- Fox, Catherine. “New Emory student center like an amiable, multilevel Main Street”. The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, March 8, 1987, p. 4-J. ↩︎

- Photos: Goodbye to the DUC | Emory University | Atlanta GA ↩︎

This is the fourth in a series of articles written for The Atlanta Journal in 1890 and 1891 by W.W. Goodrich, an architect who practiced in Atlanta between 1889 and 1895.

Aimed squarely at the upper-class audience who could afford the services of an architect, here Goodrich provided an exacting and plodding description of a hall and reception room decorated in the Colonial Revival style that was then becoming fashionable in Atlanta’s wealthiest homes.

At the time, interior design as a dedicated profession was emerging in larger cities like New York and Chicago, but in Atlanta, it was still primarily the domain of architects — in particular, L.B. Wheeler and W.T. Downing were popular for their interior design skills.

Goodrich affected a lofty and condescending tone typical of the era, when designers — usually men — lectured their readers — primarily women — on how to decorate their homes in a manner that was considered cultured, refined, and in “good taste”.

A Chapter on Interior Decoration.

A Roomy Reception-Room and Hall.

An Article that Will Prove of Special Interest to the Ladies – Description of Beautiful Decorations for a Reception Room.

Written for the Journal.

Of the numerous styles of design applicable to the treatment of a reception room and hall the Colonial is one of the most pleasing, combining, as it does, the severe and studied simplicity of classic form with a delicate and distinctive grace and daintiness of detail. As one of the first principles of design is adaptability to requirements, the use to which the room is to be put should determine not only the practical essentials of convenience and utility, but also the impression which is to be made on the minds of its occupants by their surroundings, and this impression should coincide as nearly as possible with the thoughts and objects which will be uppermost in their minds. As such a room is devoted to the formalities of society, the treatment of its design should be formal and of studied simplicity. Any attempt at display or indulgence in eccentricities of design, either in wood finish, furniture, hangings or decorations, any violent or startling combinations of color, any pictures or bric-a-brac sufficiently conspicuous and out of keeping with their surroundings to attract immediate attention, would be evidences of bad taste and want of study in the effect of the whole.

Our reception room should consequently be, more than any other room, a harmonious whole, a dream of perfection, for it is here that we declare our taste and education to the world. If it is otherwise, the conception has been a failure, and the visitors will not find that appropriate ease in their surroundings which the occasion demands. It is infinitely better to make no attempt whatever at treatment than to give cause for the ignorant presumption of the would-be critic. A rich, pleasing, and above all, general effect should be the first impression conveyed to the mind on entering the successfully treated reception room, the whole scheme being so carefully studied that no one thing should be given undue prominence, but everything should participate in and be subservient to the effect of the whole, and then this effect will have the “refinement and charm of a fascinating and cultivated woman dressed in perfect taste.” Great care should be taken to produce the exact shades of colors desired, and it is important that those selected should be becoming to the “mistress of the house”, for if otherwise, she will appear at a disadvantage and out of place with her surroundings just when she should feel and appear at her best The most satisfactory results can be obtained by the general use of one or two color at most, but these can be produced in two or more shades which, however, should vary but slightly. Many so-called reception rooms are used for various other purposes which would involve the consideration of other impressions to be expressed in the treatment of design, together with other practical essentials.

Our room is about fifteen feet square, with the four corners rounded, and the wall coving into the ceiling with a curve of about nine inches radius, having no molding at either intersection with the flat surfaces. The inlaid floor is highly polished and has a border of prima vera and satin wood with the center in strips of the former wood two inches wide laid vertically in each wall, and mitering at angles.

Prima vera is a beautiful golden yellow species of mahogany which is used on the Pacific coast for fine interior finish. The wood finish of the room is made in cherry, which is enabled with seven coats of a rich cream color and polished to a dull egg-shell gloss. Cherry is greatly superior to pine or white wood for enameling purposes, the grain being so close and the wood so hard that all moldings and detail, no matter how fine, are sharply and clearly produced, and the chances of denting or disfiguring in any way by constant use are greatly lessened. As the drawings show clearly the treatment of the woodwork, only a few general remarks are necessary to make them understood. All moldings and details are of the utmost delicacy, the sinking being but one-quarter of an inch.

The carvings are mostly composed of acanthus leaf, rendered quite flat, with an extreme projection of but three-quarters of an inch, those of garlands only having conventionalized flowers and leaves, all executed with the utmost delicacy, edges being sharply and clearly defined, but in no case having a projection of more than one-sixteenth of an inch, the high light edges and surfaces being daintily touched with silver throughout. The portion of frieze over windows is a transom light of silver leaded pink and cream colored opalescent glass, on the same plane with walls of room; below this is a silvered rod, with rings for draperies. The walls are hung with a warm shade of rose pink silk, perfectly plain, in vertical pleats about four inches wide. This silk is secured in place by hooks and eyes, and can be taken down, cleaned and put back again with but very little trouble. Just below the wood cornice is a valance of the same silk, divided into sections by narrow pipes, placed at equal intervals, the head of each hanging down and being slightly crushed. The valance is cut to hang in slight creases, but its lower edge follows around the room in a perfectly straight line, and is bordered by a cream-colored silk fringe two and one-quarter inches wide, corresponding to the epistylium over doors and windows. Just back of this fringe is a silvered rod, supported by hooks screwed into the walls, its surface showing at intervals through the reticulations. The window draperies are heavy ones being of satin damask, in the same rose pink as the wall hangings, but a shade darker with cream colored silk fringes, tassels and linings. A pair of silk lace curtains and a sash lace on silver rods subdue the daylight to the desired tone. The ceiling cove and that portion of the walls above the cornice molding are treated in five coats of oil color on plaster, rendered in cloudy effect, commencing at the cornice, in rose pink, grading lighter toward the ceiling, and finally to a cream color beyond the ornament on ceiling, the clouding being in cream and pink, very light and filmy, and irregularly introduced. At the intersection of cove and ceiling are two strands of braid in carton pierre, forming a framework on which base the decoration. This braid comes down over the cove at intervals in two intertwining strands, and the intermediate spaces are filled by garlands of conventionally treated flowers and leaves, also produced in carton pierre, not over three-eights of inch in relief at great delicacy, both these and the braid being daintily silvered on high lights. Festoons of small discs hang above and below each garland, and acanthus buds and sprays spring from intermediate loops of the braid, flowing out onto ceiling and down into cove. The ornament is mostly cream in color, although where the clouding happens to be cream it has a very light pinkish tone, and in some places hardly distinguishable from the ground color; or, the whole treatment has a dreamy, atmosphere effect, impossible to describe, and must be seen to comprehend. All ornament is, of course, produced without any shadow or attempt at false relief, as under no circumstances whatever is such a treatment allowable. The furniture is like the finish, made in cherry and enameled in a rich cream color. It consists of the following pieces: A window seat about six feet long, having a cushion six inches thick and a large detached soft pillow, the edges of both being finished with a cord, which, on the cushion, is made into corner knots. A light divan five feet long, two arm chairs to match and two reception chairs complete the seating capacity of the room. The bottoms of all legs are shod with small silver boots, having casters on the front and rubber bearings on the back legs to prevent too free and easy a movement over the polished floor. All seats are upholstered plain, that is, not tufted, and the colorings are or figured silk tapestry, worked with bunches of flowers and leaves in delicate shades of dull blue, pink and green, on a light cream ground, the goods being mostly ground and showing very little of the other colors. There is a center table elliptical in shape, has silvered claw feet, and a Mexican onyx top of rich creamy tone. The cabinet has clear plate glass, with silvered leads in doors and sides, a French plate mirror back and three plate glass shelves, the piece being finished equally well both inside and out. All this furniture has the most delicate possible details of moldings and carvings, and is daintily lined and touched with silver throughout. Two large, white, bear skin rugs form the only floor covering.

W.W. Goodrich1

This is the third in a series of articles written for The Atlanta Journal in 1890 and 1891 by W.W. Goodrich, an architect who practiced in Atlanta between 1889 and 1895.

The title of the article is misleading, as Goodrich provided no advice for builders here — they wouldn’t take it anyway. Instead, this article delves into the design of doors, porticos, and other building entries, which allowed Goodrich to whip out such fancy architectural terms as “pronaos” and “antæ”. He obviously read Vitruvius at some point.

Goodrich’s writing style was overlong and overwrought, and you have to wonder how many people actually read this insufferably boring article when it was published — certainly not the newspaper’s editor or proofreader, as the article is chock full of typos and grammatical errors.

Given his grandiose ramblings on the subject, you’d think Goodrich was some genius of architecture, but if you look at the quality of his work, it’s clear he was nothing more than a run-of-the-mill designer with delusions of grandeur.

And that’s the nicest thing you’ll hear me say about him.

A Chapter On Beautiful Entrances.

Houses That Speak to Beholders.

Tame, Flat and Uninteresting Building — Hospitable and Polite House –An An [sic] Article that will Prove Interesting to Journal Readers.

Written for the Journal.

Has anyone ever felt or been impressed by the character of an ignoble or imposing entrance. The insignificance and meanness of a narrow, cramped doorway is as certainly experienced as a sense of nobility and grandeur is awakened by the sight of a great cathedral. Not only, however, in edifices of public character such as these do we feel the influence of the entrance; we find that it impresses an important character on buildings of an official and private class. A small and insignificant entrance stamps the character on the building; in effect it says to every passer-by, “I am only intended for private use.” On the contrary, the wide doorway invites entrance, it proclaims to every observer free and unrestricted ingress, and it stamps the building with an hospitable character. No other feature of a building addresses itself more directly to the eye than the entrance. Every good architecture has a language of expression of its own; the modes by which it gives expressions are few, and may in a word be said to symbolize or represent corresponding qualities or emotions of the mind. Thus we can make a building look vapid and tame by flat treatment and want of vigorous features, or we can make it frown and strike terror to the beholder by massive treatment, bold projections, and overhanging cornices; we can give it an air of amusement and gloom by windowless walls and by severe details; and we can make a building hospitable and polite by harmonious arrangements of the features, wide apertures and ornamental details.

This phonetic quality of architecture is as universal and as easily learned as the qualities of musical composition, or the varieties of rythm [sic] and harmony which expresses the grave and sprightly, the solemn and the frivolous. It has been said that an overture without words can express nothing; but all who can appreciate fine musical competitions know how eloquent and impressive certain passages are in appealing to the emotions and heart. In architecture likewise, though the differences of expression may be few, they are clearly pronounced, and the modes by which they are produced appeal with equal power to even the unlearned and artistic person. Thus we need not inform the least observant the effect that is produced of an excess of a paucity of openings in a building. A wide open fenestration expresses life and liveliness, large apertureless wall spaces gloominess and dullness. The most illiterate and least artistic can appreciate the difference between these conditions of building. The large paned windows of the modern villas as certainly express sprightliness and vivacity as the massive unpierced walls of a goal do gloom and austerity.

The entrance doorway has always appeared to us to be an equally powerful means of obtaining character of a facade, making it inviting or hospitable, sullen or selfish, and it is worth while to consider it as a very important feature in design.

There are several varieties of entrance; the most generally known may be broadly classed under the simple doorway, the projecting entrance and the recessed entrance. Of the second class, the porch or portico is a representation, and of the third, the open vestibule. Each of these kinds admits of many varieties, according to the style chosen and the purpose of the building. The style rather than the purpose of the building has been chiefly taken by architects as the only rule in the matter, and thus it happens that a few conventional modes of treating the entrance continue to be used, in total forgetfulness or in ignorance of what is demanded by purpose and expression. Of all forms of entrance perhaps no more noble or majestic can be found than the classic portico or pro-style arrangement in front of the cella; no meaner than the ordinary doorway in a flat wall. The classic and Italian architect never produced a more impressive entrance than the arrangement known as “in antis,” in which the temple of the building is entered through a pronaos or outer open covered space between two columns and the doorway. In the large and more important temples columns were placed in front of the antae, making a deeper covered space or portico. What is in classical nomenclature known as the “pronaos,” is, in Italial [sic] architecture, a kind of screened vestibule, recessed from the front wall. But as in other inventions of the ancients, modern architects frequently travesty this feature. They make it too shallow to be of value, or make it so small as to become ridiculous. The opening occupied by the columns between the antæ should bar some proportion to the facade, the larger the more dignified and impressive, it should form a convenient shelter from the weather, and should therefore be proportionately deep.

To lay down any rules of size would be superfluous and misleading, for it is a feature that should be planned in conjunction with the internal walls of the vestibule or hall. In a public edifice, as a hall, size is of importance, though it would appear the dimensions of the portico is accounted a small matter, the subject being left to the accidents of planning rather than to destination. We often find public edifices with meagre entrances, and private villas with spacious porticos. If we look at mediæval [sic] edifices, we shall find the noblest of our cathedrals have imposing entrances. The grand triple portals of Amiens and Rheims [sic] are majestic works of sculptural architecture, depth being obtained partly be [sic] external projection, which is gabled, and partly by recess in the wall. The splay of the jambs and seried arch members filled with sculpture play a great part in giving apparent depth to the portal, a principle followed also by the mediæval architects, in diminishing the members, shafts and statues as they approached the plane of doorway. Height, too, was not sacrificed, the tympana are richly sculptured, and the apices of the outer arch mouldings reach to a full third of the height of facade. The entrances to our own cathedrals are less important features, but are largely obtained by recess in the thickness of the wall.

Projecting porticos and porches form a notable kind of entrance, and their chief use is in obtaining external shelter and protection from the weather. Projecting arrangements forcibly express entrance, and are probably of all forms the least tractable in the hands of the architect. In towns they require the setting back of the building, and are, therefore, rather wasteful of area. The chief failure in this mode of expressing the entrance is the want of connection with the building. Unless the porch is designed with special reference to the elevation, it has the appearance of a clapped on adjunct, and this is the common weakness of the porch. From all we have said there a few rules to be observed which may be enumerated. First, the entrance should accord with the purpose of the building in size; second, in its architectural treatment and decoration it should express its function of access and shelter clearly, and its lines should be made to unite with those of the facade; third, a half projecting and half recessed entrance is more pleasing and desirable than a flat doorway. To these, a fourth principle should be added–that the external entrance should correspond with the internal arrangement. A wide entrance or portico should always have an inner vestibule or hall of similar width and importance; and sense of disappointment is otherwise at once felt on passing the external entrance and find a narrow hall within. Yet this is a very common fault in entrance designing which has been studied in elevation and not in plan. We often see porticos and porches stuck on, having no reference whatever to the internal walls. The walls of entrance internally are suddenly reduced to the width of a corridor, and the visitor at once realizes the deception practiced upon him of a counterfeit portico–having no connection whatever with the hall inside. In short, the vestibule and hall should be a continuance of the entrance, and it is better, to enlarge than diminish its width and to increase rather than lessen its architectural embellishment. The object for any entrance hall should be to invite the visitor, not to repel him, as he passes the threshold. It is a feature upon which the ablest architects of all ages have exercised their highest skill, and its treatment, both architecturally and decoratively, ought to be to conduct the visitor to the apartments, instead of by meanness or ostentation to arrest his footsteps, or to disappoint his expectations of the interior.

W.W. Goodrich.1

This is the second in a series of articles written for The Atlanta Journal in 1890 and 1891 by W.W. Goodrich, an architect who practiced in Atlanta between 1889 and 1895.

In this article, Goodrich informed readers on the attributes of a qualified architect, at a time when the building industry was almost entirely unregulated — particularly in the Southeast — and anyone could market themselves as an architect regardless of training or experience.

One of several Atlanta architects who publicly advocated for increased oversight of the profession, here he called for an examining body to register architects, which was not established in the state of Georgia until 1919.1 2 3 4

And Its Scientific Requirements.

What Steps Are to Be Applied.

An Able and Comprehensive Paper on the Qualifications of an Architect–Buildings Without Claim to Architectural Merit.

Written for the Journal.

It would not be very easy to draw the line between a qualified and unqualified architect, because it is hard to say what the conditions of successful architecture are. There are many who have achieved a professional reputation by name, but whose buildings are not remarkable for any high quality, either as works of art or as successfully planned structures. There are others who are not known to fame whose works, though small, bear the impress of artistic ability. But the question still remains, what are the tests of good architecture, where should the scientific requirements end and the artistic begin? And until these points are decided it will be hard to apply a rule. The practice of architecture cannot be gauged like that of law or medicine by the number of briefs or patients, which are more or less accurately the measures of successful practice, as the fact that one man designs and carries out more buildings than another becomes no test of the artistic qualification. The oftener a physician prescribes or a surgeon operates, the more skillful he becomes–so in the practice of law; but it cannot be said of the architect’s work. There are hundreds of buildings eminently successful as works of skillful arrangement and construction, but which have little claim to architectural merit. Works of this class imply the profession of faculties of a high order and technical skill, all of which may be acquired without any art function. We have abundant examples of cleverly-arranged offices, schools and hospitals, which are without any of the qualities which render them artistic or even agreeable. Other buildings can be named that exhibit every attribute of artistic beauty, wholly wanting in the utilitarian requirements. Which of these two classes belongs to the architect? Those who make good building essential will answer that the first of these descriptions fulfill the object of architecture, and they will be found to include the largest number of people. Usefulness and sound construction are the tests. Publican criticism of architects’ work has generally proceeded on these grounds. Like the reputation of a great man, the merits of a building are of slow discovery. It is the public test of fitness which approves or otherwise. Not one in a thousand can see anything in a handsome, elegant, or picturesque building to put it in the balance against fitness and convenience. Those qualities on paper may gain it for the premium; but the public are the first to find fault with insufficient or awkward arrangements, bad lighting, ventilation, and so on. They may admire a handsome elevation, but they estimate its value at an exceedingly low price. Like good poetry, architecture is understood only by the very few–those, we mean, who take a real pleasure in ordered arrangements, in picturesque handling of masses, in light and shadow. The popular admiration is not worth much when it comes to payment or a question of rates; fine architecture, like high class music or entertainments, sinks rapidly, and the real measure of appreciation or discernment is found to be very small. Fine art, then, being an intangible quality, is undervalued, and those who have to live by it are very few compared with those who deal with the more practical requirements of building. It follows that the architect’s qualifications will be estimated accordingly, and that they must be governed by the public demand. Hence the only successful condition of the architect is that he can accommodate himself to the times, not be too sensitive an artist, nor exacting in his tastes, but be a compliant man of business, a scientific builder.

Our experience of the profession points to the necessity of making the architect primarily a skilled arranger and constructor. Skill in arrangement and construction, however, applies to a variety of buildings intended for a multiplicity of purposes, and one man can never have more than once or twice in his life the opportunity of designing any one special building. In short, the qualifications vary for almost every description of building, and an architect who has acquired skill as a house designer may have no aptitude for designing a school or church. We can only say that there is a certain knowledge and procedure necessarily common to both. How to set about a plan is the first step; for if a man knows how to proceed he can soon solve the problem of any new building that may be presented to him. The experienced architect of one class of work goes to work unconsciously upon a truly logical basis. He knows by heart the requirements, say of a school room–a large array of types or precedents are ready in his mind. His mind agrees on a few principles, as, for instance, the light must enter on the left, desks must be placed along this side, the proportion of the room is regulated by the desks, and he sketches out a plan jointly by the aid of these principles and the types he has stored in his memory. The inexperienced does not proceed in this manner. He seeks precedents, and sets to work copying or arranging something by their aid, but without reference to data. The work fails because it has not taken account of facts; precedents are useful, as they show deductions from facts, but useless unless the latter are known. From which considerations we gather that in planning we have first to discover all the requirements, about lighting and intercommunication, and then by a synthetic process from particulars to generals, to arrange a general form that shall satisfy those data. As the naturalist and scientific observer from observing particulars and their relations can deduce a law, so the architect, who has a new problem of arrangement to solve, formulates a plan. So the function of every room may be met and expressed.

How to design a plan is one of the things the architect has learned. It is included in the course of his training. The statistics of plans are considered one of the primary attainments of the architect. We mean, by “statistics”, all those particulars derived from experience bearing upon dimensions, cubic space, light, positions of doors and fireplaces, seating accommodations, etc. Thus, in the design of a church, the statistics would include the proper distance between the backs of seats, space to each person. In the construction of a theater or concert hall the ascertained distance in front of, and laterally from, the stage or platform at which the human voice can be heard, the proportion of stage to auditorium, the “setting-up” of sections or “sighting” of the various parts of the house, the raking or stepping of the seats and fronts of the “circle” to the inacoustic curve, are among the facts which experience has established, and which cannot be departed from to any extent. The qualities upon which successful hearing depends, the requirements for fire construction, heating, and good ventilation, are among the main essentials of truthful architecture, and these are the points which the public considers they have a right to look for in the building designed by an architect. Many subtle and conflicting questions of construction arise out of the theory of acoustics–for instance, there are proper “lines” and setting-out of the seating and ceiling, the influence of ventilation, or the movement and direction of currents of air upon sound, the proper materials for the reinforcement of sound. When the day comes for registering the architect, one of the main purposes of the examining body will be to secure to each member a modicum of such applied science, to guarantee to the employer qualification in his architect shall put him far above the builder, who has learned construction empirically.

In short, it is the scientifically-trained builder that the public expects. We hear a few say that the architectural tests will be of no avail, for the public will still employ the practical builder. Yes, very true. They will employ him if they cannot get one any better; but the object of future legislation will be to create an improved class of builders–men trained in science, and who are experts in its application to the practical wants of the day. It is for the coming architect to make himself one of these, first of all, so that he may hold his own against the untaught builder, who has only learned one way of doing his work–not always the best or the most economical in its results. Building, like all other trades, has fallen into a groove, out of which mere workshop influence will never raise it.

W.W. Goodrich5

This is the 1st in a series of articles written for The Atlanta Journal in 1890 and 1891 by William Wordsworth Goodrich (1841-1907), professionally known as W.W. Goodrich, an architect who practiced in Atlanta between 1889 and 1895.

Here, Goodrich argued for the employment of a competent architect when building a home, at a time when the building industry was almost entirely unregulated — particularly in the Southeast — and anyone could market themselves as an architect regardless of training or experience.

Goodrich particularly emphasized the need for good quality plumbing — indoor plumbing was still an emerging technology available primarily to the wealthy, and dangerous and catastrophic plumbing failures caused by substandard materials and improper installation were common.

Some Valuable Hints By An Architect.

Points About How to Build a House

Give Your Suggestions to an Architect and Trust Him With the Work–A Professional Man Knows More Than a Non-Professional.

Written for the Journal.

To the prospective home-builder, I would address this warning: You are about to build or add to your present domestic or business accommodations. Possibly you have had some experience in planning and construction. Remember a good architect will save far more than his commission, and there is no economy in dispensing with his services.

The reason why houses are so ill-constructed, is not far to seek. The blame rests partly upon the builder, but a large share belongs to the owner’s ignorance of what is essential to a perfect house, or to his unwillingness to pay for it when pointed out by the architect.

While the architect has a recognized superiority in matters of taste and design, he is also better fitted to direct the great variety of artisans employed about a house. It is common but mistaken custom to give this direction to a contractor or builder, who is usually a mason or carpenter, and who is not thorough in his own trade, while lamentably ignorant of the details of other men’s work, which he has to superintend. The solo interest of such a man is to get through each job as soon as possible and with the least trouble and outlay. He is the plumber’s worst friend, when he winks at the latter’s failure to do justice to the owner’s interest, while, as he has no comprehension of the importance of good plumbing, he takes no pains to secure it. The practice of sub-letting plumbing to such men or any lump contractor is very objectionable and all sanitary details should have the personal supervision of the architect. The same reasoning will apply in the case of other departments of house construction and proves the necessity of competent mechanics.

Before undertaking any building or other like work it is always best to draw up a detailed specification, with plans, to ensure against errors or misunderstandings, which create disputes in settling accounts and to thus make it clear just what it is proposed to do, and what are the duties and obligations of all parties concerned. Detailed sketches and working plans will also be found useful, especially for explaining designs to persons not familiar with building operations. A building specification should be brief, concise, yet clear; but the terms should be specific, and particularly those relating to plumbing and drainage; the kind and character of each article or material named should be defined so as to prevent the substitution of an inferior article; and weight of pipes should be stated. And here it should be said that it is always safest and cheapest in the end to specify the best materials. The difference in first cost, for example, between (medium and heavy water supply or waste pipe or between) light and heavy lining for tanks or baths, is slight compared to the durability and safety of the better material. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link and the quality of material has a far more important bearing in plumbing than in other work. This is a matter of great importance and one in which owners are liable to be deceived. It is a common thing for unscrupulous plumbers to substitute light weight pipe, full of sand holes, where sound material is specified and there are no official tests for such material, only great watchfulness will guard against frauds of this kind. The rules of the New York board of health regarding the weight and quality of plumbing materials to be used in new houses may be consulted to advantage. In making contracts for plumbing it should be remembered that the lowest bidder may be the most expensive man in the end. No bid should be accepted at so low a rate that the mechanics who take the contract must either suffer loss or “scamp” the job and therefore be attempted to cheat at every step. Let the owner inquire about cost of materials and labor and make sure of his own protection that there is a living profit for the contractor, for he may be sure that the latter will “get even with him” in some way, and it is better that the owner should agree to pay a suitable price at the outset, than that his house should be ruined and the lives of its future occupants endangered by this common “penny wise” practice.

Two facts should be especially borne in mind by property owners. First, that a great saving can be made by having their sanitary arrangements made right in advance, instead of correcting them afterwards; and secondly, that a house in first-class sanitary condition will bring a much higher price than another which has only ordinary drainage arrangements.

When the house is building it is easy to run pipes in any direction, but when plastering has to be torn down and replaced, double expense is incurred. It is estimated that the difference between good plumbing and the average work of this kind does not exceed twenty-five percent of the original outlay.

If a compromise must be made because the owner’s purse cannot afford the best plumbing, then let the amount of the work be reduced, not the quality. It is far wiser to be satisfied with one really good plumbing appliance than with two inferior articles. Get the best under any circumstances. Let all the materials be sound and durable, and do not get anything merely because it is cheap; above all, remember that the cost of replacing a worn out or flimsy fixture with a good one, is usually almost equal to the cost of putting in a first-class article in the beginning.

The very first requisite before beginning to build a house, is to get good mechanics in every line of work.

If it asked “how am I to know a good plumber from another”, I answer how are you to know a good doctor or lawyer or architect – simply by taking pains to inquire and by avoiding the too common delusion that the cheapest man is the best. The only safeguard, is to employ a mechanic of known good character who has a reputation to lose, and who will be guided by his interest and his probity to do only first class jobs. If the public will insist on having good plumbing they will get it. If a man persists in buying sour bread or diseased meat no one pities him. Why then should we condole with one who engages the first plumber who comes along, without asking the least pains to learn his capacity or honesty, and who in consequence gets cheated? It would be amusing, if it were not so tragic in its consequences, to hear the common complaints of the duplicity of plumbers. The burthen of the story is always the same: “He was a stranger, I trusted him implicitly, and he deceived me.” We answer, why then did you trust a stranger? Next time take warning and find out something about those whom you employ and you will obtain men as worthy of your confidence in this calling as in any other.

Householders who are given to cursing the plumber will very often find, on examination, that their execrations would be more judiciously bestowed on themselves.

Having selected a competent architect, let the owner make up his mind not to hamper him by needless interference. He should take every precaution to secure a trustworthy man, and after giving him general instructions, let him carry them out in his own way. If the architect knows his business he can teach his client more than the latter can teach him. Nothing is more absurd than for people to presume to tell specialists how to carry on their specialty. This is especially the case with sanitary matters, in which amateur opinions are almost certain to be wrong, and wherein a little knowledge is most dangerous. Mr. Eidlitz takes the true professional ground when he says that “an architect, who permits a layman to decide upon the merit of his work, to gauge it, correct it, accept or refuse it – has already given up his position as a professional man.

W.W. Goodrich1

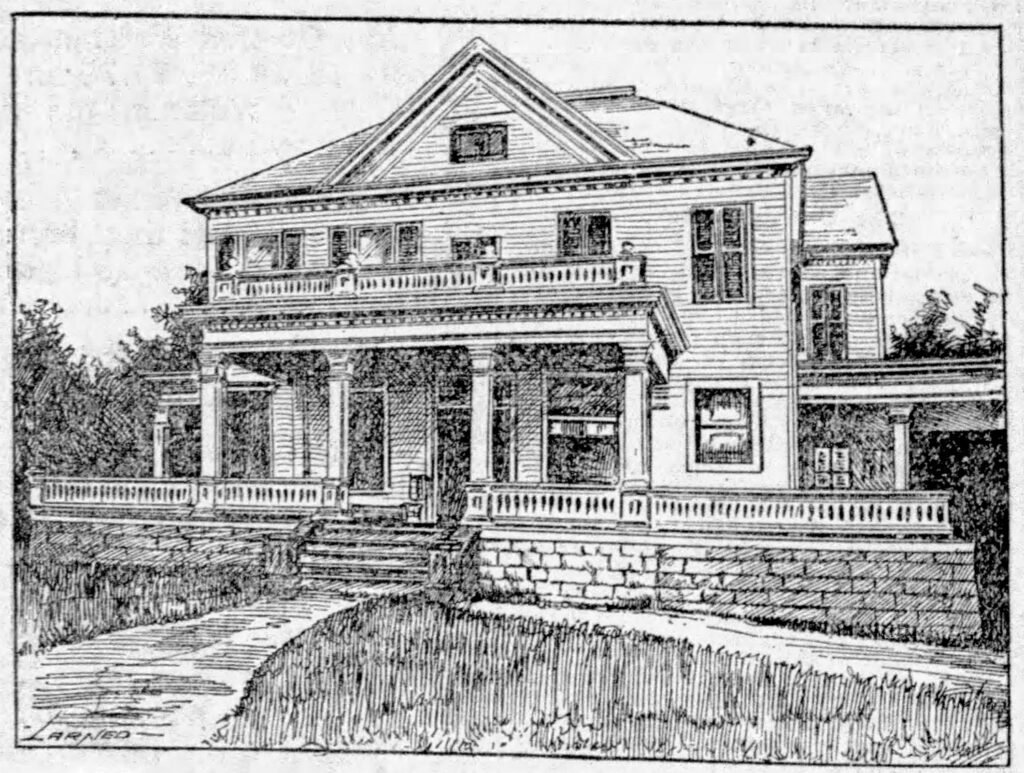

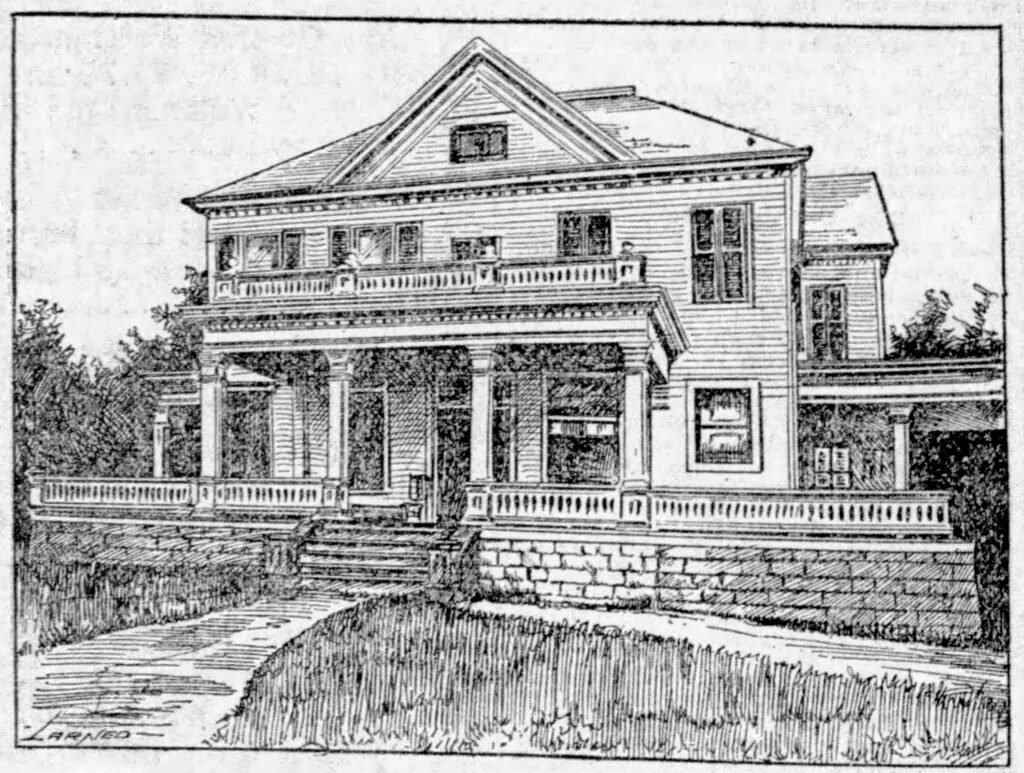

The following article was published in The Atlanta Journal in 1898, highlighting the “summer residence” of J.C.A. Branan in Kirkwood, then a suburban development located southeast of Atlanta.

Despite the Journal’s claim that the architecture was “unique”, it was anything but: while attractively designed in the Colonial Revival style, the 2-story home’s appearance was very similar to numerous residences around Atlanta at the time.

No information is provided about the home’s designer, and it may very well have been built by a contractor using plans from a pattern book.

The article was notable for than just showing off a house, however, as Branan’s residency in Kirkwood was controversial, and appears to have been a strategic political move.

When Branan built the home outside the city limits, his opponents questioned whether he should resign from Atlanta’s board of police commissioners1, although nothing seems to have transpired from the debate.

Branan must have had good political connections, because in late 1899, the Georgia governor signed a bill incorporating Kirkwood as a city and installing Branan as its mayor — without an election, mind you.

The move to incorporate Kirkwood was fiercely opposed by many of its residents, who filed a lawsuit against the state2 3and then held their own mayoral election in February 1900, with the “anti-incorporation” candidate winning over Branan.4 5

The following month, the Georgia supreme court repealed the law making Kirkwood a city, determining it to be unconstitutional.6 7 So much for that attempted power grab.

Branan made the “summer home” his permanent residence and died there in April 1927,8 9 10 five years after Kirkwood became part of Atlanta in 1922.11 12 Obituaries mentioned his status as Kirkwood’s former mayor, without noting that his tenure was both illegal and lasted less than 2 months.

The Branan home was located at 34 Boulevard Dekalb (later 1895 Boulevard Drive SE),13 and appears to have been demolished for the construction of Kirkwood Presbyterian Church’s educational building, which was built at the address in 1954.14 15

The church building was converted into a human services center in 1975,16 and still exists at the southeast corner of Hosea L. Williams Drive and Warren Street in the Kirkwood neighborhood.

It Is Located At South Kirkwood, Three and One Half Miles From the City–Is a Model Country House.

One of the prettiest suburban homes built about Atlanta in some time is that of Mr. J.C.A. Branan, member of the board of police commissioners. The house is now about completed, and Mr. Branan is receiving many congratulations on the beauty of the lot and house and surroundings. A few more details remain to be finished before the place will show up to its best advantage.

Mr. Branan’s home is located at the corner of Boulevard DeKalb and Warren street, near Kirkwood, and is situated on a beautiful three-acre lot, one of the best in the county. It is a high rolling piece of land, and the drainage is perfect. The lot fronts 328 feet on Boulevard DeKalb, and runs back 525 feet.

The house is a two-story frame structure, slate roof, and it is built in the best workmanlike manner. The architecture is unique and the house presents a fine appearance from every point of view. The lower story contains five rooms, all large and commodious, and a reception hall. Besides these rooms there are the store rooms, butler’s pantry and other small apartments. This floor contains the parlor, dining room, reception hall, and a large family room, and the rooms are so arranged that four of them and the reception room can be thrown into one large hall or connecting rooms.

Up stairs there are six large rooms, besides bath rooms and closets. The house is fitted with hot and cold water apparatus throughout, and it is a delightful place in every respect. The entire house is finished in yellow pine with a hard oil finish from top to bottom. There is a barn and servant’s house on the lot, and Mr. Branan is now having a fine windmill put up to furnish water for the place. He says the wind-mill will practically turn Chattahoochee river in that direction when the fine breezes of DeKalb county start the wheel.

The house is about three and one-half miles from the union depot in Atlanta and is directly on the Decatur line of the Consolidated street railway company. There is a fine road in front of the house, and Mr. Branan’s new home is delightfully situated in every respect.

The place is a costly one and makes a fine summer home for the popular police commissioner.17