From the Notebook

-

“St. Philip’s New Deanery In Course of Construction” (1898)

The Background

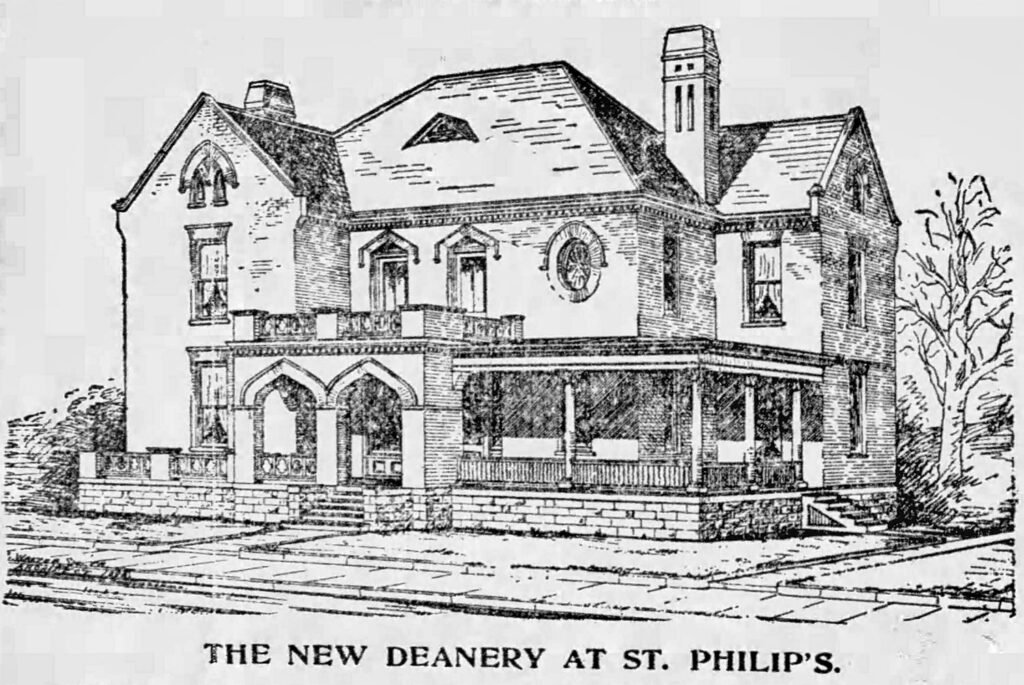

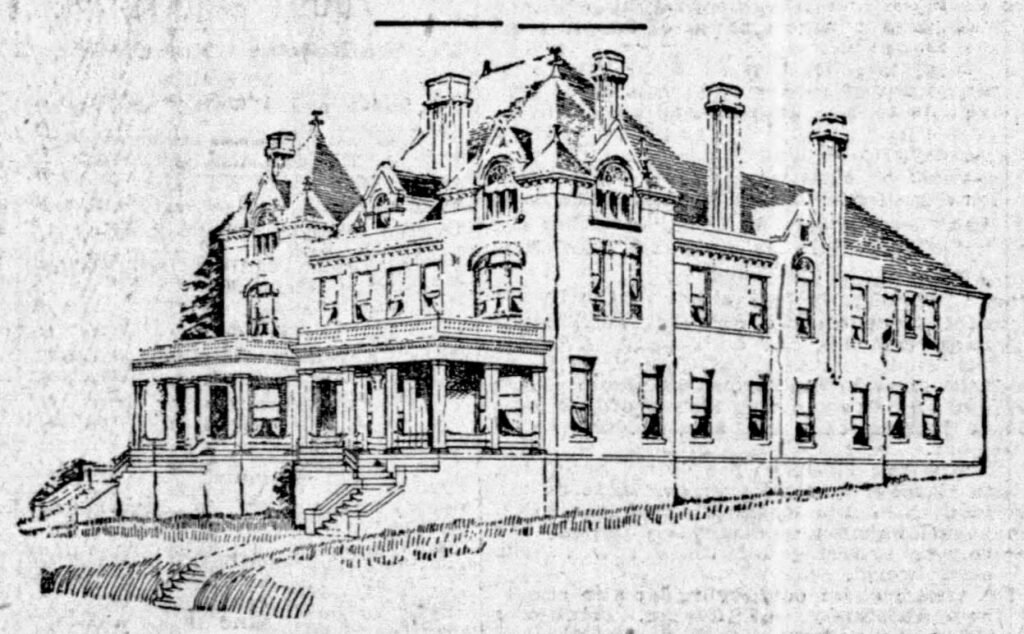

Separate from its series on model houses — but not dissimilar — The Atlanta Journal published the following article in September 1898, featuring an illustration of the “deanery” (pictured above) then being built for St. Philip’s Cathedral and designed by C. Walter Smith.

The Episcopal Cathedral of St. Philip is as old as Atlanta, established in 1847. Its original sanctuary served as a hospital for Confederate soldiers during the Civil War and was later occupied by Federal troops, who reportedly used it as a stable and bowling alley.1 2

The building was saved from Sherman‘s burning of Atlanta, allegedly after a priest from the nearby Church of the Immaculate Conception threatened to order all Catholic troops to leave the army if they torched his sanctuary. Because of St. Philip’s proximity to the Catholic church, both structures were said to be spared.3 4

Cute story, but like most things associated with Atlanta, it’s probably bullshit. In reality, Sherman’s forces primarily targeted military assets and burned less than half of the city,5 which at the time was a town of 22,000 people occupying an area significantly smaller than the current Downtown district.6 You’d never know it from the way Atlantans still drone on about it, though.

The antebellum St. Philip’s was instead destroyed by a tornado in 1878,7 8 replaced in 1882 with a Gothic-style sanctuary designed by John Moser,9 10 an Atlanta architect whose work in the city has been entirely lost to demolition.

For more than 85 years, the church occupied a large lot in the heart of the city at the northeast corner of Washington Street and Hunter Street (later Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive SE), directly across from the state capitol.

Mammon and racism beckoned, however, and in 1933, St. Philip’s moved 7 miles north to Buckhead,11 12 building a sprawling fortress at the intersection of Peachtree Road and Andrews Drive (a.k.a. “Jesus Junction”), where it remains cloistered today.

Located at 16 Washington Street, the deanery designed by Smith was built next to the 1882 sanctuary,13 and by 1899 was occupied by the church’s dean, Albion W. Knight.14 No floor plan was included with the Journal‘s article, but there were still several interesting aspects about the project that can be gleaned from the illustration and description.

- The building was ostensibly designed in the Gothic style, with drop arches and kneelered gables. However, the oval window and dentilled cornice were borrowed from the prevailing “colonial” style of the period. Smith’s eclectic composition clearly followed the lead of his former employer, G.L. Norrman, but unlike Norrman, Smith lacked the skill to blend incongruent elements into a cohesive composition.

- Smith’s design for the deanery also broke from his predecessor in two significant ways:

- G.L. Norrman rarely used the Gothic style and preferred the Romanesque for church projects.

- Smith’s design for the deanery included the use of “galvanized iron ornaments”, of which Norrman was a vocal opponent. “How can you expect your child to tell the truth when you have galvanized iron columns painted in imitation of stone on your front porch?”, he wrote in 1898.15

- The deanery was planned in a roughly “T” shape with protruding front and rear wings, which Smith used frequently in his residential works. The C.D. Hurt House, built in 1893 in nearby Inman Park, employed a similar design. G.L. Norrman was undoubtedly the architect for that project, and I suspect Smith was also heavily involved in its creation.

Former St. Philip’s deanery, circa 1910.16 The St. Philip’s deanery only housed the dean for 11 years. In 1909, construction on the first Washington Street viaduct blocked the home’s entrance, rendering it effectively unusable and leading the church to sue the city of Atlanta for damages.17

The city government then rented the structure in 1910, converting it into a school building to accommodate overcrowding at nearby Girls’ High School.18 19

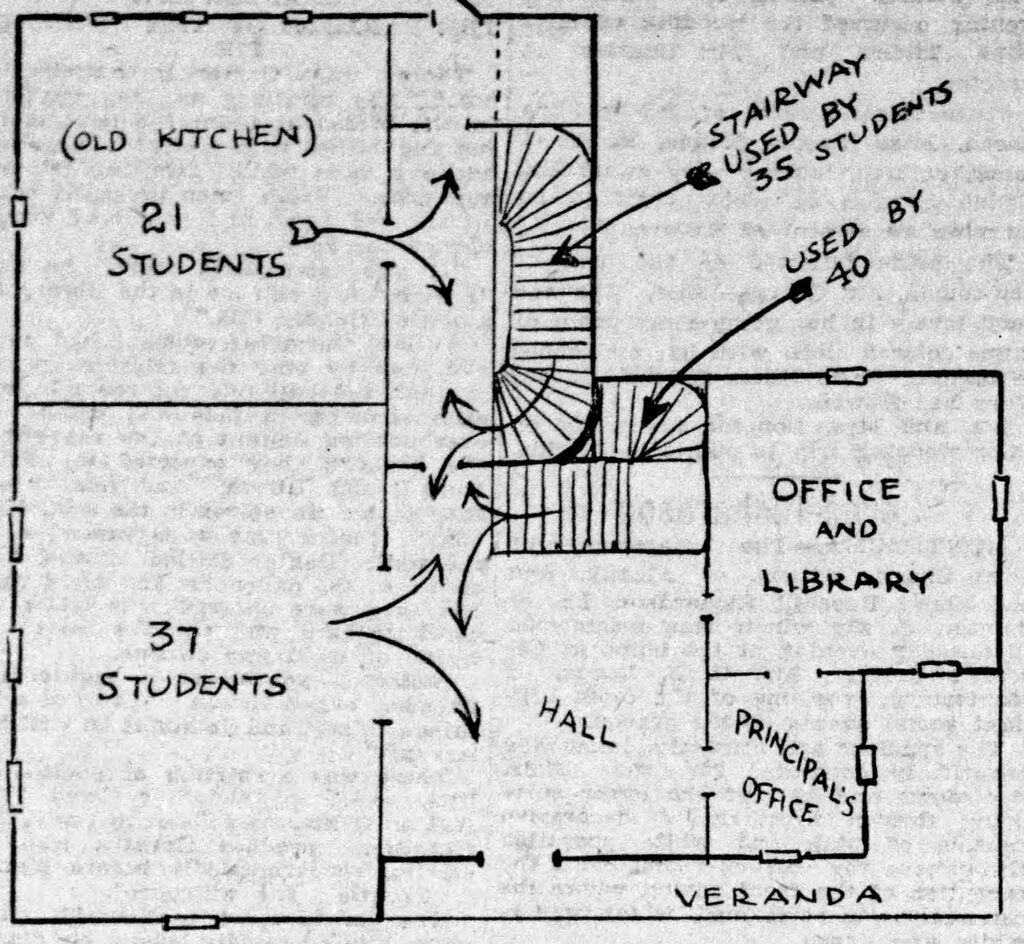

The condition of Atlanta’s schools at the time was abysmal, and the old deanery didn’t provide much relief. In January 1913, the Journal reported that 133 students were packed into the building, noting ominously: “If there were a fire…there would be many funerals in Atlanta homes.”20

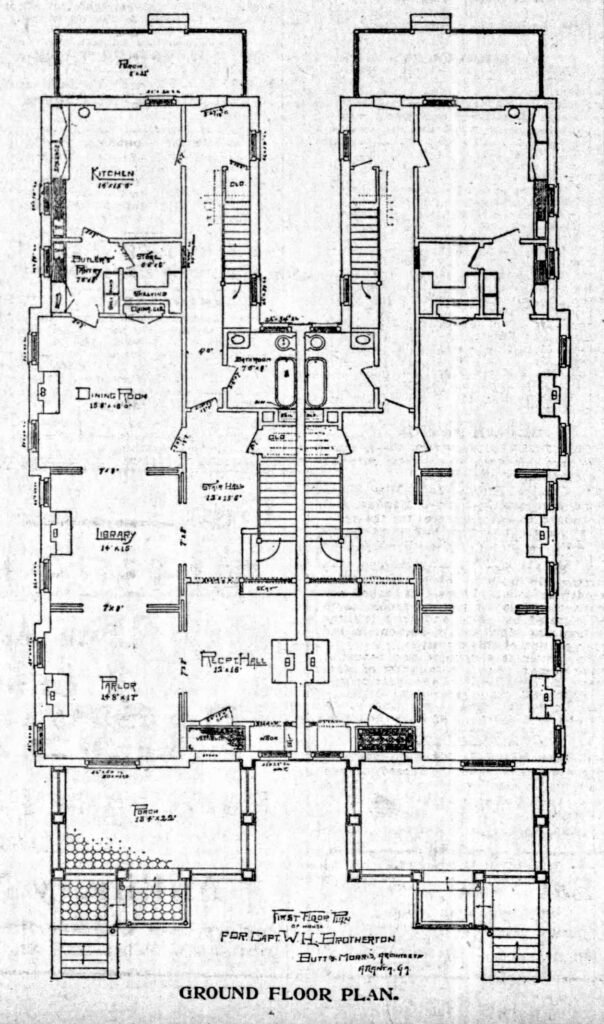

The same article included a rough sketch of the building’s floor plan (pictured below), which had been altered for school use but still hinted at Smith’s original design.

Sketch of floor plan for former St. Philip’s Deanery, circa 1913.21 The school vacated the building in August 1913,22 and it returned to use as the “church house”, used for meetings and community events. In 1916, the church’s new dean repurposed the structure to house “club rooms for working men and a school for needy boys and girls.”23 By 1917, the space was also being used as a public lunchroom by the Ladies’ Aid Society.24

The building was apparently still intact when St. Philip’s moved to Buckhead, and was presumably demolished along with the sanctuary in 1935.25 26

The property is now occupied by the State of Georgia’s Department of Agriculture building, completed in 1955.27

St. Philip’s New Deanery In Course of Construction

The above cut represents the deanery of St. Philips’ cathedral, which is in process of erection on Washington street. The plans are by C. Walter Smith and the motif is gothic in design and detail.

The building has brick walls and a granite foundation, with stone and galvanized iron ornaments.

The interior finish is worked out in plain, rich gothic, and the woodwork is of Georgia pine, highly polished.

The cost of the building will be about $4,000, and it will be pushed to early completion.

The design is an attractive one and reflects credit on both the architect and the authorities who adopted it.

The cathedral building is at the same time undergoing repairs and the appearance of the exterior of the wall will be entirely changed.28

References

- “First Episcopal Church in Atlanta”. The Atlanta Journal, July 29, 1923, p. 9. ↩︎

- Perkerson, Medora Field. “St. Philip’s Is 85 Years Old.” The Atlanta Journal Magazine, October 30, 1932, p. 3. ↩︎

- “First Episcopal Church in Atlanta”. The Atlanta Journal, July 29, 1923, p. 9. ↩︎

- Perkerson, Medora Field. “St. Philip’s Is 85 Years Old.” The Atlanta Journal Magazine, October 30, 1932, p. 3. ↩︎

- The (Limited) Destruction of Atlanta – Emerging Civil War ↩︎

- Atlanta in the American Civil War – Wikipedia ↩︎

- “First Episcopal Church in Atlanta”. The Atlanta Journal, July 29, 1923, p. 9. ↩︎

- Perkerson, Medora Field. “St. Philip’s Is 85 Years Old.” The Atlanta Journal Magazine, October 30, 1932, p. 3. ↩︎

- “The New St. Philip’s Church.” The Atlanta Constitution, December 19, 1880, p. 1. ↩︎

- “St. Philip’s New Church.” The Atlanta Constitution, October 15, 1882, p. 11. ↩︎

- “St. Philip’s Cathedral Plans New Peachtree Road Building”. The Atlanta Constitution, May 15, 1933, p. 1. ↩︎

- “St. Philip’s Pro-Cathedral Will Be Dedicated Sunday, With Bishop Miskell Here”. The Atlanta Journal, September 9, 1933, p. 9. ↩︎

- Insurance maps, Atlanta, Georgia, 1911 / published by the Sanborn Map Company ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1899) ↩︎

- Norrman, G.L. Architecture As Illustrative of Religious Belief and as a Means of Tracing Civilization (1898) ↩︎

- “Home of Atlanta’s Fourth High School”. The Atlanta Journal, October 9, 1910, p. H 5. ↩︎

- “Church Sues City For $20,000 Damages”. The Atlanta Constitution, June 26, 1909, p. 6. ↩︎

- “Girls’ Business School Makes Stride Forward”. The Atlanta Journal, September 25, 1910, p. H 8. ↩︎

- “St. Philip’s Deanery Will Be School Soon”. The Atlanta Constitution, October 1, 1910, p. 12. ↩︎

- “Need Is Imperative For New High School House”. The Atlanta Journal, January 17, 1913, p. 14. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Old Crew St. School Will Be Used Again”. The Atlanta Constitution, July 31, 1913, p. 8. ↩︎

- “St. Philip’s Will Have Church School”. The Atlanta Journal, March 12, 1916, p. 7. ↩︎

- “The Ladies Aid of St. Philip’s Cathedral”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 21, 1917, p. 8. ↩︎

- “Cornerstone of Old St. Philip’s Will Be Removed to New Church.” The Atlanta Constitution, November 16, 1935, p. 3. ↩︎

- “St. Philip’s Cornerstone Opened”. The Atlanta Journal, November 24, 1935, Rotogravure Section. ↩︎

- “Agriculture Building To Be Occupied Soon”. The Atlanta Constitution, October 17, 1955, p. 20. ↩︎

- “St. Philip’s New Deanery In Course of Construction”. The Atlanta Journal, September 26, 1898, p. 6. ↩︎

-

Old Friends

Tim Tingle. Tree carvings at Orr Park. Montevallo, Alabama.

To hear these old friends of mine talk, you’d think there was something in the water that night.

Well, I’m here to tell you it wasn’t like that.

The place was an unholy mess, and no one was doing a damn thing about it.

Sometimes you just gotta take matters into your own hands and carve your own niche.

Can’t nobody else do it for you.

-

Empire Building (1909) – Birmingham, Alabama

Warren & Welton with Carpenter & Blair. Empire Building (1909). Birmingham, Alabama.1 2 3 References

- “All Plans Completed for Empire Skyscraper”. The Age-Herald (Birmingham, Alabama), May 12, 1908, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Outsiders Note City’s Growth”. The Birmingham News (Birmingham, Alabama), June 19, 1909, p. 22. ↩︎

- “Empire Ready Next Thursday”. The Birmingham News (Birmingham, Alabama), September 17, 1909, p. 3. ↩︎

-

“Journal Model Houses; Mr. J.B. Hightower’s New Home” (1898)

The Background

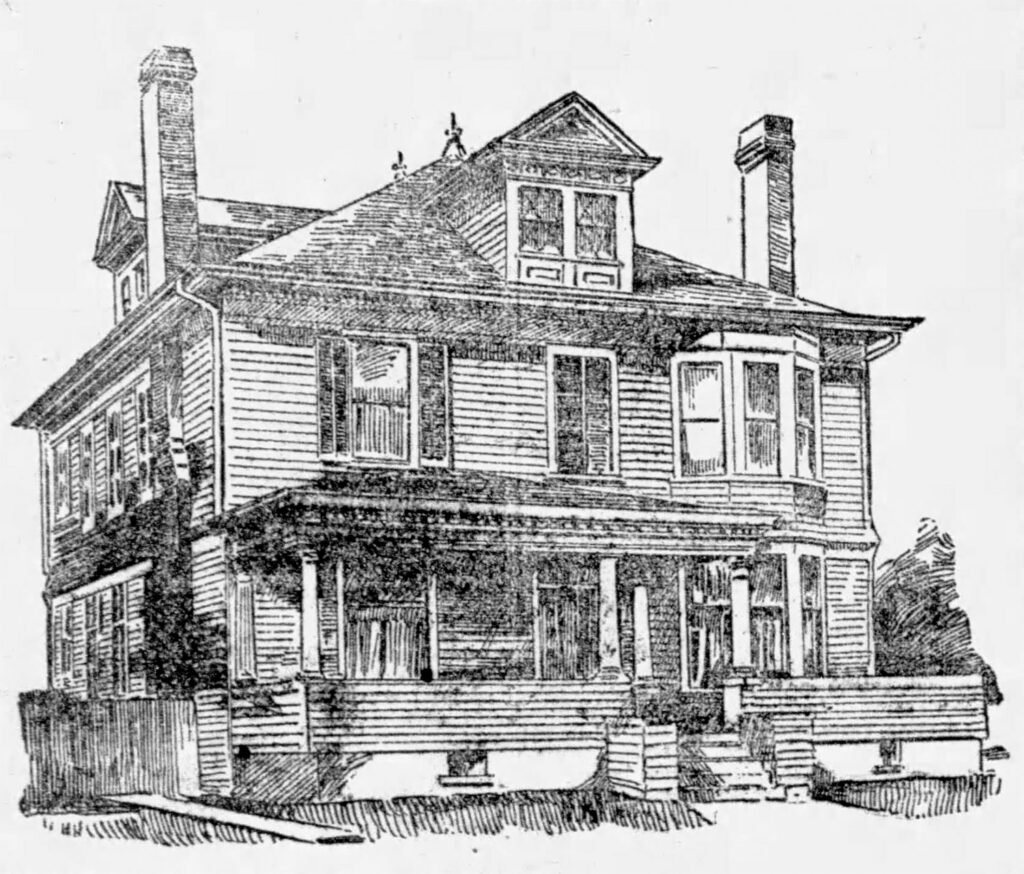

This is the final installment in a series of articles published by The Atlanta Journal in 1898 featuring illustrations and floor plans of residences designed by Atlanta architects — or, in this case, a contractor.

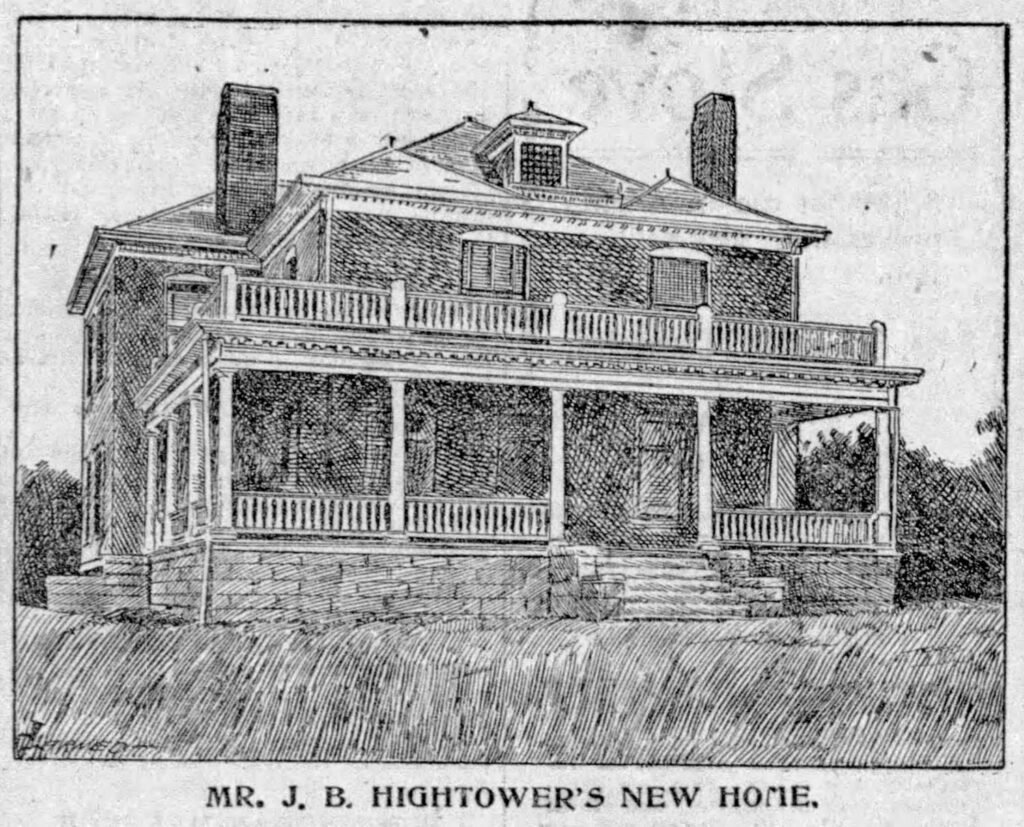

The Journal was clearly scraping the bottom of the barrel here, unless the intent was to caution readers against hiring an illegitimate architect. The article highlighted the J.B. Hightower Residence, located at 55 Hurt Street1 in Atlanta’s Inman Park neighborhood, and “done” by a local contractor, E.T. Gibbs.

Based on the illustration (pictured above), the home’s exterior was an artless mess: plain, boxy, and brick veneered with crude Colonial ornamentation tacked on, misaligned doors and windows on the front, and a mismatched roof topped by 3 tented peaks and an undersized dormer.

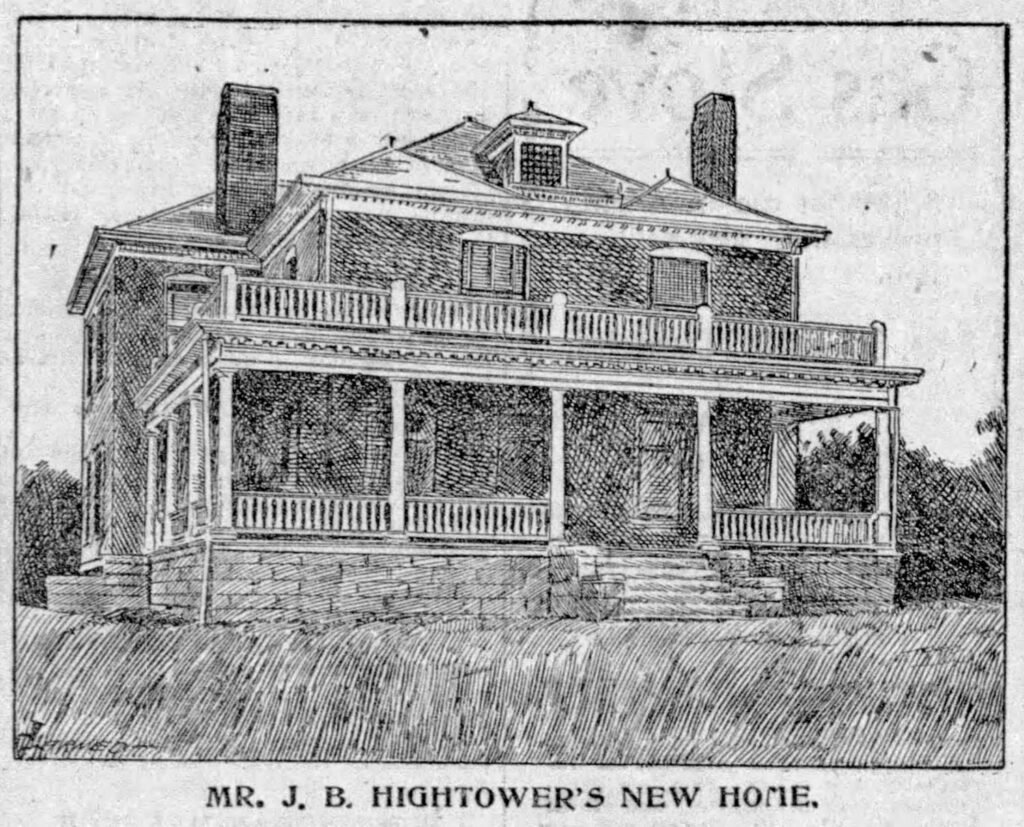

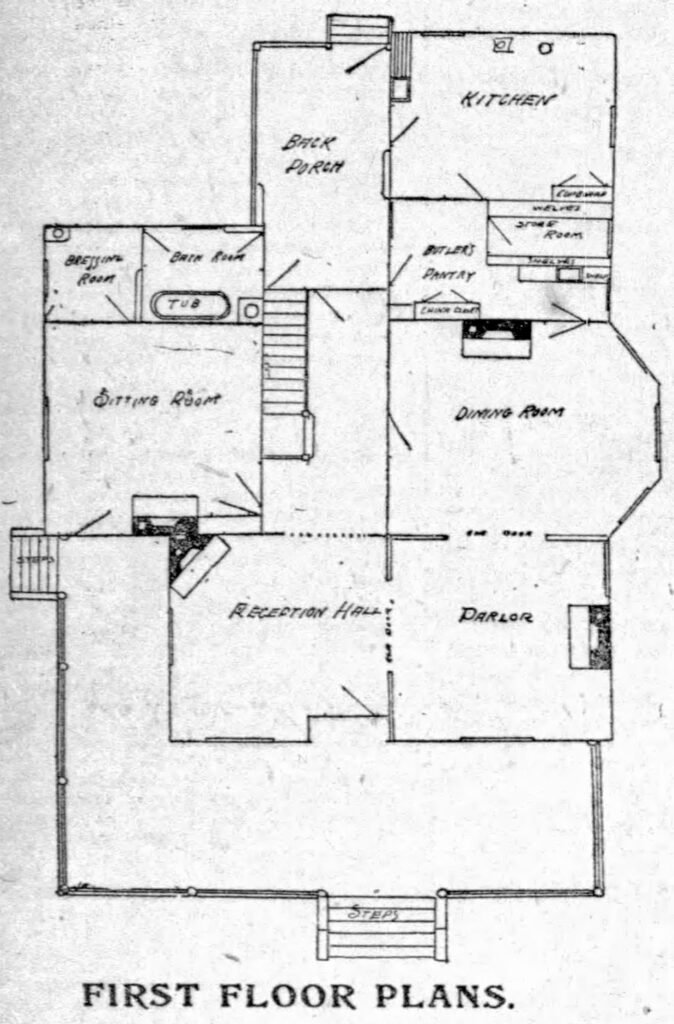

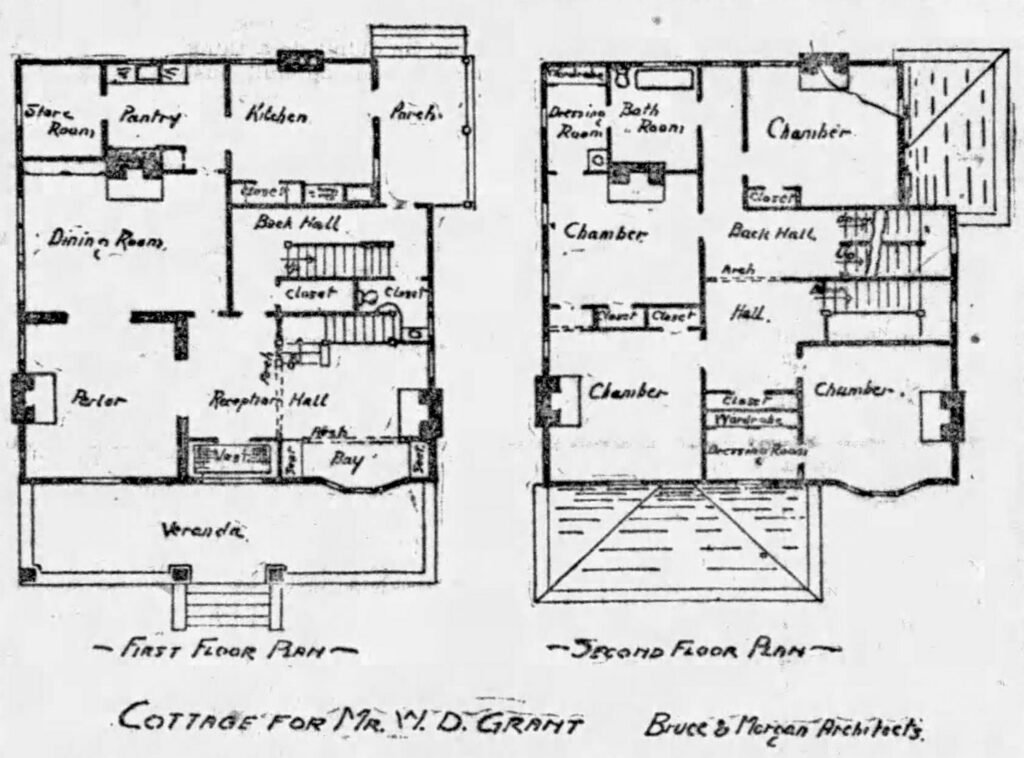

The crudely drawn floor plans (pictured below) are equally baffling and raise multiple questions about the home’s design.

Why, for instance, did the downstairs bathroom have a door to the back porch? Was it really necessary to give the upstairs hall and front left bedroom such awkward shapes to accommodate entry to the front right bedroom? And what the hell was the tiny “lunch room” sandwiched between the 2 floors?

Gibbs was no architect, and it’s likely that he simply swiped a plan from some pattern book and modified it (badly). He was also a notorious asshole.

In November 1909, Gibbs was arrested for assaulting his 17-year-old son in the street, with both of his sons testifying in court that he was “insane”. The trial revealed that Gibbs’s sons objected to his recent marriage to a much younger woman, 10 years after he separated from his first wife.2

Two months later, Gibbs’ young wife sued him for disorderly conduct,3 4 then filed for divorce, citing “his constant threatening, his striking her and his threats to strike her again”.5 6 Among the allegations, the newspapers focused on one in particular: that Gibbs had locked his wife out of their bedroom for placing her cold feet against him, forcing her to sleep in the servant’s room.7 8 9

Mrs. Gibbs said of her husband in a public statement: “He charges me with a great many things, and none of them are true, except that sometimes my feet are cold at night. I do not think this is a crime.”10 She was granted the divorce in April 1910 and awarded $25 per month for alimony.11

In July 1911, Gibbs was sued by his neighbor, Mrs. J. N. Norris, for threatening to “beat her in the face until she couldn’t bat her eyes.”12 Later that year, Gibbs began building an 18-foot-high “spite fence” between their 2 houses, prompting another lawsuit and a court injunction.13 14

During the trial in April 1912, Gibbs — who fired his lawyer and represented himself– was jailed 5 days for contempt of court after declaring all lawyers as “liars, rascals and thieves” and telling the judge: “I don’t give a damn what you do.”15 16

In late 1914, Gibbs was married to his third wife when he bought a pair of shoes from his estranged son’s shoe store, charging them to his son. When his son refused to accept the charge, Gibbs went to the store and angrily confronted him, throwing the shoes at his head.17

In court, Gibbs launched into a tirade on the witness stand, threatening violence against his entire family, and shaking his fist at an attorney, telling him: “I’ll knock you down in a minute if you call me a liar.”18

The spectacle landed Gibbs in jail again,19 20 with a trial held later that month to determine if he was insane.21 The jury determined he was “mentally normal”, based on the testimony of “a number of women” who cited his “honesty in business and personal dealings”.22

Based on the plans here, I can also testify: Gibbs was an honestly terrible excuse for an architect.

In 1901, the house at 55 Hurt Street (later 161 Hurt Street NE) was already occupied by a different owner, Robert K. King,23 24 and by 1927, it was being marketed as (what else?) a boarding house.25 It appears to have been demolished for a 4-story educational building for Inman Park Baptist Church, which completed construction at the address in 1955.26 27

The church sold its property to the state of Georgia in 196728 for the construction of the planned I-485 freeway, with all structures on the east side of Hurt Street demolished for the project. The proposed interstate was officially killed in 1975 after widespread local protest and opposition from the mayor and city council.29 Today, the land is part of Freedom Park.

Journal Model Houses; Mr. J.B. Hightower’s New Home

Mr. J.B. Hightower has just completed a $4,000 residence in Inman Park, and it is one of the most attractive homes in the city. The house is a good type of a combination wood and brick residence. It is claimed that is construction is better in some ways than walls entirely of brick, though it costs less.

The foundation is of stone in front and brick elsewhere. The veranda is 12 feet wide, with an ample vestibule. The reception hall, parlor and diningroom [sic] are furnished in oak, and the other rooms in oiled pine, excepting the kitchen and pantry, which are grained to represent oak. The principal rooms have plate glass windows and the walls are finished with neat picture mold. The plumbing and electrical connections are first class and adjusted in the most convenient manner.

The premises are provided with a barn, carriage house and servants’ quarters, and everything is completed in good style, with first class workmanship. The work was done by Mr. E.T. Gibbs, contractor and architect.30

References

- ↩︎

- “Father Was Fined For Striking Son”. The Atlanta Journal, November 15, 1909, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Contractor E.T. Gibbs Accused By His Wife”. The Atlanta Journal, January 29, 1910, p. 4 L. ↩︎

- “Says Drink And Novels Made Home Very Unhappy”. The Atlanta Journal, January 31, 1910, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Wife Files Divorce Against E.T. Gibbs”. The Atlanta Journal, February 5, 1910, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Mrs. Gibbs Brings Suit For Divorce”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 6, 1910, p. 6. ↩︎

- “Says Drink And Novels Made Home Very Unhappy”. The Atlanta Journal, January 31, 1910, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Not A Crime To Have Cold Feet, Says Woman”. The Atlanta Journal, February 1, 1910, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Read Novels At Night Until She Got Cold Feet”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 1, 1910, p. 4. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Wife Gets Divorce And Small Alimony”. The Atlanta Journal, April 9, 1910, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Rebuked By Neighbor For Punishing Child”. The Atlanta Constitution, July 16, 1911, p. 3. ↩︎

- ‘”Spite” Fence 18 Feet High Causes Suit For Injunction’. The Atlanta Constitution, December 21, 1911, p. 8. ↩︎

- ‘Seeks To Stop “Spite” Fence’. The Atlanta Constitution, December 22, 1911, p. 13. ↩︎

- “Acting As Attorney, Gibbs Abuses Lawyers”. The Atlanta Journal, April 30, 1912, p. 28. ↩︎

- “Kicks Up Rumpus In Court, Is Sent To Jail”. The Macon Telegraph (Macon, Georgia), May 1, 1912, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Contractor In Court, Hurls Abuse At Family”. The Atlanta Journal, November 5, 1914, p. 1. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Father Sent To Jail At Instance Of Son”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 6, 1914, p. 10. ↩︎

- “Is Contractor Crazy?” The Columbus Ledger (Columbus, Georgia), November 24, 1914, p. 4. ↩︎

- “Man’s Honesty Is Proof Of Mental Soundness”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 24, 1914, p. 4. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1901) ↩︎

- “C.S. King Dies Suddenly Today Of Heart Failure”. The Atlanta Journal, June 17, 1902, p. 7. ↩︎

- “Rentals”. The Atlanta Journal, August 24, 1927, p. 29. ↩︎

- “Inman Park Pastor Ending Third Year”. The Atlanta Journal, April 9, 1955, p. 4. ↩︎

- Barre, Laura. “Inman Park Baptists To Dedicate Building”. The Atlanta Journal, December 10, 1955, p. 10. ↩︎

- “Inman Park Baptists Will Hold Homecoming”. The Atlanta Journal, August 12, 1967, p. 6. ↩︎

- Nordan, David. “FHA Sounds Death Knell For Ballhooed I-485”. The Atlanta Journal, April 22, 1975, p. 6-A. ↩︎

- “Journal Model Houses; Mr. J.B. Hightower’s New Home”. The Atlanta Journal, June 11, 1898, p. 8. ↩︎

-

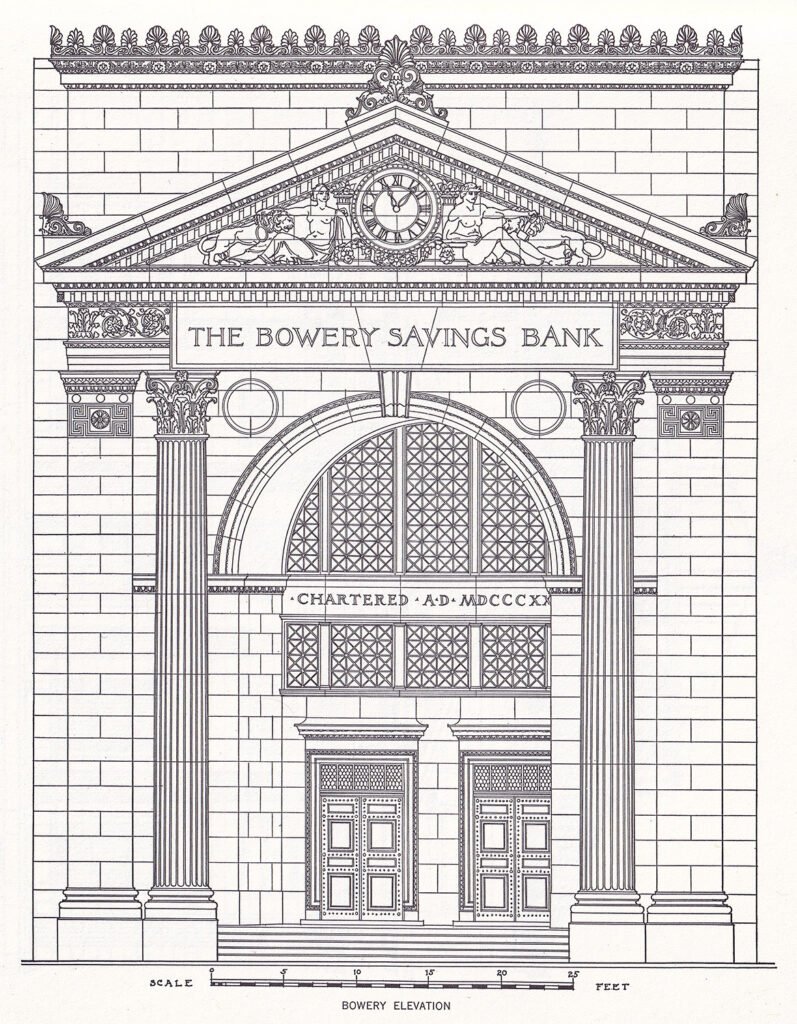

Bowery Savings Bank (1895) – New York

Stanford White of McKim, Mead & White. Bowery Savings Bank (1895). New York.1 2 3 4 5 6 The Bowery Savings Bank is a significant early work in the Classical Revival style, credited to Stanford White of McKim, Mead & White.

Following their monumental buildings of classical inspiration for the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, the firm entirely embraced Roman and Renaissance influence in their designs, ushering in the Beaux Arts movement that dominated American architecture for decades.

By the time of White’s death in 1906, the firm’s work had become increasingly derivative and dreary, but this structure was designed early enough to retain some of their initial flair for quirkiness and originality: the front doors set slightly off-center within a recessed arch, for instance.

Built in the shape of an L with granite and Indiana limestone, the Bowery Savings Bank has two entrances, neither of which resembles the other — a larger side entrance on Grand Street, and the smaller, more interesting Bowery side shown here.

It appears the building was largely designed by Edward P. York, then White’s assistant, who also supervised its construction. York would later become a founding partner in the architectural firm of York & Sawyer.7

Ever the playboy, in the mid to late 1890s, White increasingly delegated his work to others while he indulged in a lavish lifestyle of excess and consumption — it didn’t end well for him.

Elevation8

References

- A Monograph of the Work of McKim, Mead & White 1879-1915, Volume 1. New York: The Architectural Book Publishing Co. (1915). ↩︎

- “The Bowery Savings Bank’s New Building.” New-York Daily Tribune, February 14, 1893, p. 11. ↩︎

- “Another Handsome Bank Building.” New-York Daily Tribune, February 15, 1893, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Financial Announcements.” The New-York Times, June 24, 1894, p. 14. ↩︎

- “Bowery Bank’s New Building.” The World (New York), June 27, 1894, p. 6. ↩︎

- “Bowery Savings Opens New Home”. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (New York), June 22, 1923, p. 22. ↩︎

- Bowery Savings Bank Building – Landmarks Preservation Commission ↩︎

- A Monograph of the Work of McKim, Mead & White 1879-1915, Volume 1. New York: The Architectural Book Publishing Co. (1915). ↩︎

-

“Journal Model Houses; One of Captain Grant’s Cottages” (1898)

The Background

This is the eighth in a series of articles published by The Atlanta Journal in 1898 featuring illustrations and floor plans of residences designed by Atlanta architects.

Here, the Journal highlighted a “model cottage” owned by W.D. Grant and designed by Bruce & Morgan. Grant was one of Atlanta’s wealthiest citizens, having amassed a fortune in railroad building before becoming a local real estate tycoon.1

He was also a longtime client of Bruce & Morgan, and the firm designed multiple projects for Grant’s family and companies, starting with a block of stores in 18822 and culminating in 1899 with one of Atlanta’s first skyscrapers — the 10-story Grant Building3 — which still stands.

The 2-story cottage shown here was much more modest in scope, but one of 7 apparently identical residences that Grant commissioned the firm to design for various locations around the city, presumably as rental properties.

The home’s appearance was a simple but attractive expression of the Colonial style, with classical columns, dentilled cornices, a stringcourse between the floors, and a hip roof topped with dormer windows and decorative finials.

The floor plan was based on a simple 4-square grid and managed to pack in a reception hall, parlor, dining room, kitchen, 3 bedrooms, one full bath on the second floor, and a half-bath on the ground floor.

A few interesting aspects of the plan are the front and back stairs separated by a shared wall, the lavatory tucked beneath the back stairs — also seen in the plan for the James F. Meegan Residence — and the built-in seating and shelves in the reception hall.

The design fits in well with Bruce & Morgan’s other work: never especially exciting or innovative, but consistently thoughtful and competently executed, particularly given the partners’ lack of formal training.

Based on the location details provided in the article, none of the 7 cottages from this plan survives.

Journal Model Houses; One of Captain Grant’s Cottages

The accompanying illustration and plans show the exterior appearance and reveal the interior arrangement of a model cottage, which is one of a number recently constructed by Captain W.D. Grant. The plans were drawn by Bruce & Morgan. The cost to construct and fit out with mantels, tiling, plumbing, etc., was $3,500.

Captain Grant built five of the cottages on Piedmont avenue, one on Currier street, and now has another in process of erection on Courtland near Pine.

The exterior presents a well proportioned and substantial building, which is nevertheless attractive in its architectural effect.

The first floor has a spacious veranda connected by a vestibule with the reception hall.

The second story has four bed chambers, dressing rooms, closets and a bath room.

The fixtures, as well as the architectural style, are of the most improved plain. The plumbing is of the best, while the handsome mantels, tiling and stained glass windows add much to the beauty of the residence. The house provided with both gas and electric lights.

The plans will be received with favor by those who are contemplating building houses.4

References

- “Funeral of Captain Grant To Occur This Afternoon”. The Atlanta Constitution, November 8, 1901, p. 5. ↩︎

- “Architecture.” The Atlanta Constitution, September 23, 1882, p. 9. ↩︎

- “Georgia Marble in the Prudential”. The Atlanta Journal, May 10, 1899, p. 10. ↩︎

- “Journal Model Houses; One of Captain Grant’s Cottages”. The Atlanta Journal, April 23, 1898, p. 4. ↩︎

-

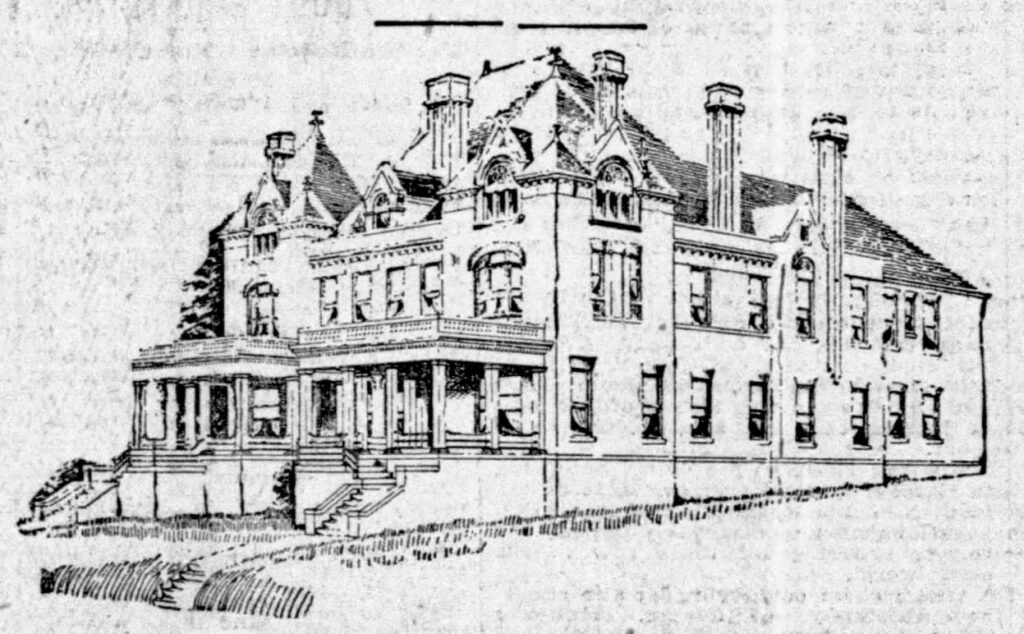

“Captain William H. Brotherton’s New Whitehall Street House” (1898)

The Background

This is the seventh in a series of articles published by The Atlanta Journal in 1898 featuring illustrations and floor plans of residences designed by Atlanta architects.

The article highlights a double apartment house owned by W.H. Brotherton and designed by Butt & Morris.

Tenement houses of this type were ubiquitous in Atlanta at the time, and were the immediate forerunners to the larger “apartment houses” that began appearing in the city at the turn of the 20th century.

Like the so-called “luxury” apartments of today, these homes were designed for image-conscious people of limited means who aspired to the appearance of wealth — that could easily describe half of Atlanta. No one was fooled by the conceit, of course, and despite a few “elegant” flourishes, the structures inevitably looked like crass, downscale imitations of costlier designs.

Only a ground floor plan was published with the article, but it reveals a fairly straightforward design, with each unit containing a parlor, library, dining room, and kitchen on the first level, and a separate reception hall and stair hall.

The plan included a “complete bath-room on each floor”, along with a small butler’s pantry and rear service stairs — the people who lived in such homes could usually only afford one or two servants.

Built of pressed brick with granite trim, the appearance of the duplex was akin to Butt & Morris’s only significant work remaining in Atlanta: the George A. Floding House in Inman Park, built in 1907.1 2 Both designs are similarly atrocious.

Butt & Morris. George A. Floding House (1907). Inman Park, Atlanta. Based on a vague location described in the building permit and the details provided in this article, it appears the Brotherton apartments were located at 382 and 384 Whitehall Street, on the southeast corner of Whitehall and Hood Street.3

The structure predictably became a boarding house in fairly short order,4 and was demolished in July 1927,5 replaced by — wait for it — a gas station.6

Captain William H. Brotherton’s New Whitehall Street House

The above cut is an exact likeness of the new apartment house built by Mr. W. H. Brotherton on Whitehall street, between Windsor and Smith streets, upon which the finishing touches are now being applied.

The dwelling is a beauty in its style of architecture and is palatial in its appointments. It was built at a cost of $9,000.

It is a tenement house, consisting of ten rooms and spacious hall on each side. Besides the main rooms there are bath, linen and dressing rooms.

The exterior is built of pressed brick, with granite trimmings. The roof is of the very best slate. The verandas are very long, with a width of about 20 feet. Immense columns, built of pressed brick with granite capitols, support the roofs of the verandas. The ceiling of the verandas are of stamped iron, while the floors are of tile. The verandas are also fitted with beautiful iron balustrades.

The main front entrance is through an open vestibule, artistically panneled [sic] in oak. This leads into a large reception hall. The reception room, stair hall, reception hall and dining room are finished with 4 1/2-inch panneled [sic] wainscoting, with other decorations of modern design. These apartments, together with front and back parlors, make five apartments in all. They are conveniently connected with sliding doors. The passage from the dining room into the large, well arranged kitchen is through double swing doors. The back hall is conveniently reached from the front stair hall, kitchen or rear portches [sic]. The halls, pantries and bathrooms are wainscoted. The flooring is of the best grade.

The second floor consists of five large, well light [sic] chambers, with closets in easy reach. All the rooms but the kitchen are fitted with beautiful oak mantels with large plate glass. The hearths are built of tile. The plumbing fixtures are elegant in every respect. There is a complete bath-room on each floor, with all the modern appliances.

The plastering is three-coat finished in sand, and all the walls are beautifully tinted in delicate colors. The glass is first quality.7

References

- Application for Building Permit, September 20, 1907 ↩︎

- “Social Items”. The Atlanta Constitution, October 6, 1907, p. 4. ↩︎

- Insurance maps, Atlanta, Georgia, 1911 / published by the Sanborn Map Company ↩︎

- “Wanted — Boarders”. The Atlanta Journal, December 29, 1912, p. 11. ↩︎

- “Building Materials”. The Atlanta Constitution, July 3, 1927, p. 1C. ↩︎

- “Commercial Locations Still in Active Demand, Ewing Agency Reports”. The Atlanta Journal, July 24, 1927, p. 8D. ↩︎

- “Captain William H. Brotherton’s New Whitehall Street House”. The Atlanta Journal, March 19, 1898, p. 6. ↩︎

-

Piedmont Natives: Gulf Fritillary

Gulf fritillary butterfly (Agraulis vanillae) Here’s a fine fall friend I recently met on the Atlanta BeltLine. Hooray for public arboretums!