The Background

This is the sixth in a series of articles published by The Atlanta Journal in 1898 featuring illustrations and floor plans of residences designed by Atlanta architects.

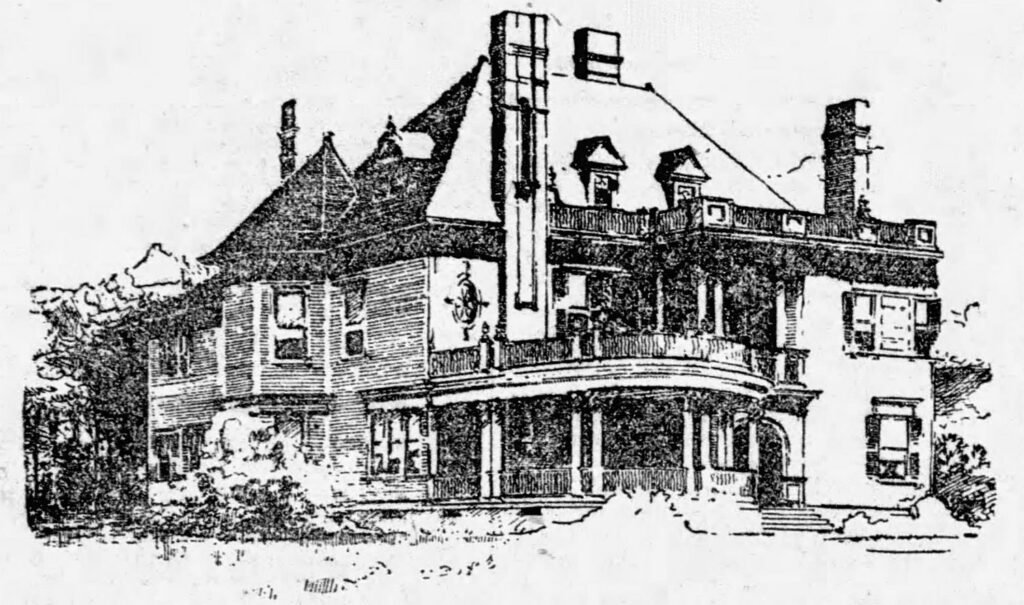

The article highlights the George Wade Residence, designed by C. Walter Smith, who served for many years as a draughtsman and later chief assistant to G.L. Norrman,1 2 before successfully establishing his own firm in 1896.3

The Wade home’s floor plan hints at how much Smith was responsible for designing Norrman’s residences — I suspect it was quite a bit.

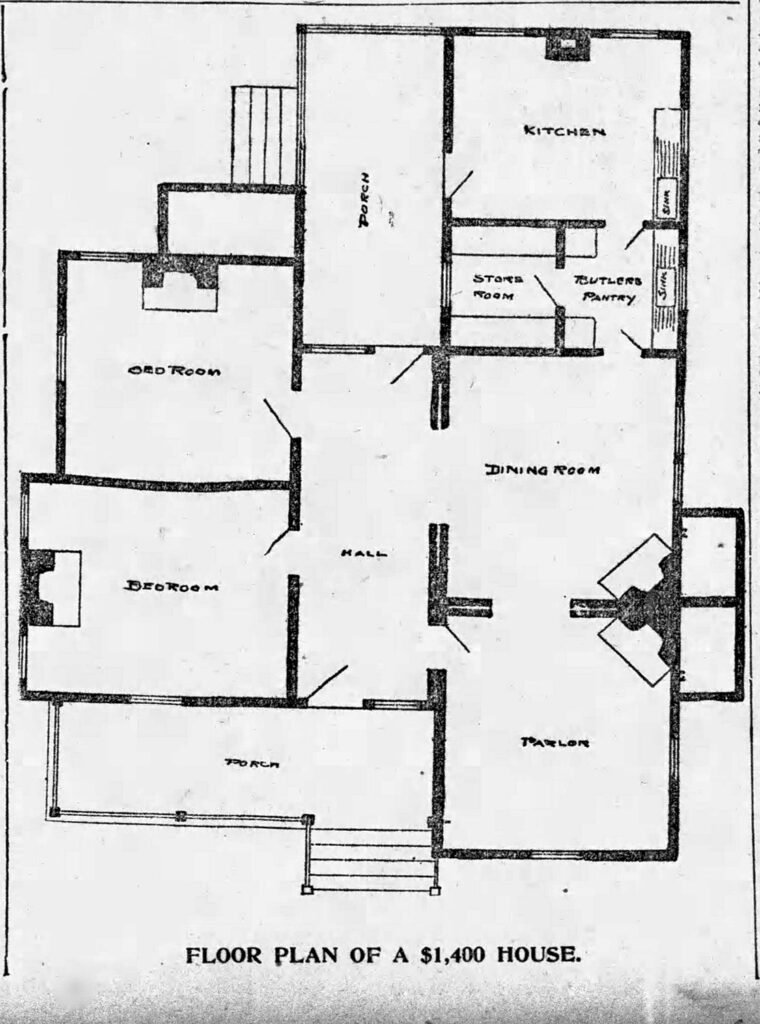

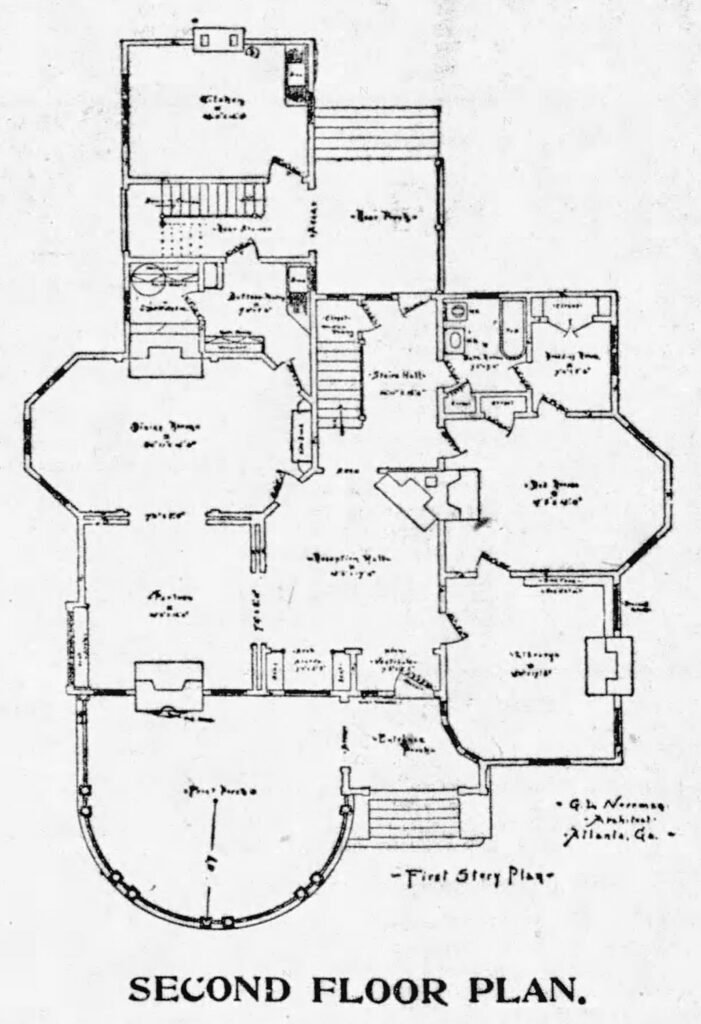

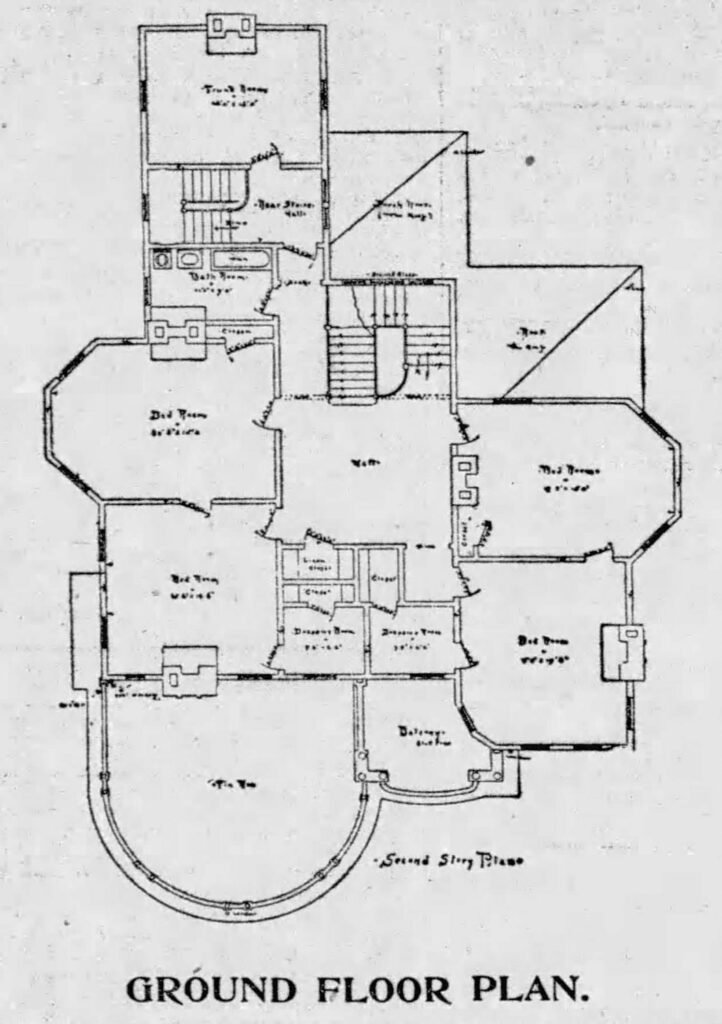

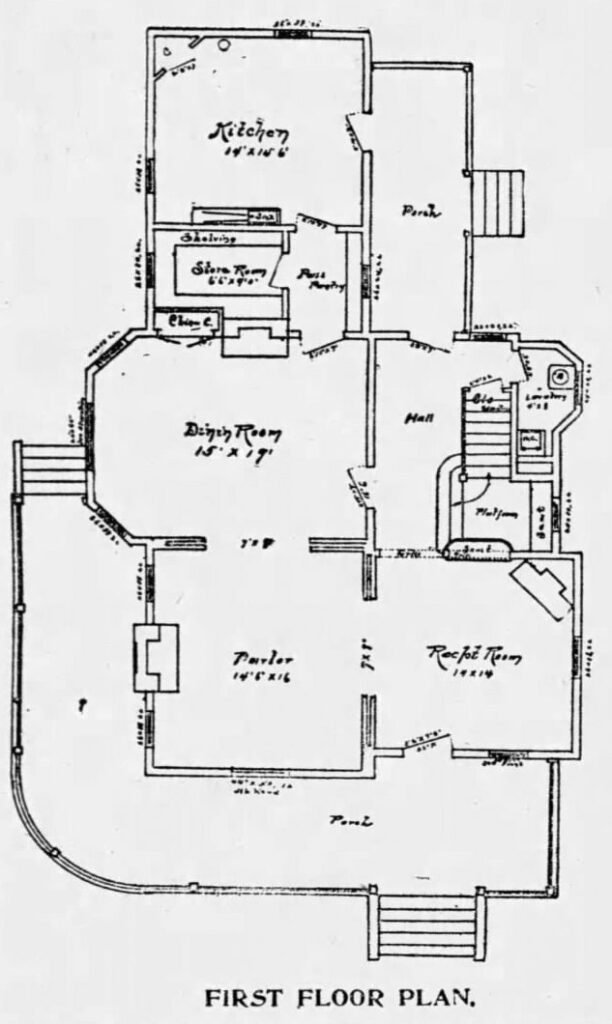

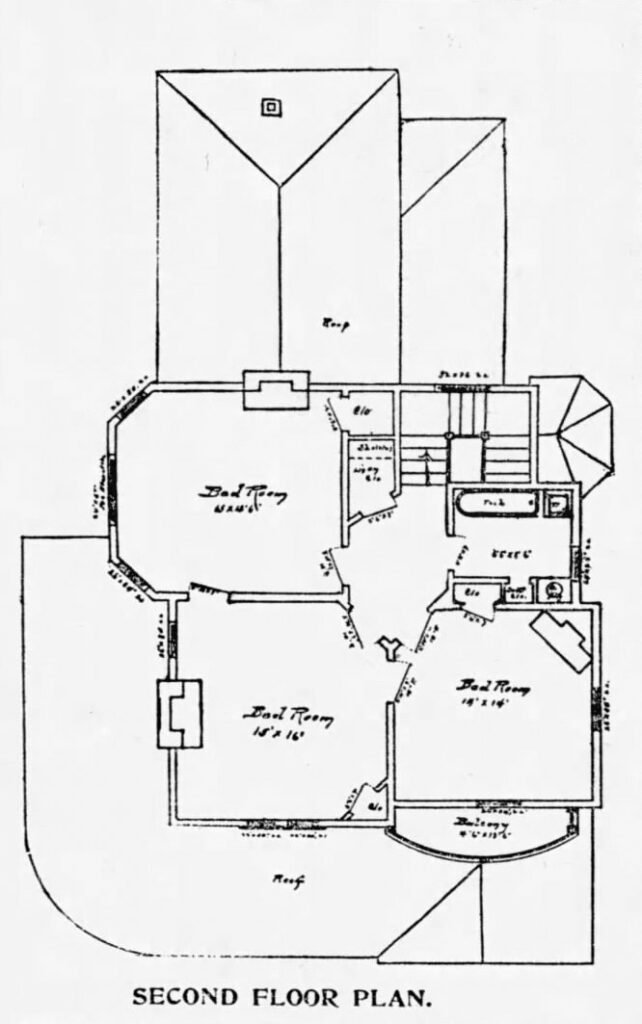

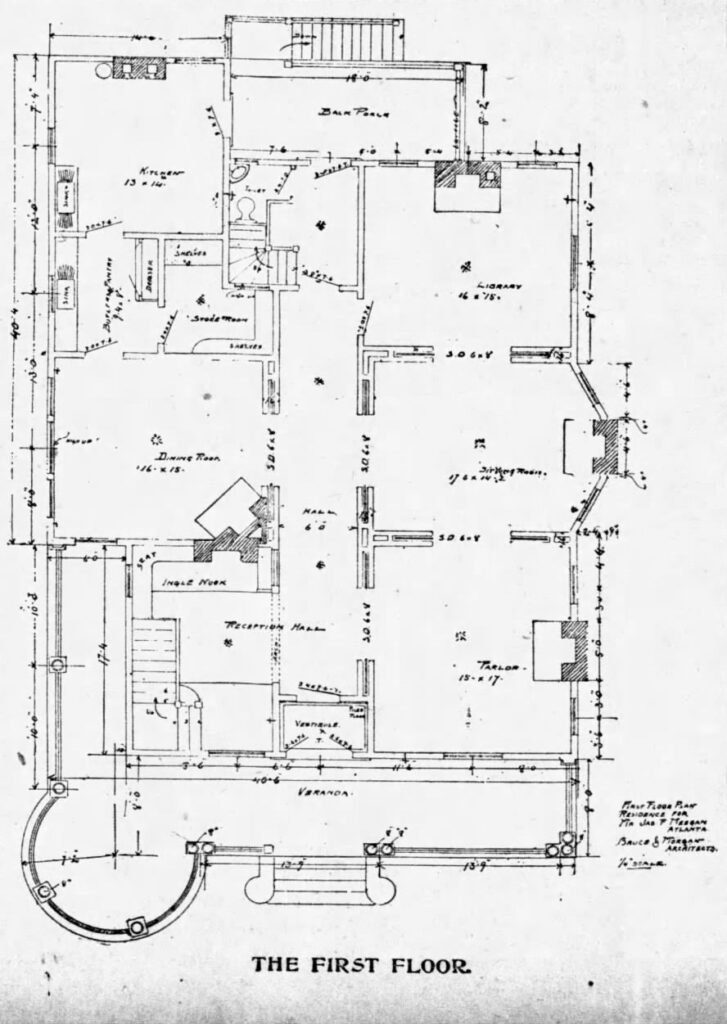

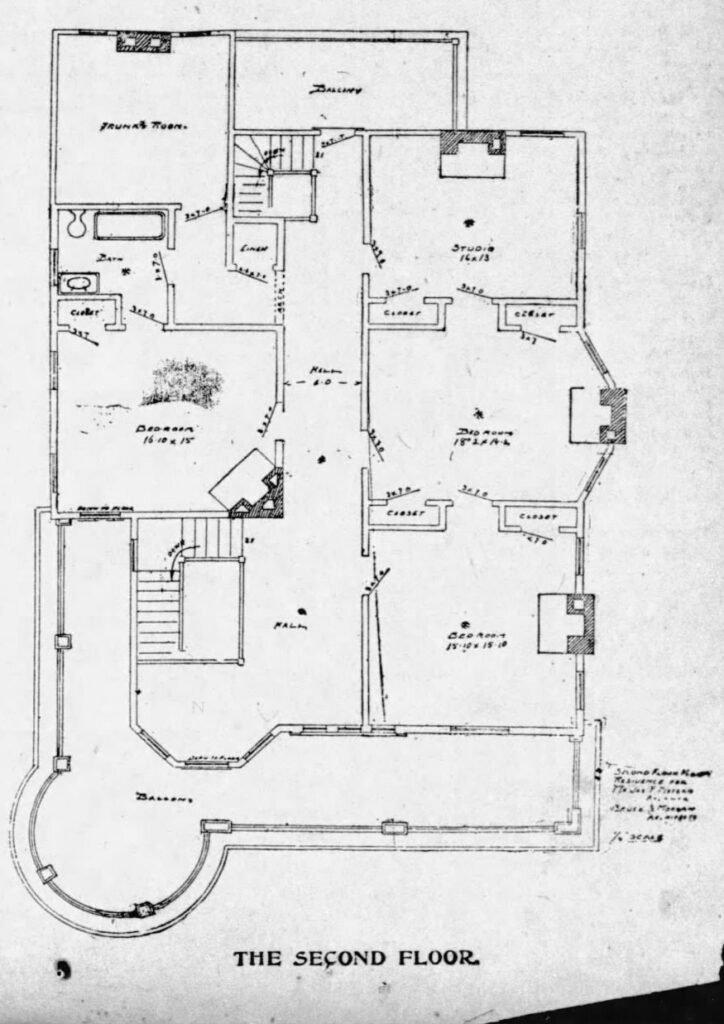

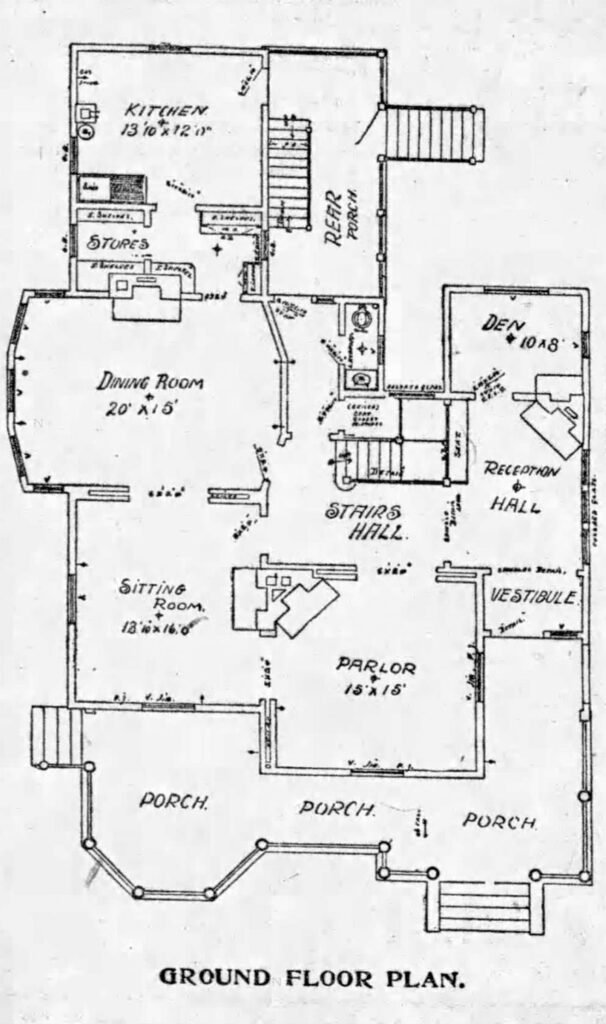

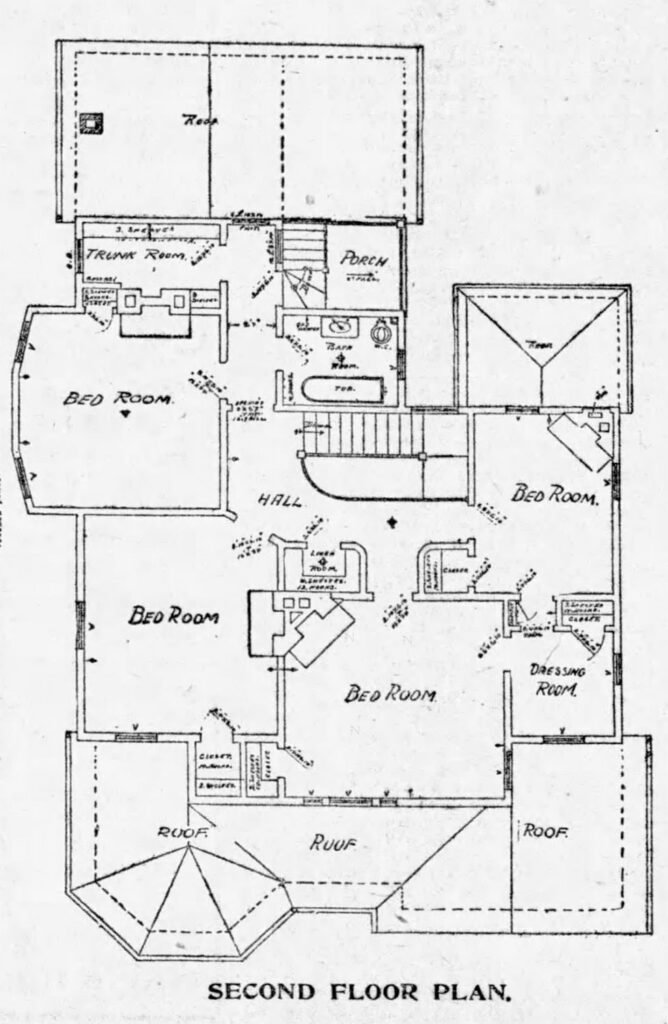

There isn’t much to criticize about the plan: Smith crafted a solid layout with 4 rooms on each floor clustered around a central stair hall. Each of the bedrooms included a closet, and the second floor contained a standard “trunk room” and dressing room, as seen in previous plans in this series.

Two oddities were the tiny den tacked on the back of the reception hall, and the massive dining room with an interior wall that awkwardly jutted out into the stairs hall.

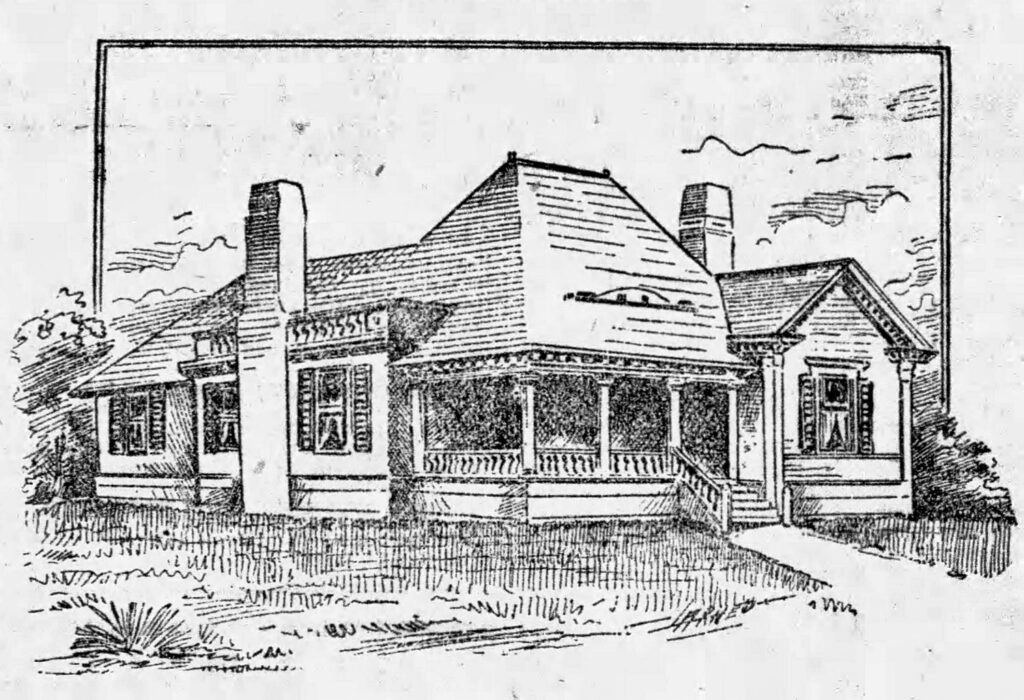

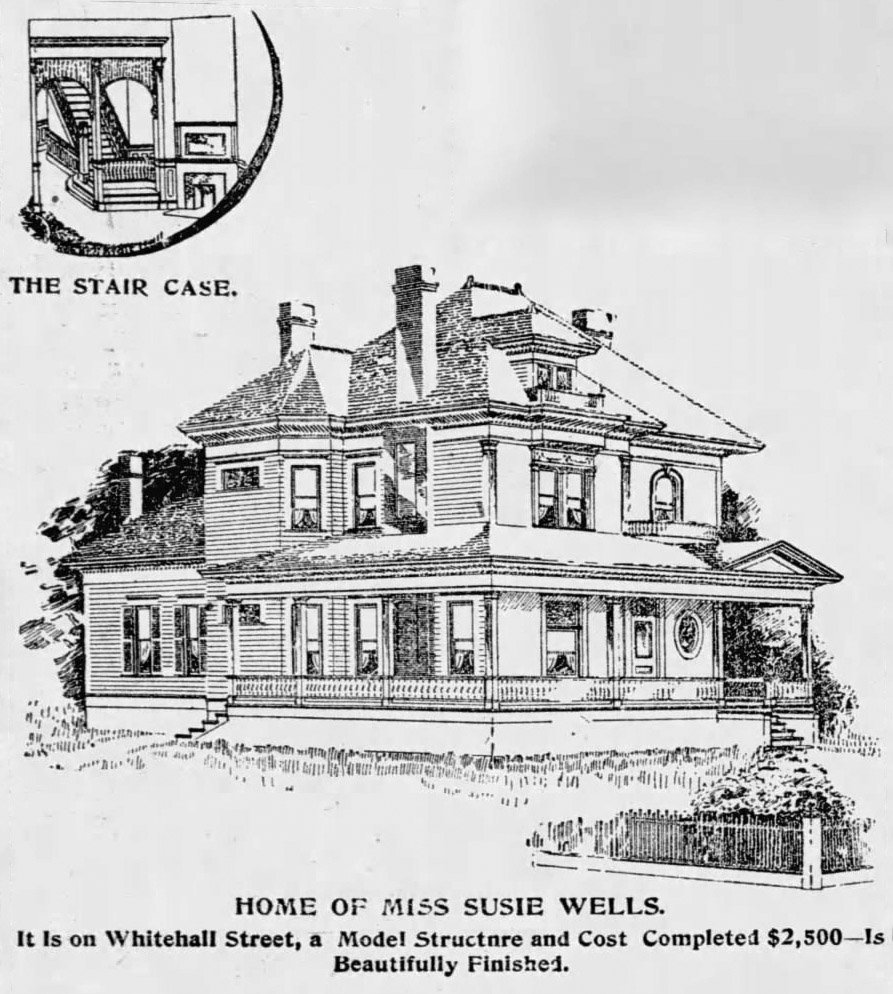

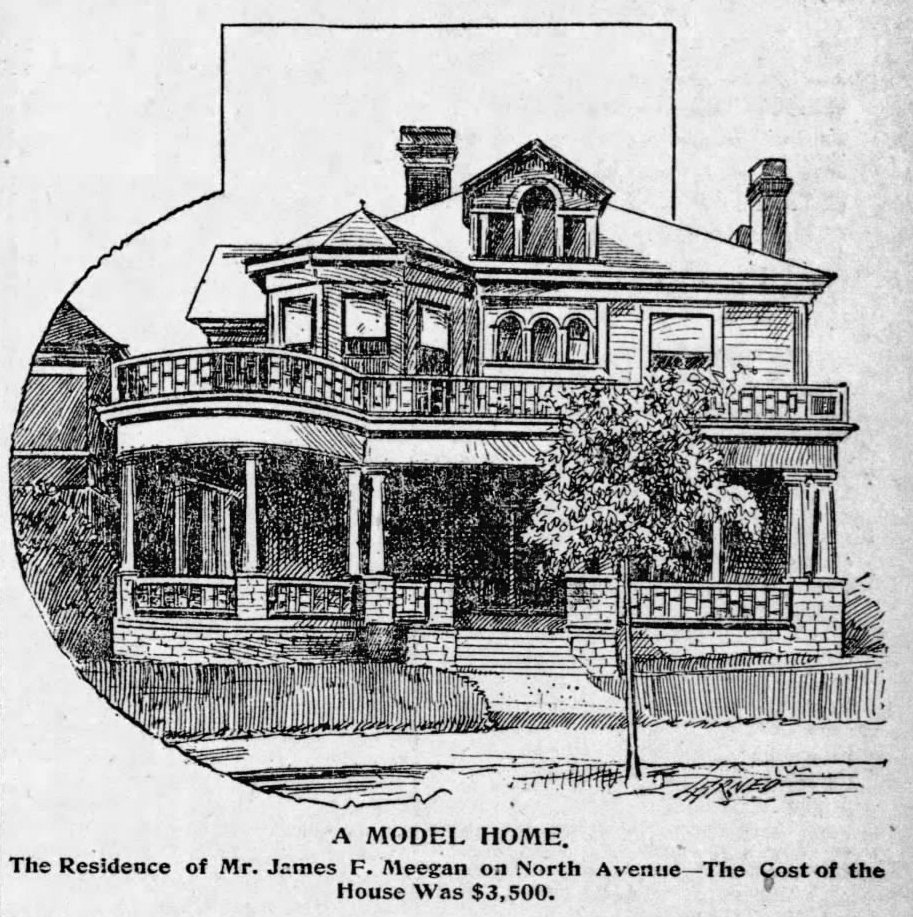

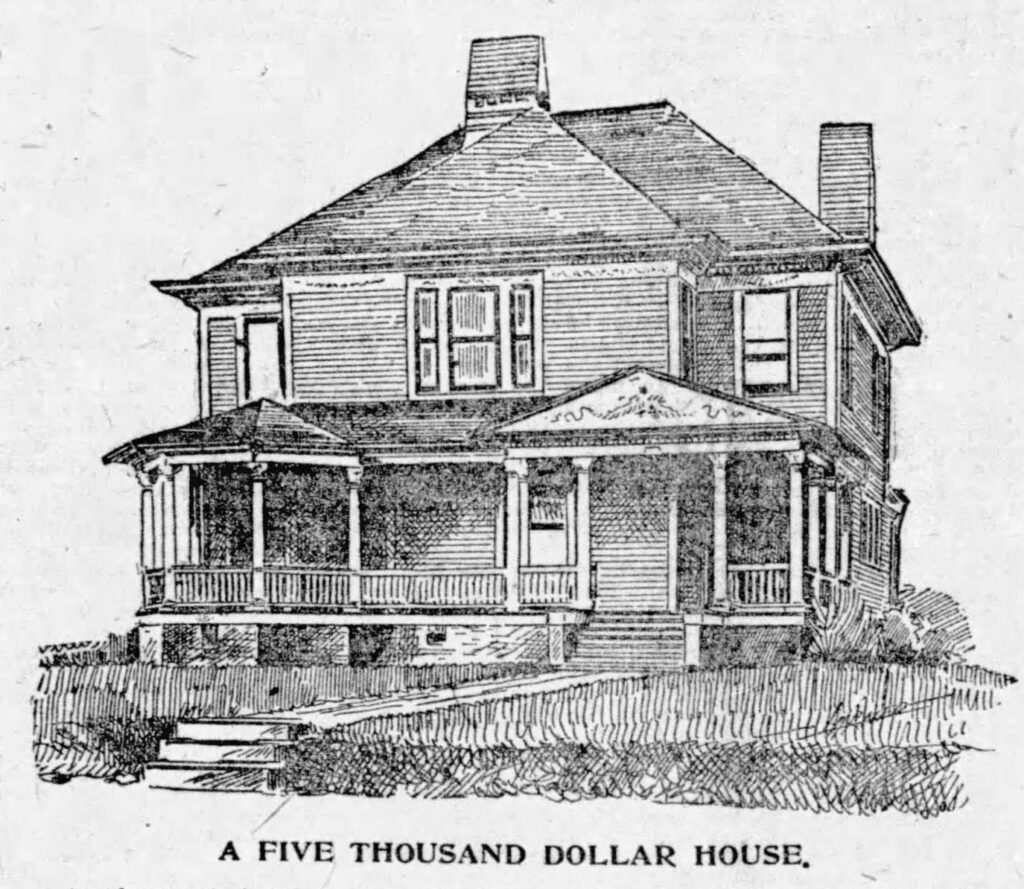

As noted in the article, the Wade House was designed in the nebulous “colonial” style of the 1890s, which, in this case, consisted primarily of dentilled cornices and decorative garlands on the friezes and porch pediment.

Festive garland ornamentation was Smith’s trademark element — you can find it in nearly all of his surviving buildings, as well as many of G.L. Norrman’s works from Smith’s time in his employment.

Also note the tapered chimneys, which were incorporated in numerous Norrman projects from the late 1880s to mid-1890s, again indicating the level of Smith’s involvement in Norrman’s firm.

Still, Norrman must have guided those designs with a fairly heavy hand, because Smith’s solo work lacked the panache of his mentor, and you can clearly see the limits of his ability in the Wade House illustration (pictured above).

Whereas Norrman consistently produced refined and cohesive compositions, Smith’s buildings often appeared boxy and plain with clumsy touches of embellishment — the Wade design is a prime example.

Located at 341 Gordon Street (later 249, then 1097 Gordon Street SW) in Atlanta’s West End, the home was occupied by the Wade family for only 3 years. Wade moved to Cedartown, Georgia, circa 1899,4 where he established a knitting mill that manufactured ladies’ underwear.5

Smith subsequently designed Wade’s home in Cedartown6 7 — which still stands, along with an additional knitting mill,8 which does not.

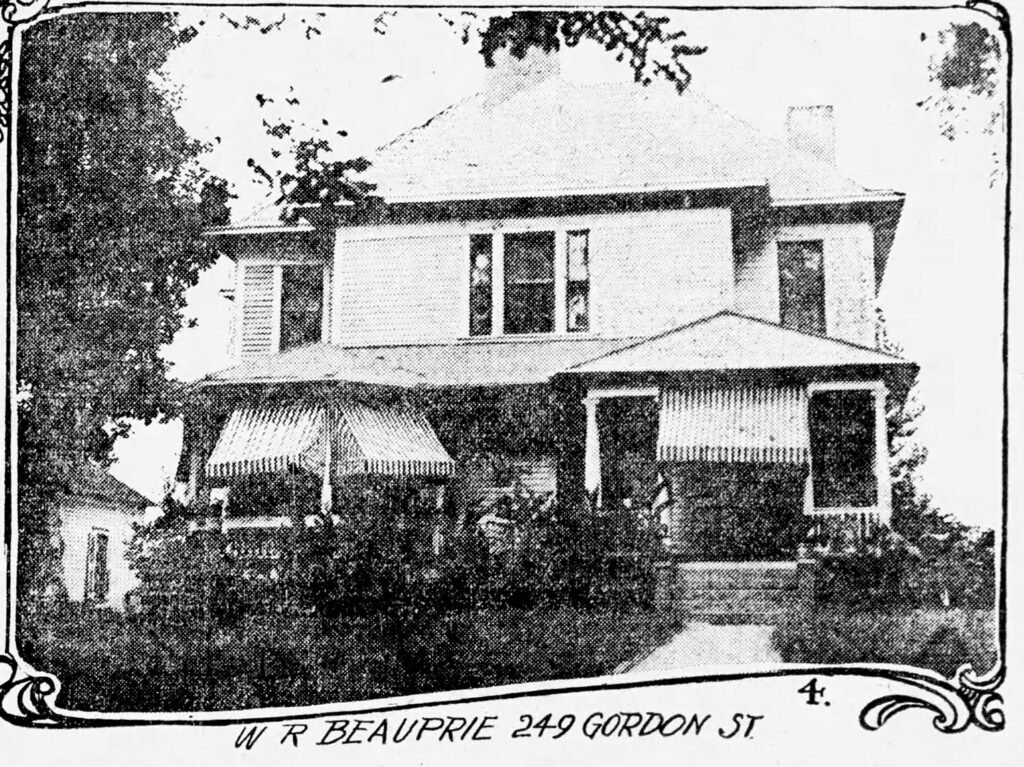

The former Wade home was occupied for many years by Mr. and Mrs. W.R. Beauprie. Mr. Beauprie died in the home in January 1922,10 while his wife, Carrie E. Beauprie, died in the home over 10 years later, in June 1932.11

The exact date of the home’s demolition is unclear, but in 1957, a newspaper classified ad said of the property: “Owner Leaving State SACRIFICE FOR QUICK SALE”, noting its commercial zoning and a location “Right in the path of progress.”12 By 1960, the site was occupied by — what else? — a gas station.13

Journal Model Houses; Residence of Mr. George Wade

The above cut shows a perspective view of Mr. George Wade’s house on Gordon street, at the corner of Lawton, in West End. It was built 18 months ago from the plans of Mr. Walter Smith of Atlanta, and is one of the prettiest and most comfortable homes in the city. Every inch of space is utilized, and the house is rich in closets and all kinds of conveniences.

The design of the modern colonial type and the picture shows how it is worked out. The construction is very thorough. The walls are double and the floors are double, with tarred felt between. The interior finish downstairs is antique oak with the exception of the parlor, the sitting room and the den. The parlor is in white enamel, the den in red oak, and the sitting room in curly pine.

There is a very attractive arrangement of the entrance, reception hall, stair hall and parlor. The reception hall, parlor and sitting room can be thrown together or completely separated by the sliding doors.

The second floor is natural pine, cabinet finish. The floors are waxed and polished. The windows are fitted with inside blinds and the house is equipped with electric bells, gas lighting and door openers. There are cabinet mantels in every room and in the hall and the stair hall is separated from the reception hall by pretty grill work, and the stairs are finished in antique oak. The foundation is a solid wall, and there is a good brick basement with a furnace room.

The plumbing is the best and thoroughly ventilated. The workmanship throughout is first class and the house is a gem. It cost when built $5,240, and can be duplicated for about $5,000. The painting is in the prevailing colonial colors.14

References

- “A Card”. The Atlanta Constitution, March 1, 1893, p. 10. ↩︎

- Atlanta City Directory Co.’s Greater Atlanta (Georgia) city directory (1894) ↩︎

- “Out For Himself.” The Atlanta Constitution, April 19, 1896, p. 20. ↩︎

- “Loitering In The Lobbies”. The Atlanta Journal, February 6, 1899, p. 10. ↩︎

- “The Wahneta Mills.” The Macon Telegraph, January 2, 1899, p. 8. ↩︎

- The Cedartown Standard (Cedartown, Georgia), August 30, 1900, p. 2. ↩︎

- “Improvements At Cedartown”. The Atlanta Constitution, September 15, 1900, p. 4. ↩︎

- The Cedartown Standard (Cedartown, Georgia), August 16, 1900, p. 3. ↩︎

- “Scenes and Streets of Homes in West End”. The Atlanta Journal, August 23, 1914, p. 8H. ↩︎

- “Mr. W.R. Beauprie, Well Known in Atlanta, To Be Buried Sunday”. The Atlanta Constitution, January 14, 1922, p. 10. ↩︎

- “Fall Injuries Fatal To Mrs. C.E. Beauprie”. The Atlanta Constitution, June 5, 1932, p. 10A. ↩︎

- “Business Property 165”. The Atlanta Constitution, June 21, 1957, p. 27. ↩︎

- “100 Extra Gold Bond Stamps!” (advertisement). The Atlanta Constitution, June 16, 1960, p. 29. ↩︎

- “Journal Model Houses; Residence of Mr. George Wade”. The Atlanta Journal, February 12, 1898, p. 10. ↩︎