Category: Architecture

-

The Overline (2023) – Atlanta

Morris Adjmi Architects. The Overline (2023). Old Fourth Ward, Atlanta.1 -

“Light in the Schools” (1893) by W.W. Goodrich

W.W. Goodrich. Cornice and capital on Yonah Hall (1893). Brenau University, Gainesville, Georgia. The Background

The following article was published in The Atlanta Journal in 1893, and written by W.W. Goodrich, an architect who practiced in Atlanta between 1889 and 1895.

If Goodrich ever designed a classroom building during his time in Atlanta, there’s no record of it. His only known project for an educational institution in the Southeast is Yonah Hall, a dormitory and library at the Georgia Female Seminary1 2 3(later Brenau University) in Gainesville, Georgia.

Goodrich also wasn’t an ophthalmologist, but that didn’t stop him from attempting to diagnose the cause of myopia and astigmatism in Atlanta’s children.

“Atlanta today is inquiring the cause of its youth wearing glasses,” Goodrich writes. Were they, though? “Little boys and girls in our city are seen every day wearing glasses”, he continues, adding, “In the times of our grandparents, children wearing glasses were unknown and unheard of.”

Citing “European oculists”, here Goodrich attributes vision problems in Atlanta’s students to a lack of northern light in their classrooms, and then provides a detailed description of an ideal school building of the early 1890s: built on a ridge, designed with a steel frame and fireproof materials (requiring “no insurance”, apparently), with a north light in the classrooms — “and only a north light”, he stresses.

I won’t criticize Goodrich’s description too much — it’s more interesting than most of the things he wrote about. It’s also true that schools at the time were often designed so that their classrooms were primarily exposed to the softer, consistent tones of northern light, but that wasn’t always practicable due to site limitations.

Note that Goodrich’s plan includes a “dynamo” to “furnish the light for dark days” — electric lighting was available, but was quite dim by modern standards, so architects still had to design schoolrooms to receive as much natural light as possible.

In the 1880s and early 1890s, Bruce & Morgan of Atlanta were the indisputed leaders of school design in the Southeast, planning so many academic structures that in 1889, they even wrote a book about it: Modern School Buildings, which included full-page illustrations of their projects.4 If a copy of the book still exists, I’m unaware of it.

Of the dozens of grade schools designed by Bruce & Morgan, only one remains in Union, South Carolina.5 However, most of their landmark college buildings still stand, such as the Main Building at Georgia Tech in Atlanta, Samford Hall at Auburn University in Alabama, and Agnes Scott Hall at Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia. Only the buildings at Auburn University and Agnes Scott College are north-facing, but all of the firm’s school designs feature an abundance of oversized windows.

In 1891, G.L. Norrman addressed the problem of school lighting with his plan for Atlanta’s Edgewood Avenue Grammar School. Built on a ridge with a north-facing front, the building was designed so that each of the 8 classrooms received sunlight from four sides, and as the Atlanta Journal reported of the plans: “Mr. Norrmann [sic] himself is so much in love with them that he has had them copyrighted.” He immediately repeated the Edgewood plan for theSixteenth Street School in Columbus, Georgia, and both buildings survive.

In 1896, Norrman’s plan for the Anderson Street School in Savannah, Georgia, was reportedly selected, in large part, because all 12 of its classrooms received southern exposure.6 So much for that theory on northern light. The Anderson school plan was so successful that Norrman later duplicated it for both the 38th Street School and Barnard Street School in Savannah — all 3 buildings still exist.

Goodrich praises his fellow Atlanta architects in this article, describing them as “men of rare discernment and practical intelligence” and commending their “beautiful school buildings”. Obviously, Goodrich was a bullshitter and ass-kisser, but he was right about one thing: Atlanta’s architects did design some beautiful school buildings.

Light In The Schools.

A Suggestion For The Board Of Education.

The North Light Only Should Be Used.

Mr. W.W. Goodrich Calls Attention to the Matter.

What the European Governments are Doing for Protection and the Good Results Obtained.

Written for The Journal.

The public is at present more interested in schoolhouse sanitation, and the light in our public school rooms than in any other subject before our practical, everyday people, who have made Atlanta what she is and what she will be “in the glorious future.”

Atlanta today is inquiring the cause of its youth wearing glasses. Myopic and astigmatic optics are of such frequent occurrence and of such everyday appearance on the streets that people have ceased to wonder at its cause or causes, and accept the fact as a matter of course, and pass the subject by as too frivolous to be thought of, or of too common place a subject to pay any attention to.

The optic organism is of such a sensitive nature, and its development of such a wonderful use to everyone, that without good eyes anyone thus afflicted is indeed in a sad predicament. And yet, little boys and girls in our city are seen every day wearing glasses. In the times of our grandparents, children wearing glasses were unknown and unheard of.

The subject being discussed must and should be first thought of your public school board, “yet that august body,” so far as the parents of the school children are aware, have never considered this subject at all. At least if they have, the school-room does not show it, and the astigmatic and myopic optics of many pupils are in contradistinction to good sanitary school measures and good optical schoolroom arrangements.

“First”–A site for a schoolhouse should be on a ridge, so that the drainage shall fall on all sides.

“Second,” the site should be a north light, and a north light only; each room should have a north light, and only a north light, and no other light from any other points of the compass, should enter a schoolroom than what comes from a direct line to the north star.

“European oculists” have convinced their respective governments that to preserve the eyes of the present and future generations, only a north light will be admitted in a school room and in all class rooms whether in public or private room, and the governments of Europe have made laws to that effect. The effect of said laws has been to decrease optical diseases or malformations, to cure many old and chronic cases in children and to increase and restore the mental and physical health of all its youth, and to eradicate occult faults. Truly a wonderful blessing, more so than vaccination for smallpox. It is thus seen, that it is imperative upon the school board, to first consider that subject treated. And not let it go by without any consideration.

Atlanta has beautiful school buildings, the architects of them are men of rare discernment and practical intelligence, graceful, classic detail, and ornament, that thrill the mind’s eye, and enrapture the soul, and inspire the whole being to do grand and great things for our city, rise uppermost in the pupil and student of both sexes.

And they have a keener discernment to accomplish great tasks and to improve their minds by their study under the classic roofs and Roman detail and Spartan simplicity than is accomplished under any other order of architecture.

Structural construction should be a thoroughly ventilated basement built of granite, cased with hollow tile, and plastered with the patent wall coverings inside.

The superstructure, of pressed brick, terra cotta and marble trimmings, lined with hollow tile, plastered with patent wall coverings on the inside.

The floor joists and studding of steel filled in with hollow tile, the studding plastered with patent wall covering in a light tint of bluish gray, the ceilings of pearl green.

The floor covered with asphaltum over the hollow tile; “no wood at all” on the floors.

The roof of steel, covered with slate. The windows should have plate glass, so that there will be no reflex curves and no distorted concave or convex surfaces.

The sanitary arrangements should be in an annex and of the most scientific appliances with ventilating shafts. The ventilation should be by a fan and air shafts, a dynamo run by city service easily kept in order, constantly in motion, would change the air in each room in three minutes, and the dynamo could furnish the light for dark days, or for scientific laboratory work.

The building entire heated by live steam, using direct in a coil in tanks in the basement for each room service, and conveyed upward by fan.

It will be seen at a glance that our building is “fire proof”–no insurance, no nuisance by defective plumbing, and solid as the future of Atlanta. Her educated and practical architects can blend the requirements of hygiene with that nobles of all professions “American Architecture,” and Atlanta must be as she should be, the center from our which shall go the saying that she sets the face of the world.

W.W. GOODRICH7

References

- “A Great School for Gainesville.” The Atlanta Constitution, May 25, 1893, p. 3. ↩︎

- “An Elegant Building.” The Atlanta Journal, June 22, 1893, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Gainesville Gossip.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 23, 1893, p. 3. ↩︎

- “From Our Notebook.” The Atlanta Constitution, June 23, 1889, p. 17. ↩︎

- “The Graded School Building.” The Weekly Union Times (Union, South Carolina), June 19, 1891, p. 2. ↩︎

- “The New School Building.” The Morning News (Savannah, Georgia), February 12, 1896, p. 8. ↩︎

- Goodrich, W.W. “Light In The Schools.” The Atlanta Journal, April 17, 1893, p. 3. ↩︎

-

First Union National Bank (1971) – Greensboro, North Carolina

-

UNC Charlotte Center City (2011) – Charlotte, North Carolina

KieranTimberlake. UNC Charlotte Center City (2011). Charlotte, North Carolina. 1 References

-

High Museum of Art (1983) – Atlanta

Richard Meier. High Museum of Art (1983). Atlanta.1 In foreground: Roy Lichtenstein. House III (1997).2 References

- “A New High”. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, October 9, 1983, Section M. ↩︎

- House IIII – High Museum of Art ↩︎

-

“Hints on Hygiene” (1893) by W.W. Goodrich

The Background

The following article was published in The Atlanta Journal in 1893, and written by W.W. Goodrich, an architect who practiced in Atlanta between 1889 and 1895.

Like any self-respecting architect, Goodrich considered himself an expert on, well, just about everything. Here, he pontificates on the health and dietary habits of 19th-century Americans in a condescending and frequently offensive diatribe that begins by dismissing vegetarians as “fanatics” while also scolding “the rich” for “the excessive use of meats.”

Sounding every bit like a shill for the dairy industry, Goodrich spends the bulk of the article extolling the alleged benefits of drinking milk, with a string of dubious assertions unsupported by modern science. Everything from fever to liver failure could be cured with a “milk regimen” he explains, as practiced by “certain savage or semi-civilized tribes of pastoral habits.”

Goodrich made these claims at a time when milk production was unregulated in the United States, and dairy manufacturers regularly tainted their products by dumping in everything from calf brains to formaldehyde, leading to the outbreak of multiple diseases and the poisoning deaths of thousands of Americans — primarily infants. Drink up!

As Goodrich acknowledges, tuberculosis was frequently transmitted by bacteria found in unboiled milk, a danger well known to the public by the 1890s. Here, he advocates for the pasteurization of milk, a process that was not widely employed in the United States at the time, and would not be legally required until the early 20th century.

Goodrich’s stated desire in this writing was “to infuse a little hygienic good sense into the average American” who only needed to “observe the laws of temperance.”

And as for the people of Atlanta? “Nowhere in the world is self-restraint more necessary than in Georgia”, he explains, claiming that the hot and humid climate of the Southeast both “stimulates the appetite” and “render[s] digestion difficult”.

Why ask a doctor for health advice when you can consult a third-rate architect?

Hints on Hygiene

Some Secrets of Good Health for Every Day Use by Everybody.

Written for the Journal.

If people knew how to eat and drink properly or were willing to confine themselves to articles of food suited to their digestion, and would just take the amount of exercise necessary to facilitate the digestion, the lives of the greater part of the human race would be indefinitely prolonged.

There would have to be excepted from this sweeping assertion certain diseases – like those of throat and lungs – that cannot always be avoided, but which nevertheless in many cases can be limited in their ravages by prudence.

The statement as made is a truism, and has been known to sensible persons since dawn of civilization and the origin of gormands and epicures. Some old Persian writer placed the whole secret of health in the ability to leave off eating before the appetite was entirely satisfied, and the wise men of Greece and Rome never ceased to preach similar truths, both by precept and example. These things they had learned, not from works on hygiene, which did not abound in ancient times, nor from family physicians, who were far from being plentiful as they are now but from simple observation.

The apostles of a vegetable diet have usually been fanatics, but there has always been a grain of truth in their doctrines, for it is true that the greater part of diseases are caused, especially among the rich, by the excessive use of meats.

It is only a few years since the nourishing qualities of milk and its hygienic value began to be properly appreciated. Everyone was aware that the young of the human race and of the lower animals using it as their only diet flourished and grew strong alike in bone and muscle.

It appeared to be easily digested and seemed to contain all the elements that the body seemed to need, at least in the early stages of its growth. Adults – at least those in civilized countries – despised it and would have considered themselves doomed to an early death had they found themselves confined to a milk regimen. The same opinion, has, fortunately, not prevailed among certain savage or semi-civilized tribes of pastoral habits, who have maintained a healthy existence from time immemorial on milk and its products.

Medical science, aided by chemistry, has for some years past been working a gradual change in these ancient prejudices.

The chemists have discovered that milk contains all the elements necessary to make blood, bone and muscle. It adapts itself to the most difficult digestion.

A man can live and enjoy perfect health on milk and its products alone, or his system find in it everything needful – fatty matter, caseine, albumen, and especially phosphate of lime for building up his bony framework. Doctors prescribe it for patient suffering from low fevers.

If a person finds himself suffering from torpididty of the liver, or a tendency to indigestion let him drink milk freely, say two or three quarts a day, and abstain from meat, and he will almost invariably find himself cured speedily.

It may be said of certain diseases of the liver and kidneys and of the dyspepsia that they have invariably been brought on by ignorance or disregard of the laws of hygiene, and no one need ever have them unless he is obliged to live in the tropics, or has by chance been so situated that the choice of his diet was beyond his control.

It has been in all ages of the world been difficult to make any considerable number of human beings observe the laws of temperance in eating and drinking if the means of indulgence were at their disposal.

It is much more difficult to infuse a little hygienic good sense into the average American of today than into the luxurious Roman in the time of Lucullus, and nowhere in the world is self-restraint more necessary than in Georgia, where the climate constantly stimulates the appetite, while at the same time certain latent qualities of the atmosphere seem to render digestion difficult.

While milk in its perfect state is capable of such infinite service to the health, it has at the same time an extraordinary facility in transmitting diseases. A great part of that consumed in large cities is from cows kept in stables and fed often on unwholesome food.

When tuberculosis diseases become too common among these animals the newspapers ventilate the matter and the health officers show a temporary activity, but the evil continues. It is more trying from the fact that diseased milk is largely used as nourishment for young children.

If the purity of milk is suspected, however, it only needs to be remembered that the noxious germs it contains may be destroyed by boiling. In England, where milk is rarely boiled, there have been occasional local epidemics caused by the use of milk from diseased cows.

In 1870 an epidemic of typhoid fever at Islington was propagated in this manner. Epidemics of croup and scarlatina have also in England been attributed to the same cause. The nutritive and hygienic qualities of milk and its tendency to transmit disease have for the last ten years been frequent subjects for discussion at the sessions of the Paris Academy of Medicine. The matter is sufficiently practical and important to attract the attention a little oftener of medical associations in America.

W.W. Goodrich1

References

- Goodrich, W.W. “Hints on Hygiene.” The Atlanta Journal, April 29, 1893, p. 1. ↩︎

-

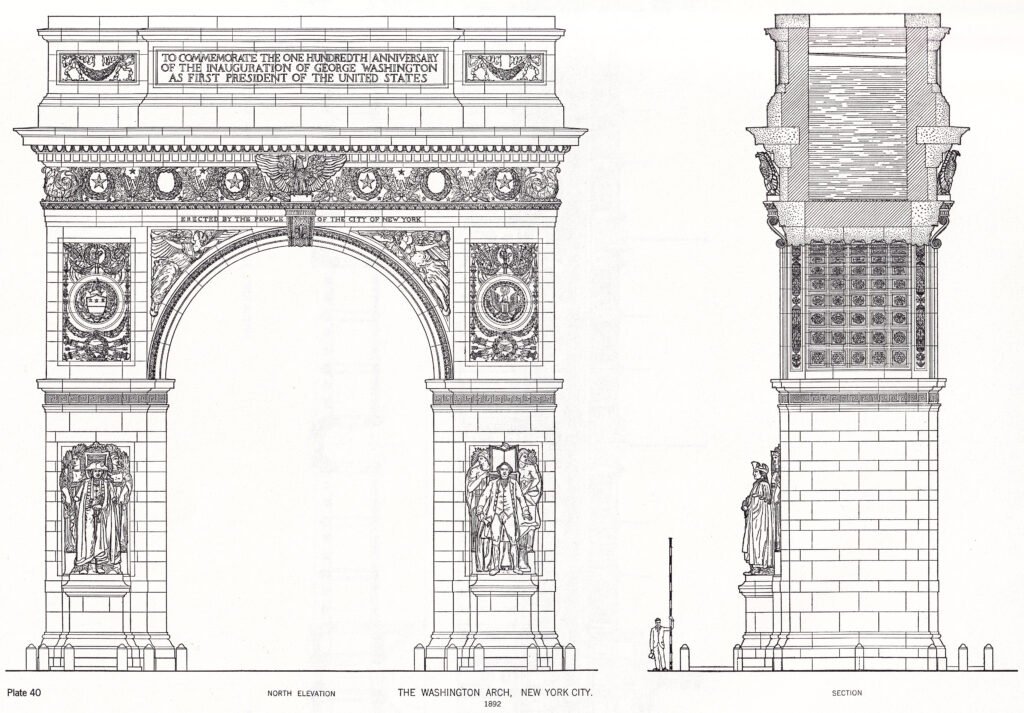

Washington Square Arch (1891) – New York

Stanford White of McKim, Mead & White. Washington Square Arch (1892). Greenwich Village, New York.1 Elevation and Section2

References

- “The Last Stone Is Laid.” The World (New York), April 6, 1892, p. 10. ↩︎

- A Monograph of the Work of McKim Mead & White, 1879-1915. New York: The Architectural Book Publishing Company, 1915. ↩︎

-

“Atlanta’s Advancement” (1893) by W.W. Goodrich

Charlie Mitchell.Everyday MARTA Scenes (1982). Arts Center Station, Atlanta.1 The Background

The following article was published in the The Atlanta Journal in 1893 and written by W.W. Goodrich, an architect who practiced in Atlanta between 1889 and 1895.

Atlanta has long been a mediocre city gagging on its own arrogance and self-importance, a characteristic that can be definitively traced to the 1880s, when Henry W. Grady turned the Atlanta Constitution into a daily mythmaking machine of endless puff pieces that touted the city in near-religious terms as the predestined savior of a resurrected “New South” that would soon rival the industrial centers of the North.

So effective was the propaganda that to this day, deluded Atlantans — despite all evidence to the contrary — will avow that Atlanta is a “world-class city” poised to overtake New York, Los Angeles, or [insert city name here] at any moment. That moment, of course, never arrives.

Here, Goodrich followed the template of hundreds of other gushing Atlanta promotional articles in the 1890s, starting with the subtle proclamation: “Atlanta is a phenomenal city.” He goes on to praise the city’s “master minds”, “great and grand monuments”, “charming homes” and “genuine” architects, concluding that Atlanta’s destiny was to be — wait for it — “the Chicago of the south”.

This is an article stuffed with so many lies and embellishments that it can only be considered a humorous work of fiction, and Goodrich repeats many of the sentiments he expressed in his similar 1892 article, “Atlanta’s Unique, Composite and Attractive Architecture”.

Goodrich no doubt hoped that stroking Atlantans’ egos would drum up business for himself: at the time of this article’s publication, the United States was in the throes of the Panic of 1893, which plunged the nation into an economic depression for over 4 years.

Most Atlanta architects struggled greatly at that time, and many left the city altogether, including Goodrich, who in 1893 was already dividing his time between Atlanta and Norfolk, Virginia.2 3 Goodrich’s company still claimed some presence in the city in December 1894,4 but his final Atlanta newspaper advertisement was in February 1895.5 I doubt he was greatly missed.

Atlanta’s Advancement

Her Growth In Architecture Discussed.

W.W. Goodrich Writes Interestingly.

On the Beauties of the Homes of Atlanta.

The Center of the Best Field for Building Materials in the Country – Artistic Home Adornment.Atlanta is a phenomenal city. The wonderful recuperative powers inherent in the master minds of this progressive city, has stood it many good turns in the past, and is at the front today, crowding out the pessimists, supplanting them and their narrow views, and erecting upon their small ideas great and grand monuments to a future as well as to this present generation.

Beautiful homes, are all about, practical contentment assures that observer on every hand “that life is worth living,” and that Atlanta’s homes are models of rare elegance, bliss, “and homes, sweet home.”

The best building materials to be had in the “known world” are all native to Georgia, the empire state of the south, and are all within a radius of fifty miles of Atlanta. These materials are to be seen everywhere “in this city of charming homes.” And none is too humble but that some one or more of Georgia’s native building materials are in its make-up and form an integral part of the harmonious whole of Atlanta’s homes, that are known far and wide as being the best and most carefully studied and constructed; and arranged in their entirety, more so than in any other city of our common country.

The diversified forms of architecture are here blended.

The many inventions for good health and labor saving appliances for the housewife are in every home.

It is the progressive study of Atlanta’s architects. And many of them are educated, practical men, thoroughly versed in its many intricate ramifications to design for their clientele only that which will be an additional ornament to Atlanta’s excellent structural monuments, that so attract our northern and western friends, and they go from us to their own homes, with the most pleasing reminders of the hospitality of our southland, that each genuine architect, each real lover of his profession, who is so thoroughly imbued with his chosen calling banishes all other thoughts from his mind, and with his brother professional urges the many clients to use only native Georgia products, native Georgia labor, home industry and home labor, and thus imbued we have a style of architecture that is gradually being woven from the warp and woof of the past and present into a beautiful architectural mantle that so handsomely adorns Atlanta and her progress. Atlanta is thus garmented on every hand. The cottage homes of Atlanta and her beautiful suburbs are her pride. The thrift of a city is in its suburban population, because any city without suburbs is a dead, non-progressive affair, not worthy to be called even a village. The many suburbs are taking on metropolitan airs. Electrical lines are running and being planned to run everywhere.

The sound of the hammer and the merry whiz of the saw erect the ear, all denoting progress, thrift and sturdy belief in the greatness of our claim that Atlanta is the magic city of the south, and that her destiny is to be, and will be, the Chicago of the south. With this belief each one of her thousands stand shoulder to shoulder – a steady, solid phalanx of veterans ready to battle for Atlanta’s future, Atlanta’s greatness and Atlanta’s grandeur.

W.W. Goodrich6

References

- MARTA’s Art Program – MARTA ↩︎

- “W.W. Goodrich & Co., Architects” (advertisement). Norfolk Virginian (Norfolk, Virginia), August 17, 1892, p. 2. ↩︎

- “The Passing Throng.” The Atlanta Constitution, January 8, 1893, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Bright Days Ahead”. The Atlanta Constitution, December 27, 1894, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Professional Cards.” The Atlanta Constitution, February 27, 1895, p. 7. ↩︎

- Goodrich, W.W. “Atlanta’s Advancement”. The Atlanta Journal, March 25, 1893, p. 1. ↩︎

-

Marcus Tower, Piedmont Hospital (2020) – Atlanta

HKS Architects. Marcus Tower, Piedmont Atlanta Hospital (2020). Buckhead, Atlanta.1 References

-

“Atlanta’s Unique, Composite and Attractive Architecture” (1892) by W.W. Goodrich

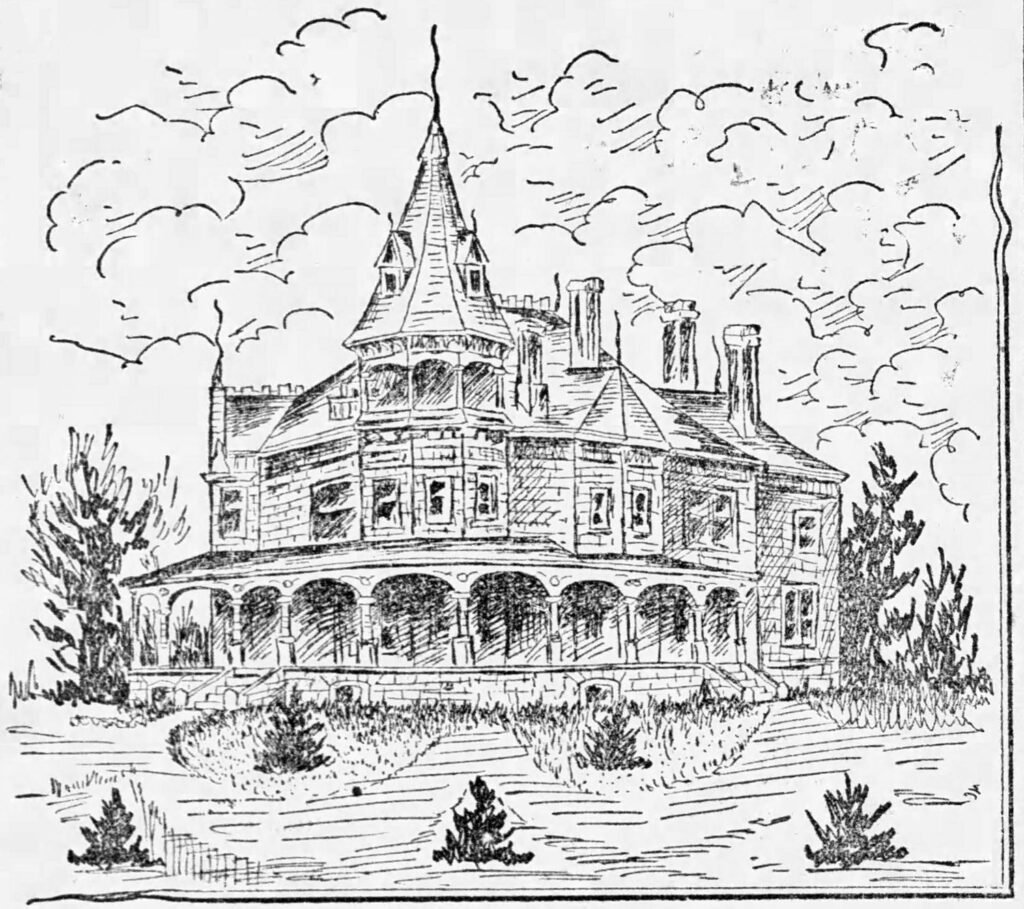

W.W. Goodrich. E.F. Gould Residence (1891, burned January 28, 1918). Inman Park, Atlanta.1 2 The Background

The following article was published in the Manufacturers’ Record in 1892 and written by W.W. Goodrich, an architect who practiced in Atlanta between 1889 and 1895.

Here, Goodrich engages in the sort of masturbatory civic boosting that Atlantans devour, describing the city in such gushing, over-the-top terms that the article could be easily mistaken for parody.

That Goodrich saw fit to write this embarrassing concoction of lies and fantasy for a nationally distributed publication underscores how deeply Atlantans swim in their own illusion, convinced that they are somehow exceptional and superior to other cities.

However, as any visitor in Goodrich’s time or now could attest, Atlanta is an aggressively mediocre city with scant culture and no distinguishable identity — the most defining feature is its population of conceited and ignorant inhabitants who loathe and despise each other while desperately seeking validation for their delusions of grandeur.

Indeed, few cities are so blithely arrogant as Atlanta, with so little of substance to show for it: Atlanta is the child who demands praise for using the toilet; the man with an average penis who is convinced he has a sizeable endowment; the insecure teenager desperate to be seen as popular, unaware that absolutely no one thinks about them.

Atlanta is a city built by frauds and liars, and Goodrich happened to be both. Before he arrived in Atlanta, he had a record of larceny and check fraud in Colorado, California, and Massachusetts,3 4 5 6 7 and many of the fantastical claims from his life story are easily disproven by the historical record.

Keep that in mind when Goodrich describes Atlantans as “moral heroes”, refers to the city in utopian terms as a place where “democrats and republicans work harmoniously for the public good”, and compares the city’s antebellum architecture (no, Sherman didn’t burn all of it) to that of ancient Greece.

Halfway through, the article turns into an advertisement for Georgia marble, a material so prohibitively expensive for use in construction that even the Georgia State Capitol was built with cheaper Indiana limestone.8

Shortly before writing this article, Goodrich toured the Georgia Marble Company’s quarry,9 and he may have been an investor in the business. Goodrich was also the designer for two of the marble buildings he lists here: the Herald Publishing Company building and the R.F. Gould house in Atlanta’s Inman Park.10

Goodrich concludes the article by praising the architecture of Atlanta, which then, as now, consisted almost entirely of artless, watered-down imitations of superior designs from better cities — often a decade or more out of fashion by the time Atlantans in their insecure posturing began demanding them.

“Atlanta has no style of architecture”, Goodrich exclaims. “This shows the wisdom of her architects.” Or as G.L. Norrman more accurately described Atlanta architecture: “The prevailing style is no style at all.”9

Atlanta’s Unique, Composite and Attractive Architecture.

By W.W. Goodrich

The hero rises above his environment, and ennobles mankind.

The people of Atlanta are moral heroes, who have put themselves in touch with each other and with their countrymen of our common land.

Here democrats and republicans work harmoniously for the public good, eschewing partisanship and striving in accord to upbuild a great city. Here is a charity between the vast political parties that commands admiration.

The blending of opposite political forces and opinions and the burial of dead issues have brought Atlanta to the front, and built her wonderfully up.

The architecture of Atlanta is progressive; from the simple taste of the artisan to the mansion of the rich is but a step, and the spirit of all, even the humblest, is to betterment. Under this universal inspiration Atlanta is surely marching to permanent superiority of architecture.

Before the war architecture was a blending of the Jacobian and the Colonial, of which excellent examples are still extant, the fluted columns of the simple orders, in bold effrontery, giving a classic invitation to come in and hear the oratory of the old masters of that art, now almost extinct. Looking on these facades I almost imagine I am in the classic land of Greece, in the temples of the gods, listening to a Socrates.

When Sherman destroyed Atlanta he little thought, probably, that a city would arise upon its ruins. Could he now look from the aspiring roof of the stately Equitable building he would see a grand metropolis on the wreck of old Atlanta, and on every hand majestic monuments of architects’ skill, and beautiful structural facades that fascinate the vision and compel the admiration of the most careless observer.

The principal building material for architectural effect and artistic embellishment is from the Georgia Marble Co.’s quarries at Tate, Pickens county, Ga. This marble leads the world. It is the granular marble, that resists all atmospheric action, stands all strains and finishes in a superb and harmonious whole. And this marble can be used at no greater expense than the finer grades of pressed brick.

Among the structures wholly or in part of Georgia marble are these:

- Herald building, daily newspaper, entire front.

- The R.F. Gould residence, wholly of marble, even the chimneys of this imperial stone, beautifully carved, and the heat and acids of the smoke do not tarnish the chimneys in the least.

- The Equitable building, in part.

- The Inman Building, in part.

- The High building, in part.

- The Aragon Hotel, in part.

And there are many others wholly or in part marble throughout Atlanta.

In all my experience with building stones Georgia marble gives me the greatest satisfaction for a perfect building material that will last and not be affected by heat or cold, nor the action of frost in freezing.

I have seen the cities of the growing West spring up in a day, figuratively speaking. They have their set back, but Atlanta grows on, and no matter what the financial state of the land at large, she climbs higher with her sky scrapers.

Her homes have more of architectural merit with each passing period or building construction. Each new house builder vies as never before to outdo his friend in home building and in home comforts. There is no accepted or popular pattern, no slavish imitation of any model, however liked, no wholesale adoption of architectural fashions, but a sturdy originality and independence of taste and idea that are always seeking and finding new effects and comforts.

Atlanta has no style of architecture. This shows the wisdom of her architects. We see a picturesque blending of all styles, the best of all styles grouped in a myriad of beautiful and harmonious, but differing and exquisitely unlike wholes. Such a composite and yet symmetrical and attractive architecture was never before seen, the outcome of a growing architectural taste, and presenting with absolute freedom from copied uniformity a rare and delightful variety and originality of gems of architectural beauty.

Every residence is different, and new combinations of grace and convenience constantly enrapture the eye.

The democracy in architecture relieves the sky line, and in a wholesale innovation, wherein monotony is destroyed, a scenic effect is given to the streets and lawns that could not be obtained any other way, and that makes Atlanta the very ideal of architectural taste and loveliness.11

References

- Illustration: “Pencil Sketch Of Marble Residence Of E.F. Gould”. The Atlanta Journal, April 21, 1891, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Edgewood Avenue House Is Destroyed By Fire”. The Atlanta Journal, January 28, 1918, p. 9. ↩︎

- “Held to Answer”. Rocky Mountain News (Denver), March 26, 1881, p. 2. ↩︎

- “Probably a Sharp Swindler”. Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), November 27, 1883, p. 3. ↩︎

- “An Old Fraud Heard From”. Los Angeles Herald, March 16, 1884, p. 4. ↩︎

- “A Worthless Check”. The Boston Herald, November 27, 1883, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Operation With Checks”. Boston Daily Advertiser, November 27, 1883, p. 8. ↩︎

- “The Capitol Contract”. The Atlanta Constitution, September 27, 1884, p. 7. ↩︎

- “A Delightful Excursion”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 20, 1892, p. 1. ↩︎

- “W.W. Goodrich & Co., Architects”. Norfolk Virginian (Norfolk, Virginia), August 17, 1892, p. 2. ↩︎

- Goodrich, W.W. “Atlanta’s Unique, Composite And Attractive Architecture.” Manufacturers’ Record, Vol. 22, no. 4 (August 26, 1892), p. 64. ↩︎