On early summer mornings at the local botanical garden, you can find all sorts of fine flowers and flying friends. Here’s a lovely pair I spotted last Saturday.

On early summer mornings at the local botanical garden, you can find all sorts of fine flowers and flying friends. Here’s a lovely pair I spotted last Saturday.

In June 1899, The Atlanta Constitution launched “The Constitution‘s Home Study Circle”, consisting of long-form printed lectures on a variety of subjects, with the promise of “instruction and general culture for those who make the most of its benefits”.

Upon announcement of the program, G.L. Norrman wrote the Constitution to express his tentative approval, as seen in this letter “From Mr. G.L. Norrman.”, published on June 8, 1899.

‘The “Home Study Circle” is on the right line. I am not familiar with the details of your plan, but a glance at your course of free lessons for your readers convinces me that they will be of great value to those who will give them proper attention. Education and culture cannot be purchased in job lots, nor picked up in the road, but some systems and methods are easier and more attractive than others, and I think that your scheme of popular instruction is a good one, and will be appreciate by hosts of old and new readers.’

Very sincerely,

G.L. NORRMAN2

This fine specimen of Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) is a little south of its native range, but the species is a popular choice in urban landscapes throughout the United States because of its fast growth, endurance in tough conditions, and year-round greenery. Hey, it’s better than another crape myrtle.

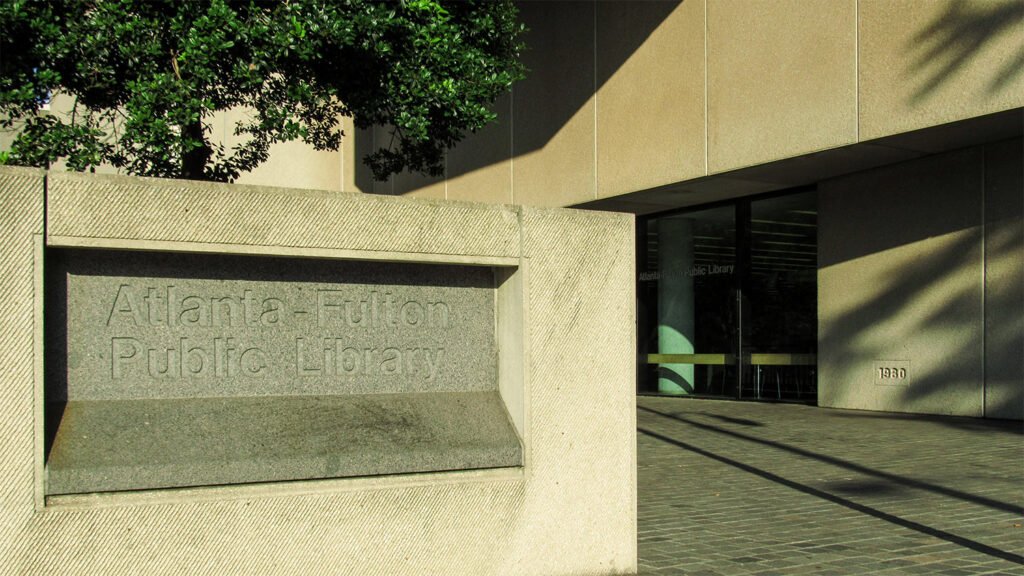

I was introduced to the work of Marcel Breuer with the Atlanta Central Library (1980), which was designed as a conscious rehash of Breuer’s Whitney Museum in New York and is perhaps the most emblematic example of Atlanta’s consistent impulse to copy the architecture of better cities (badly).

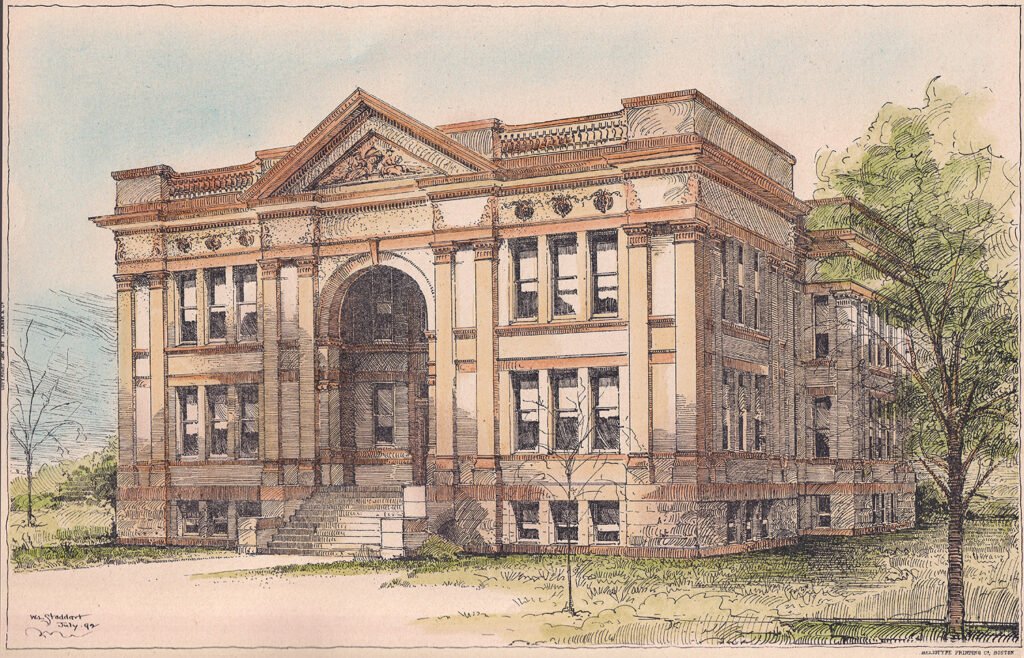

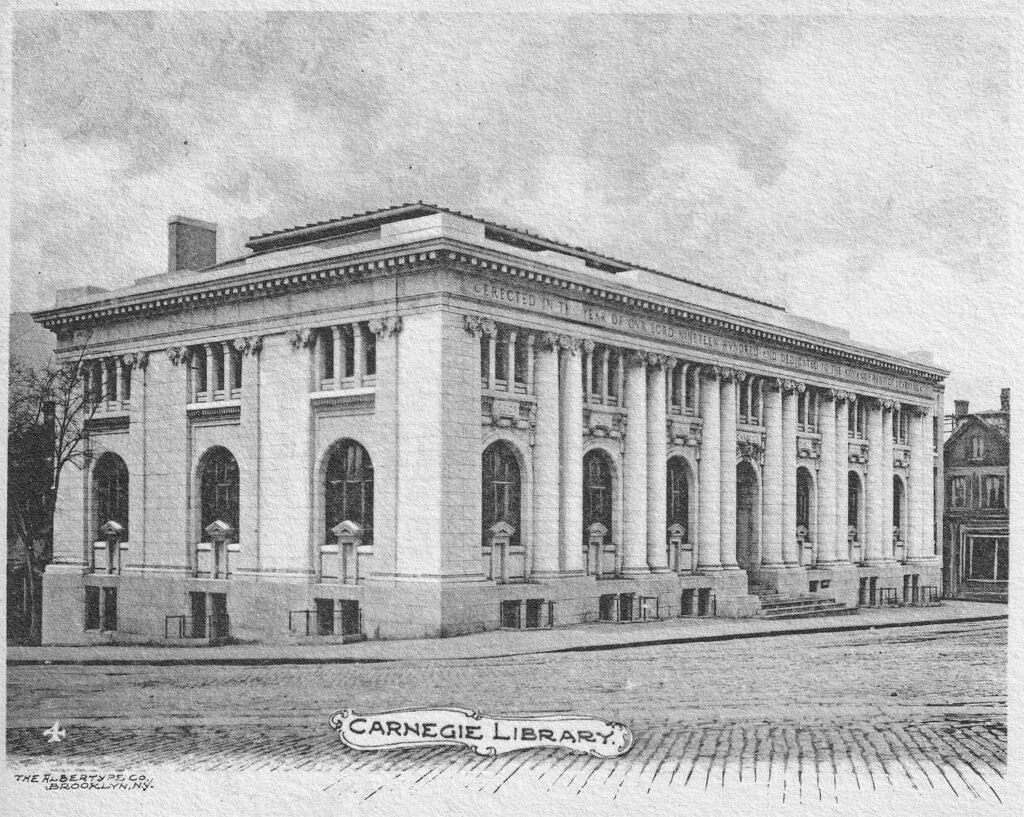

Breuer’s firm was hired to design the building in 1970,1 but in typical Atlanta fashion, no one wanted to pay for the new facility, even though the city’s 1902 Carnegie Library (pictured below) was in disrepair, overcrowded, and “hopelessly outmoded”.2

In lieu of actual decision-making, local leaders spent years quibbling over where the library should be built,3 4 5 6 7 8 while simultaneously denying funds for its construction. In his 1973 mayoral election campaign, Maynard Jackson even promised that only private donations, not tax dollars, would be used for the project,9 10 which had an original estimated cost of $13 million but with runaway inflation had jumped to nearly $20 million by 1974.11

Meanwhile, the old library remained in abysmal condition, and an unusually pointed news commentary from that year said of it: “The dingy granite building on Carnegie Way, with its creaking floors and bulging stacks, stands as a pathetic reminder of the place of culture in this modern commercial capital.”12

The library’s director, Carlton Rochell, was equally dismissive of the aging Beaux-Arts building, stating that “…even at its best, it was just one of about 4,500 things cut out with Carnegie’s cook-cutter.”13 He wasn’t wrong.

Rochell was the driving force behind the new library’s development, and his explanation for why he chose Breuer as the designer was the embodiment of Atlanta smugness:

“We narrowed it down to three or four architects with enviable reputations. We settled on Marcel Breuer because we regard him as being at the pinnacle of his profession. Besides, I felt that Atlanta should have the distinction of a Breuer-designed building. There’s one other thing. Marcel Breuer is notable for living with a budget.”17

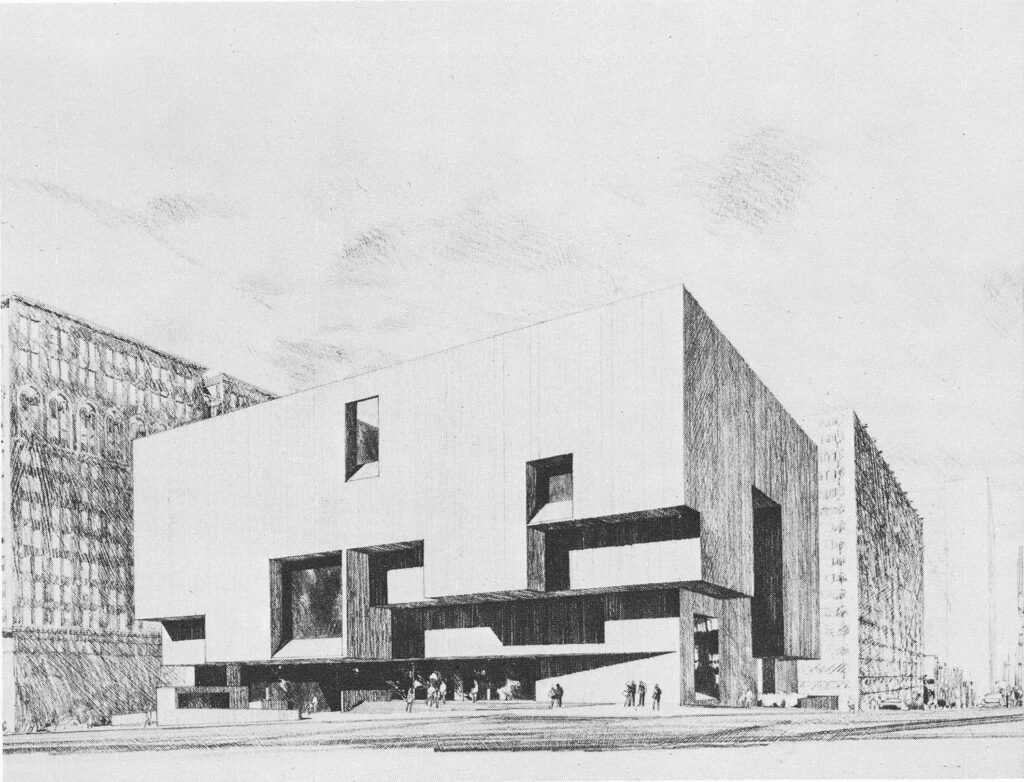

The final 2 contenders were Breuer and Paul Rudolph, but it appears Rochell intended to hire Breuer all along, as he was said to be “highly enamored of the Whitney Museum”.18 When Breuer’s conceptual design19 for the new library was approved in March 1971,20 The Atlanta Journal claimed it “borrows somewhat from the Whitney Museum of Art…”,21 which was quite the understatement.

By the early 1970s, it appears Breuer all but gave up actual design work, primarily handing those duties over to his associates while he secured commissions and cashed in on his reputation.

With his firm increasingly cranking out retreads of past glories, Breuer showed no qualms about the derivative design of the Central Library, and of its severe Brutalist style, he said it conveyed “an expression which you may call monumental”.23

That made more sense than the firm’s official design statement for the project. If you can decipher this first-class wankery, mazel tov:

“Admist this heterogeneous downtown texture, the library building must, somehow, be given an architectural significant appropriate to one of the chief cultural resources of a major city. The achievement of this distinctness and clarity is considered a key design challenge by the architects.

The design response aimed at this goal is based on concepts which seek to take maximum advantage of the important circumstances that the library site is a complete block; and that the building that occupies it may thus be separated by an envelope of space from adjacent structures.”24

Despite constant lobbying by Rochell, heavy support from the city’s newspapers, and a special commission’s recommendation to issue a bond for funding the library’s construction,25 the city council and Maynard Jackson — who was elected mayor in 1974 — continued to dither on the matter.

In April 1975, the Friends of the Library released a damning statement that cut through the heart of Atlanta’s ludicrous self-aggrandizement: “It is unthinkable that such a valuable asset as the public library sits like a forgotten dowager on the corner of Carnegie Way while Atlanta touts itself as the world’s next great city.”26

Bowing to mounting pressure, the city council finally scheduled a bond referendum for December 1975,27 although its prospects for passage appeared bleak: a citywide survey released in October 1975 revealed that 56% of Atlantans disapproved of a bond issue to finance a new library.28 That same survey, however, found that 60% of citizens “thought Atlanta’s image is ‘very important’”,29 proving that Atlantans are as ignorant as they are narcissistic.

Atlantans are also too apathetic to vote, so it was a shock when 28.6% of voters — much higher than anticipated — showed up to the polls and passed the $20 million bond for the library’s construction.

The vote was largely along racial lines: Black voters overwhelmingly voted for the library, while white voters soundly rejected it.30 That part isn’t surprising — most Southern whites wouldn’t be caught dead in a public library.

The library’s initial plans only consisted of a model and simple schematic drawings,31 and the final plans weren’t completed until early 1977.32 33 In 1976, Breuer retired from design work completely due to poor health,34 35 so credit for the Central Library’s design should go almost entirely to Breuer’s associate architect, Hamilton Smith.

The budget for the library’s construction was set at $18.9 million during the bond referendum, and to stay within those constraints while material and labor costs increased, Smith reduced the building’s footprint to 185,000 square feet. The library’s board of trustees pushed back on that, however, demanding the project remain at the larger size,36 which apparently resulted in steep cuts to the interior design.

Groundbreaking for the library took place in September 1977,37 38 but the project faced numerous setbacks before it began, in addition to issues during the construction process. Among the low points:

Built on the corner of Forsyth Street and Carnegie Way in Downtown Atlanta, the completed Central Library encompassed 250,000 square feet58 across 10 levels, with 8 floors above ground level, repeating the triple cantilevered design of the Whitney Museum.

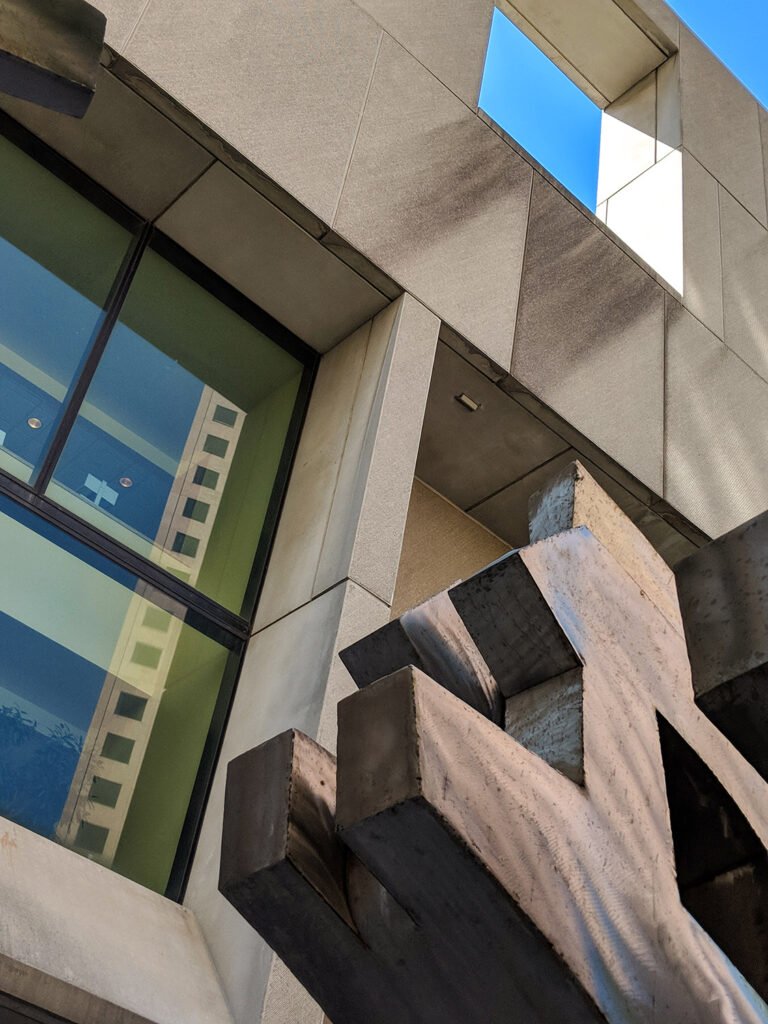

To accommodate Atlanta’s meager funding, the library’s exterior was covered in vertical board-formed concrete,59 a much cheaper material than the granite tiles used on the Whitney.

A defining feature of the building is the 25×25 ft. square window60 on the front facade that spans 2 floors, while a trademark trapezoidal window is tucked into the north side at street level.

Opening in May 1980, the library included such novel features as a gift shop, cafe, sunken garden (tres 70s), a rooftop terrace, drive-through window, and a 340-seat auditorium.61 62 The original plan called for 6 above-ground floors, but Smith was able to add 2 unfinished “bonus” floors and still stay within budget.63

That was probably because so little was spent on the interior, which only has a few of Breuer’s flourishes in the stairwells and the first basement level, notably bush-hammered concrete, bluestone tiles, and coffered ceilings.

The remainder of the building’s interior spaces were finished out like a drab 1970s office building, with dropped fiberglass ceilings, fluorescent strip lighting, industrial-grade carpeting, and standard furnishings.

The Atlanta hype machine would have you believe the Central Library is one of Breuer’s best works, but that’s complete bullshit. It is, at best, a mildly interesting mash-up of elements from some of Breuer’s earlier projects, none of it executed that well.

Partially buried in a slope, the library appears dreary, faceless, and foreboding, and the floating effect seen in the Whitney design is conspicuously absent. The 2 bonus floors added to the top give the composition too much visual heaviness, and the building is more reminiscent of a sinking tombstone than a grand public monument.

Because Atlanta’s infantile leaders putzed around for a solid decade, by the time the library was completed, the Brutalist style was already rapidly falling out of fashion, an embarrassment for a city that so self-consciously tries to sell itself as a modern metropolis on the leading edge (it’s not).

The building initially enjoyed ample sunlight in its windows and skylights, but that quickly changed with the construction of the nearby Georgia-Pacific Center, which has cast a permanent shadow over the library since 1982.

In 1970, Carlton Rochell stated that the planned facility would be adequate for 20 years,64 and when the Central Library was still under construction, Ella Yates confirmed: “Our new edifice…moves us into the year 2000”.65

But 20 years in Atlanta might as well be a hundred, and in 2001, the library was described as “worn” and having suffered from “twenty years of decay and obsolescence”. The director at the time observed that it was “built for a different Atlanta, a different world. It was all pre-computer.”66

Circulation at the library had dropped steeply, and since Atlanta never properly maintains its buildings, the facility had predictably fallen into disrepair. The most significant issue was that a leaking planter at ground level led to the collapse of a portion of the auditorium’s ceiling beneath it, resulting in the auditorium’s closure for 5 years.67

A paltry $3 million renovation began in 2001 and extended into 2002, consisting of little more than essential repairs, new paint and carpeting, and additional computers.68 69

In 2008, the Fulton County Commission held a referendum for a $275 million bond issue, with the stated intention to fund a new 300,000-square-foot library as a replacement for the aging Breuer building. Like every Atlanta development since the 1996 Olympics, the proposed library was obligatorily described as “world-class”,70 although you can be sure it wouldn’t have been.

The bond passed, but — no surprise — Atlanta’s leaders waffled about the library’s fate for nearly a decade. With the threat of destruction pending, local, national, and even international protests by architects and preservationists mounted, and in 2010, the Central Library was placed on the World Monuments Watch list.

Finally, in July 2016, the county commissioners opted for a full renovation of the building instead of demolition, although their decision was motivated by money more than any desire for preservation: the new library proposed 8 years earlier was expected to be partially funded by private donations, but those failed to materialize during the Great Recession.71

The library closed for renovation in July 2018 and reopened in October 2021. Therenovation was designed by Cooper Carry of Atlanta, likely chosen, in part, because of that firm’s recent work on the new campus for North Atlanta High School (2013),72 which required the conversion of a hulking suburban office building completed in 1977.73

There was a key difference between the 2 projects, however: the high school was housed in an unremarkable corporate structure designed by a hometown firm,74 while the library was a landmark civic building credited to an international architect. That the city’s leaders decided local designers were qualified to rework the building tells you everything you need to know about Atlanta.

Preservationists were most concerned about Cooper Carry’s decision to add strips of windows to the front of the Central Library for increased sunlight, although that turned out to be one of the better decisions — I would argue that it was an improvement.

On the exterior, the entrance plaza was completely reworked: the sunken garden was filled in, and a large metal sculpture added in 1983 (Wisdom Bridge by Richard Hunt)76 was scrapped. Neither removal was a huge loss.

The renovation went very wrong in the reworked interior, where no attempt was made to blend the new design with the original Breuer elements. The project’s designers were clearly more interested in leaving their own mark than enhancing the building’s existing character, and the result is as awkward as it is arrogant.

The worst decision was that the building’s original service elevators were ripped out and replaced with a swirling skylit atrium that looks extracted from a Class B office building circa 2010, ineptly styled with glass railings, a tacky hanging sculpture, and a dull gray and brown color scheme that already looked dated upon completion.

The renovated interior has a confusing and schizophrenic design that clumsily shoehorns a sleek and sterile 21st-century atrium next to a 70s-era stairwell of stone and concrete. The new atrium also removed a huge chunk of usable floor space from each floor, making the interior feel small and cramped — more evocative of a branch location than a flagship library.

Atlanta architecture is third-rate as a rule, but even by the city’s low standards, the Central Library’s renovation is particularly awful, turning an already flawed work into an incoherent mess that appears both amateurish and cheap, despite a reported $50 million price tag.

The building’s fundamental problems remain, and the library is as grim and lifeless as ever, having all the charm of a minimum-security prison — complete with hostile security guards manning the front door.

At Breuer’s death, Carlton Rochelle claimed “…history will show, that Breuer was one of the three greatest architects of this era”, naming the other two as Eero Saarinen and Mies van der Rohe.77

That was a flawed assessment that hasn’t aged well. While Mies is still considered one of the most influential architects of the 20th century, Saarinen is all but forgotten now, with his gimmicky designs viewed as little more than Space Age novelties.

Breuer is arguably even less known than Saarinen, and when Atlanta inevitably demolishes the Central Library for some hideous new structure in the future, not even the most die-hard Breuer admirers — if there are any left — will consider it much of a loss.

The June 13, 1899, edition of The Atlanta Journal published remarks from G.L. Norrman about Huntsville, Alabama, where he had just returned “from a business visit”.

Norrman may have visited that area in connection with plans for the renovation of the Lauderdale Court House in nearby Florence, Alabama, which was awarded days later to Golucke & Stewart of Atlanta.1

It’s unclear if Norrman ever completed any work in Huntsville or North Alabama, although he designed multiple projects in Anniston and Gadsden, Alabama, in the late 1880s, and briefly considered moving his practice to Birmingham, Alabama in late 1899, when he was designing the Bienville Hotel (pictured above) in Mobile, Alabama.

The spring he refers to here is the Big Spring in downtown Huntsville.

“I like Huntsville very much. It’s a pretty, thrifty little town—the people there dress well and seem to be prosperous and the streets are full of elegantly dressed, handsome ladies.

“A great stream of water, twenty-odd feet broad, gushes from rock to the tune of over a million gallons a minute. It is a most refreshing sight— this spring. This hot weather a man can almost keep cool who carries around a picture of the Huntsville spring in his mind.”2

A masterpiece of the Brutalist style, the Whitney Museum of Art (1966) in New York was designed by Marcel Breuer (1902-1981), an American modernist architect of the 20th century.

Like so many architects of his era, Breuer’s legacy has been rapidly forgotten in the 21st century, with many of his buildings now under threat or destroyed.

Born in Hungary to a Jewish family, Breuer (pronounced Broy-er) was both a student and teacher at the Bauhaus in Germany, where he became known for his cutting-edge furniture designs, most famously the Wassily chair.

With the rise of the Nazi regime, Breuer moved to England in 1935, then immigrated to the United States in 1937 with his mentor, Walter Gropius, becoming a member of the influential Harvard Five group of architects.

Between 1938 and 1941, Gropius and Breuer designed several residential projects together before Breuer broke off and began his solo practice. One of their joint works is the Weizenblatt Duplex (1941) in Asheville, North Carolina, for which Breuer is credited as the primary designer.

Breuer’s architectural career is neatly bifurcated into 2 distinct periods that couldn’t be any less alike.

In the 1940s and 50s, he was chiefly a small-scale designer and specialized in the creation of light, airy International style residences that were much praised for their innovative floor plans and use of materials and building techniques.

In the 1960s and 70s, Breuer abruptly switched gears and almost exclusively produced larger and more lucrative corporate and civic projects in the forceful and imposing Brutalist style, using concrete as his primary material.

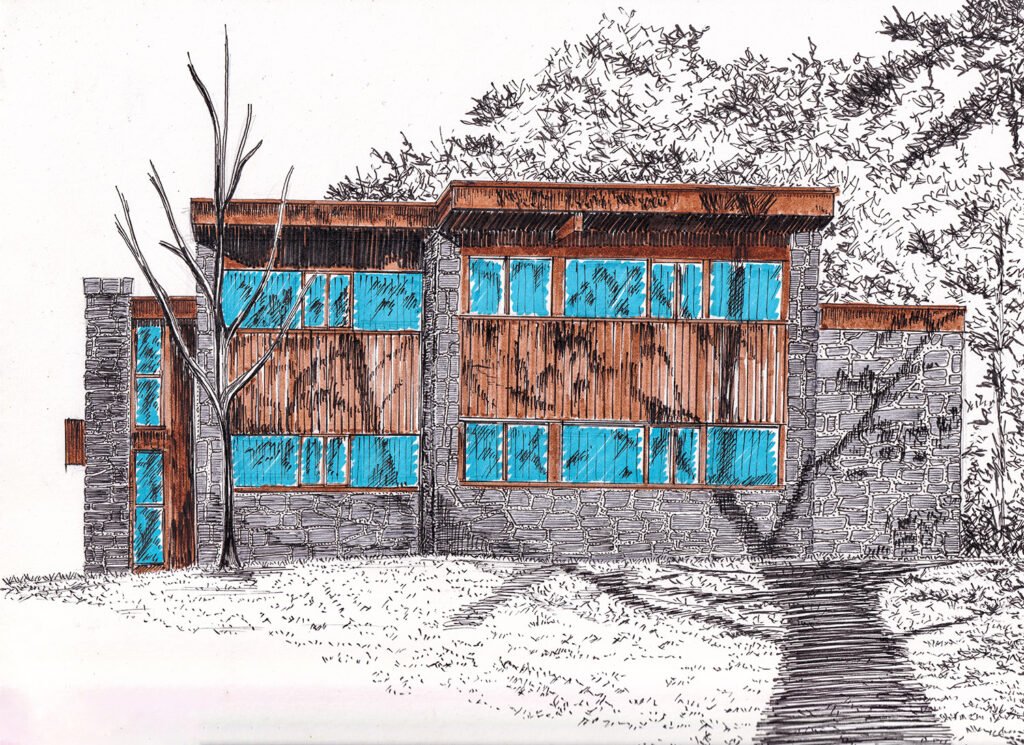

A typical design of Breuer’s residential period, the Snower House (1954) is also one of his least-known projects, occupying a large corner lot in the Mission Hills suburb of Kansas City.

The design is essentially a 1,800-square-foot rectangular box cantilevered on a concrete block base and was reportedly modeled after Breuer’s first home in New Canaan, Connecticut2, although most of his houses from the era had a similar look.

Breuer’s work was heavily concentrated in New England and the East Coast, and together with a house in Aspen, Colorado, the Snower house is one of only 2 completed residential projects he designed west of the Mississippi River3 — he never even visited the property.4

No one would claim the Snower house is one of Breuer’s better works, but it still has all the trademarks of his early residential designs. Notably, the home utilizes Breuer’s “bi-nuclear” floor plan, with living spaces placed on one side and sleeping areas on the other.

You can also clearly identify Breuer’s attention to form and creative use of materials: large windows on every side of the home blur the boundary between exterior and interior, tiny windows punctuate walls patterned in cedar strips, and brightly-colored asbestos panels add much-needed visual contrast.

The home has remained remarkably true to its initial design and, at the time of a 2015 article, had retained many of its original furnishings, including living and dining furniture designed or specified by Breuer, the original kitchen cabinets, and a built-in bookcase in the living room.

As of 2015, the interior still included the original cedar plank ceilings and walnut flooring, and the owners had restored the original orange, blue, and gold interior color scheme.5

The Snower house was built as a country residence, but is now surrounded by a sprawling maze of cookie-cutter homes. The structure spends most of the year concealed by trees, and with its cantilevered design, it almost appears to float among the greenery.

It’s a home that takes a certain amount of architectural knowledge to appreciate: while groundbreaking when it was constructed, today an uninformed observer could easily misjudge it as a holdover from a high-end trailer park.

Twelve years after the Snower house was built, Breuer’s design for the Whitney Museum of Art was completed at 945 Madison Avenue in New York’s Upper East Side.

Anyone unfamiliar with Breuer’s work would never guess the two projects were by the same architect, but look closely, and you’ll note that both buildings give the same suggestion of floating, and both show the same attention to form and materials.

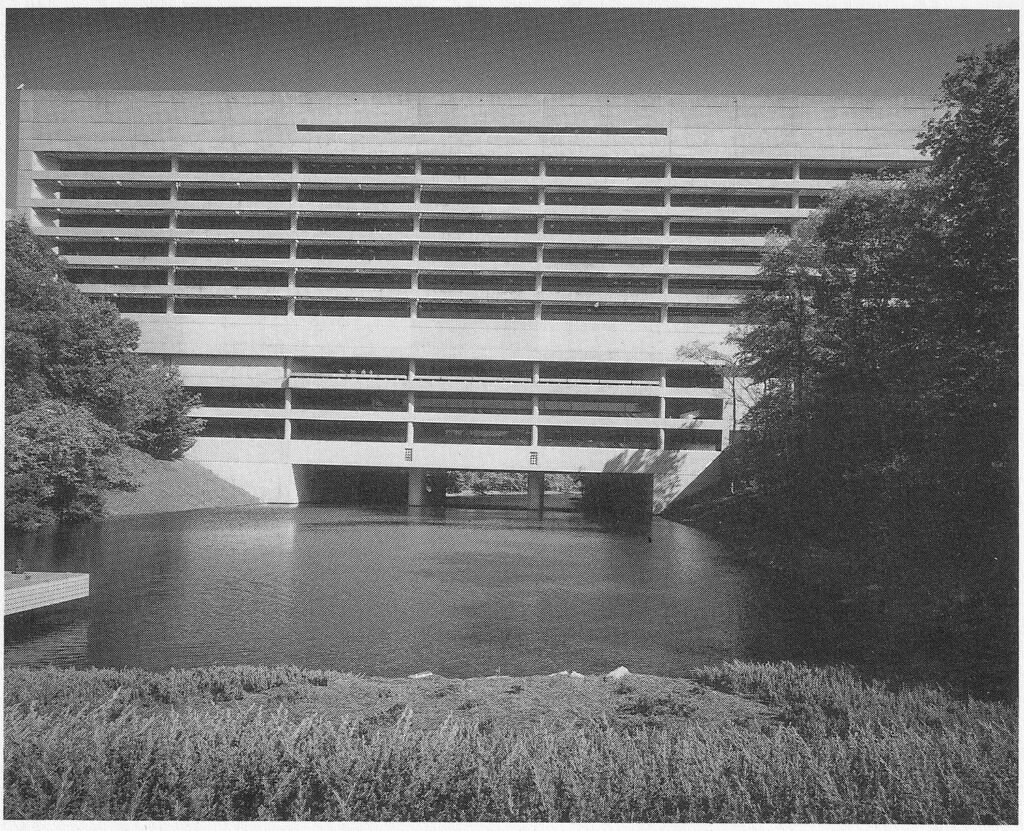

Looking something like an inverted ziggurat, the 7-story, 76,830 square foot structure — now also known as the Breuer Building — was designed by Breuer with his longtime associate Hamilton P. Smith.

The building’s exterior is defined by cantilevered floors that progressively extend toward the street, covered in dark granite tiles over reinforced concrete. The ground floor entrance is set back from the street, accessed by a bridge spanning a moat-like sunken courtyard.

The facade presents a nearly blank face to Madison Avenue, apart from a large trapezoidal window, an element that became one of Breuer’s signatures. The north side of the building facing East 75th Street is punctuated by 6 smaller windows, similar to Breuer’s use of tiny windows in the Snower residence.

The building’s interior showcases Breuer’s ability to masterfully blend textures and patterns, particularly in the lobby and stairwells.

Smooth concave dome lights in the lobby contrast against the dark ceiling and roughly textured walls, created with vertical board-formed concrete. Floors throughout the building are covered in bluestone slab tile, and the walls in the stairwells are formed with bush-hammered concrete.

Sleek bronze railing on the stairs recalls Breuer’s earlier furniture designs, and the abundance of built-in seating thoughtfully incorporated throughout the building is an obvious byproduct of his residential period.

I visited 945 Madison in January 2024, when the building was about to end its 3-year run as the temporary home of the Frick Collection.

The Frick was a grim and joyless experience, and, for whatever reason, the museum’s management prohibited photography in the galleries — it’s not like any of their boring art was worth a picture. I dodged the leering security guards and snapped a photo anyway, because fuck that Nazi-inspired nonsense.

The Frick had covered Breuer’s signature windows with giant scrims, so there wasn’t much to admire in the building’s galleries. In the image below, you can still see some of the coffered ceilings, bluestone tiles, and built-in seating.

Breuer’s creative output arguably peaked with the Whitney and became increasingly repetitive and self-referential through the late 1960s.

In 1968, the same year he was awarded the Gold Medal of the American Institute of Architects, Breuer also faced severe backlash for his proposed Grand Central Tower, which called for the demolition of New York’s landmark train station, only a few years after the destruction of the original Penn Station ignited widespread protest.

New Yorkers aren’t known for forgiveness, and at Breuer’s death, Paul Goldberger, then the architecture critic for The New York Times, stated in his obituary for Breuer that the architect was “most likely to be remembered for things that are very small — things that are not buildings at all.”6

That observation was catty but dead on, as Breuer’s contributions to architecture are essentially unknown to the public today. And why is that?

Societal taste in architecture is always fickle, but the backlash against Brutalism has been especially swift and severe. What was initially embraced in the 1960s as a universal, egalitarian, and essentially optimistic style was, by the 21st century, widely viewed as hostile, oppressive, and just plain ugly.

It doesn’t help that concrete ages poorly: it cracks, it stains, and if it isn’t regularly power-washed (and it never is) it just looks drab and dirty. Slapping white paint on old concrete buildings has become popular in recent years, but it’s a cheap trick that never succeeds.

Breuer’s output was also wildly inconsistent in the second half of his career. While he had a few outstanding gems like the Whitney, his firm also produced a large number of banal and uninspired projects in the 1960s and 70s, with a clear prioritization for commissions over creativity.

Thus, Breuer’s name is associated with such dreary designs as the Department of Housing and Urban Development (1968) in Washington, D.C., or the downright hideous building for the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (1977) in the same city.

Later projects like the Strom Thurmond Office Building and Federal Courthouse (1979) in Columbia, South Carolina, shouldn’t even be mentioned in the same breath as Breuer, since he obviously had nothing to do with their design.

Breuer’s disappearance from public consciousness is also hardly unique: most people today are unfamiliar with his contemporaries like Philip Johnson, Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, or I.M. Pei, and the average person’s assessment of any of those designers’ best works would likely be unfavorable.

Breuer is still a favorite of architectural historians and preservationists, however, and they were outraged when Breuer’s first bi-nuclear residential design was demolished in January 2022 for the construction of a tennis court.

At the same time, Breuer’s own summer home (1949) in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, was also threatened with demolition but was spared with its purchase by a local historic trust.

In June 2025, the Department of Housing and Urban Development announced the departure from its Breuer-designed facility, and the future of that complex — which lacks historic protections — is anyone’s guess.

Some of Breuer’s projects have found new uses: in 2003, part of Breuer’s landmark design for the Armstrong Rubber Company (1966) in New Haven, Connecticut, was demolished for the construction of an IKEA store, but the remaining portion of the structure has since been converted to a boutique hotel.

Atlanta’s Central Library (1980) was the last project credited to Breuer, and it too faced possible destruction until it was spared by a controversial renovation completed in 2021. That story will be forthcoming.