The Background

In 1897, G.L. Norrman took a 4-month trip to Europe,1 2 returning to the continent for the first time since he emigrated to the United States in 1874. Naturally, The Atlanta Journal published an account of his observations in a December 9, 1897, article titled “Unique View of Old World”.

In speaking about England, Norrman references Lady Somerset, the leader of the British temperance movement, whom he accused of slumming, a distinctly 19th-century pastime in which the wealthy found it fashionable to tour the impoverished areas of cities to sate their morbid curiosities.

Norrman was appalled to find women invading England’s saloons, quoting Alexander Pope, the English poet, from his poem Essay on Man, Epistle II, for a warning on the dangers of “sentimentality”. Here, he also took the opportunity to comment on protective tariffs that had been imposed by the United States in 1897 — Norrman was not a supporter.

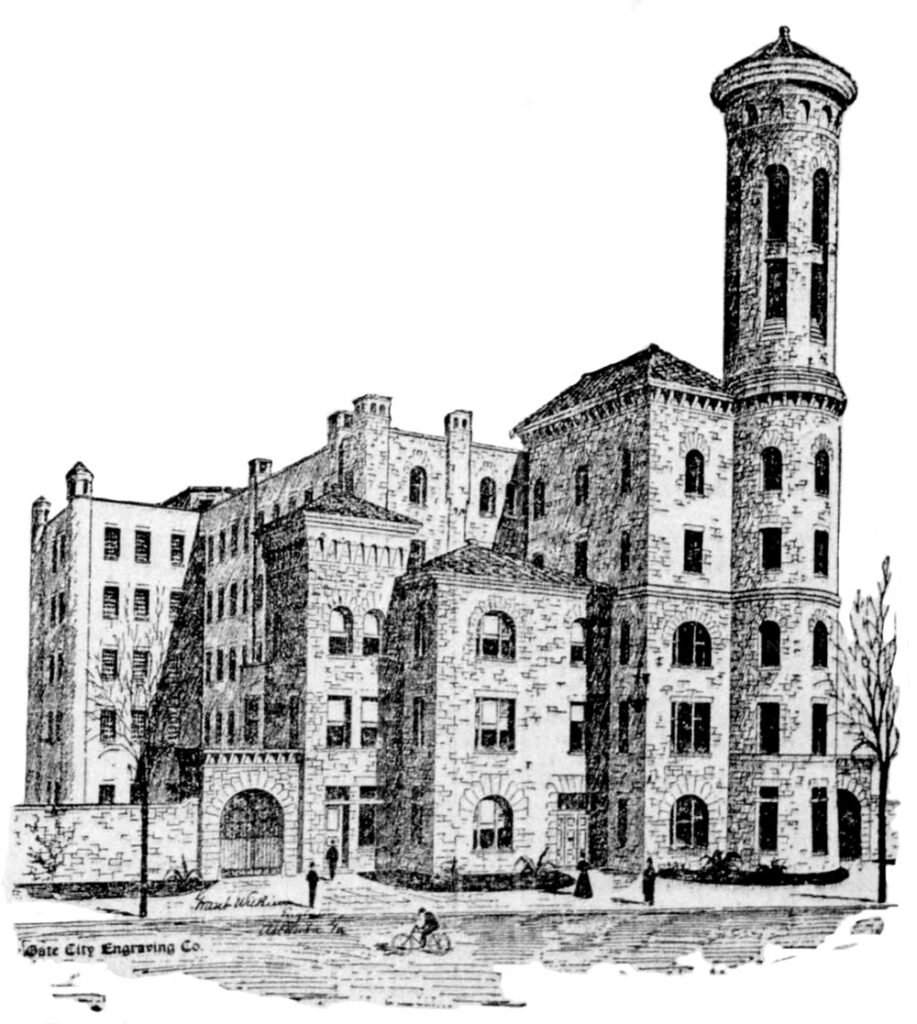

Norrman’s thoughts on European architecture and history (a characteristic quip: “a great deal of Roman history is merely romance”) were expounded on further in his 1898 pamphlet, Architecture as Illustrative of Religious Belief.

Norrman’s remarks:

“England, I could see, is not doing well. I was struck by existing conditions in London. There is more drunkenness there than in any other city I visited. In fact, I saw more drunkeness in England than in any other country. It seems that since Lady Sommerset [sic] has made slumming fashionable, all the women of England have gone slumming. I have seen more drunken women in England than in any other country. There they might sing the song, “Dear Mother, Come Home,” instead of “Dear Father, Come Home“. It is as common a sight to see women in saloons in London as it is to see men in our American saloons. I have often passed barrrooms and seen as many as half a dozen women standing at the counter. Twenty years ago, when I was in England, the common women of the worst streets seemed not as brazen as the well dressed women one sees on the principal streets today.

“Sentimentality is running rampant in England, and when sentimentality goes wild it does more harm than all the vices put together that human frailty is heir to.

“Vice is a monster of such frightful mein,

As to be hated needs but to be seen;

Yet seen too oft, familiar with her face,

We first endure, then pity, then embrace.”“Where there is no morality society begins to break down. In England disintegration of society is noticeable everywhere. There seems to be a feeling in the air there that the people are expecting something to turn up, they don’t know what.

“Their social system is based on hypocrisy and cant.

“I made considerable investigation along historical lines while in Europe, and am led to believe that a great deal of Roman history is merely romance. I base this opinion on the the fact that no picture of any kind, either painted, modeled or carved, can be found which illustrates any of the cruelties we read of. A people with slaves who were such great picture makers would surely have been put on record through the medium of their art, if the cruel practices of their masters had really occurred. I feel quite sure that if historians had understood architecture, ancient history would have read quite differently from what it does.

“In the transmission of history, language is very unreliable whenever metaphors are used. For instance, if in 2,000 years from now a newspaper should be found stating that the police commissioners had cut the head off of the chief, the reader would naturally think that there were very bloodthirsty police commissioners in those days.

“In making a study and investigation of ancient architecture I found that there are no crucifixes of any description before the fifth century. The earliest that can be found are in the Bysantin style and could not have been made before there was a Bysantin style, which was about 500 years after Christ is supposed to have lived.

“In business prosperity the countries of Europe seem to be doing well, with the exception of England, as I have already stated. There is a great deal of improvement going on in Italy. There is as much building going on in Rome as in New York. Many blocks of old Roman buildings are being torn down and fine boulevards are being laid out. All of the blocks of houses in front of St. Peter’s cathedral have been condmened and it is intended to open a large boulevard from the church to the river. This will give a splendid view of the cathedral. Hitherto it has been obscured by the many houses around it.

“The European countries seem to have the highest regard and admiration for the United States. I heard no adverse criticisms in regard to the policy of our government except in reference to the protective tariff. The people of Europe do not like this feature in our policy, and it is the occasion of considerable unfavorable comment among all the countries I visited. For my own part I think the protective tariff is a mistake. It produces an uncalled for antagonism, because from what I saw of American exhibits in Brussels, London and Stockholm, America can beat the world in all kinds of goods that are made by machinery in regard to both price and quantity. While it is true that European laborers do not get as much as American laborers it is also true that American laborers can do about three times as much as European laborers. I know that it is so in regard to building and I presume it is so in all other lines also. The cost of building per cubic foot is greater in Europe than here, notwithstanding that labor is much cheaper.

“There is a great deal of building going on in Vienna and Stockholm. The style of the architecture in these places I liked very much. The old German style of architecture in Vienna I found to show a high form of art. But I believe that I liked the Roman styles better than those of any other city or country that I visited.

“As to the result of my trip to Europe, it depends on from what standpoint it is viewed. In regard to keeping the rain out of a building, I have no new information, but as to the meaning of architecture, I have learned a good deal. I have especially given attention to the meaning of the forms used in Romanesque architecture.”3