The Background

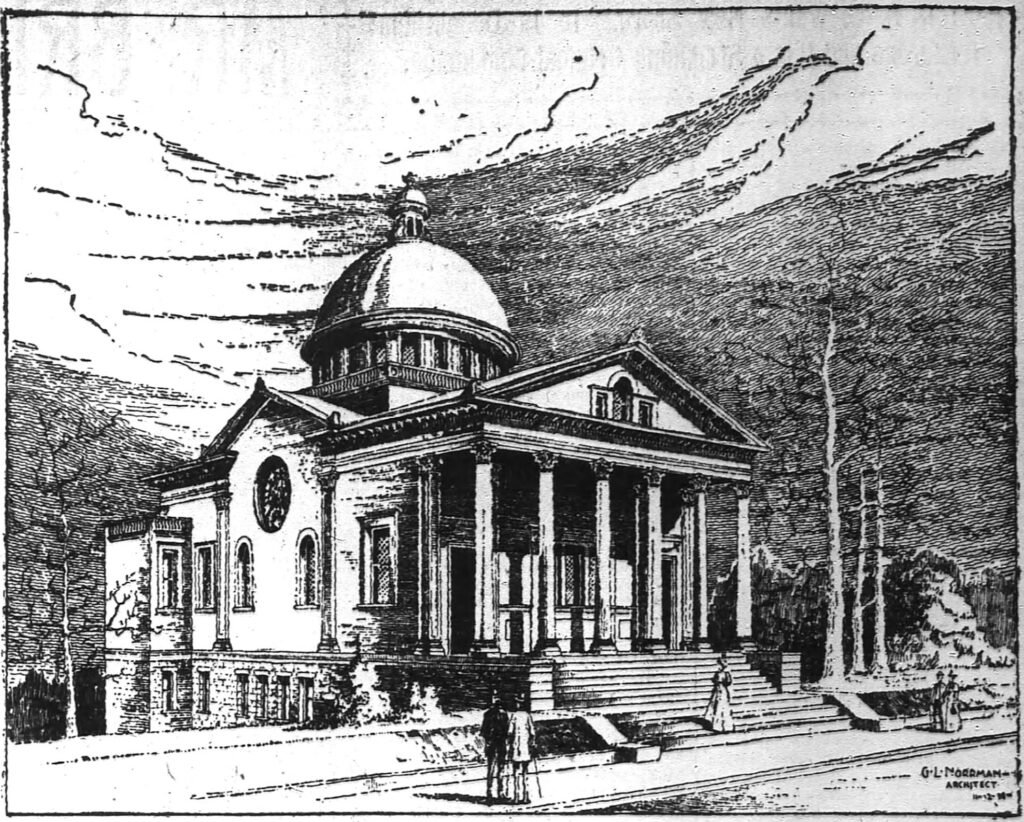

G.L. Norrman was a man of forceful and contrary opinions that often riled the ruling class of Atlanta, a pretentious pack of lying dullards who couldn’t face the truth if their lives depended on it.

What no doubt baffled them the most about Norrman was that he could fully articulate his objections in a defined and intelligent manner, of which most people are simply incapable.

In February 1899, the Atlanta Concert Association hosted a concert at Degive’s Grand Opera House by the Polish pianist Moriz Rosenthal, who was popularly referred to by his last name only.1

Rosenthal was internationally famous, and his appearance in a backwater like Atlanta was considered a cultural milestone for the city.

The newspapers were expectedly fawning of Rosenthal’s performance, but a reporter from The Atlanta Journal got an earful when he asked Norrman for his thoughts on Rosenthal, which were published on February 17, 1899, in the “Loitering in the Lobbies” column.

The comments include multiple references to 19th-century performers, and appropriate informational links have been provided. However, there is scant information online about Joseph Denck (1848-1916), a pianist from Columbia, South Carolina who primarily performed in the Southeast.

Norrman’s remarks:

“Yes, I heard Rosenthal, and while I do not profess to be a musical critic I don’t mind saying how he impressed me.

“I think his technique was very good—but that his selections were poor. I am backed up by an Atlanta musician who is far above the average, in fact, almost a professional. You see, Rosenthal played last night nothing that is familiar even to the average musician much less the great body of his audience. Indeed, as a popular success his entertainment was a dead failure. Now, if he had played a few selections even from such composers as Rossini, Beethoven, Wagner, I could have followed him much better. But, as it was, I could hardly follow him at all—and, of course, the great body of his auditors could not enjoy his playing.

“It would have been far better if he had played selections from composers more familiar to people of average musical culture and thrown in popular airs for the benefit of the great majority of his audience who could have understood them. As it was these people simply sat there got nothing for their money.

“Perhaps there were a dozen or so persons in the audience who really enjoyed the performance. Still I couldn’t prove even this. If the bringing of Rosenthal here was to arouse an interest in music and help the people to understand it, I can’t see exactly how this object was accomplished.

“Say, for instance, that the majority of his hearers were up in the multiplication table of music, so to express it, and I am satisfied that such was not the case—how could they even then be expected to make a long leap and understand and enjoy the calculus of music he undoubtedly gave. For his selections were all of the highest, the most difficult grade, ultra scientific and classical.

“So, in my view, his performance was not only a failure from a popular standpoint, and was not even a success judged from the plans of average and even above the average musicians and people of musical culture.

“For my own part, I much prefer Mr. Joseph Denck as he played a few years ago. He has a marvelous touch and always played selections from composers more or less familiar to music lovers, and his playing of popular music is exquisite. Yes, as Denck played a few years ago, when I last heard him. I like him better than Rosenthal. He is not only a wonderful pianist, but knows how to please the average musicians and the people better than Rosenthal, judged by his performance last night.”

Reporter: How does Rosenthal compare with Padarewski?

“He’s about as good, I think. I never thought Paderewski such a miracle of a musical genius as some people did. I saw nothing about him to lose my head over. He’s very fine, no doubt, but so is Rosenthal, I suppose—

“But admit that Rosenthal was as fine as fine can be Wednesday night. What does it amount to him if we cannot follow him?

“It is not good taste in a pianist to be ever so fine if his audience don’t know it—can’t take in his fineness. Just as it would not be good taste for a person to speak Greek in a parlor full of people if nobody present understood the language.

“I am no musical critic, but I try to take a common sense view of Rosenthal, and am backed up in what I have said by a musician of far more than average ability in musical matters. We were discussing Rosenthal after his performance and found that our views coincided concerning his recital.”2

References