The Background

The following article was published in the Manufacturers’ Record in 1892 and written by W.W. Goodrich, an architect who practiced in Atlanta between 1889 and 1895.

Here, Goodrich engages in the sort of masturbatory civic boosting that Atlantans devour, describing the city in such gushing, over-the-top terms that the article could be easily mistaken for parody.

That Goodrich saw fit to write this embarrassing concoction of lies and fantasy for a nationally distributed publication underscores how deeply Atlantans swim in their own illusion, convinced that they are somehow exceptional and superior to other cities.

However, as any visitor in Goodrich’s time or now could attest, Atlanta is an aggressively mediocre city with scant culture and no distinguishable identity — the most defining feature is its population of conceited and ignorant inhabitants who loathe and despise each other while desperately seeking validation for their delusions of grandeur.

Indeed, few cities are so blithely arrogant as Atlanta, with so little of substance to show for it: Atlanta is the child who demands praise for using the toilet; the man with an average penis who is convinced he has a sizeable endowment; the insecure teenager desperate to be seen as popular, unaware that absolutely no one thinks about them.

Atlanta is a city built by frauds and liars, and Goodrich happened to be both. Before he arrived in Atlanta, he had a record of larceny and check fraud in Colorado, California, and Massachusetts,3 4 5 6 7 and many of the fantastical claims from his life story are easily disproven by the historical record.

Keep that in mind when Goodrich describes Atlantans as “moral heroes”, refers to the city in utopian terms as a place where “democrats and republicans work harmoniously for the public good”, and compares the city’s antebellum architecture (no, Sherman didn’t burn all of it) to that of ancient Greece.

Halfway through, the article turns into an advertisement for Georgia marble, a material so prohibitively expensive for use in construction that even the Georgia State Capitol was built with cheaper Indiana limestone.8

Shortly before writing this article, Goodrich toured the Georgia Marble Company’s quarry,9 and he may have been an investor in the business. Goodrich was also the designer for two of the marble buildings he lists here: the Herald Publishing Company building and the R.F. Gould house in Atlanta’s Inman Park.10

Goodrich concludes the article by praising the architecture of Atlanta, which then, as now, consisted almost entirely of artless, watered-down imitations of superior designs from better cities — often a decade or more out of fashion by the time Atlantans in their insecure posturing began demanding them.

“Atlanta has no style of architecture”, Goodrich exclaims. “This shows the wisdom of her architects.” Or as G.L. Norrman more accurately described Atlanta architecture: “The prevailing style is no style at all.”9

Atlanta’s Unique, Composite and Attractive Architecture.

By W.W. Goodrich

The hero rises above his environment, and ennobles mankind.

The people of Atlanta are moral heroes, who have put themselves in touch with each other and with their countrymen of our common land.

Here democrats and republicans work harmoniously for the public good, eschewing partisanship and striving in accord to upbuild a great city. Here is a charity between the vast political parties that commands admiration.

The blending of opposite political forces and opinions and the burial of dead issues have brought Atlanta to the front, and built her wonderfully up.

The architecture of Atlanta is progressive; from the simple taste of the artisan to the mansion of the rich is but a step, and the spirit of all, even the humblest, is to betterment. Under this universal inspiration Atlanta is surely marching to permanent superiority of architecture.

Before the war architecture was a blending of the Jacobian and the Colonial, of which excellent examples are still extant, the fluted columns of the simple orders, in bold effrontery, giving a classic invitation to come in and hear the oratory of the old masters of that art, now almost extinct. Looking on these facades I almost imagine I am in the classic land of Greece, in the temples of the gods, listening to a Socrates.

When Sherman destroyed Atlanta he little thought, probably, that a city would arise upon its ruins. Could he now look from the aspiring roof of the stately Equitable building he would see a grand metropolis on the wreck of old Atlanta, and on every hand majestic monuments of architects’ skill, and beautiful structural facades that fascinate the vision and compel the admiration of the most careless observer.

The principal building material for architectural effect and artistic embellishment is from the Georgia Marble Co.’s quarries at Tate, Pickens county, Ga. This marble leads the world. It is the granular marble, that resists all atmospheric action, stands all strains and finishes in a superb and harmonious whole. And this marble can be used at no greater expense than the finer grades of pressed brick.

Among the structures wholly or in part of Georgia marble are these:

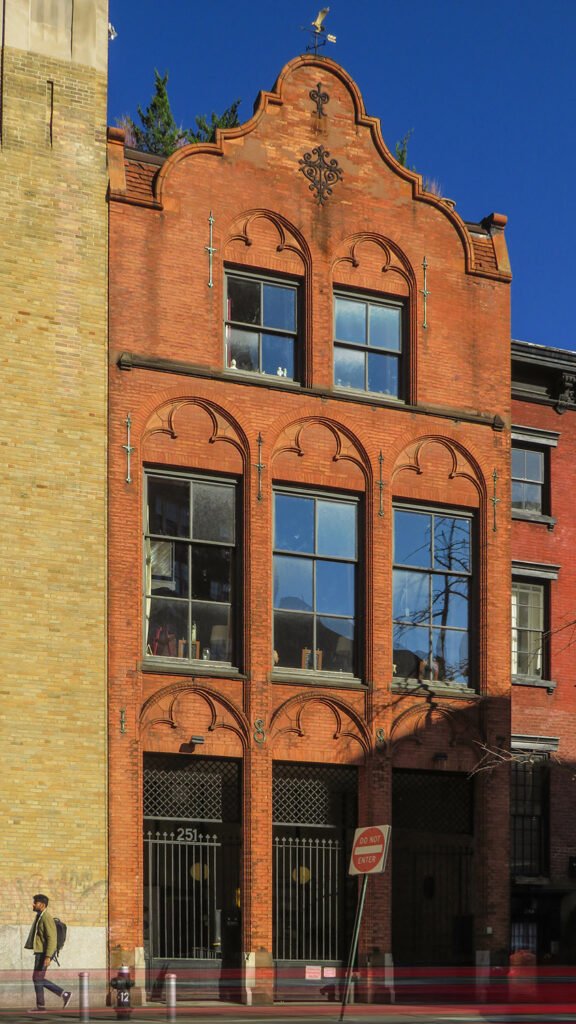

- Herald building, daily newspaper, entire front.

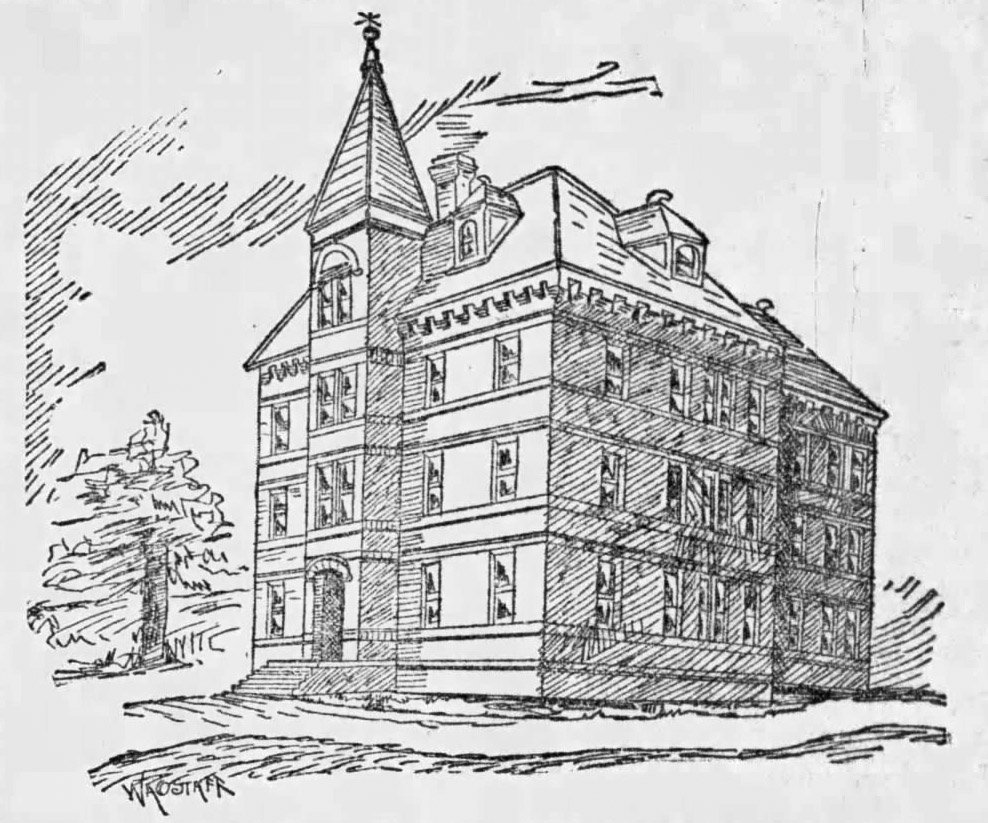

- The R.F. Gould residence, wholly of marble, even the chimneys of this imperial stone, beautifully carved, and the heat and acids of the smoke do not tarnish the chimneys in the least.

- The Equitable building, in part.

- The Inman Building, in part.

- The High building, in part.

- The Aragon Hotel, in part.

And there are many others wholly or in part marble throughout Atlanta.

In all my experience with building stones Georgia marble gives me the greatest satisfaction for a perfect building material that will last and not be affected by heat or cold, nor the action of frost in freezing.

I have seen the cities of the growing West spring up in a day, figuratively speaking. They have their set back, but Atlanta grows on, and no matter what the financial state of the land at large, she climbs higher with her sky scrapers.

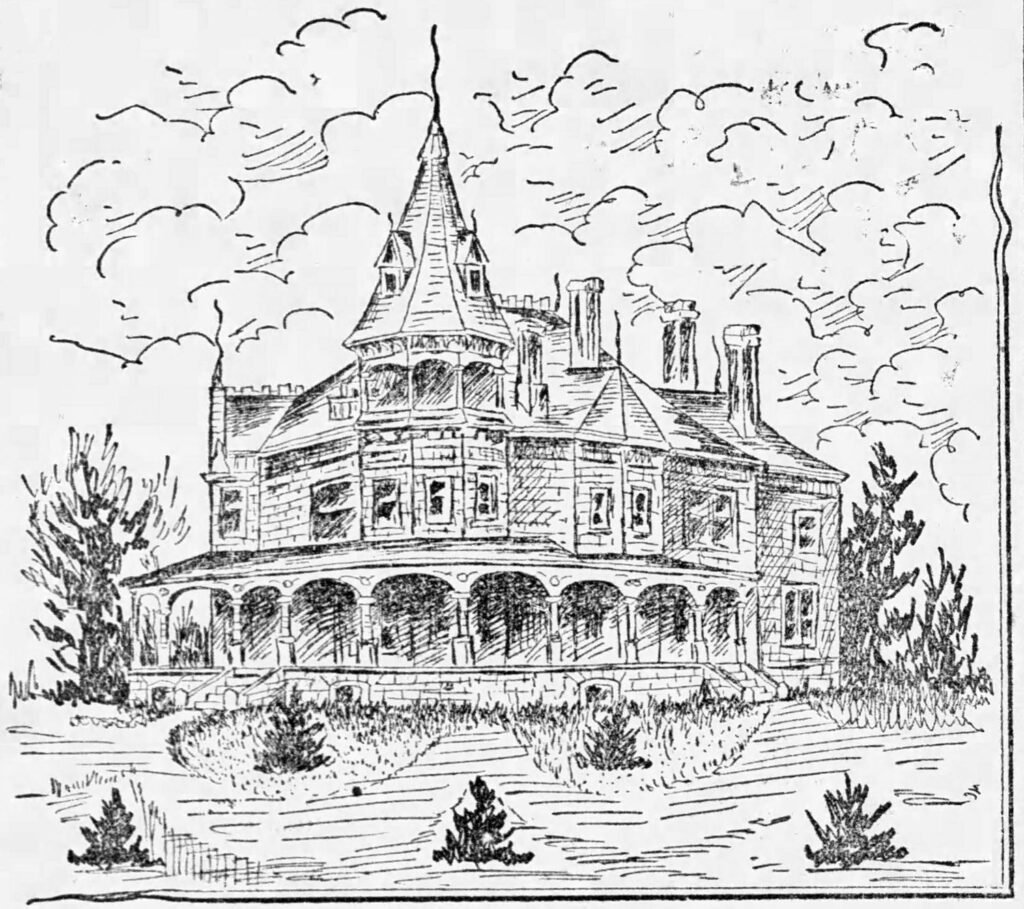

Her homes have more of architectural merit with each passing period or building construction. Each new house builder vies as never before to outdo his friend in home building and in home comforts. There is no accepted or popular pattern, no slavish imitation of any model, however liked, no wholesale adoption of architectural fashions, but a sturdy originality and independence of taste and idea that are always seeking and finding new effects and comforts.

Atlanta has no style of architecture. This shows the wisdom of her architects. We see a picturesque blending of all styles, the best of all styles grouped in a myriad of beautiful and harmonious, but differing and exquisitely unlike wholes. Such a composite and yet symmetrical and attractive architecture was never before seen, the outcome of a growing architectural taste, and presenting with absolute freedom from copied uniformity a rare and delightful variety and originality of gems of architectural beauty.

Every residence is different, and new combinations of grace and convenience constantly enrapture the eye.

The democracy in architecture relieves the sky line, and in a wholesale innovation, wherein monotony is destroyed, a scenic effect is given to the streets and lawns that could not be obtained any other way, and that makes Atlanta the very ideal of architectural taste and loveliness.11

References

- Illustration: “Pencil Sketch Of Marble Residence Of E.F. Gould”. The Atlanta Journal, April 21, 1891, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Edgewood Avenue House Is Destroyed By Fire”. The Atlanta Journal, January 28, 1918, p. 9. ↩︎

- “Held to Answer”. Rocky Mountain News (Denver), March 26, 1881, p. 2. ↩︎

- “Probably a Sharp Swindler”. Daily National Republican (Washington, D.C.), November 27, 1883, p. 3. ↩︎

- “An Old Fraud Heard From”. Los Angeles Herald, March 16, 1884, p. 4. ↩︎

- “A Worthless Check”. The Boston Herald, November 27, 1883, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Operation With Checks”. Boston Daily Advertiser, November 27, 1883, p. 8. ↩︎

- “The Capitol Contract”. The Atlanta Constitution, September 27, 1884, p. 7. ↩︎

- “A Delightful Excursion”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 20, 1892, p. 1. ↩︎

- “W.W. Goodrich & Co., Architects”. Norfolk Virginian (Norfolk, Virginia), August 17, 1892, p. 2. ↩︎

- Goodrich, W.W. “Atlanta’s Unique, Composite And Attractive Architecture.” Manufacturers’ Record, Vol. 22, no. 4 (August 26, 1892), p. 64. ↩︎