta Constitution, March 6, 1890, p. 3. ↩︎

- “In Living Bronze.” The Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 1891, pp. 1-2. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- Biggest Cities in Georgia – 1890 Census Data ↩︎

- Midtown High School (Atlanta) – Wikipedia ↩︎

- “Grady Moved By Olympics”. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 14, 1996, p. E1. ↩︎

- “Comes Here to Live.” The Atlanta Constitution, September 18, 1889, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Henry Grady Dead!” The Atlanta Constitution, December 23, 1889, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Etched And Sketched.” The Atlanta Constitution, October 26, 1891, p. 4. ↩︎

-

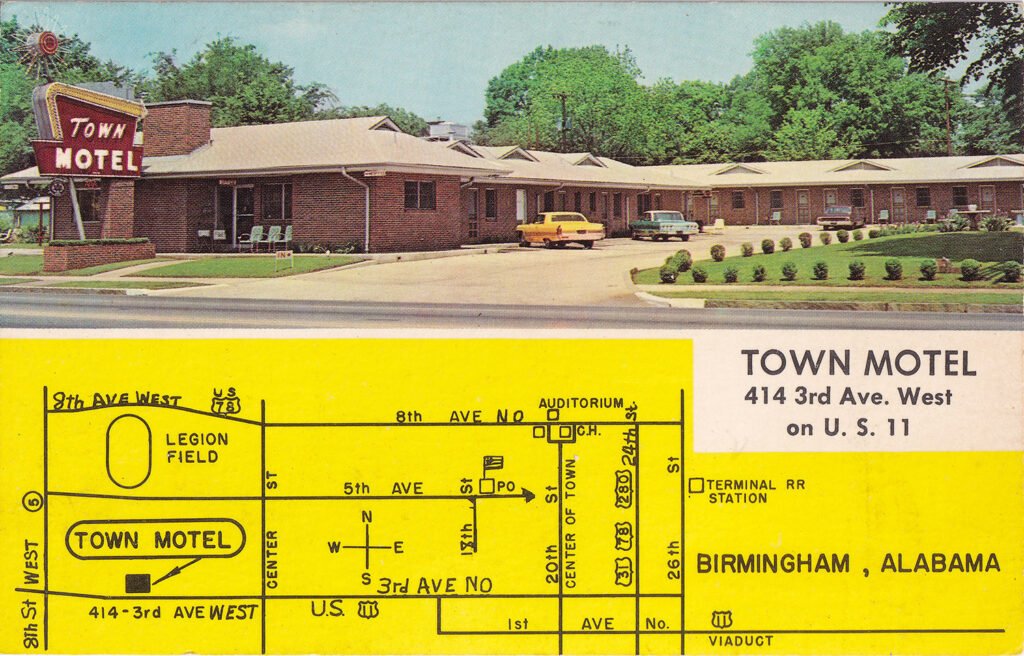

Relic Signs: Town Motel – Birmingham, Alabama

Town Motel (sign debuted after 1957). 414 3rd Avenue West, Birmingham, Alabama. It’s hard to nail down a precise date for this fantastic Googie-style sign, but it was likely erected sometime after 1957.

The Town Motel opened in 19511 and expanded in 1957,2 but newspaper images from both dates show two completely different signs — neither of them was this one.

An undated postcard, pictured below, shows the sign in its original — and much more pristine — condition, noting that the motel was owned and managed by Mr. and Mrs. Charles D. Mitchell and Son, who operated the establishment from 1951 to at least 1960.3

References

- “Phone Seale Lumber For Loan Information.” Birmingham Post-Herald (Birmingham, Alabama), May 26, 1951, p. 8. ↩︎

- “Town Motel Again Re-orders From Rhodes-Carroll”. The Birmingham News (Birmingham, Alabama), February 23, 1957, p. 14. ↩︎

- Polk’s Birmingham (Jefferson County, Alabama) City Directory 1960. Richmond, Virginia: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers (1960). ↩︎

-

Fourth Ward (2023) – Atlanta

Olson Kundig Architects. Fourth Ward (2023). Old Fourth Ward, Atlanta. 1 References

-

“Incongruities of Modern Architecture” (1893) by W.W. Goodrich

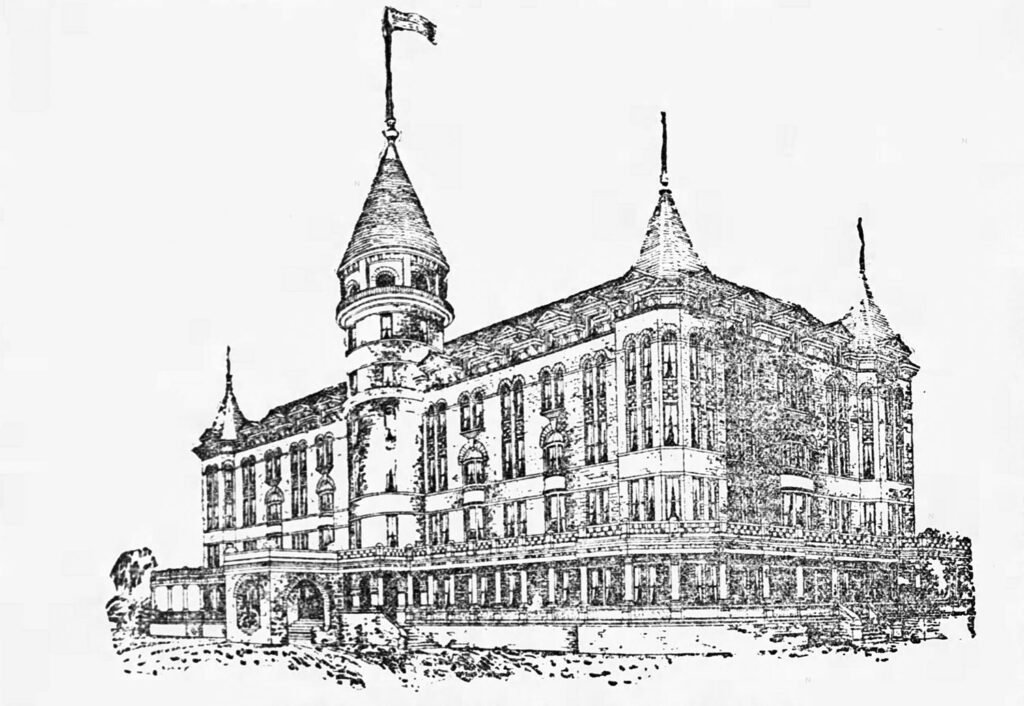

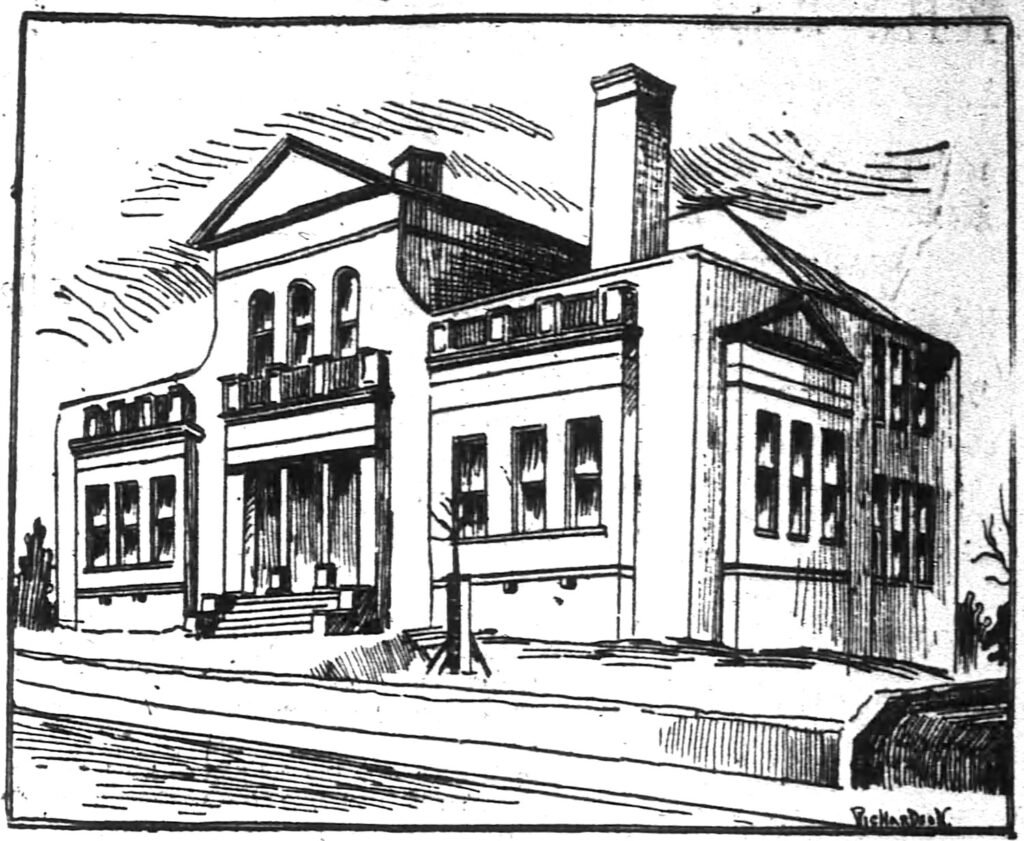

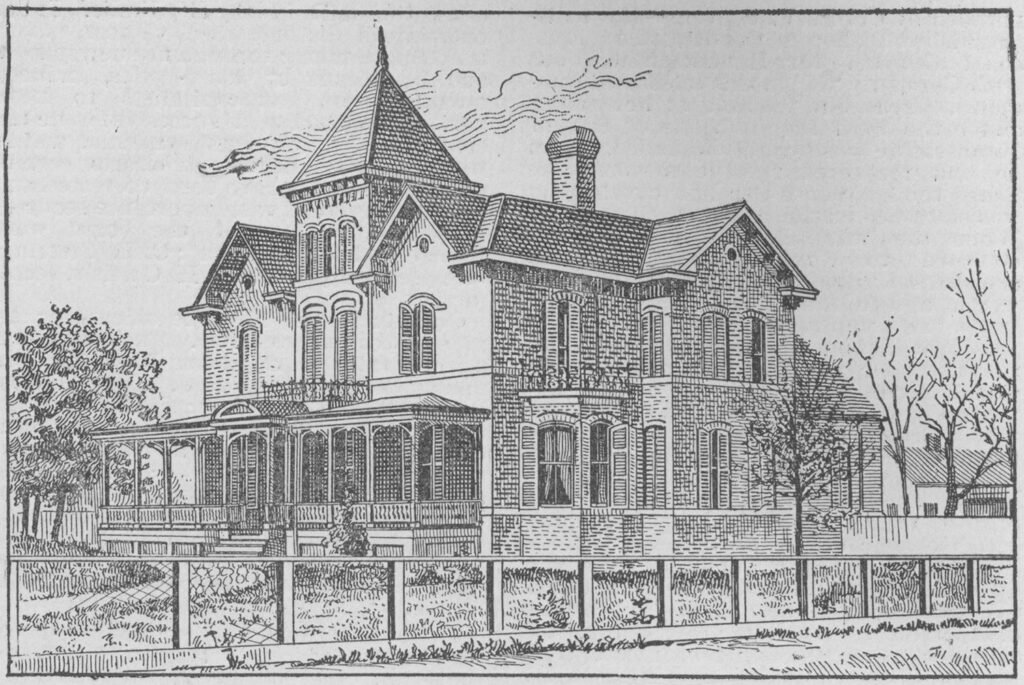

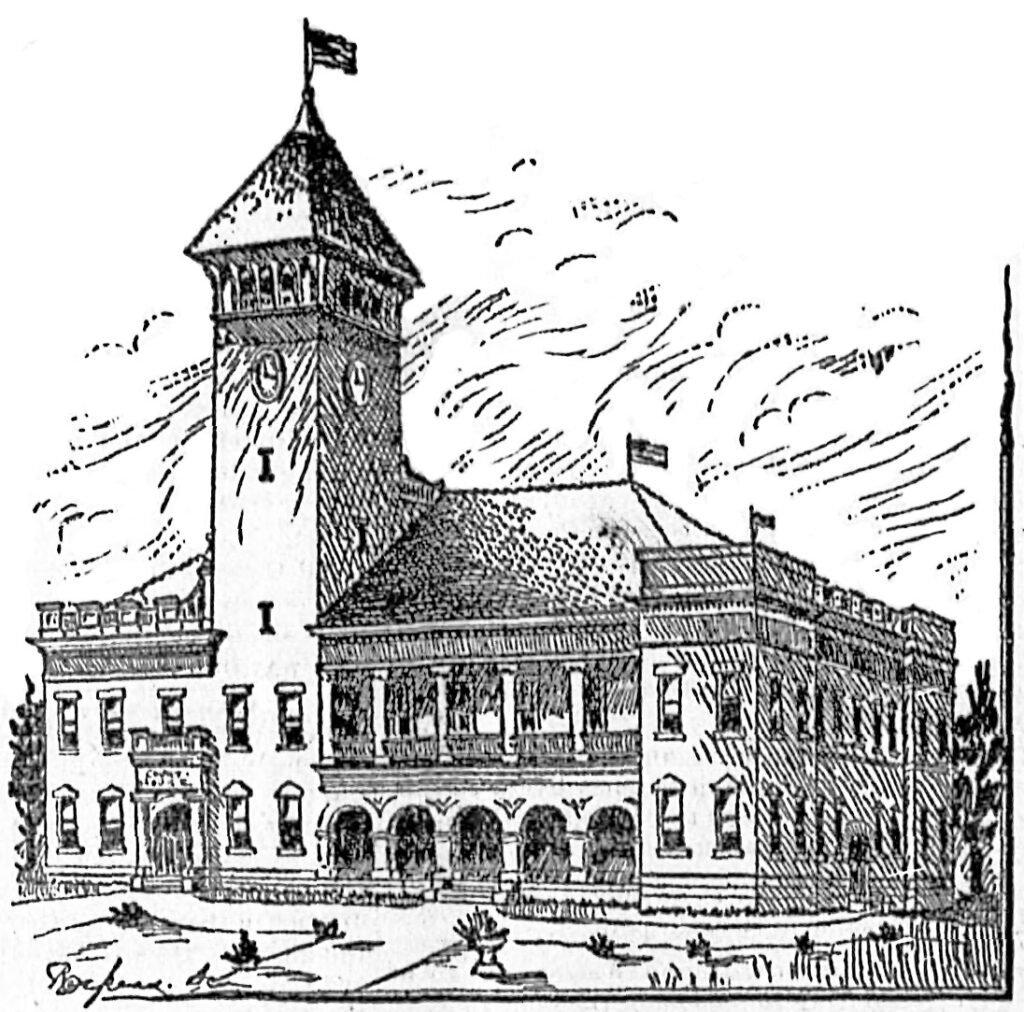

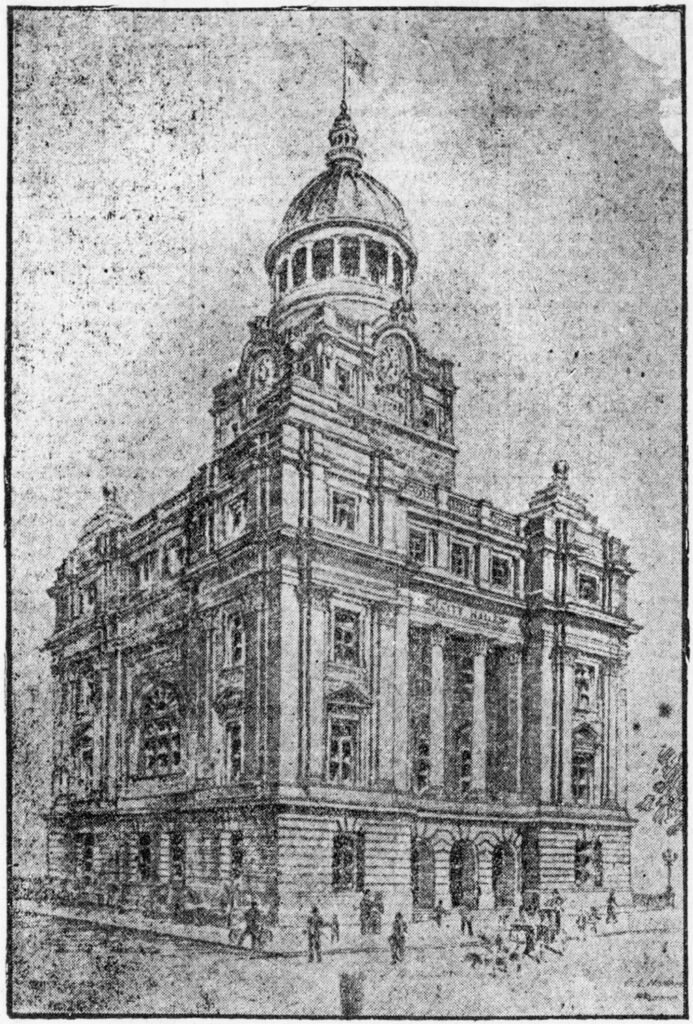

W.W. Goodrich. Proposed design for Kennesaw Mountain Hotel. Kennesaw, Georgia (unbuilt).1 The Background

The following article was published in The Southern Architect in 1893 and written by W.W. Goodrich, an architect who practiced in Atlanta between 1889 and 1895.

The Southern Architect was a monthly trade journal conceived and initially published by Thomas H. Morgan of Bruce & Morgan, patterned after national architectural publications like The American Architect, which gave scant coverage to work in the Southeast, likely because the region’s architecture was — on the whole — terrible.

Speaking to an audience of his peers, Goodrich echoes many familiar complaints shared by professional architects in the late 1800s, when the industry was almost entirely unregulated, and any builder, carpenter, or cabinet-maker could call themselves an architect, copy a building plan from a pattern book, and pass it off as their own.

In a region as vainglorious as the Deep South, where the appearance of wealth and the illusion of status have long been valued over character and substance, the grotesque and excessive designs of substandard architects in the 19th century were not only admired but prized.

Here, Goodrich places the blame for bad architecture squarely on the clients, mocking the poor taste and ludicrous sense of entitlement that have always defined the newly monied. And although he specifically avoids mention of Atlanta (“Every city is cursed with it”, he notes), surely his chief inspiration was the city’s insufferable nouveau riche — and really, there is no other riche in Atlanta.

At the time of this article’s publication, Goodrich’s practice in Atlanta was waning, and he’d no doubt experienced his fill of the city’s empty boasting and repellent arrogance — although he was pretty full of shit himself.

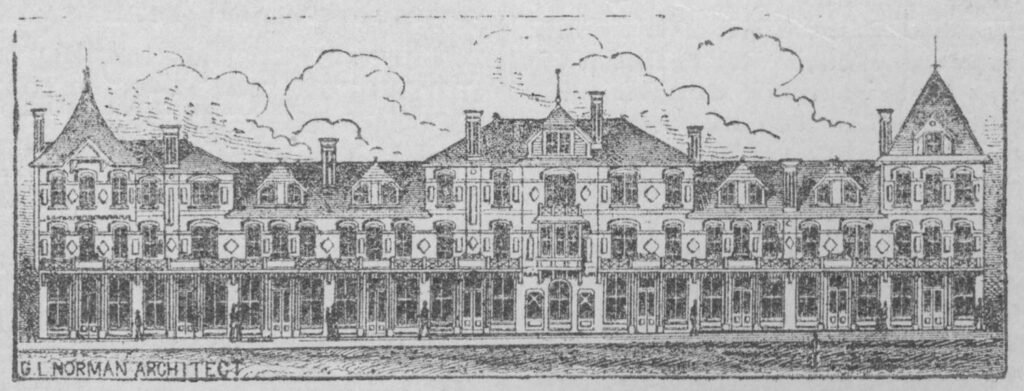

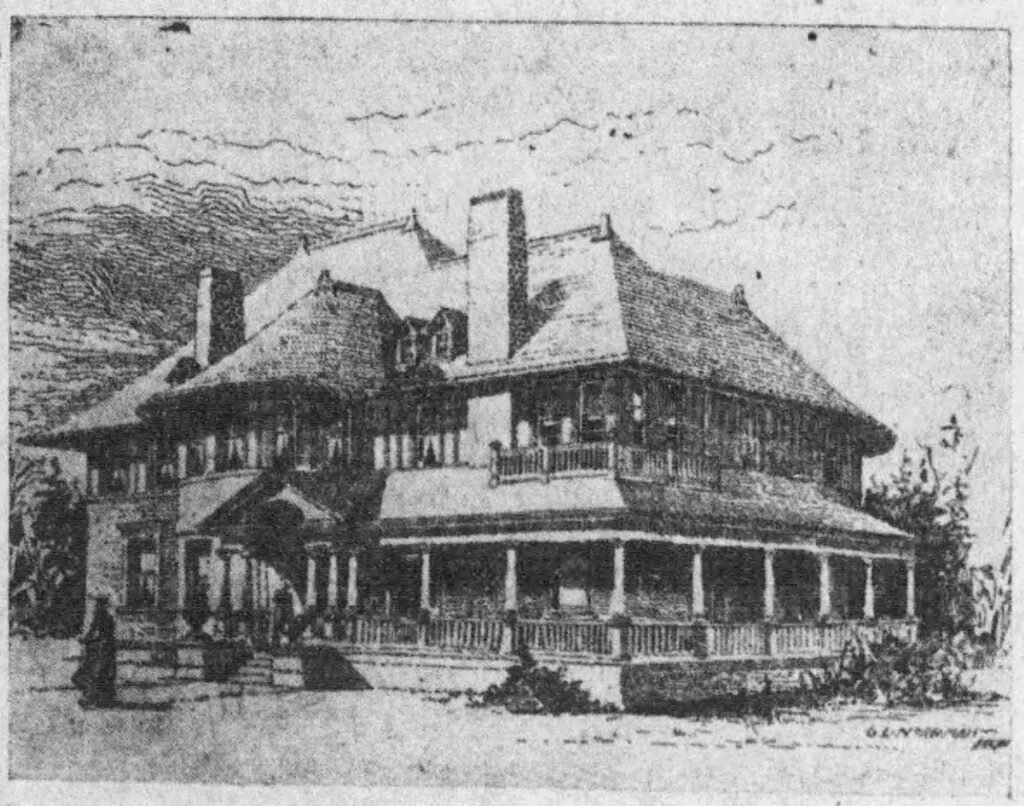

Goodrich’s acerbic, cutting language in this article contrasts sharply with the facile, fawning tone he affected in earlier articles for The Atlanta Journal, more closely resembling the embittered words of another Atlanta architect, G.L. Norrman.

Indeed, the picture painted by Goodrich is bleak: The legitimate architect is resigned to tossing his ideas in the trash, while “Mr. Newrich” demands “another incongruous architectural absurdity that the architect is not responsible for, and should not be blamed for.”

And thus is Atlanta architecture in a nutshell.

Incongruities of Modern Architecture.

There are no incongruities in the designs of modern architects, no fallacious fancies. In writing about modern architects I mean those only who are genuine members of the profession; “Educated for the Profession.” I do not include any one in the noble profession of architecture who is an architect and builder – or one who furnishes designs from books and periodicals.

That there are incongruities in the designs and in the buildings of the so-called “architects and builders” goes without question.

Shameful examples are on every hand of the “architect and builder’s” botch work.

Every city is cursed with it, glaring at the observer at every turn. Any one can detect the carpenter or mason architect. The carpenter architect puts on his facades all the turned work, all the scroll work, all the ornamental work, so-called, that he can possibly get on, i.e., gingerbread work. He will put on domes in unheard of places, towers that look like pigeon houses or children’s playhouses perched upon a roof, straddle of a ridge, or perched in a valley, and in out of the way places.

Any ornamentation that his untutored mind imagines is to him a work of art, and readily finds a resting place on his buildings. An utter lack of harmony, of symmetry and of sympathy is in all his work from cellar to attic, while the real architect is blamed for the unprofessional hideousness of the wood butcher.

The mason architect runs riot on arches that will not carry the load and the thrust flattens them so that they fall by their own weight; arches that gravitate to the ground.

Then there is the civil engineer who sets himself up as an architect without any architectural study whatever. His designs and buildings look like railroad roundhouses or car shops, massive as the pyramids.

I admit the foundation of architecture, “the science of construction,” is engineering, but I do not admit that the ornamental, the harmony of detail, the grouping of mass, the blending of the line between earth and sky is engineering. “It is the music of the soul,” that infinite inspiration of the imagination, that looks in and through all that is beautiful and weaves the warp and woof of the soul’s fancy into a creation; that compels all to know that a master brain has left the imprints of a genius, of a glorious creation, that is a monument for all time to come. To inspiration this creation is simplicity itself, quiet dignity in material, color, form and construction. “A babe can comprehend it.” The simple vine, the color of the lily, the structural construction of canes, the grouping of mass, where weight is required to be sustained, these are the interesting points of the study of the architect.

He does not look after false effects to incorporate them into his building. He avoids them, he shuns them. His whole ambition is to blend his material that the effect shall be an architectural symphony at once attractive but not false, in the which the object is subservient to the client’s demand and the cash account used to the best advantage, so that there shall be no waste.

Clients are solely to blame for all the incongruities of modern architecture, in nearly every instance.

Mr. Newrich or Mrs. Struckile wants a home. It must excel in sublimity the palaces of the world; it must be the most picturesque and distinguished home in the city; the most exquisite charm of the avenue. Mr. T. Square is called upon for designs. He is recognized as an expert and a gentleman of large experience, thoroughly up in his profession. His charges are the regular institute ones, “which all gentlemen should adhere to” without exception.

The newly rich client says: I want so and so – it is my taste; I want my plan like this; at which Mr. T. Square, with his keen discernment of men and things from long practice with an extensive clientele, and with an eye to the etiquette of his most noble calling, says, such and such things won’t work out, won’t harmonize, are not in good taste, are of bad form, and won’t make a pleasing whole, and will be exceedingly incongruous. And he shows the client the utter lack of sense in the client’s demands and wishes, “of course in a gentlemanly way.”

“But, Mr. T. Square, it is my money that pays for what I want, and if you won’t work up my ideas and build as I want, I can get some one that will.”

Poor Mr. T. Square; his professional standing conflicts with his bread and butter; he hates to create a botch, yet his family must have bread; either lose the job, or do work that his very sensitive soul shrinks from touching because he knows that he is and will be held responsible for an incongruous blemish on his architectural escutcheon.

His ability is unquestioned, his record is proof against all vilification, but if he erects the building he will be held responsible for an architectural monstrosity, an incongruous mass. Alas! Others will do it if he won’t, and he quietly puts his views in the wastebasket and is dictated to by Mr. Newrich, and the consequences are another incongruous architectural absurdity that the architect is not responsible for, and should not be blamed for.

W.W. Goodrich2

References

- “Kennesaw Mountain.” The Atlanta Journal, February 4, 1892, p. 5. ↩︎

- Goodrich, W.W. The Southern Architect , Vol. 4, no. 11 (September 1983), p. 317. ↩︎

-

Projects by G.L. Norrman – The Complete List

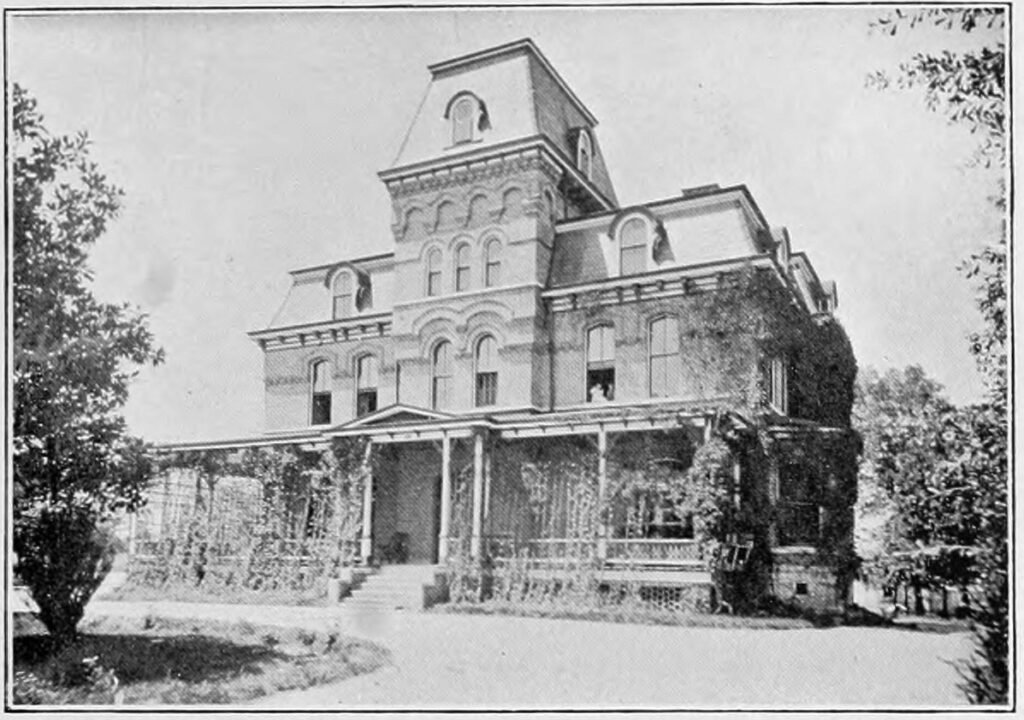

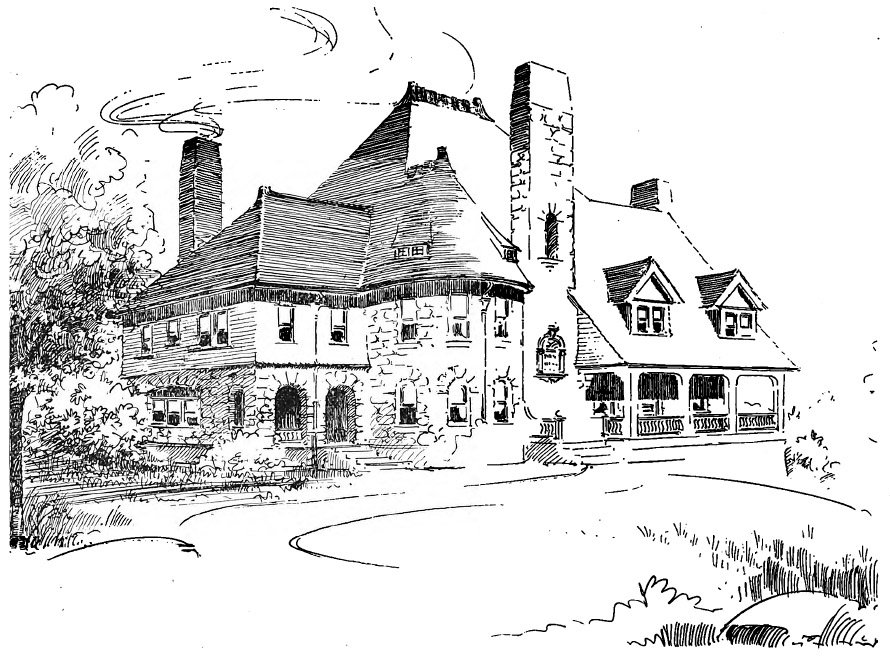

G.L. Norrman. Edward C. Peters House, “Ivy Hall” (1883). Atlanta. Extant Works by G.L. Norrman

Projects listed by date of construction.

- Springwood Cemetery, designed 1876 – Greenville, South Carolina [Map]

- Charles Lanneau Residence, completed 1877 – 417 Belmont Avenue; Greenville, South Carolina [Map]

- William T. Wilkins Residence (attributed), completed 1878 – 105 Mills Avenue; Greenville, South Carolina [Map] [Related Videos: An inside look at the Wilkins House, Tour historic mansion in its new spot]

- Block of 2 storerooms (attributed, altered), completed 1879 – 101 East Main Street; Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

- Newberry Hotel, completed 1880 – 1200 Main Street; Newberry, South Carolina [Map]

- City Hall and Opera House, completed 1882 – 1201 McKibben Street; Newberry, South Carolina [Map] [Related Video: O is for Opera House]

- Stone Hall, completed 1882 – Morris Brown College; Atlanta University Center [Map]

- Edward C. Peters Residence, “Ivy Hall”, completed 1883 – 179 Ponce de Leon Avenue NE; Midtown, Atlanta [Map] [Video: Visit Ivy Hall with Paula Wallace]

- Christ Church, built 1886 – 305 East Central Avenue; Valdosta, Georgia [Map]

- All Saints Church (altered), built 1886 – Sylvania, Georgia. Moved to 530 Greenwood Street, Barnesville, Georgia [Map]

- W.W. Duncan Residence, completed 1886 – 300 Howard Street; Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

- George A. Noble Residence, completed 1887 – 1025 Fairmont Avenue; Anniston, Alabama [Map]

- Printup Hotel (altered), completed 1888 – 135 North 4th Street; Gadsden, Alabama [Map]

- Armstrong Hotel, ground floor facade (altered), building completed 1888 and demolished 1932, ground floor facade incorporated into replacement building – 90 East 2nd Avenue; Rome, Georgia [Map]

- Samuel McGowan Residence, completed 1889 – 211 North Main Street; Abbeville, South Carolina [Map]

- Ervin Maxwell Residence, “Fort View”, completed 1889 – 134 McDonald Street SW; Marietta, Georgia [Map]

- Thomas W. Latham Residence, completed 1889 – 804 Edgewood Avenue NE; Inman Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Atlanta and Edgewood Street Railroad Shed (attributed), completed 1889 – 963 Edgewood Avenue NE, Inman Park, Atlanta [Map]

- 125 Edgewood Avenue (attributed), completed 1889 – Downtown, Atlanta [Map]

- W.L. Glessner Residence (attributed), completed 1890 – 1202 South Lee Street; Americus, Georgia [Map]

- E. A. Hawkins Residence, completed 1890 – 406 East Church Street; Americus, Georgia [Map]

- Residence for East Atlanta Land Company, completed 1890 – 897 Edgewood Avenue NE, Inman Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Home for East Atlanta Land Company, completed 1890 – 882 Euclid Avenue NE; Inman Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Standard Wagon Company Building (attributed), completed 1891 – 58 Walton Street NW; Fairlie-Poplar, Atlanta [Map]

- M. B. Council Residence (attributed), completed 1891 – 602 Rees Park; Americus, Georgia [Map]

- City Hall and Fire Station, completed 1891 – 109 North Lee Street; Americus, Georgia [Map]

- Henry Street School, completed 1892 – 115 West Henry Street; Savannah, Georgia [Map]

- W. P. Carrington Residence, completed 1892 – 2 Meeting Street; Charleston, South Carolina [Map] [Related Video: Two Meeting Street Inn]

- Windsor Hotel, completed 1892 – 125 West Lamar Street; Americus, Georgia [Map]

- College Inn (altered), completed 1892 – 2 Epworth Dorm Lane, Duke University; Durham, North Carolina [Map]

- Edgewood Avenue Grammar School, completed 1892 – 729 Edgewood Avenue NE; Inman Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Gatewood Residence, expansion and renovation (attributed) of home built circa 1850, completed 1892 – 128 Georgia Highway 49 North; Americus, Georgia [Map]

- John T. Taylor Residence (attributed), completed 1892 – 603 South Lee Street; Americus, Georgia [Map]

- George W. Williams Residence, Jr. expansion and renovation (attributed) of home built circa 1770, completed 1892 – 15 Meeting Street; Charleston, South Carolina [Map]

- Fannie Lou Cozart Residence renovation and expansion of home built circa 1825, completed 1893 – 211 East Court Street, Washington, Georgia [Map]

- J.C. Simonds Residence, renovation and expansion of home originally built in 1856, completed 1893 – 29 East Battery Street; Charleston, South Carolina [Map] [Related Video: 29 E Battery Porcher-Simons house Charleston]

- R.O. Barksdale Residence, completed 1893 – 33 Lexington Avenue; Washington, Georgia [Map]

- C. D. Hurt Residence (attributed), completed 1893 – 36 Delta Place; Inman Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Sixteenth Street School, completed 1893 – 1532 3rd Avenue; Columbus, Georgia [Map]

- W.B. Chisolm Residence, expansion and renovation (attributed) of home built circa 1816, renovation circa 1893 – 68 Meeting Street; Charleston, South Carolina [Map]

- T.P. Ivy Residence, completed 1895 – 785 Piedmont Avenue NE; Midtown, Atlanta [Map]

- Citizens Bank, completed 1895 – 15 Drayton Street; Savannah, Georgia [Map]

- Wellhouse and Son Building, completed 1896 – 263 Decatur Street SE; Downtown, Atlanta [Map]

- Milton Dargan Residence, completed 1897 – 767 Piedmont Avenue NE; Midtown, Atlanta [Map]

- W.L. Reynolds Residence, completed 1897 – 761 Piedmont Avenue NE; Midtown, Atlanta [Map]

- Cleveland Law Range (attributed), completed 1899 – 175 Magnolia Street; Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

- Anderson Memorial Methodist Episcopal Church, completed 1899 – 312 Sycamore Street; Decatur, Georgia [Map]

- Henry D. Stevens Residence, renovation and expansion of home built in 1866, completed 1899 – 303 East Gaston Street; Savannah, Georgia [Map]

- Arthur B.M. Gibbes Residence, completed 1900 – 105 East 37th Street; Savannah, Georgia [Map]

- 38th Street School, completed 1901 – 315 West 38th Street; Savannah, Georgia [Map]

- Candler Hall, completed 1902 – University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia [Map]

- Denmark Hall, completed 1902 – University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia [Map]

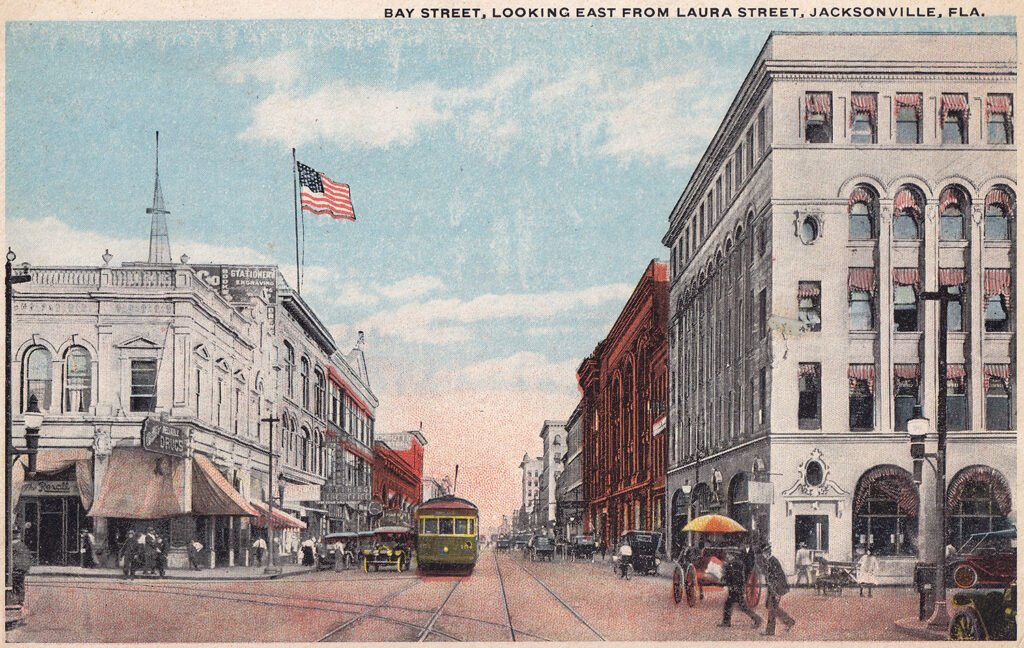

- Bisbee Building, completed 1902 – 57 West Bay Street; Jacksonville, Florida [Map]

- Eureka Hotel, completed 1902–03 – 104 East Pickens Street; Abbeville, South Carolina [Map] [Related Video: Belmont Inn]

- Lawrence McNeil Residence, completed 1904 – 513 Whitaker Street; Savannah, Georgia [Map] [Related Video: Savannah, GA, Colonial Mansion Tour]

- C.W. Dupre Residence (attributed), completed 1904 – 393 Cherokee Street NE; Marietta, Georgia [Map]

- First Baptist Church, completed 1905-16 – 305 South Perry Street; Montgomery, Alabama [Map]

- Barnard Street School, completed 1906 – 212 West Taylor Street; Savannah, Georgia [Map]

- E. W. McCerren Apartments, “The Chester”, completed 1907 – 223 Ponce De Leon Avenue NE; Midtown, Atlanta [Map]

- Piedmont Driving Club renovation and expansion (altered), originally designed by Norrman in 1887, built from a home constructed in 1868; partially destroyed by fire on January 11, 1906; rebuilt and expanded to Norrman’s design from 1906-07 – 1215 Piedmont Avenue NE, Atlanta [Map]

- Palmer Apartments, completed 1908 – 81 Peachtree Place NE; Midtown, Atlanta [Map]

- E.S. Ehney Residence, completed 1908 – 223 15th Street NE; Ansley Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Ella B. Wofford Residence, completed 1909 – 571 East Main Street; Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

- Central Methodist Church, transepts and renovation, completed 1910 by Hentz & Reid – 233 North Church Street; Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

Lost Works by G.L. Norrman

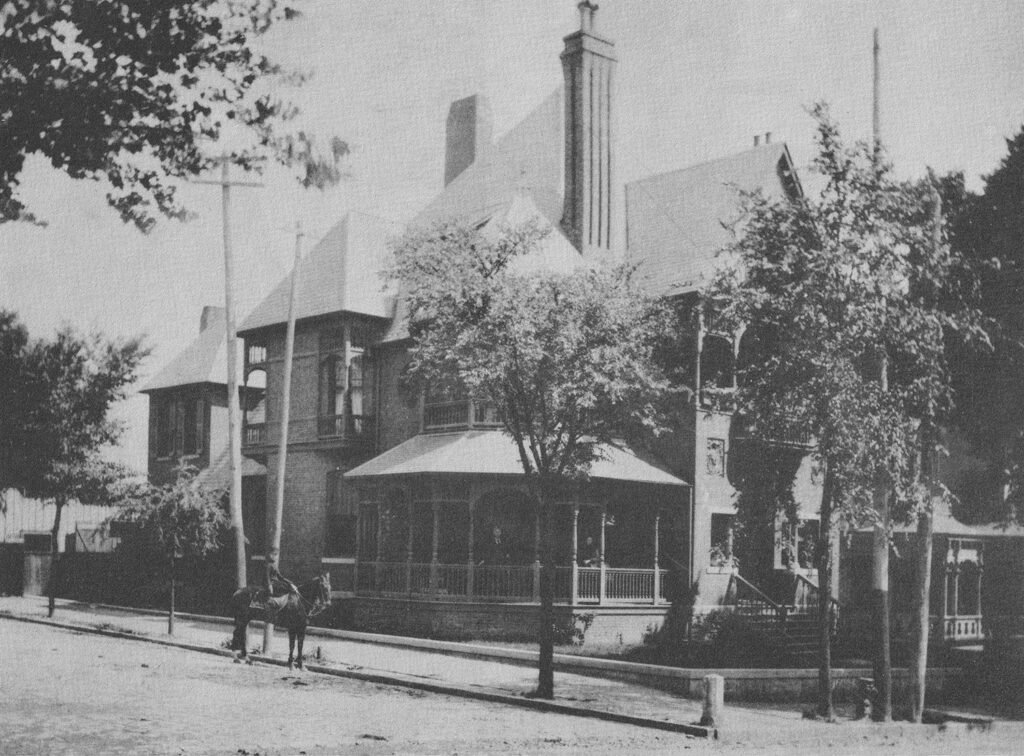

G.L. Norrman. Spartan Inn (1880-1910). Spartanburg, South Carolina. The following projects are listed by date of construction. Addresses use original street names, and for Atlanta projects, the addresses use the original numbers designated before the citywide renumbering in 1926.

- Saint Mary’s Catholic Church, built 1876 – SE corner of Hampton and Lloyd Streets, Greenville, South Carolina. Norrman was the supervising architect, with the design credited to an unnamed Charleston architect. The building was moved in 1885 to 438 West Washington Street, then moved 50 yards in 1902 and rechristened Columbus Hall. The building was later demolished. [Map]

- Dr. C.A. Henderson Residence, built 1876 – West McBee Avenue (likely 142 West McBee Avenue); Greenville, South Carolina [Map]

- Franklin Coxe, Jr. Residence, built 1876-77 – NE Corner of Tryon and 9th Streets; Charlotte, North Carolina [Map]

- John J. Blackwood Residence, built 1876 – Greenville, South Carolina

- George P. Wells Residence, built 1877 – Buncombe Street, west of Academy Street; Greenville, South Carolina [Map]

- Frank Coxe, Jr. Residence, built 1877-78 – Greenville, South Carolina

- L.A. Mills Residence, built May 1879 – Main Street, Spartanburg, South Carolina – later site of Mills Avenue, location of Ella B. Wofford Residence [Map]

- Merchant’s Hotel/Spartan Inn, built May 1879 to January 1880; destroyed by fire on April 22, 1910 – Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

- Spartanburg Opera House, built 1880 and demolished 1907 – Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

- Methodist Mission Church, “St. Annie’s Chapel”, built 1879-1880 – Church Street; Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

- House at Tryon, North Carolina, building date unknown. Referenced by Norrman on January 14, 1892: “I built … a house on the mountain side at Tryon, S.C. and it was struck by a storm and carried away. The chimney was demolished, but the house rolled down the mountain side without breaking.”

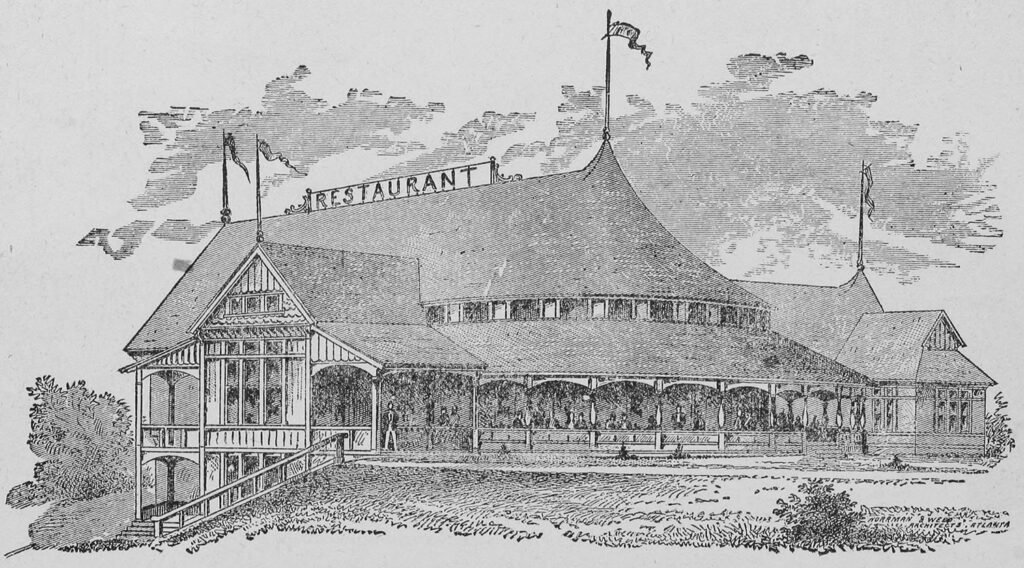

Norrman & Weed. Exposition Restaurant at International Cotton Exposition (1881). Atlanta. Norrman & Weed (1880-1881)

- John B. Steele Residence, built 1880 and destroyed by fire on December 24, 1890 – 71 White Pine Street, Asheville, North Carolina [Map]

- Faith Cottage at Thornwell Orphanage, built 1880-81 – Clinton, South Carolina [Map]

- Main Building at International Cotton Exhibition, built in 1881 and destroyed by fire on August 5, 1971 – Oglethorpe Park, Atlanta. W.H.H. Whiting was the architect, and Norman & Weed were supervising architects. [Map]

- Art and Industry Pavilion at International Cotton Exhibition, built 1881 and demolished by 1971 – Oglethorpe Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Carriage Annex at International Cotton Exhibition, built 1881 and demolished by 1971 – Oglethorpe Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Agricultural Annex at International Cotton Exhibition, built 1881 and demolished by 1971 – Oglethorpe Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Grand Hotel at International Cotton Exhibition, built 1881 and demolished by 1971 – Oglethorpe Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Department of Public Comfort at International Cotton Exhibition, built 1881 and demolished by 1971 – Oglethorpe Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Depot at International Cotton Exhibition, built 1881 and demolished by 1971 – Oglethorpe Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Exposition Restaurant at International Cotton Exhibition, built 1881 and demolished by 1971 – Oglethorpe Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Press Pavilion at International Cotton Exhibition, built 1881 and demolished by 1971 – Oglethorpe Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Nathaniel P.T. Finch Residence, built 1881 – 388 Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

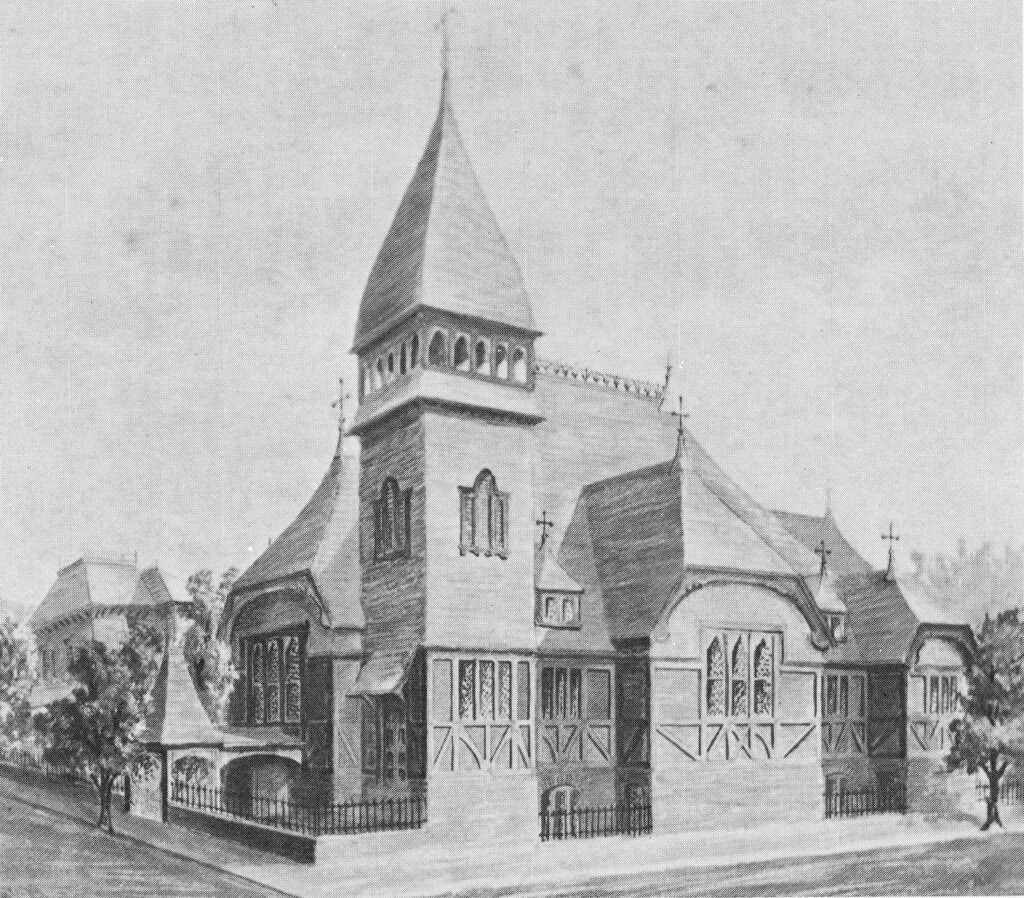

Humphries & Norrman. St. Luke’s Cathedral (1883-1906). Atlanta. Humphries & Norrman (1882-1883)

- Daniel N. Speer Residence, built 1882 – 486 Peachtree Street, SW corner of Peachtree and Linden Streets, Atlanta – later site of Emory University Hospital Midtown [Map]

- C.T. Swift Residence, built 1882 and likely demolished circa 1928 for the construction of Fox Theatre – 38 Kimball Street, Atlanta. This is not the home C.T. Swift built on Capitol Avenue in 1885, designed by L.B. Wheeler of Atlanta. [Map]

- John Milledge Residence, built 1883 – 120 East Peters Street, NE corner of East Peters Street and Capitol Place, Atlanta – later site of 2 Capitol Square SW, Downtown [Map]

- Block of 3 tenement houses for John Milledge, built 1882 – Cooper Street, Atlanta

- John H. Glover Residence, built 1882 – 135 South Pryor Street, near NW corner of Pryor and East Peters Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- William D. Ellis House, built 1882 and demolished for construction of Atlanta Expressway (I-75/85) – 193 Washington Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Unitarian Church of Our Father, built 1883 – SW corner of Church and Forsyth Streets, Atlanta – later site of Atlanta-Fulton Public Library, Central Library, Downtown [Map]

- Paul Romare Residence, built 1883 – 117 South Pryor Street, SW corner of South Pryor and Peters Streets [Map]

- James C. Daniel Residence, built 1883 – 196 Gordon Street, West End, Atlanta [Map]

- St. Luke’s Cathedral, built 1883 and demolished 1906 – NE corner of North Pryor and Houston Streets, Atlanta – later site of Georgia-Pacific Center, Downtown [Map]

- Gate City National Bank, built 1883 – SW corner of Alabama and Pryor Streets, Atlanta – later site of Underground Atlanta, Downtown [Map]

- Alteration of front exterior for J.M. High & Company store, built 1883 – 46-48 Whitehall Street, Atlanta [Map]

- William Dickson Residence, built 1884 and likely demolished for construction of Atlanta Expressway (I-75/85) – 378 Peachtree Street, Atlanta. William Halsey Wood of New York was the architect; Humphries & Norman were supervising architects.

- Charles W. Crankshaw Residence, built 1883 – 119 Nelson Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Angier Family residential block, built 1883 and demolished 1951 – 26-30 Capitol Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- Freeman & Crankshaw jewelry store, built 1883 – 31 Whitehall Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Thomas H. Blacknall Residence, built 1883 and likely demolished for construction of East-West Expressway (I-20) – 56 Park Avenue, SE corner of Park and Lee Streets, West End, Atlanta [Map]

- Dr. Spalding Residence, built 1883 – 484 Peachtree Street, NE corner of Peachtree and Howard Streets, Atlanta – later site of Emory University Hospital Midtown [Map]

- William H. Venable Residence, built 1883 – 19 Forrest Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- Ponce De Leon Springs pavilion, built 1883 and demolished circa 1914 – later site of Sears, Roebuck & Company Building, Atlanta. [Map]

- West End Academy, built 1883-4 and demolished circa 1911 – Lee Street, West End, Atlanta [Map]

- Dr. E.W. Roach Residence, built 1883 and likely demolished for construction of Atlanta Expressway (I-75/85) – 95 Capitol Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- Horace Bumstead Residence, “Bumstead Cottage”, built 1883 and demolished by 1929 – 169 Vine Street, NE corner of Vine Street and University Place, Atlanta [Map]

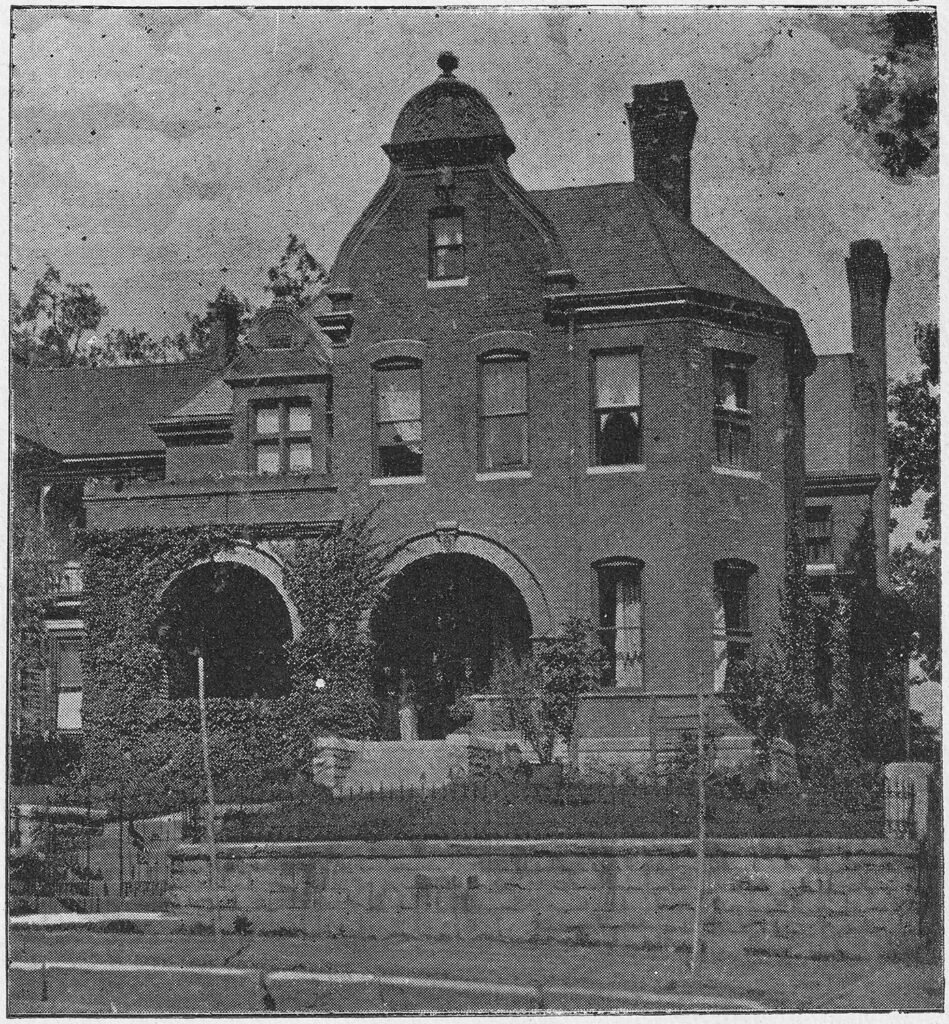

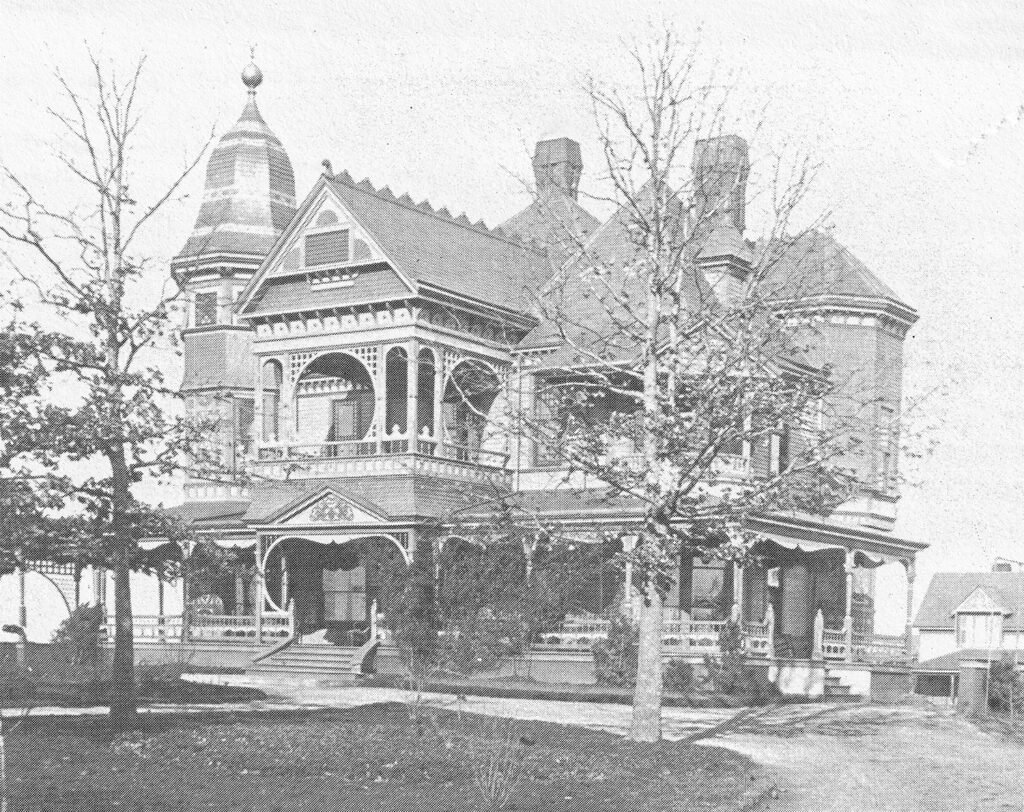

G.L. Norrman. W.S. Everett Residence (1884). Atlanta. G.L. Norrman (1883-1905)

- William S. Everett Residence, built 1884 – 278 Peachtree Street, Atlanta – later site of Atlanta Expressway (I-75/85) [Map]

- Homer G. Barber Residence, built 1884 – 147 Forrest Avenue, Atlanta – later site of Georgia Power Company, Old Fourth Ward [Map]

- Robert A. Hemphill Residence, built 1884 – 231 Peachtree Street, Atlanta – later site of SunTrust Plaza, Downtown [Map]

- Grant Park pavilion, built 1884 – Grant Park, Atlanta [Map]

- William A. Osborn Residence, built 1884 – 194 Jackson Street, Atlanta

- Benjamin F. Abbott Residence, built 1884 – 171 Peachtree Street, Atlanta – later site of Peachtree Center, Downtown. Moser & Lind of Atlanta designed plans for this home in 1883, although it appears Norrman was responsible for the completed project. In 1892, Abbott moved to a new home built on “far-out Peachtree”, also likely designed by Norrman. In 1895, he married Josephine Richards, widow of R.H. Richards, moving into the Richards home on Peachtree Street, designed by Norrman in 1885. [Map]

- Willard H. Nutting Residence, built 1885 – 45 Merritts Avenue, Atlanta – later site of Renaissance Park, Old Fourth Ward [Map]

- Dr. James B. Baird Residence and Office, built 1885 – 105 Capitol Square, Atlanta – later site of Paul D. Coverdell Legislative Office Building, Downtown [Map]

- Block of 2 stores for Major Bridwell, built 1885 – 160 and 162 Decatur Street, NE corner of Decatur and Butler Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Herman Franklin Residence, built 1885 and likely demolished for construction of East-West Expressway (I-20) – 239 Rawson Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Cheshire Residence, built 1885 – Peachtree Street, Atlanta

- Willis F. Peck Residence, built 1885 – 335 Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

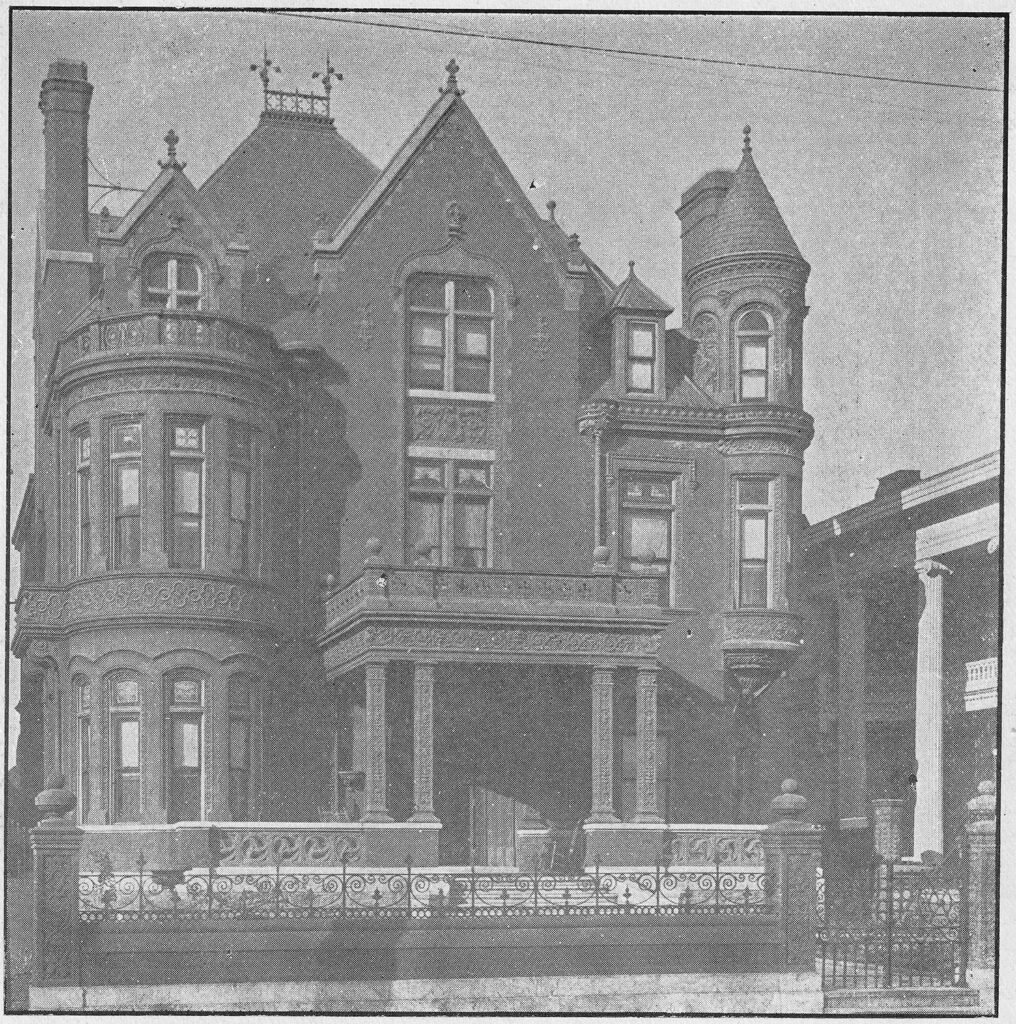

G.L. Norrman. R.H. Richards House (1885-1925). Atlanta. - R. H. Richards Residence, built 1885 and demolished 1925 for construction of Davison-Paxon-Stokes Company building – 190 Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Residential duplex for Miles & Horn, built 1885 – SE corner of Walton and Spring Streets, Atlanta – later site of Centennial Tower, Downtown [Map]

- Pavilion and landscape improvements, built 1885 – Salt Springs, Georgia – later Lithia Springs, Georgia [Map]

- Kennedy Free Library, built 1885 – NE corner of Public Square; Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

- Atlanta National Bank renovation, 1886 – 15 East Alabama Street, Atlanta – later site of Underground Atlanta, Downtown [Map]

- Arthur H. Locke Residence, built 1886 and demolished circa 1911 for the construction of Davis-Fischer Sanatorium – 19 Cox Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Willis E. Ragan Residence, built 1886 and demolished circa 1928 for the construction of Fox Theatre – 574 Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

- S.H. Phelan Residence, built 1886 – 304 Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

- James Akers Residence, built 1886 and likely demolished circa 1919 for United Motors Building – 333 Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Martin Grahame Residence, “Muirdrum”, built 1886 – Carlier Springs, near Rome, Georgia – later site of Callier Springs Country Club [Map]

- Sweet Water Park Hotel, built 1886-87 and destroyed by fire on January 12, 1912 – Lithia Springs, Georgia [Map]

G.L. Norrman. Main Building at Piedmont Exposition (1887). Atlanta. - Main Building at Piedmont Exposition, built 1887 and converted into Transportation Building for Cotton States and International Exposition, 1895; destroyed by fire on November 15, 1901 – Piedmont Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Machinery Hall at Piedmont Exposition, built 1887 and demolished February 1895 – Piedmont Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Agricultural Hall at Piedmont Exposition, built 1887 and demolished 1895 – Piedmont Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Grandstand at Piedmont Exposition, built 1887 and converted into Auditorium for Cotton States and International Exposition, 1895; demolished 1908 – Piedmont Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Depot at Piedmont Exposition, built 1887 and demolished 1895 – Piedmont Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Restaurant at Piedmont Exposition, built 1887 and demolished 1895 – Piedmont Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Public Comfort Building at Piedmont Exposition, built 1887 and demolished 1895 – Piedmont Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Main Entrance for Piedmont Exposition, built 1887 and demolished February 20, 1895 – Piedmont Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Capitol City Bank, built 1887 – 23 Whitehall Street, NW corner of Whitehall and Alabama Streets [Map]

- J.H. Nunnally Residence, built 1887 and likely demolished for construction of Atlanta Expressway (I-75/85) – 285 Peachtree Street, SE corner of Peachtree and Currier Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Renovation of F.T. Powell Residence, completed 1887 and likely demolished for construction of Atlanta Expressway (I-75/85) – 281 Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Andrew M. Bergstrom Residence, built 1887 – 114 South Pryor Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Bath house, built by 1887 – Salt Springs, Georgia (now Lithia Springs, Georgia)

- Jack King Residence, built 1887 – Howard Street (later East 2nd Avenue), Rome, Georgia

- George Lewis Residence, built 1887 and demolished before 1963 – 601 East Park Avenue, NE corner of Park Avenue and North Gadsden Street, Tallahassee, Florida [Map]

- DeForest Allgood Residence, built 1887 and destroyed by fire on February 24, 1903 – Trion, Georgia

G.L. Norrman. Armstrong Hotel (1888-1934). Rome, Georgia. - Armstrong Hotel, Opened October 1, 1888, and demolished in 1934, with a portion of the ground floor incorporated into the new building – East 2nd Avenue, Rome, Georgia [Map]

- Hebrew Orphans’ Home, built 1888-9 and demolished circa January 1974 following construction of Our Lady of Perpetual Help Home – 478 Washington Street, Atlanta [Map]

- James C. Freeman Residence, built 1889-90 – 759 Peachtree Street, NE corner of Peachtree and 8th Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- George V. Gress Residence, built 1889-90 – 301 Peachtree Street, Atlanta – later site of SunTrust Plaza, Downtown [Map]

- William J. Speer Residence, built 1889-90 – 544 Peachtree Street, NW corner of Peachtree Street and North Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- Laboratory for Ewbank’s Topaz Cinchona Cordial, built 1889 – Marietta Street, Atlanta (Building partially visible on far right of linked image, with “Remedies” sign) [Map]

- Block of 4 tenement houses for Robert Winship, built 1889 – SE or NE corner (possibly both) of Cain and Ivy Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- T.A. Hammond Residence, built 1889 – 151 Spring Street, Atlanta – later site of Atlanta Merchandise Mart, Peachtree Center [Map]

- Double tenement house, built 1889 – Forsyth Street, Atlanta

- Willard H. Nutting Residence, built 1889 – 51 Merritts Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- J.R. Nutting Residence, built 1889 – 46 Merritts Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- Willis E. Venable Residence, built 1889 — 182 Gordon Street, West End, Atlanta [Map]

- Double houses for Jacob Haas, built 1889 — 285-303 Washington Street [Map]

- Exchange Building, built 1889 – intersection of Edgewood Avenue and Gilmer Street, Atlanta [Map]

- George V. Gress Zoo, built 1889 – Grant Park, Atlanta – later site of Zoo Atlanta [Map]

- Dr. W.D. Bizzell Residence, additions built 1889 – 53 Forrest Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- H.M. Potts Residence, built 1889 – 248 Gordon Street, SE corner of Gordon Street and Gordon Place, West End, Atlanta [Map]

- Joseph P. Thompson Residence, “Brookwood”, built 1889 and demolished 1907 – Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

G.L. Norrman. Belleveue Hotel (1889-1912). Gadsden, Alabama. - Bellevue Hotel, built 1889 and destroyed by fire on June 4, 1912 – Bellevue Drive, Gadsden, Alabama [Map]

- George V. Gress business block, built 1890 – 89-91 Whitehall Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Hirsch Brothers clothing store, built 1890; top 3 floors demolished and lower floors altered 1935 – 40-44 Whitehall Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Isaac Liebman Residence, built 1890 – 248 Washington Street, NE corner of Washington and Richardson Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Augustus O.M. Gay Residence, built 1890 and likely demolished for construction of Atlanta Expressway (I-75/85) – 323 Spring Street, NE corner of Spring and West Pine Streets, Atlanta

- Harvey Johnson Residence, built 1890 – 730 Peachtree Street, SW corner of Peachtree and 7th Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Edmund Berkeley Residence, built 1890 – 311 West Peachtree Street, SE corner of West Peachtree and 3rd Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- James C. Daniel Residence, built 1890 – 196 Gordon Street, West End, Atlanta [Map]

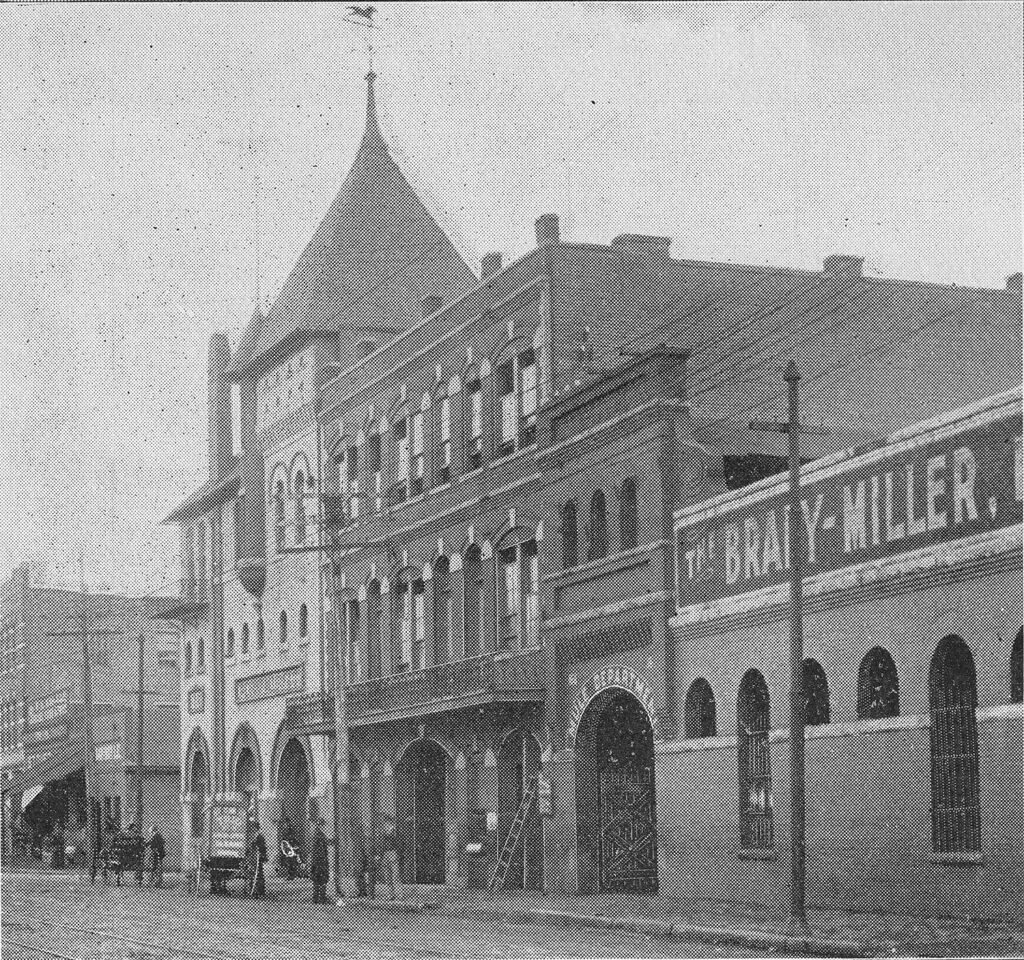

G.L. Norrman. Brady-Miller Feed & Sale Stables (1890-1936). Atlanta. - Brady-Miller Feed & Sale Stables, built 1890 and demolished January 1936 – SW corner of Marietta and Bartow Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Alexander King Residence, built 1890 – 894 Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Residence constructed for Crankshaw & Company, built 1890 – Corner Edgewood Avenue and Jackson Street, likely NE corner lot at 342 Edgewood Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- A.E. Thornton Residence, “Thornhurst”, built 1890 – Vinings, Georgia

- Bartow M. Blount Residence, built 1890 – SW corner of Main Street and Thompson Avenue, East Point, Georgia [Map]

- Jackson Street School, originally built 1859, renovation and addition of new north and south classroom wings designed by Norrman in 1890; demolished May 1914 for construction of Furlow Grammar School – NW corner of South Jackson and College Streets, Americus, Georgia [Map]

- Cottage at 36 Powers Street for Porter Brothers and Black, and resided in by John Black, built 1890 – SW corner of Powers and Spring Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Cottage at 38 Powers Street for Porter Brothers and J.R. Black, built 1890 – near SW corner of Powers and Spring Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Cottage at 42 Powers Street for Porter Brothers and J.R. Black, built 1890 – near SW corner of Powers and Spring Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Cottage at 46 Powers Street for Porter Brothers and J.R. Black, built 1890 – near SW corner of Powers and Spring Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Cottage at 48 Powers Street for Porter Brothers and J.R. Black, built 1890 – near SW corner of Powers and Spring Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Cottage at 50 Powers Street for Porter Brothers and J.R. Black, built 1890 – near SW corner of Powers and Spring Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Cottage at 228 Spring Street for Porter Brothers and J.R. Black, built 1890 – near SW corner of Powers and Spring Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Cottage at 232 Spring Street for Porter Brothers and J.R. Black, built 1890 – near SW corner of Powers and Spring Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Guy Louis Winthrop Residence, built 1890 – 610 North Monroe Street, Tallahassee, Florida

G.L. Norrman. Duncan Building (1891-1975). Spartanburg, South Carolina. - Latta Park Pavilion, also known as “4 C’s Pavilion” (Charlotte Consolidated Construction Company), opened May 20, 1891, and was demolished in 1911 – Dilworth, Charlotte, North Carolina [Map]

- Thompson & Anderson jewelry store interiors, opened October 1, 1891, inside Windsor Hotel and closed March 17, 1893 – 404 Jackson Street, Americus, Georgia [Map]

- Hotel Carrolina, built 1891 and demolished 1907 – NE corner of Corcoran and Peabody Streets; Durham, North Carolina [Map]

- Duncan Building, built 1891, gutted by fire on March 3, 1975, and demolished in September 1975 – NE corner of Morgan Square and Magnolia Street; Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

- Dime Savings Bank, building renovated and given a new facade, 1891-92; the structure still exists, but all elements of Norrman’s design have been removed – 280 King Street, Charleston, South Carolina [Map]

- St. Mary’s Catholic Church, built in 1892, demolished in February 1961 for a new sanctuary – 332 South Lee Street; Americus, Georgia [Map]

- Police station adjoining city hall, completed September 1891 and demolished 1948 – North Lee Street, Americus, Georgia [Map]

- College Hall at West Florida Seminary (now Florida State University), built 1891 and demolished 1912 – Tallahassee, Florida [Map]

- Ware County Courthouse, built 1891 and demolished 1957 – Waycross, Georgia [Map]

G.L. Norrman. John D. Turner House (1892). Atlanta. - Office of G.L. Norrman, built 1892 – Suites 801, 802, and 804, Equitable Building, Atlanta [Map]

- Atlanta Police Headquarters, built 1892 and demolished 1959 – 171-179 Decatur Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Paul Romare House, built 1892 – 17 East North Avenue, Atlanta – later site of Bank America Plaza, SoNo [Map]

- T. Howard Bell House, built 1892 – 665 Peachtree Street, NE corner of Peachtree and Fifth Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Renovation of Chamber of Commerce building, 1892 – NE corner of Hunter and Pryor Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Dr. John D. Turner House, built 1892 – 50 Cone Street, west corner of Cone and Luckie Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Hebrew Benevolent Congregation, originally built in 1875, renovated according to Norrman design in 1892 – SE corner of South Forsyth and Garnett Streets, Atlanta – later site of Garnett Station, Downtown [Map]

- Sumter County Jail, built in 1892 and demolished in 1959 for a parking lot – North Lee Street, Americus, Georgia [Map]

- City Hall, built 1893 – SW corner of Tryon and 5th Streets; Charlotte, North Carolina [Map]

- Peck Building, built 1893 and demolished 1941 – Intersection of Peachtree, Pryor, and Houston Streets, Atlanta [Map]

G.L. Norrman. Formwalt Street School (1893-1969). Atlanta. - Formwalt Street School, built 1893 and demolished 1969 – NE corner of Formwalt and Eugenia Streets [Map]

- Young Men’s Library Association Library, renovation and expansion of existing residential structure in 1893, demolished 1923 – 101 Marietta Street, NW corner of Marietta and Cone Streets, Atlanta – later site of Centennial Tower [Map]

- John Silvey & Company Building, built 1893-94 and demolished 1936 for construction of Olympia Building – 6-8 Decatur Street and 5-7 Edgewood Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

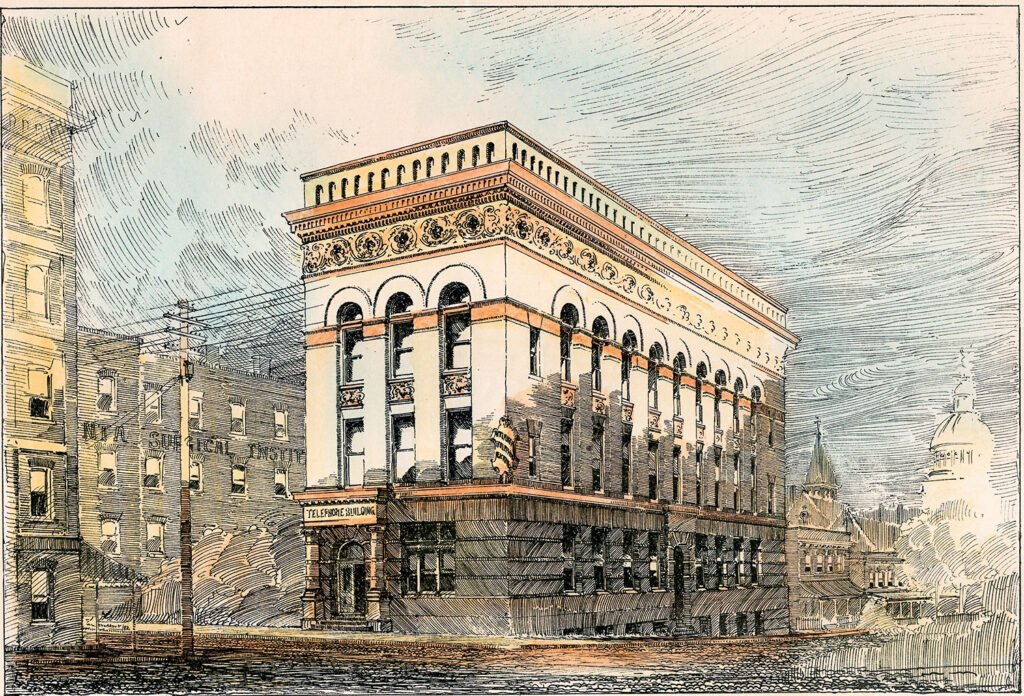

- Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph Building, built 1893-94 and demolished 1952 – 78 South Pryor Street, NE corner of Mitchell and Pryor Streets, Atlanta – later site of Fulton County Civil-Criminal Court Building [Map]

- Atlanta National Bank, built 1893 – 15 East Alabama Street, Atlanta – later site of Underground Atlanta [Map]

- Merchants Bank – existing building remodeled with new facade to Norrman’s design 1893, demolished 1909 for construction of Third National Bank – 45 North Broad Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Hugh L. McKee Residence, built 1893 and demolished before 1990 – 701 Piedmont Avenue, SE corner of Piedmont Avenue and 7th Street, Atlanta [Map]

- William Alanson Gregg Residence, built 1893 and demolished 1958 for construction of East-West Expressway (I-20) – 176 Capitol Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- Edwin C. Merry Residence, built 1893 and likely demolished for construction of East-West Expressway (I-20) – 144 Lee Street, West End, Atlanta [Map]

G.L. Norrman. Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph Building (1894-1952). Illustration by W.L. Stoddart. - Norcross Building, built 1894 and destroyed by fire on December 9, 1902 – 2-4 Marietta Street and 12-20 Peachtree Street, SW corner of Peachtree and Marietta, Atlanta [Map]

- R.L. Foreman Residence, built 1894 – 130 Peeples Street, SE corner of Peeples and Oak Streets, West End, Atlanta [Map]

- Dr. J.S. Todd Residence, built 1894 – 322 Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Hotel Jackson – existing office building constructed in 1889, renovated and converted to a hotel in 1895 according to Norrman’s design – NE corner of Pryor and Alabama Streets, Atlanta – later site of Underground Atlanta [Map]

- Georgia Manufacturers’ Building at Cotton States and International Exposition, built 1895 and demolished January 18, 1896 – Piedmont Park, Atlanta [Map]

- Chinese Village at Cotton States and International Exposition, built 1895 and demolished January 1896 – Piedmont Park, Atlanta [Map]

- New York Herald Building at Cotton States and International Exposition, built 1895 and demolished January 1896 – Piedmont Park, Atlanta [Map]

G.L. Norrman. Hebrew Orphans’ Home, original building (right, 1889-1974) and addition (left, 1895-1974). Atlanta. - Hebrew Orphans’ Home addition, built 1895 and demolished circa January 1974 following construction of Our Lady of Perpetual Help Home – 478 Washington Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Charles A. Read Residence, built 1895 – 309 West Peachtree Street, near SE Corner of West Peachtree and 3rd Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Preston Arkwright Residence, built 1895 – SW corner of Juniper and 7th Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Preston Arkwright servants’ house, built 1895 – SW corner of Juniper and 7th Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Frederick Wagner Residence, built 1895 – 270 Gordon Street, SE corner of Gordon and Peeples Streets, West End, Atlanta [Map]

- St. Julien Ravenel Residence, built 1895 – 159 East North Avenue, SW corner of North Avenue and Myrtle Street [Map]

- Virgil O. Hardon Residence, built 1895 – 283 Peachtree Street [Map]

- St. Mary’s Chapel, built 1891-96 – SE corner of 3rd Avenue and 17th Street, Columbus, Georgia [Map]

- Restaurant at Kimball House Hotel – existing structure renovated according to Norrman’s design in 1896, demolished June 1959 – Block bound by Peachtree, Wall, Lloyd, and Decatur Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- W.D. Ellis, Jr. Residence, built 1896 – 46 West North Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- Dr. Logan M. Crichton Residence, built 1896 and demolished before 1959 – 680 Piedmont Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- Grady Hospital Children’s Ward, built 1896-7 and demolished 1959 – North Butler Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Joseph H. Leinkauf Residence, built 1896 – 242 West Peachtree Street, Atlanta (later site of Life of Georgia Tower, Midtown) [Map]

- Apartment house for Harry English, built 1896 – 70-72 Spring Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Jacobs’ Pharmacy, designed in 1896 and demolished in 1930 for the expansion of First National Bank – 6-8 Marietta Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Southern Agricultural Works factory expansion, built in 1896 and destroyed by fire on August 29, 1905 – NW corner of Marietta and Jones Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- William H. Clark Residence, built 1896 – SW corner of East Main Street and Pine Street, Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

- George Washington Scott Residence, “Gulf Haven”, built 1896 – NE corner of Osceola and Pierce Avenues, Clearwater Harbor, Florida [Map]

G.L. Norrman. Elkin & Cooper Sanitorium (1897). Atlanta. - Moore & Marsh Building renovation, existing structure built 1881 and designed byCalvin Fay, renovated according to Norrman’s design in 1897, demolished May 1972 for construction of Woodruff Park – NW corner of Edgewood Avenue and Pryor Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Markham House Company Block, built 1897 and destroyed by fire on February 21, 1901 – 20 Loyd Street [Map]

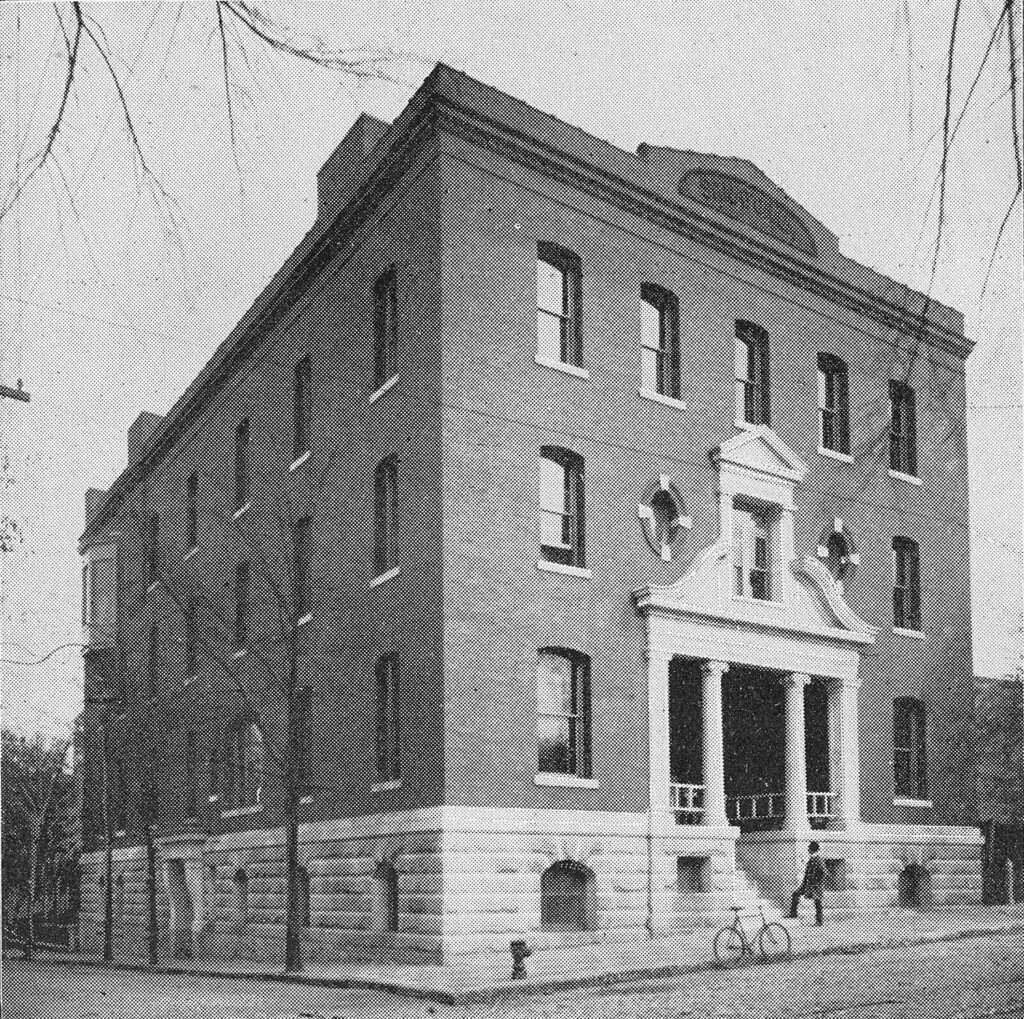

- Elkin & Cooper Sanitorium, built 1897 and demolished circa 1916 for construction of Southern Express Building – 29 Luckie Street, NE corner of Luckie and Fairlie Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Seamen’s Bethel for Savannah Port Society, built 1897 and demolished 1953 – 301-307 East Saint Julian Street, SW corner of East Saint Julian and Lincoln Streets, Savannah [Map]

- Oregon Hotel, built in 1898 and destroyed by fire on March 3, 1912 – Greenwood, South Carolina [Map]

- W.E. Hawkins Residence, built 1898 and destroyed by fire on December 10, 1986 – 635 Piedmont Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- Christian Science Church, built 1898-9 – 17 Baker Street, Atlanta [Map]

- The Fairfax, apartment building for Dr. Hunter P. Cooper, built 1899 and demolished circa 1925 – 220 Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Bertha Rich Residence renovation, completed 1899 – 324 South Pryor Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Eugene R. Black Residence, built 1899 and demolished circa 1930 for construction of a gas station – 893 Peachtree Street, SE corner of Peachtree and 12th Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- James William Thomas Residence, built 1899 and demolished circa 1927 – 568 Spring Street, SW corner of Spring and 5th Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Atlanta Police Barracks, rebuilt in 1899 according to Norrman’s same design from 1892 – Butler Street, Atlanta [Map]

- N.P. Pratt Chemical Laboratory, built 1899 and demolished 1926 – 88-90 Auburn Avenue, NW corner of Auburn Avenue and Courtland Street, Atlanta [Map]

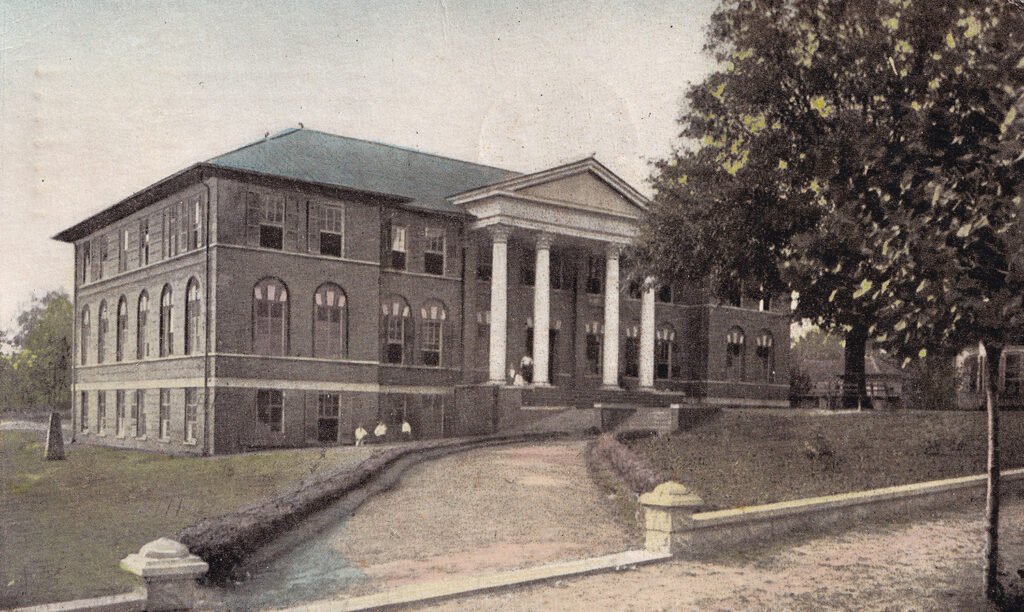

G.L. Norrman. Hardman Sanitorium (1899). Harmony Grove (Commerce), Georgia. - Hardman Sanitorium, built 1899 and demolished after 1960 – 57 North Elm Street, SW corner of North Elm Street and Central Avenue, Commerce, Georgia [Map]

- Bostwick Hall at North Georgia Agricultural College (later University of North Georgia), built 1900 and destroyed by fire on September 25, 1912 – Dahlonega, Georgia [Map]

- Florida Soap Works, built 1900 – Corner of Evergreen Avenue and Eighth Street – Jacksonville, Florida

- S.H. Phelan Residence, built 1900 and demolished circa April 1915 for Phelan Apartments – 790 Peachtree Street, SW corner of Peachtree Street and Peachtree Place, Atlanta [Map]

- Bienville Hotel, built in 1900 and demolished by 1969 – St. Francis and St. Joseph Streets, Mobile, Alabama [Map]

- A.R. Colcord Residence, built 1901 and demolished circa 1949 for the construction of a Sears store – 197 Gordon Street, West End, Atlanta [Map]

- Markham House Company Block, rebuilt 1901 after fire on February 21, 1901 destroyed the previous building designed by Norrman in 1897, demolished circa 1946 for construction of Centra Avenue Viaduct – 20 Loyd Street, Atlanta [Map]

G.L. Norrman. Bisbee Building (1902, left) and West Brothers Building (1902-1970, right). Jacksonville Florida - Leon D. Lewman Residence, built 1901 – 31 Peachtree Place, NW corner of Peachtree Place and Columbia Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- Lewis C. Fletcher Residence, built 1901 – 172 Juniper Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Joseph Van Holt Nash Residence, built 1901 and demolished circa 1946 – 524 Spring Street, NW corner of Spring and 4th Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- John Moreland Speer Residence, built 1901 and demolished after 1975 for a parking lot – 430 South Pryor Street, SE corner of Pryor and Glenn Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Julius Peek business block, built 1901 and demolished circa 1960 for a parking lot – 381-384 Main Street, Cedartown, Georgia [Map]

- West Building, built 1901 and demolished circa 1970 for construction of Independent Life Building – 48-56 West Bay Street, SE corner of West Bay and Laura Streets, Jacksonville, Florida [Map]

- Baldwin Building, built 1901 and demolished circa 1970 for construction of a parking garage – 11-25 West Bay Street, Jacksonville, Florida [Map]

- James L. Munoz Residence, built 1901 and demolished before 1963 – 1101 Riverside Avenue, SW corner of Riverside Avenue and Post Street, Jacksonville, Florida [Map]

- Lawrence Haynes Residence, built 1902 and demolished by 1953 – 399 West Duval Street, NE corner of West Duval and Cedar Streets, Jacksonville, Florida [Map]

- P. Dell Cassidey Residence, built 1902 and demolished September 1937 – 34 West Church Street, Jacksonville, Florida [Map]

- Brady Union Stock Yards, built 1902 and demolished by 1930 – Howell Mill Road, Atlanta [Map]

- Florence Hotel at Brady Union Stock Yards, built 1902 and demolished November 1930 – Howell Mill Road, Atlanta [Map]

- James H. Nunnally Residence, “Woodlawn”, built 1902 and demolished June 1958 for construction of Burke Dowling Adams, Inc. offices – 1470 Peachtree Road, Atlanta [Map]

G.L. Norrman. Graded School (1904). Troy, Alabama. - Milton Dargan Residence, built 1903 and demolished November 1947 – 58 Ponce de Leon Avenue, NW corner of Ponce de Leon and Piedmont Avenues, Atlanta [Map]

- Pierce Hall at Emory College (later Emory University), built in 1903 and demolished in 1961 for the construction of the present Pierce Hall – Oxford, Georgia [Map]

- Citizens Bank, Liberty Street Branch, built 1903 and demolished circa 1965 for a parking lot – NW corner of Liberty and Montgomery Streets, Savannah, Georgia [Map]

- Graded School, built 1903-04 and demolished after 1976 – NW corner of West Walnut and Cherry Streets, Troy, Alabama [Map]

- Harvey M. Smith Residence, built 1904 – 278 West Peachtree Street, SW corner of West Peachtree and West Kimball Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Benjamin H. Abrams Residence, built 1904 and demolished after 1973 – 660 Piedmont Avenue, NW corner of Piedmont Avenue and 5th Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Residential duplex for Christine and Louise Romare, built 1906 and demolished circa 1946 – 487-89 Spring Street, SE corner of Spring and West 3rd Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Office of G.L. Norrman, completed 1906 – Suites 330 and 331, Candler Building, Atlanta

- First Baptist Church, completed 1906 and demolished January 1929 for construction of Regenstein’s store – 209 Peachtree Street, SE corner of Peachtree and Cain Streets, Atlanta [Map]

Norrman & Falkner. James O. Wynn Residence (1908-1958). Atlanta Norrman & Falkner (1906-1908)

- “The Avalon”, apartment building for E.M. Yow, built 1906 and demolished 1929 for construction of a gas station – 249 West Peachtree Street, SE corner of West Peachtree Street and East North Avenue, Atlanta [Map]

- Marion Hotel Annex – built 1907 and destroyed by fire in the Terminal District Conflagration on May 8, 1908 – 55-57 West Mitchell Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Double apartment houses for J.T. Hall, Jr., built 1907 – 25-31 West Baker Street, NE corner of Baker and Spring Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Apartment house for Jennie Golden, built 1907 – 174-178 South Pryor Street, NE corner of South Pryor and Brotherton Streets, Atlanta [Map]

- Dormitory at North Georgia Agricultural College (now University of North Georgia), built 1907 – Dahlonega, Georgia

- Trinity Methodist Church Annex/Atlanta Boys’ Club building, renovation and expansion of former parsonage completed 1907 and demolished December 1912 – SW corner of Whitehall Street and Trinity Avenue, Downtown [Map]

- W.M. McKenzie Residence at “Brookwood”, former property of Joseph P. Thompson, built 1908, Atlanta

- Commercial building for David Woodward, built 1908 and demolished after 1971 – 262-268 Peters Street, SE corner of Peters Street and Curtis Alley, Atlanta [Map]

- James O. Wynn Residence, built 1908 and demolished circa 1958 – 1126 Peachtree Street, Atlanta [Map]

- Henry E. Harman Residence, “Mildorella”, built 1909-10 and demolished after 1926 (plans credited to Norrman & Falkner) – Likely located south of Glenwood Avenue opposite East Lake Golf Club, East Lake, Atlanta

G.L. Norrman

- John Slaughter Candler Residence, built 1909 and demolished September 1952 for construction of Druid Hills Methodist Church – 850 Ponce de Leon Avenue, NE corner of Ponce de Leon and Moreland Avenues, Atlanta

Norrman, Hentz & Reid (1909-10)

- A.G. Rembert Residence, built 1909 – 267 North Church Street, SE corner of North Church and East Charles Streets, Spartanburg, South Carolina [Map]

G.L. Norrman (attributed). C.E. Fleming House. Spartanburg, South Carolina. Lost Works Attributed to G.L. Norrman

- Mrs. E. E. Evins Residence, built 1879 – North Liberty Street, Spartanburg, South Carolina. The January 7, 1880, issue of The Spartanburg Herald described this and 2 other recently completed homes as “three of the nicest residences in town”, adding that “They do credit to the architect who drew the plans.” As Norrman was the only architect in Spartanburg at that time, the home was likely of his design. [Map]

- Mr. Holtzclaw Residence, built 1879 – North Liberty Street, Spartanburg, South Carolina. The January 7, 1880, issue of The Spartanburg Herald described this and 2 other recently completed homes as “three of the nicest residences in town”, adding that “They do credit to the architect who drew the plans.” As Norrman was the only architect in Spartanburg at that time, the home was likely of his design. [Map]

- W.I. Harris Residence, built 1879 – North Liberty Street, Spartanburg, South Carolina. The January 7, 1880, issue of The Spartanburg Herald described this and 2 other recently completed homes as “three of the nicest residences in town”, adding that “They do credit to the architect who drew the plans.” As Norrman was the only architect in Spartanburg at that time, the home was likely of his design. [Map]

G.L. Norrman (attributed). Jesse Cleveland House (1882-1938). Spartanburg, South Carolina. - Dr. Jesse Cleveland Residence, built in 1882 and demolished in November 1938 for the construction of Cleveland Junior High School – SW corner of Howard and Franklin Streets, Spartanburg, South Carolina. Jesse Cleveland and his brother, John B. Cleveland, built identical Second Empire-style homes in the 1880s, with the first built by Jesse Cleveland in 1882. Although unconfirmed, the plan for both homes was likely designed by Norrman, based on a strong similarity to the architect’s other works at the time, including Stone Hall in Atlanta, also built in 1882. As additional evidence of Norrman’s involvement, an article in the April 29, 1990, issue of the Spartanburg Herald-Journal stated that the architect of Bon Haven also designed the Cleveland Law Range in Spartanburg — Norrman was almost certainly the designer of that building. [Map]

- John B. Cleveland Residence, “Bon Haven”, built 1884 and demolished September 2017 – Church Street, Spartanburg, South Carolina. A duplicate of the earlier home designed for Jesse Cleveland, the home was given an extensive renovation and Neoclassical-style overlay circa 1920. After many years of abandonment, the home was demolished by the Cleveland family in September 2017, despite extensive public efforts to spare the structure. [Map]

- C.E. Fleming Residence, built before 1884 – Main Street, Spartanburg, South Carolina. Based on photographs of this residence, its design can be easily attributed to Norrman, based on its similarity to his other home designs in the late 1870s and early 1880s.

- Albert H. Twichell Residence, built in 1882 and demolished in 1979 – 235 South Pine Street, Spartanburg, South Carolina. With a prominent central tower and 2-story porch on the front elevation, this rambling Queen Anne-style home appears to have been the forerunner of numerous residential designs by Norrman in the 1880s and 90s, including the T.A. Latham House in Atlanta and the R.O. Barksdale House in Washington, Georgia. [Map]

G.L. Norrman (attributed). T.B. Neal Residence (1887). Atlanta. - T.B. Neal Residence, built 1887 and likely demolished for construction of East-West Expressway (I-20) – 78 Washington Street, SE corner of Washington and Fair Streets, Atlanta. A photograph of this home reveals a strong resemblance to several of Norrman’s residential designs of the 1880s, including the Edward C. Peters House in Atlanta and the George A. Noble House in Anniston, Alabama. [Map]

- Thomas Sumner Lewis Residence, built circa 1889 and destroyed by fire on May 21, 1917 – 246 North Jackson Street, Atlanta. This home can be easily attributed to Norrman based on its characteristic massing and distinct resemblance to other works by the architect; the structure appears to have been destroyed in the Great Atlanta Fire of 1917. [Map]

- Andrew P. Thompson Residence, built 1889 and demolished circa 1910 – 76 North Spring Street, Atlanta. The building permit for this home was issued in August 1889, and while its designer is not officially known, based on an aerial photograph of Atlanta circa 1895, the structure appeared very similar to other Norrman homes from the time, and included the distinctive round tower the architect incorporated in designs such as the W.W Duncan House in Spartanburg, South Carolina; and the E.B. Hawkins House and Windsor Hotel in Americus, Georgia. [Map]

- John S. Paden Residence, built in 1891 and demolished in the 1960s – 906 Forrest Avenue, SW corner of Forrest Avenue and 9th Street, Gadsden, Alabama. This handsome Colonial Revival-style home was likely one of 2 houses Norrman reportedly designed in Gadsden circa 1890. [Additional image] [Map]

- T.S. Kyle Residence, building date unknown and demolished in the 1960s – 834 Forrest Avenue, SE corner of Forrest Avenue and 9th Street, Gadsden, Alabama. Built across the street from the John S. Paden House, this Queen Anne-style home was likely one of 2 houses Norrman reportedly designed in Gadsden circa 1890. [Additional image] [Map]

G.L. Norrman (attributed). Dexter E. Converse Residence (1891), Spartanburg, South Carolina. - Dexter E. Converse Residence, completed March 1891. This elaborate Queen Anne-style home included several distinctive features of a Norrman design. Converse was also the brother-in-law of A.H. Twichell, likely a former client of Norrman’s.

- Max Kutz Residence, built 1892 and demolished circa 1958 – 245 Washington Street, Atlanta. This home was built for a leading Jewish merchant who also served on the board of directors for the Hebrew Orphans’ Home, which Norrman designed. Despite its unusual Gothic inspiration, the striking residence had the unmistakable massing of a Norrman design. The home was demolished for the construction of the 106-acre Capitol Avenue Interchange (now I-75/85/20 Interchange). [Map]

- Commercial building for East Atlanta Land Company, built 1892 and demolished 1939 – 161-165 Edgewood Avenue, SW corner of Edgewood Avenue and Piedmont Avenue, Atlanta. This was one of at least 3 speculative commercial buildings constructed by the East Atlanta Land Company along Edgewood Avenue — Norrman was the confirmed designer for one (Exchange Building), and likely designed the other two, based on their similarity to his other works from the time. First occupied by the Klouse & Cheny Meat Market, this 3-story building was demolished for the construction of Hurt Park. [Map]

G.L. Norrman (attributed). Benjamin H. Wilson Residence (1892-1952). Spartanburg, South Carolina. - Benjamin H. Wilson Residence, built 1892 and demolished 1952 – 570 East Main Street, NW corner of East Main Street and North Fairview Avenue, Spartanburg, South Carolina. This home was built for B.H. Wilson — the president of Converse College — on land that adjoined the college property. The home’s massing and Moorish-inspired design clearly indicate Norrman’s involvement. The home was later owned for many years by J.H. Sloan, a local industrialist. [Map]

- Benjamin F. Abbott Residence, built 1892 — Peachtree Road, Atlanta. In October 1891, Abbott sold his existing home on Peachtree Street — designed by Norrman in 1884 — to Dr. W.S. Elkin, who would later become a client of Norrman’s. Abbott built a new “country home” in the English View area of Peachtree Road, close to the Joseph P. Thompson House, also designed by Norrman. The second Abbott home was completed in September 1891, and a photograph of the structure suggests that Norrman was likely its designer.

- U.S. Army Headquarters, Atlanta. 1904 alteration to Leyden House, built in 1858 and designed by John Beutell – 124 Peachtree Street, Atlanta. This landmark 2-story Greek Revival mansion was built for H.H. Tarver in 1858 and notably served as the Union Army’s headquarters during its occupation of Atlanta in 1864. The structure was converted into a boarding house in the 1870s and was substantially rebuilt after being gutted by fire in February 1885. Norrman himself rented a room in the home circa 1894-95. The December 25, 1903, issue of The Atlanta Constitution reported that Willis R. Biggers, “with J.R. Norman, architect”, was in charge of renovating and expanding the home for its temporary use by the United States Army’s Department of the Gulf. Biggers had worked as a draughtsman for Norrman in 1893 and 1894 and was employed by multiple Atlanta architects before establishing a solo career in the 20th century. Assuming “J.R. Norman” refers to G.L. Norrman, it appears Biggers was once again working for Norrman circa 1903-04. The renovation of the Leyden House included the conversion of the front rooms to offices, the addition of a private bathroom in each bedroom, carpeting, tiling, and painting. The renovation was completed in January 1904, and the Department of the Gulf occupied the building until February 1906. The home was demolished in 1914. [Map]

G.L. Norrman. Dougherty County Courthouse (1892, unbuilt). Albany, Georgia. Unbuilt Projects by G.L. Norrman

- First Presbyterian Church in Anderson, South Carolina. Norrman submitted plans for a sanctuary as described in a letter dated July 12, 1878, sent from Norrman to W.W. Humphreys of the church’s building committee. The completed project was built from 1879 to 1882 and designed by “Architect Russell” of Charleston, South Carolina, and Jeptha F. Wilson of Anderson.

- Watkins Institute in Nashville, Tennessee. Norrman & Weed was one of six architectural firms that submitted plans on October 6, 1881, for an educational facility including a library and lecture hall. The contract was awarded to Bruce & Morgan of Atlanta. A.C. Bruce (with T.H. Morgan as his draftsman) had originally practiced in Nashville, and the pair designed several works in that region.

- Jack W. Johnson Residence in Atlanta. The March 1, 1882, issue of The Atlanta Constitution reported that Humphries & Norrman were designing a home for Jack Johnson, which it predicted would be “the tastiest building on Peachtree street”. It appears the home was never built, as Johnson continued living in hotels and apartment houses before moving to Birmingham, Alabama, in 1887. In March 1883, Johnson bought a lot on the “upper end of Peachtree” next to William Dickson and Willis Ragan, with the stated intention of building a residence. Dickson and Ragan both began building homes designed by Norrman, but Johnson sold his lot to Ragan in August 1883.

- Lewis Beck Residence in Atlanta. The Atlanta Constitution reported in April and May 1882 that Humphries & Norrman were planning a home for Lewis Beck, following his purchase of half of the W.H. Venable lot on Peachtree Street. Beck apparently never built the home and continued his residence for many years in the Kimball House Hotel.

- Julius Brown Residence in Atlanta. Norrman was originally hired to design this home, but after he and Brown violently feuded, Bruce & Morgan of Atlanta took over the project. Brown later falsely claimed sole credit for the home’s design.

- Chamber of Commerce Building in Atlanta. An open competition was held in 1883, with designs submitted by Humphries & Norrman, Bruce & Morgan, E.G. Lind of Atlanta, and Fay & Eichberg of Atlanta. The winning proposal was designed by Fay & Eichberg.

- Swift Specific Company in Atlanta. The June 10, 1883, issue of The Atlanta Constitution reported that plans were ordered from Humphries & Norrman for a $12,000 factory building for this company. The October 20, 1883, issue of The American Architect and Building News reported that E.G. Lind was the architect for the completed project, which Lind’s own records also verify.

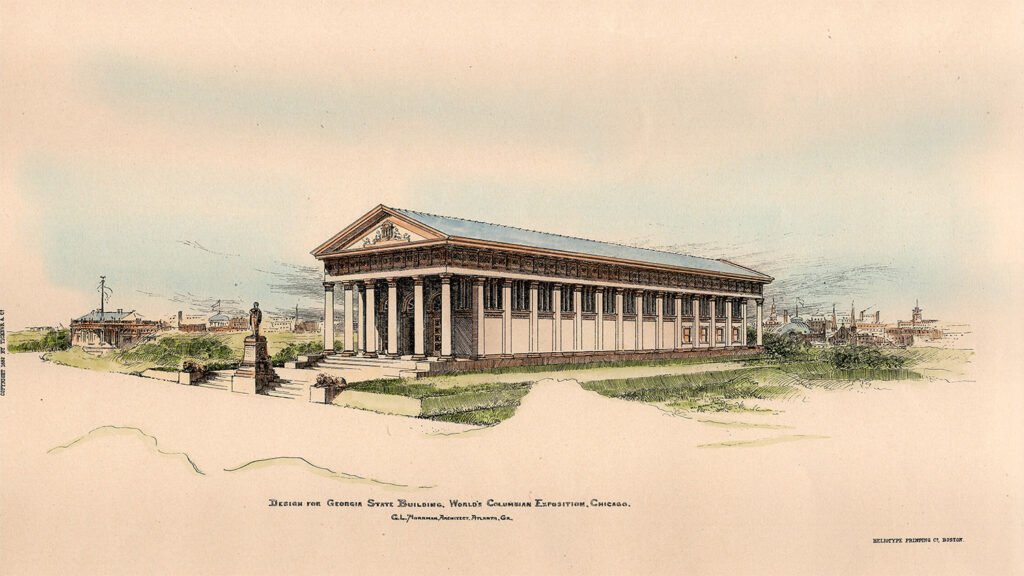

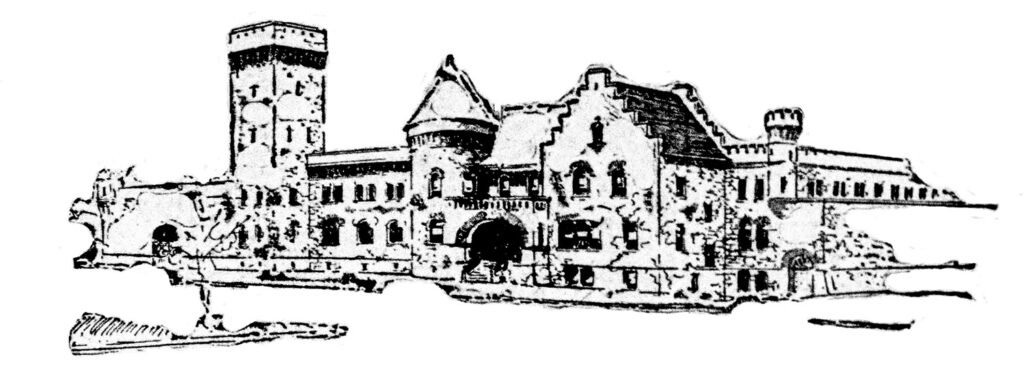

- Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta. Humphries & Norrman was one of 9 firms that submitted plans for the state capitol building in January 1884. Following a contentious examination process, the building committee narrowed down their selection to just 3 designs, one of which was Norrman’s. The committee asked George B. Post, an architect of New York, to examine the 3 plans. Post dismissed Norrman’s plan as “very picturesque” and favored the design by Chicago’s Edbrooke & Burnham, who were awarded the project in February 1884.

- Chatham County Jail in Savannah, Georgia. The October 2, 1885, issue of Savannah Morning News reported that Norrman and E.G. Lind — using the name Lind & Norrman — submitted plans for a county jail in an open competition. Based on this project’s absence from Lind’s personal records, it appears that Norrman was the designer, and this may have been an attempt to form a partnership between the 2 architects after the dissolution of Humphries & Norrman. Thirteen plans were submitted in the competition, and on January 13, 1886, McDonald Brothers of Louisville, Kentucky, were selected to design the jail. Norrman and Lind did not enter into a partnership.

- Five stores in Atlanta, circa 1885. The November 22, 1887, issue of The Atlanta Constitution published a quote from Norrman claiming that he “had some drawings made for five stores, two years ago, but they were not built, as the owner did not think it would pay to build them after prohibition started”.

- $40,000 business block in Gadsden, Alabama. The March 8, 1888, issue of The Gadsden Weekly Times and News reported that Norrman bought a lot for $1500 at the corner of Locust and 4th Streets in Gadsden — across from the Printup Hotel — with the intent of building a block of businesses on the property. This report was further confirmed in the March 21, 1888, issue of The American Engineer. Based on Sanborn maps, the project was never executed.

- Renovation and expansion of Screven House Hotel in Savannah, Georgia. The December 8, 1888, issue of The Morning News reported that Norrman was drawing plans for a $100,000 renovation and expansion of the Screven House Hotel, which opened in 1854 and was enlarged in 1857 and 1860. The hotel was located on the southeast corner of Congress and Bull Streets at Johnson Square. With a planned start date of May 1, 1889, the expansion project designed by Norrman does not appear to have been executed, and the entire complex was demolished in 1923.