The Background

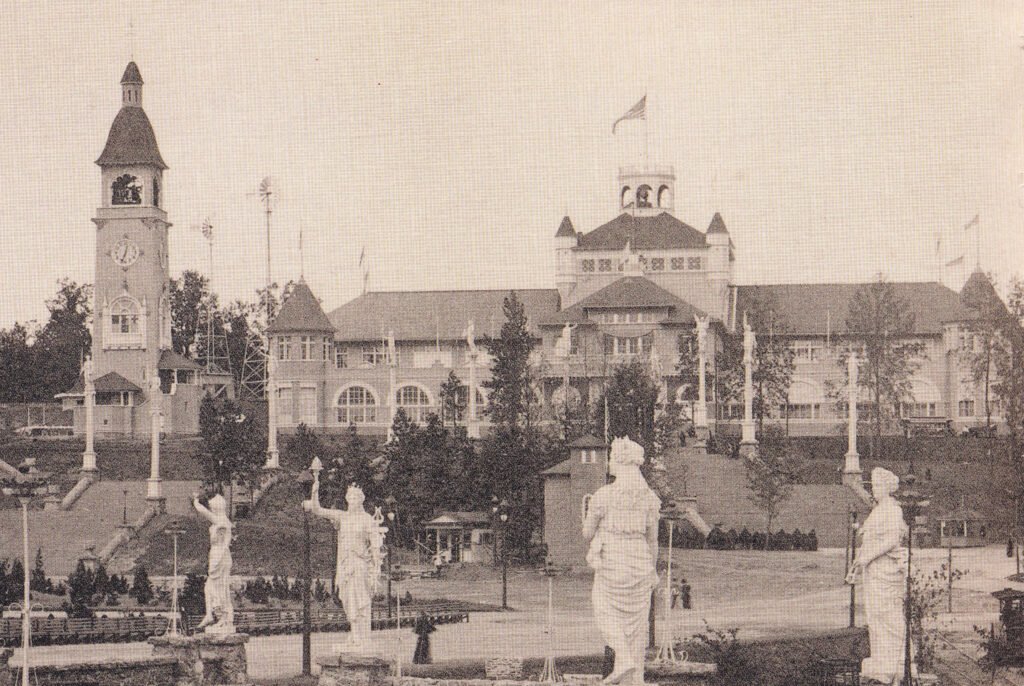

Atlanta and the United States were in the throes of the Great Blizzard of 1899 when Wallace Putnam Reed, a friend of G.L. Norrman‘s, wrote the following article as part of his weekly column in The Atlanta Constitution.

Two days before the article’s publication, Atlanta received 6.5 inches of snow and recorded its all-time low temperature of nearly -9 °F1 2 in a cataclysmic nationwide cold snap.

Described by one forecaster as “probably the most remarkable in the history of the country”,3 the blizzard left hundreds of Atlantans stranded without food and fuel for heat,4 5 6 and caused more than $1 million of crop losses in Georgia and $100,000 of pipe damage in Atlanta.7 8

With the ice and snow still melting, Reed asked a timely question: “Is our climate changing?”, and introduced his readers to Norrman’s belief that Earth’s geographic poles cataclysmically shifted at earlier points in its history, a debunked pseudo-scientific theory that was first hypothesized in the late 19th century.

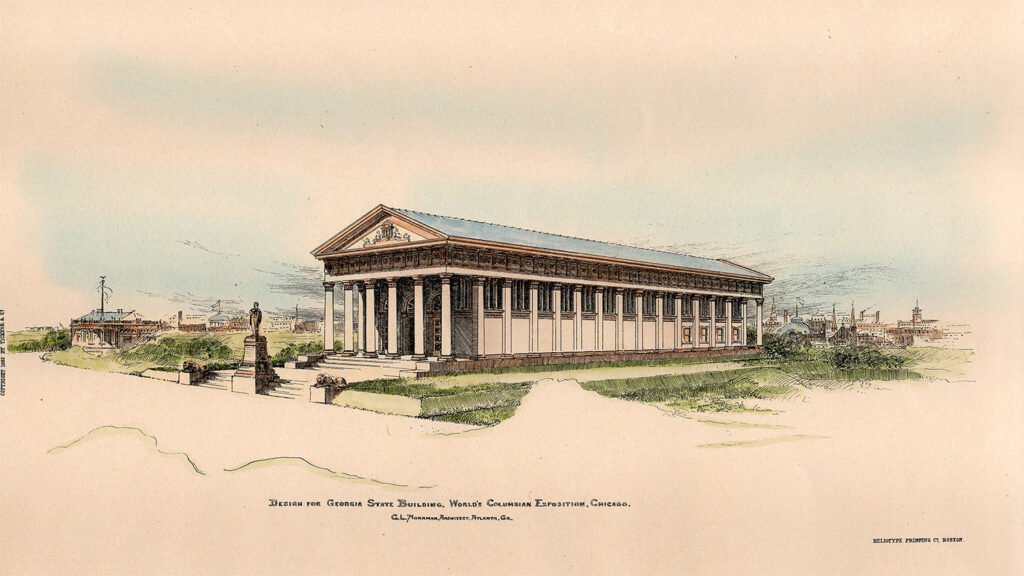

The article served as a promotion for Norrman’s pamphlet, Architecture as Illustrative of Religious Belief, in which he explained his pole-shift hypothesis, among other theories.

Here, Reed referred to the infamous “Cold Friday” of 1833, which was previously reputed as the coldest day on record in the Atlanta area,9 although the city didn’t even exist at that point. Reed also mentioned Terminus and Marthasville — both were early names for Atlanta.10

Our Polar Weather And Its Suggestions

Is our climate changing?

Occasionally this question is asked in a humorous way by some old-timer who takes the position that the war ruined everything down this way, including our weather.

But the suggestion has a serious aspect.

A few exceptionally cold winters in the course of a century, or a dozen centuries, would not be conclusive proof of a permanent change of climate.

This globe of ours is very old. According to the scientists, it is at least 100,000 years old, and in that period many remarkable physical revolutions have occurred.

Of course we have had very cold spells in Georgia before the present age. Everyone of my older readers is ready right now to remind me of that memorable and destructive freeze two generations ago, along the thirties, shortly before the big panic.

That was bad enough, but there were fewer people here to suffer in those days, and Atlanta escaped entirely, because there was then no Atlanta—not even Marthasville or Terminus; and I doubt whether Hardy Ivey [sic] had built his solitary cabin on the site of our metropolis.

It was a terrible visitation—that cold Friday. Fruit trees, vegetation and crops were ruined. Thousands of forest trees exploded–bursting wide open.

The people had not recovered when the panic came. then, cotton fell 3 or 4 cents, and many farmers lost everything. Their creditors pushed them to the wall, and sold them out, not sparing even their beds, pots and kettles and cheap tableware.

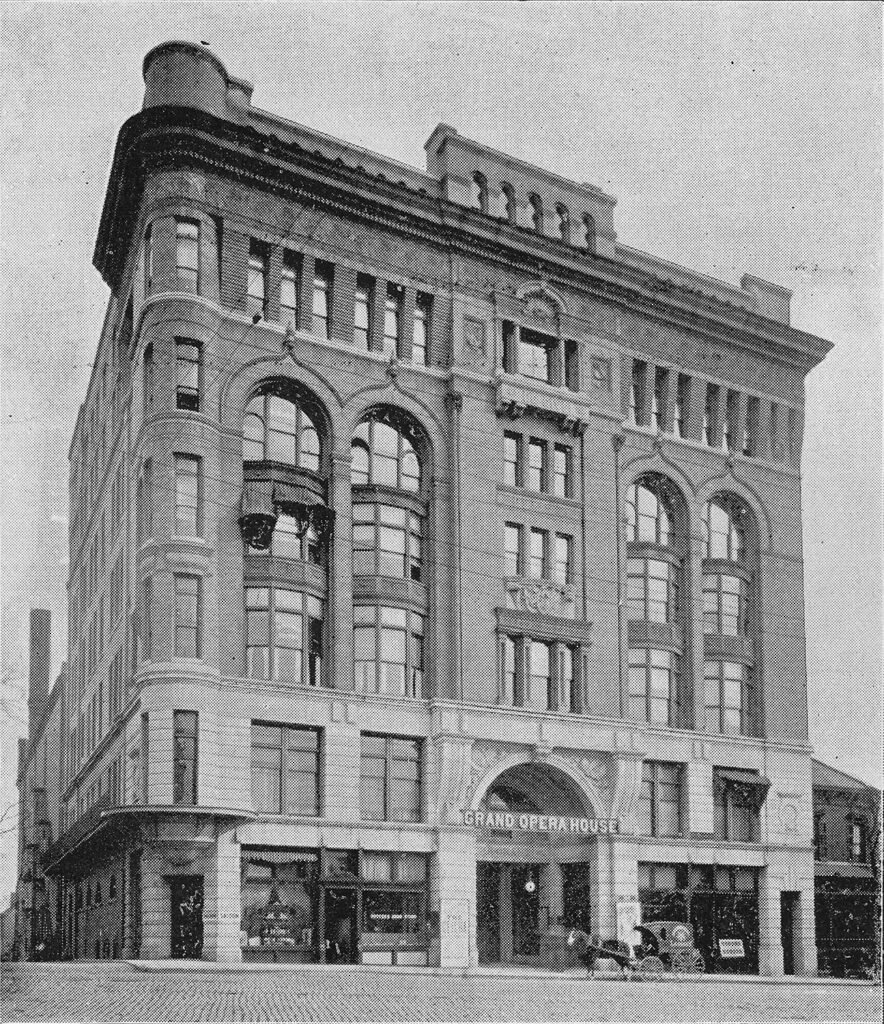

Some scientific men maintain that in the remote past this was a very cold region. Mr. G.L. Norrman touches upon the subject very entertainingly in his recent pamphlet, entitled “Architecture as Illustrative of Religious Belief.”

Mr. Norrman accounts for the flood by suggesting that sometime during the earth’s existence the accumulation and congealing of the vapors at the poles made them the largest diameter of the globe, and, when this took place, the earth naturally found its equilibrium on a different axis, and turned about 90 degrees.

This is a very startling suggestion, and there is a sufficient basis of fact for it to attract the attention of the thoughtful.

The pamphlet referred to in the foregoing paragraphs says that the poles were perhaps changed from some points near the present equator, taking the place of the former equator at points near the present poles. If such a change in the poles occurred, it would account for many curious phenomena on this sphere.

Such a change would of course change the beds of the oceans.

What are now productive valleys may have been the bottom of the ocean, and the present bed of the ocean may have been tilled valleys, ages and ages ago.

This change of the oceans would have caused a tremendous rush of the waters, destroying everything in their way.

It would account for the phosphate beds, where animals of every kind—lions, tigers, elephants, fish and reptiles—are piled together, as firmly as if a million Niagaras had rammed them in the crevices where they are found.

The coal beds, also, may have had a similar origin, though they may be traced to other causes.

Only some such catastrophe as the changing of poles will satisfactorily account for the remains of tropical plants and animals under the ice and snow in Siberia and Greenland, and the existence of glaciers at the equator.

Remains of tropical animals and plants could hardly have been in the arctic regions, unless that part of the earth had been tropical at some time, and unless a very sudden change in the temperature had taken place.

Whatever power caused the phosphate beds, the coal beds and the existence of tropical plants and animals under the ice and snow of the arctics was necessarily a power sufficiently great to destroy nearly every vestige of life and civilization.

Only on isolated mountain tops could life have been preserved.

People do not like to think of such gigantic convulsions of nature, and contemplate the possibility of their repetition.

Yet, the pendulum always swings backward. Its return may be delayed, but sooner or later it must come.

It is possible, therefore, that sometime in the future another violent shock will cause the present poles and the equator to change places; or again reoccupy their former localities.

The human mind can hardly grasp the full meaning of such a change.

Under such conditions the now frozen regions around the poles would be transformed into productive garden spots, while our south Atlantic and gulf states would be buried under mountains of perpetual snow and ice.

Intrepid explorers would probably make their way to Georgia, Florida and Cuba, and return to their tropical Greenland homes with big stories of the polar bears and reindeers seen in this locality.

Fortunately, there is no immediate danger, unless a tremendous earthquake should unexpectedly bring about the change.

For hundreds, and possibly thousands of years to come, this will probably remain the sunny south, with a delightful climate, and a rapidly increasing productive capacity.

The speculations of the scientists will not justify anybody in knocking off work and neglecting the improvement of their real estate.

If Georgia ever becomes an arctic territory again, it will probably be thousands of years hence. By that time our history will have been forgotten. New races may then live here. Perhaps not a vestige of our present civilization will remain.

So we need not concern ourselves bout these matters.

Some years ago there was a very brilliant Atlantian of a scientific turn of mind who was greatly worried over the idea that an earthquake or a canal across the isthmus of Panama might divert the gulf stream from its course, and turn this region into a frozen waste, where no human beings could exist, but his warnings did not alarm many people.

Let us leave the calamities of the future to those who will have to bear them. In the meantime we have our hands full taking care of ourselves and the sufferers at our doors during our occasional blizzards.

Wallace P. Reed11

References

- “Coldest Ever Known in Atlanta; Eight Degrees Below at 7 O’Clock”. The Atlanta Journal, February 13, 1899, p. 1. ↩︎

- ‘Coldest Day on Record Yesterday; Celebrated “Cold Friday” Outdone’. The Atlanta Constitution, February 14, 1899, p. 1. ↩︎

- “Back of Blizzard Is Broken; Work for the Needy Yesterday”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 15, 1899, p. 1. ↩︎

- ibid. ↩︎

- “Coldest Ever Known in Atlanta; Eight Degrees Below at 7 O’Clock”. The Atlanta Journal, February 13, 1899, p. 1. ↩︎

- “How Atlanta Furnished Food and Fuel to Sufferers from the Cold”. ↩︎

- “How Blizzard Struck Georgia; Peach Crop Will Be a Failure”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 14, 1899, p 1. ↩︎

- “Effect and Cost of Blizzard to Atlanta and Georgia”. The Atlanta Journal, February 15, 1899, p. 5. ↩︎

- ‘Coldest Day on Record Yesterday; Celebrated “Cold Friday” Outdone’. The Atlanta Constitution, February 14, 1899, p. 1. ↩︎

- History of Atlanta – Wikipedia ↩︎

- Reed, Wallace P. “Our Polar Weather and Its Suggestions”. The Atlanta Constitution, February 15, 1899, p. 4. ↩︎